A Man of Many Faucets, All Running at Once: Books by and about Branch Rickey

This article was written by Leverett T. Smith Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 28, 2008)

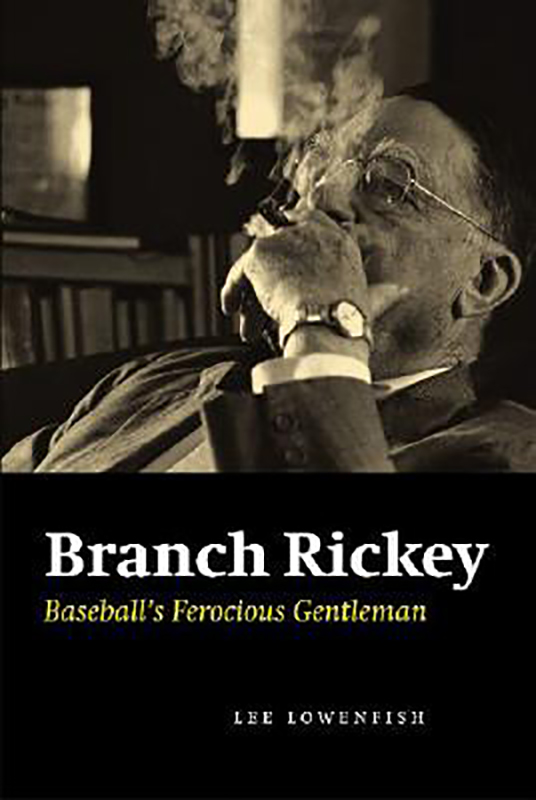

- Lee Lowenfish. Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. 683 pp. Notes, bibliography, index, photographs.

- Branch Rickey. Branch Rickey’s Little Blue Book. Edited by John J. Monteleone. Preface by Stan Musial. New York: Macmillan, 1995. 142 pp. Index.

- Murray Polner. Branch Rickey: A Biography. Revised Edition. Foreword by Branch B. Rickey. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2007. 274 pp. Bibliographic note, index, photographs.

- Andrew O’Toole. Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh: Baseball’s Trailblazing General Manager for the Pirates, 1950–1955. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000. 213 pp. Notes, index, photographs.

- Branch Rickey, with Robert Riger. The American Diamond: A Documentary of the Game of Baseball. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965. 204 pp. Photographs and drawings by Robert Riger.

- Arthur Mann. Branch Rickey: American in Action. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1957. 312 pp. Photographs.

Lee Lowenfish’s recent Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman establishes itself as the place where future studies of Branch Rickey can begin.

Lee Lowenfish’s recent Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman establishes itself as the place where future studies of Branch Rickey can begin.

With backgrounds in both journalism and academic history, Lowenfish has produced a thoroughly researched, extensively documented, and clearly written version of Rickey’s life, equally valuable for the general reader and the serious researcher. It clearly establishes the Mahatma as a major figure in baseball in the first three quarters of the twentieth century. It’s not surprising to learn that Lowenfish’s Rickey has won the Seymour Medal for 2008. Branch Rickeylived a life as busy as it was long.

Lowenfish focuses his account on “the man who had revolutionized [baseball] not once but three times” (1). These are the development of the farm system while he worked in St. Louis, the reintegration of baseball while in Brooklyn, and the expansion of baseball, which he helped inspire as president of the Continental League. As extraordinary as these changes are in themselves, Lowenfish keeps his focus—and the reader’s interest— on the man involved in making them.

The reader gets a full account of Rickey’s family heritage, youth, and education in rural Ohio, his involvement in college athletics, his own playing career, and his work for the St. Louis Browns. After his stints with the Cardinals and Dodgers, there are also accounts of Rickey’s difficult years in Pittsburgh and his last “senior consultant” position with the August Busch–owned Cardinals in the early 1960s. An executive, Rickey was in an owner’s role only in Brooklyn, and even there has had other owners to answer to. In effect, he was fired from all these positions—by Sam Breadon in St. Louis, by John Galbreath in Pittsburgh, and he was eased out by Walter O’Malley in Brooklyn. Lowenfish wonders if this isn’t one reason for his neglect by baseball historians (although one might argue and ask which baseball executive has been written about more).

