A Question of Character: George Davis and the Flora Campbell Affair

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

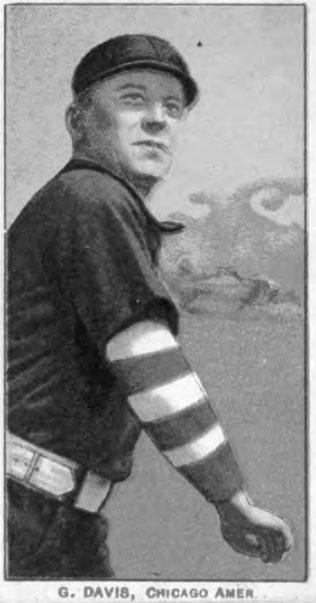

George Davis, one of the turn of the century’s finest ballplayers, remains an enigma with regards to his personal life and character. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Of the more than 300 individuals enshrined in Cooperstown, perhaps the most enigmatic is George Davis. Despite an outstanding 20-season playing career—and twice being manager of the renowned New York Giants—Davis was rarely the subject of close press scrutiny. To this day, significant aspects of his life away from the diamond remain unknown. But what is known about Davis—both good and bad—has prompted nineteenth century baseball scholar David Nemec to describe Davis as “a man of enormous character contradictions.”1

An incident that Nemec places in the Davis minus column might be called the Flora Campbell affair. On July 16, 1893, former amateur ballplayer Harrison Campbell publicly accused Davis of running off with his wife, Flora, and infant son. The accusation was a one-day local news story that Davis dismissed out-of-hand, while the national press and baseball fandom paid little heed to it. Eight years later, Campbell named Davis as co-respondent in a divorce action against Flora, citing the alleged 1893 runaway as grounds for his suit. This time, the matter drew considerable press and public attention. A furious Davis, by now ostensibly married to another woman, vigorously denied the accusation, threatening to wring Campbell’s neck if given the chance. In court, however, the proceedings were uncontested, resulting in Campbell gaining his divorce decree.

In an effort to determine whether the allegations made against Davis ring true or not, this article will examine the Flora Campbell affair, analyzing the rather fragmentary direct evidence, the circumstances surrounding both the 1893 incident and the 1901 divorce suit, and relevant aspects of the Davis persona. Integrated into this discussion will be an account of Davis’s complicated domestic situation during the 1890s. In the end, the object of this exercise will be to shed some new light on “the enormous character contradictions” of George Davis, one of turn-of-the-century baseball’s finest players.

The Flora Campbell Affair, Part I

In 1893, 22-year-old George Davis was the everyday third baseman for the New York Giants, having come to Gotham from Cleveland in a preseason trade for fading Giants icon Buck Ewing. Once in New York, the switch-hitting Davis was an immediate success. By July he was in the midst of the breakout season that would set him on the path to Cooperstown.

On Saturday, July 15, the Giants were in Cleveland, playing the final game of a three-game set against the Spiders, Davis’s old team. George was in the lineup that day and went 1-for-5 in a 7–3 Giants win. Later that date or the following morning, the club boarded the train for the return trip to New York. The Flora Campbell affair began with a brief news article buried in the back pages of the Sunday, July 16, edition of the Cleveland Plain Dealer captioned: “Harry Campbell of Erie Street Has Reason to Believe That His Wife Has Fled with a Ball Player.” The article stated that Campbell “reported to police last evening that his wife—a dashing brunette—had fled with George Davis, formerly of the Cleveland baseball club, now with the New York club. Seven years ago, Campbell was a pitcher for the Plattsville, New York club. He married Miss Florence Murray, forsook the diamond, and came to Cleveland to work as a stage carpenter. Davis at the time was a boy in Plattsville and a mascot of the club.”2

According to Campbell, “Davis knew my wife in Plattsville and they were good friends. During the visit of the [New York] club to this city, he called on her several times. At six o’clock (last) evening, I came home for my supper. My wife was very affectionate. She threw her arms around my neck, kissing me fondly and asking me what time I would be home. I replied about 11:30. I returned home at that hour and found my house stripped, my wife and baby gone, and many articles of value missing.”3 The Plain Dealer concluded the article with the discouraging observation that “the police seemed indifferent and failed to offer any assistance to the deserted man.”4

Unhappily for Harry Campbell, indifference to his plight was not confined to Cleveland’s finest. No one else was much concerned, either. As far as has been discovered, no other Cleveland newspaper re-published the Plain Dealer report, the growing prominence of former Spiders star George Davis notwithstanding. Nor was the story picked up by newspapers in New York or elsewhere. The only place the story was carried was in the July 22 issue of The Sporting News, by which time the incident had already been largely forgotten. Meanwhile, George Davis assumed his third base station for a Monday, July 17, game against Boston at the Polo Grounds and went 1-for-4 at the plate in a 4–1 New York win.

