A Look Back At Braves Field

This article was written by Mort Bloomberg

This article was published in Braves Field essays (2015)

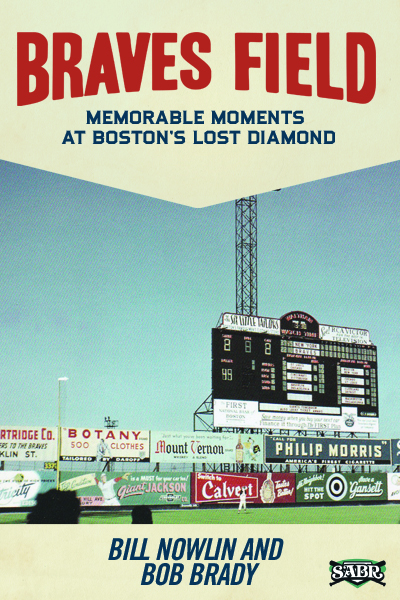

Ugly, old, barn-like, sooty, rat-infested, and the “House That Ruth Quit” are a sample of the disparaging phrases attributed to the ballyard that used to exist on Gaffney Street in Allston near the banks of the Charles River. To me, though, it was a home away from home where my childhood heroes like Bama Rowell, Earl Torgeson, Sam Jethroe, Willard Marshall, Bob Chipman, Chet Nichols, Bobby Hogue, and Johnny Logan jogged onto the field each game in the belief that they could defeat their National League rivals.

Ugly, old, barn-like, sooty, rat-infested, and the “House That Ruth Quit” are a sample of the disparaging phrases attributed to the ballyard that used to exist on Gaffney Street in Allston near the banks of the Charles River. To me, though, it was a home away from home where my childhood heroes like Bama Rowell, Earl Torgeson, Sam Jethroe, Willard Marshall, Bob Chipman, Chet Nichols, Bobby Hogue, and Johnny Logan jogged onto the field each game in the belief that they could defeat their National League rivals.

My first Wigwam trips were by car with Dad to weekend and night games (first pitch at 8:30 P.M.). Gazing to the right when we crossed the Cottage Farm Bridge (later dubbed the BU Bridge) offered a picture-perfect bird’s-eye view of the only Boston “green cathedral” I ever cared about. In the evening with arc lights beaming from its tall stanchions, Braves Field looked even more inviting. No problem parking, since the back lot of a nearby tire company on Commonwealth Avenue with which Dad did business was always open to us.

From there we walked to Hayes Bickford’s cafeteria, up the block maybe 15 minutes away at the corner of Babcock Street and a short distance from Warren Spahn’s yet-to-be-built, ill-fated diner (its grand opening was scheduled for April 1953, one month after the National League approved the Braves’ shift to Milwaukee). I always ordered their chicken pot pie, to this day the best I ever ate in a restaurant. Only my grandmother did it better … and that was minus a recipe.

Dad worked in downtown Boston, where the Braves recently had installed a ticket outlet (in Gilchrist’s department store, as I recall). Yet on most occasions he purchased our seats on the day of the game at the Gaffney Street box office. We sat frequently in the “unreserved” section (the back 10 to 12 rows) of the first-base grandstand. Priced at $1.20, these seats were easily accessible from the signature ramp that older fans may recall was built only on the right-field side of the ballpark. In the final years before the Braves left town, I would take the bus from Winthrop to Orient Heights (part of East Boston), board the MTA, and 45 minutes later arrive with friends or by myself at the special entrance to the ballpark built for trolley cars.

Having attended games from 1947 to 1952, I had the chance to view the game from several other locations. The sight lines from the reserved grandstand were poor because it was sloped so gradually that spectators in front often blocked your view, particularly if they wore hats (still popular in the post-WWII era). Fans in the 2,000-seat Jury Box next to the right-field foul pole adopted Tommy Holmes and a love affair soon was born. Throughout each game, win or lose, Tommy could be heard chirping in his high-pitched Brooklyn accent with his many devoted admirers. When Willard Marshall, known for his rocket arm, joined the Braves as part of the deal that sent Eddie Stanky and Al Dark to the New York Giants, Billy Southworth placed him in right field. Not for long, though. Holmes’s fans became so indignant that soon thereafter Tommy received a hero’s welcome home as he went back to right and Marshall became the new left fielder.

Kids attending a Saturday morning baseball quiz program hosted by Jerry O’Leary on WHDH radio were eligible for free Braves tickets in the third-base pavilion. There were wood bench seats there, and an oversized (for 1948) electric scoreboard which from that angle was difficult to see and on a sunny day impossible to decipher. On the other hand, those fans were up-close and might get to interact with coach Bob Keely and members of the Braves bullpen, which was situated down the left-field foul line out in the open directly in front of the pavilion.