Lowenfish does this in an inspired prologue, in the first half of which he describes Rickey’s last speech and his funeral. In the second half, he explains the nature of Rickey’s character and why historians don’t give him more notice. For Lowenfish, “it is past time to bring him back to life in the fullness of his passions and his intellect” (8). He concludes by characterizing Rickey as “a man of astounding energy and radical individualism, a most unusual conservative revolutionary” (9). In his prologue he focuses not on the three revolutions but on who Rickey is: his oratorical style, his busyness (Lowenfish calls it his “remorseless Protestant ethic to resist idleness” [6]), his collegiality, his loyalty, his respect for physical and spiritual courage, his Christian faith, his concern for social justice, his belief in the American capitalist system, his “genuine warmth, humor, and compassion” (9), and his love of family.

A member of what Lowenfish calls “the conservative inner sanctum of baseball’s managerial elite” (453), Rickey was, in fact, a conservative businessman, and a remarkable one at that. Yes, he valued home, family, church, and country above all else. Lowenfish speaks of his “faith in God, family, and baseball,” the last being an embodiment of national values (299). This included, in the postwar years, a cold-war anticommunism that enabled him to find some good even in Senator Joseph McCarthy’s excesses. As Lowenfish reports, Rickey felt McCarthy had “a good fastball, but no control” (518). In these beliefs, he was not unlike most baseball executives. What made Rickey unusual was his readiness to acknowledge other points of view and to encourage them if they could help him achieve his goals. Consider some of his protégés: executive Larry MacPhail, manager Leo Durocher, player Jay “Dizzy” Dean.

And consider the reserve clause, the cornerstone of baseball during Rickey’s lifetime. Lowenfish deals with the reserve clause in the player contract only briefly, but tellingly. As a member of baseball’s establishment, Rickey could be expected to regard it as essential to the game. Lowenfish describes him as “always consistent about the need for a reserve clause in any kind of professional baseball” (367). But as president of the Continental League, Rickey had to do something to relax the reserve system so that the league’s clubs would have access to players (555). He also used the threat of congressional action in his negotiations with Major League Baseball, despite his Republican wariness of government interven- tion in business (568). Finally, he supported the bill proposed by Estes Kefauver (eventually voted down) that would limit to one hundred the number of players reserved by any one club (568).

Rickey had never been inflexible about the reserve clause, it turns out. As Lowenfish reminds us, Rickey “had made individual exceptions in the past in the case of such star players as George Sisler and Rogers Hornsby” even though “he had been . . . uncompromising in defense of the strict restrictions on virtually every other player” (547). This, it seems to me, is what fascinates Lowenfish about Rickey: He is a conservative willing to be an innovator.

There are ten chapters on his St. Louis years, Rickey commenting on his ambition there: “I must make a great ball club,successful artistically and financially in a town where there is every handicap under the sun against my making good” (128). The material in the nine chapters on his Brooklyn years is more familiar material but examined from a different perspective. One motif that runs throughout the book but is most prominent here is Rickey’s language, his manner of speaking, and its effect on the press. A Brooklyn fan once remarked, memorably, that “he is a man of many faucets, all running at once” (324). Lowenfish speaks of Rickey’s “inevitable circumlocutions of speech” (319), adding that his grudges against sportswriters were “his least attractive character quirk” (400).

Rickey and Jackie Robinson were certainly two of a kind, “ferocious gentlemen” to be sure, but perhaps Leo Durocher and Rickey were the oddest couple of them all. Rickey felt Durocher “had the right kind of competitive smarts and leadership skills” (240). They shared, as Rickey said of Durocher, “a great will to win.” Their differences were stark.

As for Leo’s aggressive, almost delinquent behavior off the field, Rickey was used to dealing with such types from his earliest days as a country schoolteacher. It probably wasn’t a shock to him when he learned that Durocher had been expelled from high school for punching a mathematics teacher. Rickey was always confident that he could reason, inspire, and straighten out the way-ward member of any flock. (228)

Alas, Rickey’s plans for Durocher to be Jackie Robinson’s manager went awry when Durocher was suspended for Robinson’s rookie season. Worse, when Durocher returned the following year, Robinson was out of shape: “He was thin for Shotton, but he’s fat for me,” as Durocher put it. The animosity between him and Robinson became a feature of the great Giant–Dodger rivalry in the fifties after Durocher moved from Ebbets Field to the Polo Grounds.