On July 19, the Plain Dealer updated its Campbell-Davis story, informing readers that Giants player- manager John Montgomery Ward had telegraphed the following: “No truth whatever in story that George Davis has eloped,” adding, curiously, that “he isn’t that kind of third baseman.”5 Davis himself had also been heard from, wiring the Plain Dealer: “Saw account in your paper. Please deny it absolutely. No truth in it.”6 By this time, the Plain Dealer may have begun to have misgivings about the Campbell allegations. Its July 19 story revealed that efforts to corroborate events had been stymied by the disappearance of the purported victim. “Campbell cannot now be found. A search for him yesterday proved futile.”7 With that, the newspaper abandoned the matter. It would not be heard of again for another eight years.

Before and After the Event

The evidence is sketchy but US Census reports suggest that Harrison Campbell was born in Illinois in April 1865. His wife, Florence, was five years younger and Canadian, born in Quebec Province in June 1870. Around 1880, she and her parents emigrated to Massachusetts. In 1886, Harrison Campbell, age 21, and Florence “Flora” Murray, age 16, were married. That same year, Flora gave birth to the couple’s first child, a son named Earl. A second boy, Harry (J. Harrison), arrived the following year. Both the Campbell children were born in Iowa, but the loss of the 1890 US Census stymies determination of whether there was also an “infant son” in the family at the time of the alleged elopement. All that can be said is Earl and Harry were the only Campbell children listed in later census reports. Another unknown is the post-Iowa whereabouts of the Campbells, until Harrison and Flora surfaced in Cleveland in 1893.

A similar shroud engulfs the early life of George Davis. Little is known except that he was born in September 1870 in Cohoes, New York, a mill town on the Hudson River wedged between Albany and Troy, and that George was the fifth of the seven Davis children surviving infancy.8 He began his known baseball career in 1886 playing for an amateur team in Troy sponsored by a local tavern owner/politico named John Durkin.9 Engagements with the Cohoes YMCA nine and other area clubs followed. In 1889, Davis was promoted to a fast Albany semipro club managed by former major leaguer Tom York. The following year, he was among the many elevated to major league ranks by the advent of the Players League, becoming the regular center fielder for the National League Cleveland Spiders.10 An offensive-defensive standout from the very beginning, Davis was an exceptionally promising and mature talent despite his being only 19 years old. Two more seasons in a Cleveland uniform then established Davis as a potential star.

Among Davis’s admirers was the newly-installed player-manager of the New York Giants, John Montgomery Ward. Shortly after assuming the helm, Ward dispatched aging Giants stalwart Buck Ewing (a longtime Ward rival) to Cleveland in exchange for George Davis. Having moved to third base in 1892, Davis became a fulltime infielder once in New York. With him and Ward anchoring the Giants inner defense, the club rose in NL standings, its crowning achievement being a postseason Temple Cup triumph over Baltimore in 1894. Following Ward’s retirement immediately thereafter, Davis, now 24, assumed the post of New York player-manager in 1895, albeit only briefly (33 games) and without much success. Remaining with the Giants after having been relieved of club command, Davis developed into baseball’s best two-way shortstop, batting .332 and fielding brilliantly during a nine-season run in New York.

Although Davis’s playing skills were widely respected, both the New York sports press and Giants fans viewed him coolly. To a certain extent, this was attributable to Davis’s amenability to doing the bidding of Giants club owner Andrew Freedman, probably the most hated figure in turn-of-the-century baseball.11 Midway through the 1900 season, Davis had been reinstalled by Freedman as Giants manager amidst public recriminations by deposed predecessor Buck Ewing that cast Davis in an unflattering light. But Davis’s persona also did him no favors. On the field, he was a clean, scientific player in a raucous baseball age who, apart from his superb play, did little to draw attention to himself.12 Consequently, reportage on Davis was usually confined to his game performance, occasionally supplemented with commentary about his up-and-down relationship with the club boss.