The best gift I ever received from my parents was tickets to 12 games of my choice for the 1951 season. The seats they gave me were called field boxes, but in truth were below ground level just beyond the visiting team’s dugout, on the first-base side. Comparable seats were available on the opposite side of the field. But given that first baseman Earl Torgeson was one of my favorites and that in the course of a typical game more action occurs on the right side of the diamond, my preferred location was an easy pick. More good news: first row! Feeling a bit like a surfer who encounters the perfect wave, I decided to cram as many doubleheaders as possible into my game selection. One memorable twin bill in early May was against the Pirates. In the opener Warren Spahn blanked the Bucs, 6-0, for his second straight shutout. But what made the day historic was journeyman Cliff Chambers’ no-hitter in the nightcap. As Roy Hartsfield, Sid Gordon, Walker Cooper, Luis Olmo, and others came to the plate in the late innings, my prayers for a base hit grew. At the same time, an odd situation was evolving in the stands. Many of the 15,492 fans in attendance rooted for Chambers to make history. To me, that was nearly as blasphemous as cheering for Boston’s other team. Four footnotes on the game: It was the final no-hitter hurled at Braves Field; Chambers surrendered eight bases on balls; Braves starter George Estock took the loss in his big-league debut and that would turn out to be his only pitching decision in the majors; and — finally — three Braves went to the Pirates clubhouse after the game to offer their congratulations: Vern Bickford (a no-hit author himself in 1950), ex-Pirate star Bob Elliott, and future Pirate for two games Sam Jethroe.

In its finest hour, Braves Field’s public address system was adequate at best. It would not surprise me, nevertheless, if big John Kiley’s organ renditions of the national anthem were audible in Kenmore Square, especially after the Braves introduced a new state-of-the-art organ in 1950. Braves rallies were his cue to play the “Mexican Hat Dance,” which began with a soft, slow beat, increasing gradually in volume and tempo. But for good humor or earaches or both, nothing matched the serenades of the Three Troubadours. Banned as persona non grata at Yawkey’s Yard because their musical comedy routines did not fit the Fenway philosophy, they were a smash hit at every Braves Field performance. Even its mediocre PA system could not repress this slightly madcap trio. My favorite was their chorus of Hawaiian belly dance music when Marv “Twitch” Rickert came to the plate on account of his wiggle as the pitcher got ready to deliver the next pitch.

Since our pregame cafeteria stop guaranteed that trips to Braves Field’s concession stands were infrequent, there’s nothing firsthand I can say about the ballpark food or merchandise. Thanks, though, to a 1952 scorecard, here is a price list of items that were then available: hot dog, 25¢; hamburger, 25¢; egg salad sandwich, 25¢; hot pastrami sandwich, 50¢; orange drink, 10¢; beer, 35¢; peanuts, 10¢; ice cream, 15¢; pencil, 10¢; minibat, 40¢; pennant, 50¢; hat, $1.00; uniform, $6.00; and warmup jacket, $7.00.

In a related vein, Tommie Ferguson, one of the team’s batboys in the postwar era, gave me this tidbit about clubhouse manager Shorty Young. Between games of a doubleheader he would go to the stand and purchase for 30 cents apiece ham and cheese sandwiches for the Braves players. Catered postgame spreads in the clubhouse were a long way off in the future. And finally, many fans are aware that the Braves were the first team to sell fried clams. Did you know they were also the first team to remove this tasty treat from the menu when complaints were made by those in nearby seats that the frying process diverted their attention from the game? So in 1949 the suddenly unpopular clams were replaced by baked beans. This item also was a temporary addition to food sold at the Wigwam since it did not appear on the aforementioned 1952 menu (probably because it, too, carried unwelcome side effects!).

Last among the Wigwam’s deficiencies was an eyesore as well as a potential health hazard: smoke bellowing from Boston & Albany steam engines behind the left- and center-field fence. Nonetheless, I really loved the place the Braves called home until the transfer of the franchise to Milwaukee, and in my heart it will always remain a shrine. As it approaches its centennial, Braves Field is the last major-league baseball facility built in Boston. Guaranteed it will not receive the accolades or attract the pomp and circumstance that marked the 100th anniversary of the ballpark their former American League neighbors own. Yet the Home of the Braves for 38 colorful seasons occupies a unique role in the history of our sport that hopefully will be recognized and celebrated for generations to come.

MORT BLOOMBERG is a retired psychology professor with a lifelong magnetic attraction to the Boston Braves. He does not often write, but nowadays when he does … Mort’s subject matter spotlights the post-WWII inhabitants of Braves Field.