Lowenfish keeps Rickey’s life beyond baseball in focus. His politics were enthusiastically Republican: “Herbert Hoover. possessed, in Branch Rickey’s opinion, the finest attributes of an American leader, a man who combined belief in capitalist enterprise with a genuine sense of social service” (188). An anticommunist and cold warrior, Rickey was in the audience when Winston Churchill gave his famous “Iron Curtain” speech (390). Finally, it is the sheer frenetic energy with which Rickey approached life that impresses the reader:

When he wasn’t visiting family, scouting farm teams and young prospects, speaking to church groups, or drumming up support for Republican candidates for office, Branch Rickey made time for an annual postseason duck hunting expedition with friends in rural Missouri and Illinois.(290)

So large a study of so large a man still must leave some things out, and this reader missed any treatment of Rickey’s relationship with Dodger statistician Allan Roth, who is mentioned only twice. The first time it is in an aside to a description of the statistical work that Travis Hoke, a young St. Louis reporter, did for the Browns. The second time is an acknowledgment that Roth helped Rickey prepare a Life magazine article that appeared under Rickey’s name in 1954 (74, 527). It’s odd that there’s nothing about Roth’s years with the Dodgers. There are the inevitable few errors, typographical and otherwise. My own favorite is the imputation that John Mize of the Giants led the league in home runs in 1942; it was Mel Ott who led, with 30, the Big Cat and Dolph Camilli tying for second place, with 26.

Lowenfish provides extensive documentation. I miss only an introductory description of the nature and location of unpublished papers, interviews, and other materials. Though much of this information is available in his acknowledgments, it might have been better to present it more formally here. Even so, Lowenfish’s endnotes and bibliography will be the best place to begin a study of Rickey from now on, at least until new information about the man is discovered. I learned about several earlier books involving Rickey as subject or author and was enthusiastic about going on to read them.

Arthur Mann’s Branch Rickey: American in Action appeared in 1957, and his relation to Rickey and Rickey’s involvement in the book make it interesting reading still. According to Lowenfish, Rickey felt Mann was no biographer and never read the book (Lowenfish 593). On the other hand, having served as a kind of personal secretary to Rickey, Mann presumably had privileged information, and it’s clear that Rickey had extensive input into the book. In addition to being its subject, the Rickey of 1957 is often invoked in such phrases as “Rickey said in describing” or “Rickey laughed inrecollection” or Rickey “calling the occasion to memory” (60, 108, 123). It’s almost as if Mann wanted his narrative to be as close to an autobiography as possible.

Two things seem especially interesting about Mann’s portrait. The first is Rickey’s language and its relation to his character. Mann acknowledges the many negative assessments of Rickey, particularly in the press. There are complaints about his “evasive phraseology” (132). He was considered a bad manager because he “talked over his players’ heads, was too theoretical” (78). In Brooklyn, fans

picked up derisive nicknames for Rickey from the press—“Mahatma” and “Deacon” and “hard shelled Methodist” . . . Rickey was called the “Old Woman in the Shoe” and a violator of child labor laws. When he tried to explain [his trading Dolph Camilli, his] . . . erudite explanations were dismissed as double talk and his office was called “The Cave of the Winds.” (228)

Out of material such as this, Bernard Malamud was to fashion the villainous Judge Goodwill Banner in his 1952 novel The Natural.