Off the field, Davis was colorless—a private, reserved man whom sportswriters rarely published anecdotes about or sought out for rainy-day column filler. Given that he played at the center of the baseball universe (New York, and later Chicago), perhaps the most remarkable thing about George Davis was the scarcity of press notice and fan attention accorded him during his lengthy career. Even truly heroic conduct—Davis pulled a floundering swimmer from dangerous Atlantic Ocean surf on an off-day during the 1894 season, and led the impromptu rescue that saved several women and children from a Manhattan tenement blaze in 1900—failed to generate much publicity about Davis (who did not seek it, anyway).

During the years that Davis was playing great baseball for a succession of bad New York Giants ball clubs, the Campbells remained cloaked in the anonymity of private life. In the late 1890s, however, Harrison Campbell reemerged in Akron, Ohio. There, he became active in the local Disciples of Christ congregation, eventually affecting the title of the Reverend Campbell. But by the time of the 1900 US Census, he was not listed as an Akron clergyman. Rather, Campbell was identified as a 35-year-old farmer residing in Munson, Oho, about 30 miles east of Cleveland. Interestingly, the other members of the Campbell household were recorded as his teenage son, Earl, his married sister, Cora Olmstead, his widowed mother, Susan Lafferty—and his wife, Florence Campbell, age 30.

George Davis as depicted in his days with the Chicago Americans (White Sox) on an early twentieth century baseball card. (Trading Card Database)

The Flora Campbell Affair, Part II

On the morning of March 14, 1901, the page one/top-of-the-fold headline of the New York Morning Telegram blared: “Manager George Davis Was Co-Respondent: Captain of the New York Team, Although Married, Ran Away with Wife of Harrison Campbell of Cleveland, Who Is Granted Decree.” The accompanying article related that Davis “received word from Cleveland yesterday that he has been named as co-respondent in a divorce suit that came up in the Court of Common Pleas Tuesday morning. The plaintiff is Harrison Campbell, who declared that his wife Flora had run away with the Giants leader.”13 Without mentioning that the alleged runaway had taken place eight years earlier, the Morning Telegraph continued: “Davis is married, and his wife was a constant attendant at the games played at the Polo Grounds last season.”14 The wife referred to here was Jane Holden, a native Philadelphian with whom Davis was cohabiting in upper Manhattan. “While playing with the Cleveland club,” the article concluded, “[Davis] became acquainted with Mrs. Campbell who admired the popular player. The friendship resulted in elopement of which yesterday’s divorce was the culmination.”15

Unlike 1893, this time Campbell’s allegations garnered newsprint, with various national newspapers as well as the baseball weeklies devoting space to them.16 Davis angrily denied the charges, responding in some detail. “The story from Cleveland, which alleged that I eloped with Harrison Campbell’s wife, is an outright lie from beginning to end. It is only an old story rehashed. If I had that man Campbell here I’d wring his neck. He first told this story seven years ago. It went through the newspapers and was completely thrashed out. It was a fake, and I proved this fellow not only false, but an ingrate.”17

Warming to his subject, Davis went on: “Why, I practically kept this Campbell out of the poorhouse, practically, for two years, and I never saw his wife more than half a dozen times, and then only when he sent her to me for money. His wife was a Worcester woman. [Campbell] played ball on the team at Plattsburgh, New York, once.18 She lived there at the time he married her and they moved to Cleveland. I was playing ball on the Cleveland team. This was in 1893. He got money from me on the score of his baseball connection.”19 Regarding Flora Campbell, Davis had merely played financial benefactor in her time of need. “One day [Flora] came to me. She said [Campbell] had abused her, and she asked me for money to get home to her folks at Worcester. I let her have the money, and Campbell started this little story then.”20 Finally, Davis revealed what apparently most galled him about the Campbell allegations—their likely effect on Jane. Said George: “I did not even know my wife at the time, and she has never heard this old story on which Campbell seeks to get a divorce seven years after I married.”21

By the time that Davis mounted his defense, the court of public opinion was the only forum available to him, as the Campbell v. Campbell divorce case had already been decided. Indeed, Davis apparently had not even been placed on notice of its existence until after judgment had been rendered.22 By all appearances from the limited reportage of the actual proceedings, the suit was uncontested by Flora, who probably did not even make a court appearance, much less challenge the assertions in her husband’s petition. If that was so, the proceedings before Judge Thomas Dissette would have been perfunctory and the divorce decree sought by Harrison Campbell granted almost as a matter of course.