Mann wants us to understand all this differently. At the outset, he tells readers about “the simplicity of Rickey’s nature” (4) and then, on the next page, that “there have been many times over the years when Branch Rickey preferred not to be understood.” This is quite a picture. Something of it emerges in Lowenfish too. The tension between these conflicting qualities is something. Mann returns to late in the book, in a paragraph about Rickey’s decision to sign African American players. Interpretations of his motivation vary. Mann contends that

most of them fall short, because they are based on the assumption that his nature and thinking are deep and complex. Actually his erudition and easy command of a polysyllabic vocabulary cloak thinking that is, more often than not, simple and basic. (215)

This version of Rickey is directly related to Mann’s treatment of Rickey’s relations with the press. He met with incomprehension in St. Louis (66, 132), and in New York his efforts to win reporters over were largely useless (126). We get a detailed report of Rickey’s public encounter with Dick Young in 1948 (129–32). Mann is somewhat less forthcoming about Joe Williams’s accusation in 1946 that Rickey didn’t want the Dodgers to win the pennant and about Rickey’s relationship with columnist Jimmy Powers (238–39).

But there is no mistaking whose side Mann is on. In many ways the book is a defense of Rickey against his detractors. Mann covers thoroughly Rickey’s years in St. Louis and the development of the farm system, an innovation that, in Rickey’s mind, had its genesis in 1913, when he worked for Browns’ owner Robert Hedges (63). Mann’s account of the Brooklyn Dodger years takes on added importance when the reader bears in mind that Mann was there and an active participant in the introduction of Jackie Robinson into Organized Baseball. That Rickey’s tenure in Pittsburgh is reviewed only briefly may be understandable in a book intended to bring out his virtues and achievements.

*****

The only book by Rickey that appeared in his lifetime, The American Diamond, was published in 1965, the year of his death. Lowenfish remarks that Rickey, ever the man of action, “hated to write.” The American Diamond is autobiographical in an unusual way—much of it is devoted to “homage to the baseball people whose life and work he had shared,” as Lowenfish puts it (593, 594). In the introduction, Rickey explains his reason for writing:

I had good intentions about writing two or three books when I received a book called The Pros one day from a stranger. It was on pro football—and magnificent. I spent several days studying this work and realized it was a powerful piece of propaganda on football. (3)

What Rickey means but doesn’t say is that The American Diamond is to be a powerful piece of propaganda on baseball.

It’s a large, coffee-table-size book, and much of it consists of Rickey’s comments on Robert Riger’s photographs. But his involvement in the book is much more than that. The first part of the book is “Immortals,” “the sixteen men who have made the most significant contributions to the game over the years.” Here Rickey’s writing is primary, while Robert Riger’s drawings are secondary, illustrative.

Seven of the immortals are players: Honus Wagner, George Sisler, Christy Mathewson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Jackie Robinson. Two more played but were chosen more for their managerial careers: John McGraw and Connie Mack. Four are executives: Charles Comiskey, Ban Johnson, Judge Landis, and Ed Barrow (though Comiskey, like McGraw and Mack, played and managed as well). Two journalists, Henry Chadwick and Taylor Spink, make the cut. The “number one immortal” is Alexander Cartwright.

In the second part of the book, “The Game,” Rickey’s words take a back seat to Riger’s images, although Rickey’s fingerprints can be found in the emphasis (in 1965!) on the Brooklyn Dodgers. In “The Game,” Riger’s photographs start with youth and neighborhood baseball and work their way up to the professional game and then through the professional season from spring training to the World Series. Occasionally there are sections without pictures, as in “Courage,” which reads like the text of a Rickey talk. In the section on Brooklyn, Rickey writes, “My eight years in Brooklyn gave me a new vision of America, or rather America gave me a new vision of a part of itself, Brooklyn.” He goes on to add that “it was a crime against a community of 3,000,000 people to move the Dodgers” (166)—a sentiment that may have been genuine, although in his manner of expressing it the reader may hear echoes of the longstanding animosity between him and Walter O’Malley.

Rickey runs through the Dodgers’ starting lineup in the 1955 World Series, commenting on each player. His discussion of Snider, Hodges, and Campanella includes an argument that runs batted in is not a significant measure of a player’s value.“Reverse the [fifth and sixth batters] in the hitting order and you will frequently reverse their RBI total” (173). Elsewhere, he offers that the hit-and-run play is “much overused” (43).

In Rickey’s essay on courage, we get a brief glimpse of a youthful Enos Slaughter. Rickey had made the point that “sometimes it is a great quality in men to show modesty even to the point of timidity or apparent lack of courage” (96). His illustration is that “Enos Slaughter was afraid to say his name.” Slaughter, as everyone who has encountered him knows, got over this. His assessment of Rickey, comprising equal parts anger and admiration, is reported in Murray Polner’s biography of Rickey: “He noticed everything, that son of a gun” (Polner 92). In my experience, Slaughter was not always so pithy. In the mid-1970s, he appeared in a class in baseball history I was team-teaching with a member of the history department—his daughter was attending our college at the time—and talked nonstop, far beyond the 90-minute class period. We were all in thrall. Nobody dared leave.

Finally, Riger’s photographs step aside for Rickey’s meditations in the section titled “The Future of the Game.” He saw three problems that needed to be solved. He hoped for something that we now call “parity” and that many of us despair of achieving. Remember that, while Rickey was writing this in. 1965, the players were busy hiring Marvin Miller, a move that would eventuate in player salaries (and owner profits) beyond even Rickey’s powers of imagination.

He understood the inevitability of expansion, although it has proceeded along lines he deplored in 1965, the motive being “notone of nationalization but of prospective profits at the gate” (202).

Rickey saw television as a threat and hoped for a screen that would be friendlier to baseball.

More than once, he mentions his fear that professional football would surpass baseball in popularity. In the four decades since the book was published, all professional team sports have mushroomed and grown into gigantic industries, greatly blunting any tendency on the part of baseball people to look over their shoulder at the NFL or any other league. The American Diamond, Lowenfish reports, is “long out of print and,” he comments, “worthy of republication” (594). He is right.

*****

Branch Rickey’s Little Blue Book is a collection of Rickey’s writings and sayings edited by John J. Monteleone “from private and public writings,” as we read on the title page. Monteleone went to the Rickey archives at the Library of Congress and found a treasure, which he lists:

131 containers of Mr. Rickey’s writing, correspondence, and speeches employment contracts, award certificates, and receipts (along with fabric swatches) from his personal tailor scores of scouting reports on every conceivable level of players, from future hall of famers to anonymous bushers; hundreds of lectures on how to play, how to scout and judge talent, and more; scores of speeches on pressing political and social issues of the day; dozens of comments on character traits that yield success, and many memos, notes and articles on legal, administrative and business issues of baseball. (xv)

From such a treasure, Monteleone has organized his sampling into nine sections, with Rickey’s scouting reports “sprinkled. throughout.” They deal with character; luck; various baseball subjects, concluding with a section on Jackie Robinson; “musings on various subjects”; Rickey’s spirituality, and finally, others’ remembrances. Monteleone has compiled and organized the quotations masterfully. This reader especially enjoyed the assemblage of Rickey’s comments on pitching (25–38), which begin with this:

In pitching we want to produce delusions, practice deceptions, make a man misjudge. We fool him—that’s the purpose of the game. The ethics of the game of base- ball would be violated if man did not practice to become proficient in deception. (25)

That last sentence in particular has the sound of Rickey. According to Rickey, New York Giants’ pitcher Carl Hubbell “produced perfect deception. He was a ‘change of speed’ pitcher who continually presented the problem of timing to the batsman” (27).

A pitcher who appears and reappears throughout the book is Dizzy Dean, one of Rickey’s favorite players. He shows up twice in the section on pitching, first as the sort of pitcher who has “the ability to see another pitcher throw a certain pitch and go right out and duplicate it to his own benefit” (26). A few pages later he’s being lauded as a pitcher who was unbeatable in his prime: “About all the scoring off Dizzy Dean in his heyday was due to his jocularity, his carelessness, his momentary indifference, his knowing he ‘had ’em beat’” (36).

Rickey rated Dean’s character high, as high as he rated Ty Cobb’s desire to excel. “Dizzy Dean . . . never saw a man throwing a ball that he didn’t have an uncontrollable yen to do it, and beat him at it” (3). Later in the book, we get glimpses of Dean and Rickey together, surely an odd association. Monteleone cites this Rickey meditation:

I completed college in three years. I was in the top ten percent of my class in law school. I’m a Doctor of Jurisprudence. I am an honorary Doctor of Law. Tell me why I spent four mortal hours today conversing with a person named Dizzy Dean. (105)

These conversations must have been something. Monteleone describes one as follows: He imagined Dean, “his huge feet on the boss’s desk, lean[ing] back and talk[ing] country style.” After their conversation, Rickey had to meet the press in an unusually disheveled condition. “‘By Judas Priest,’ he began. ‘By Judas Priest! If there were more like him in baseball, just one, as God is my judge, I’d get out of the game’” (117).