The entry of that decree came not a moment too soon for Harry Campbell, otherwise engaged in the private courtship of Helen Usher, the teenage daughter of a Munson councilman. No sooner had the ink dried on Judge Dissette’s divorce decree than Campbell was applying for a license to marry Helen. In fact, Harry and Helen planned to be wed the very same afternoon that the divorce was granted.23 But such plans were thwarted by disapproving local officials. As somewhat gleefully reported by the Cleveland Leader, “Rev. Harry Campbell, formerly a Disciple minister of Akron, but who for the past year has been engaged in agricultural pursuits in Chardon, met with a bitter disappointment in his matrimonial intentions last evening.”24,25 Unsuccessful in obtaining a marriage license, the couple then attempted to elope only to be confronted at the door of the Usher home by the father of the would-be bride “who promptly put a stop to the proceedings.”26 At last published report, Helen was still at home while “the Reverend Mr. Campbell … [set off to] answer the call from a church in New York.”27

The Aftermath

As it turned out, Harry Campbell remained in the area, and by 1903 he was in his grave at Chardon Municipal Cemetery, dead at age 38.28 By that time, George Davis had joined the player exodus to the new American League, jumped the seemingly ironclad two-year contract that he had signed with the Chicago White Sox, returned to the New York Giants pursuant to even more lucrative contract terms, and become a major obstacle to cessation of interleague hostilities until ordered back into White Sox livery by a federal court. His domestic situation was similarly complicated.

During his bachelor days, Davis became enmeshed in another salacious scandal involving members of the opposite sex. In June 1897, the New York Journal revealed that Davis was threatened with breach of promise suits by two Manhattan boarding house residents, each of whom was under the impression that she was engaged to marry him. Other newspapers then picked up the story.29 And lest baseball fans nationwide miss news of the affair, New York Giants beat writer William F.H. Koelsch featured it in his weekly Sporting Life column, complete with embarrassing details of Davis’s correspondence with “Peaches” (young Helen Kerrison) and “Kittens” (a comely widow named Hurd).30 For the next several days, Baltimore Orioles fans serenaded Davis with cries of “Peaches” and “Kittens” whenever he came to the plate, but with little effect. Davis played with his customary proficiency and the Giants won.31 When asked to explain the situation, Davis calmly deflected press inquiries about his personal life, and the “Peaches” and “Kittens” scandal disappeared from newsprint within days—as the Flora Campbell affair would four years later.

Within a year of the fleeting “Peaches” and “Kittens” embarrassment, Davis had settled down with 25-year-old Jane Holden of Philadelphia. The two shared a Manhattan apartment, and informed 1900 US Census takers that they had married in 1898. Except they hadn’t. Indeed, they couldn’t have married—for Jane already had a husband. Rather, George Davis and Jane Holden were married on December 5, 1904, somewhere in Delaware (presumably after death, annulment, or divorce had removed the impediment to Jane’s remarriage).32 For the next 25-plus years, the couple led a quiet, almost anonymous, existence, first in New York and then St. Louis, until George’s mind began to fail in the early 1930s. Then, the Davises moved to Philadelphia to live with Jane’s older sister. Committed to Philadelphia State Hospital in 1934, George Davis remained a resident there until he died in October 1940, age 70. The immediate cause of death was paresis, the slow-moving endgame for untreated syphilis cases.33

A Question of Character

To integrate the Flora Campbell affair into an assessment of George Davis’s character, it is first necessary to determine what actually happened during this three-person drama. The task here is complicated by the fact that the accounts of two of the parties (Harrison Campbell and George Davis) are largely unworthy of belief, while the third (Flora Campbell) was never heard from.34 The problems with the Harrison Campbell account are not confined to dubious or false details like George Davis being a boyhood mascot for a team in Plattsville, a seemingly non-existent “infant son” in his elopement scenario, or Campbell’s apparent disappearance shortly after he had made his public charge against Davis and Flora. Campbell’s allegations do not square with the known whereabouts of George Davis during the crucial July 15–17, 1893, time frame—July 15: Davis played in a game in Cleveland; July 16: train ride back to New York; July 17: Davis played in game at the Polo Grounds—and the complete absence of any change in Davis’s normal routine during that period. But perhaps most telling is the 1900 US Census which puts Campbell and wife Flora under the same roof in Munson, Ohio, years after her supposed runaway.

Davis’s story is little better. The assertion that he repeatedly gave money to Harrison Campbell and “kept him out of the poorhouse, practically” merely because Campbell had once played for a baseball club in Plattsburgh, New York, is a weak one. The same goes for Davis financing an abused Flora’s return to her parents in Worcester. What does ring true is that both Harrison and Flora Campbell got money out of a young George Davis, else Davis would not have admitted same. The question, of course, is why did Davis give money to the Campbells?

At the April 2016 Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Base Ball Conference in Cooperstown, the issue was raised before a gathering of some 55 turn-of-the-century baseball enthusiasts, most of whom were fully familiar with George Davis’s sterling major league career. But few had ever heard of the Flora Campbell affair. After the facts of the matter had been presented, the attendees were asked to cast a vote on the following question: In July 1893, did George Davis and Flora Campbell leave Cleveland together for an adulterous or immoral purpose? The sharply-divided outcome—42 percent yes, 58 percent no—demonstrated that reasonable minds can disagree about events involving Davis and Flora.

In the discussion that followed, there was little division regarding one underlying component of the relationship. The assumption that Davis and Flora were having sex was treated as a given. Attendees were also near universal in their disdain of Harrison Campbell, deemed a cad, at best. Indeed, several attendees voiced the suspicion that Campbell was pimping out Flora, and not just to George Davis. Davis himself also came in for his share of censure, with the Flora Campbell affair categorized by some as nothing more than another instance of suspected—if unsubstantiated and non-specific—”deviant” sexual behavior on the part of Davis. In keeping with the spirit of the discussion, this writer then offered this thesis on the matter—unencumbered by any concrete proof but one fairly suggested by the circumstances: the affair could have been a successful-for-a-time but clumsily-concluded badger game.35 Davis, then young, single, financially comfortable, and likely horny could have been susceptible to such a scheme by the Campbells. Regrettably, the badger game construct does not explain why the scheme imploded in July 1893. Nor does it explain why Harrison Campbell resurrected the elopement story when seeking to divorce the wife that he evidently continued living with for years after the event. All that can be said is that, with the tale left unchallenged in court by either Flora Campbell or George Davis, it provided a cognizable basis for the divorce decree so urgently sought by Campbell in March 1901.

More important, what insight—if any—does the Flora Campbell affair afford us into the elusive character of George Davis? That Davis was sexually active during his twenties is hardly remarkable, although he did exhibit something of a knack for involving himself in publicly embarrassing liaisons. What is noteworthy is the short shelf-life of such incidents. Like his misadventure with “Peaches” and “Kittens,” the Flora Campbell affair had no appreciable effect on Davis’s standing with his club or the sporting public. The matter was little more than a one-day news story, and quickly forgotten. Perhaps what the affair and other indiscretions reveal most about Davis is his almost preternatural immunity to attracting public interest. Even a sex scandal or two could not keep the press or fans focused on him. For twenty big league seasons, George Davis was a greatness-taken-for-granted ballplayer whose personal life the baseball world rarely paid attention to. And that was apparently fine with Davis.

By all accounts, Davis was an intelligent, well-spoken, discreetly ambitious man who spent most of a long baseball career playing superbly in the media capitals of New York and Chicago. For Davis to have avoided press and public attention as constantly as he did bespeaks a temperament and personality of exceptionally bland proportions. Even sexcapades failed to spice up Davis in the press and public mind. In the end, the conclusion most likely to be drawn from such circumstance is this: George Davis was a private, colorless character who led an eventful, Cooperstown-bound life in spite of himself.

BILL LAMB is a retired state/county prosecutor. The life of George Davis has been a research interest of his for more than 30 years. This article is adapted from a presentation made during the Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Base Ball Conference at Cooperstown in April 2016.