This little blue book leaves us with a picture of a very large man. I found myself, because I especially enjoy hearing Rickey’s voice, wanting a section on obfuscation, in which there would be some examples of Rickey’s purposeful unintelligibility. Perhaps the best comment on this aspect of his language comes, once again, from Enos Slaughter, who remarked that “I didn’t know what he was talking about half the time, but it sure sounded beautiful” (126). And we do get some negative comments about Rickey along the way, especially about his parsimony.

*****

The original edition of Murray Polner’s Branch Rickey: A Biography was published by Atheneum in 1982. A glance through both editions suggests that little of the text was revised for the 2007 edition. There is some re-paragraphing, and divisions within. chapters are sometimes retained, sometimes not. There is a new foreword by Rickey’s grandson Branch B. Rickey and a brief preface to the revised edition by Polner. Some forty-two titles have been added to the bibliographic note, including not only Arthur Mann’s 1957 Branch Rickey: American in Action (surely its omission in the 1982 edition was inadvertent, given Polner’s citation there of “material [Polner] did not include in his [Rickey]”) but also Lowenfish’s Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman. The photo gallery in the 1982 edition has been dropped and replaced by a new set of photos scattered through the text.

Polner says in his preface to the 1982 edition that he saw Rickey as “a genuine American hero the son of poor, rural southern Ohio farmers, who taught the worth of an ethical and moral way of life grounded in religious faith” (7). In the preface to the revised edition, he’s more specific. “One of the larger questions I wanted to know was why a conservative evangelical Christian could become so obsessed in fostering racial equality” (9). Polner concludes that “his religious faith was as decisive a factor as his well-known business acumen” (10). This interpretation has the effect of putting the Brooklyn Dodgers at the center of his biography of the man.

Polner cites Rickey’s “sense of adventure,” a quality seen in his leadership of college teams, and in his demonstration “of derring-do on the bases, of constantly attacking . . . opponents’ weaknesses” (60). Jackie Robinson, for example, Rickey described as “an adventurer,” “a man after my own heart” (183).

And in this light Rickey’s dealings with outfielder Gus Bell, as detailed by Andrew O’Toole, grow more intelligible. Rickey never liked Bell as a ballplayer and finally traded him to Cincinnati, where he had a fine career. Bell, as O’Toole reports, seemed bewildered.

I couldn’t seem to do anything to please Mr. Rickey. . . .The more I hustled, the more he’d get me for something. Why, he’d find things wrong with me that I never knew existed. He used to say I didn’trun in from the field fast enough at the end of an inning. Can you imagine that?” (O’Toole 81)

“He had no adventure,” Rickey said of him. In fairness to Bell, we should note that Rickey said much the same even about the young Roberto Clemente (O’Toole 135, 146).

This intense competitiveness, coupled with an equally intense piety, provoked intense responses from those who found themselves opposed to this man who believed so strongly in what he believed. As Polner sees it, journalists were alienated by Rickey’s circumlocution and aggressive rhetorical style, but the reasons for Jimmy Powers’s animus are never accounted for (90, 121–22). Polner allows Judge Landis to speak for the anti-Rickeyists. In private, Landis called him “that hypocritical preacher” and “that Protestant bastard [who’s] always masquerading with a minister’s robe” (137). In his interview with O’Toole, Tom Johnson, a member of the Pirates ownership, uses similarly intemperate language when describing Rickey, calling him “the old bastard” and lapsing into profanity to refer to his talent for evasive wordiness (O’Toole 54).