Notes

1. Nemec, David, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871–1900: Volume 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 22.

2. Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 16, 1893.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. “Denies the Story,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 19, 1893.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Almost everything known about the non-baseball events of George Davis’s life has been uncovered by Walt Lipka, the former Cohoes town historian. A detailed chronology of Davis family events compiled by Lipka is contained in the George Davis file at the Hall of Fame library in Cooperstown, but even this document sheds little light on George’s youth.

9. No evidence placing Davis with a baseball team in Plattsville, New York, a vanished railroad whistle stop in Schoharie County not that far from Cooperstown, has been found by the writer. Plattsville and Cohoes were approximately 50 miles apart.

10. During its one year of existence (1890), the Players League swelled the ranks of major league players by roughly one-third.

11. Years later, it was reported that fellow players had privately nicknamed Davis “Andy” for his maintaining a relationship with the disdained Andrew Freedman. See the Des Moines Register and Leader, April 24, 1910.

12. In 20 major league seasons, Davis was ejected from a mere nine games as a player. The umpires tossed him four other times as a manager.

13. New York Morning Telegraph, March 14, 1901.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. See e.g., the Albany Times-Union, Cincinnati Post, and Cleveland Leader, March 13, 1901, and Sporting Life and The Sporting News, March 23, 1901.

17. The Sporting News, March 23, 1901.

18. Plattsburgh is located near the upstate New York border with Canada, and is approximately 200 miles north of Plattsville.

19. The Sporting News, March 23, 1901.

20. Ibid. See also, Sporting Life, March 23, 1901.

21. The Sporting News, March 23, 1901. The final comment attributed to Davis may have been garbled in the translation to newsprint, as George and Jane did not begin to hold themselves out as married until 1898. Given that, it would make more factual sense if the phrase read “several [not seven] years after I married” in the Sporting News article.

22. Although divorce case procedure varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, the co-respondent in an adultery-based divorce suit usually has no legal right to intervene in the proceedings. The right to appear and argue in court is reserved to the parties (husband and wife) affected by the suit’s outcome.

23. As reported in the Cleveland Leader, March 15, 1901, and the Denver Post, March 17, 1901.

24. Chardon was a farming town in eastern Ohio that shared a post office address with nearby Munson.

25. “The Wedding Did Not Take Place,” Cleveland Leader, March 15, 1901.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. At the time of his demise, Campbell was going by the title of the Reverend H. Lester Campbell. His mother, Susan Lafferty, lived to be almost 100 and was buried next to her son when she died in 1938. Their grave markers in Chardon Municipal Cemetery are viewable on the Find-A-Grave website.

29. See e.g., the Philadelphia Inquirer, June 22, 1897, Washington (DC) Evening Star, June 25, 1897, and Cincinnati Post, June 28, 1897.

30. See “Davis a Deceiver? The New York Shortstop Engages in Dual Courtship,” Sporting Life, June 26, 1897.

31. As per the Philadelphia Inquirer and St. Albans (Vermont) Messenger, June 22, 1897.

32. Personal information noted in Delaware marriage records viewable on-line makes the identity of the couple unmistakable. For more, see Bill Lamb, “Mr. and Mrs. George Davis: Living in Sin and Beyond,” The Inside Game, Vol. XIII, No. 3 (September 2013), 13–16.

33. There is, inarguably, something ignominious about dying from a venereal disease. But before sulfa drugs and penicillin became available, syphilis was a difficult-to-cure malady and men both high (Lord Randolph Churchill, Winston’s father) and low (Al Capone) were brought down by it. Given its often-long gestation period, Davis’s contraction of syphilis may have dated to as far back as his late-playing days. It is doubtful, however, that he got it from wife Jane who showed no signs of the disease prior to her death from a heart attack in 1948.

34. Although not conclusive regarding identity, US Census reports indicate that a likely Flora Campbell survived both her ex-husband and George Davis. In 1940, this 70-year-old Flora was living as a “widow” in a Cleveland rooming house. After that, she drops from view, her ultimate fate unknown to the writer.

35. In its classic form, a badger game is a scheme in which a woman places a man in a compromising position. The mark is thereafter extorted for money when her male accomplice, pretending to be an outraged husband, enters and threatens violence, scandal, or embarrassment.