There comes a moment in Polner’s biography when he articulates the meaning of Rickey’s career, as he juxtaposes the values he finds in Rickey with those of Walter O’Malley. He compares

Rickey’s baseball—a nineteenth- and early-twentieth- century, slower, bucolic and pastoral sport, constant, tranquil, uninterrupted, a sentimental mirror of a world now gone—and O’Malley’s vision of change and technology, of jet travel, of the surge in population and hedonism, of amoral shifts of franchises lured by more and more revenue, and of the voracious appetites of television advertising. To Rickey, baseball remained a civil religion which acted out public functions organized religion was unable to perform; O’Malley’s faith rested on balance sheets and dividends (196).

Surely a good part of this vision of Rickey involves myth rather than reality, and he remains better understood as an adventurer. As Rickey sets forth on the Continental League enterprise, he wonders whether

[William A. Shea, who would eventually spearhead the formation of the New York Mets] and the committee want him to find a franchise for [New York City] or might they be interested in an utterly unorthodox approach requiring risk and courage? (232).

“A new and uncharted adventure,” a leitmotif in Rickey’s life, is what he envisioned this to be, the enterprise of forming a legitimate, lasting third league (233). (On third leagues, see the articles by Dan Levitt at page 97 and by David Mandell at page 104.)

*****

O’Toole’s Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh is a more focused book than Mann’s or Polner’s and is largely dedicated to a view of Rickey the general manager. The author relies on fewer sources than do his peers: newspapers, Rickey’s own papers, some interviews, and a few secondary sources, mainly Polner. All told, the book offers a great deal of Rickey in the first person, quoted from the newspaper sources and his papers. In addition, O’Toole includes some thirty pages of Rickey’s memos to other Pirate officials, including many player evaluations and along memo arguing for Ralph Kiner to be traded. These are fascinating.

O’Toole acknowledges “the wondrous Rickey” right away, even though Rickey’s years in Pittsburgh were disappointing for all concerned (vii). He is also quick, though, to quote part-owner Tom Johnson’s unflattering opinion—“the old phony” (15). Much of the book tells the story of the obstacles Rickey had to overcome to build a winning team in Pittsburgh. O’Toole characterizes it as “hindered from the start The conflict in Korea was taking young men from professional baseball at a rapid rate.” Moreover, and what made his job even more difficult, the Pirates“were effectively broke” (4). He devotes much of the book to detailing this sorry condition.

Rickey himself, O’Toole acknowledges, was part of the problem. He writes that Rickey “had vastly underestimated the job that awaited him. In addition to a major league roster that deservedly finished in last place, the farm system was almost totally void of talent” (35).

O’Toole argues that Rickey

was still the brilliant man that had built the dynasties in St. Louis and Brooklyn, but circumstances and times change. Few critics publicly recognized the financial constraints Rickey endured in Pittsburgh. The farm system was no longer a novelty. (156)

Rickey was no longer ahead of the curve, as he had been in St. Louis and Brooklyn. As a consequence, his time in Pittsburgh. appears a failure. In fact, his methods seem to have worked, they just took more time. The nucleus of the 1960 championship team was in place when Rickey left in 1955.

A particularly odd moment in the book stands out. O’Toole gives the arrival of the first African American and Latino players in Pittsburgh during these years a special look. His narrative strategy entails a rehearsal of Rickey’s experience in Brooklyn, and forthat he relies on Polner’s account. He goes back to Rickey’s experience with Charles “Tommy” Thomas, an African American on his Ohio Wesleyan team. O’Toole calls him “Tommy Thompson” throughout his account (117–18). It’s odd that neither the author nor anyone at McFarland caught this error.

*****

Each of these books is valuable, but Lowenfish’s Rickey is now the place to begin for anyone looking to understand—how would you describe him? The father of the farm system? The man who integrated baseball? The epithets, honorific and disparaging alike, could easily be multiplied, and they have been. What Lowenfish accomplishes is a broadening, deepening, and enrichment of the picture, and his meticulous acknowledgment of his sources enables fellow researchers to evaluate and either build on or question his judgments.

LEVERETT T. SMITH JR., a member of SABR since 1973, is author of The American Dream and the National Game (Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1975). Since the mid-1990s he has reviewed books for the Bibliography Committee Newsletter.

Parts of this review originally appeared in SABR’s Bibliography Committee Newsletter (August 2007).