A Slice of Piazza: A Trade Brought the Mets One of the Biggest Superstars in Franchise History

This article was written by Mike Hoenigmann

This article was published in Spring 2021 Baseball Research Journal

On August 9, 2006, the first-place New York Mets were hosting the San Diego Padres at Shea Stadium. The Mets were headed toward their first division title since 1988 and first playoff berth since 2000. It was an ordinary late summer series against an out-of-division team as the Mets held a big 13.5 game lead in the NL East.1

On August 9, 2006, the first-place New York Mets were hosting the San Diego Padres at Shea Stadium. The Mets were headed toward their first division title since 1988 and first playoff berth since 2000. It was an ordinary late summer series against an out-of-division team as the Mets held a big 13.5 game lead in the NL East.1

Yet something strange happened on that otherwise ordinary night: the Padres’ 37-year-old catcher hit two home runs off Mets ace Pedro Martinez … and was given a standing ovation both times. In fact, he took a curtain call after the first one, a rare occurrence for an opposing player in any ballpark. The reason this visiting player received such an extraordinary response and so much love from the Mets fans in attendance that night was because he was Mike Piazza, former Met and one of the biggest superstars in the history of the franchise.

Before Piazza came to New York as a superstar, he became a superstar in Los Angeles with the Dodgers. His journey to even become a big league player was nothing short of miraculous. Piazza was drafted in the 62nd round of the 1988 MLB Draft as a favor to Tommy Lasorda, a good friend of Mike’s father, Vince who grew up with him. Lasorda’s connections had been giving Piazza great opportunities well before he was drafted. Young Mike had actually celebrated with Dodgers players in their locker room after they won the 1977 National League pennant under Lasorda, who was in his first full year as manager.2 At age 16, he even had the opportunity to have the great Ted Williams watch him take batting practice in a cage in his backyard. Most importantly, his advancement from high school baseball player to professional baseball came through a series of interventions from Lasorda.

In his autobiography Long Shot, Piazza explains that although he was a great hitter in high school, he was struggling to get recruited onto a college team because he had no position defensively and had ignored his academics. It was only through Lasorda convincing University of Miami coach Ron Fraser that Piazza got an opportunity to join the collegiate team he wanted to play for.3 When he got barely any playing time as a freshman at Miami, Lasorda again stepped in and helped him transfer to Miami-Dade North, “a busy community college with an excellent baseball program” where he played his sophomore season and batted .364 as their first baseman.4

As Piazza looked into where he would play ball next (Miami-Dade was a two-year program), Lasorda had him work out as a catcher with one of his big league coaches. When he got a positive report on the workout, he called the scouting director for the Dodgers and told him, “I want you to do me a favor. I want you to draft Michael Piazza.”5 With his foot in the door and the support of Lasorda, Piazza grinded through four and a half years in the minors, including a stint as the first American in the Dodgers’ Latin American camp in the Dominican Republic, and became the organization’s top prospect before reaching the big leagues in September 1992.

With the Dodgers, Piazza became a perennial All- Star by the mid-90s, and a star both on and off the field. On the diamond, Piazza broke out in 1993 as the NL Rookie of the Year. He put up 35 home runs, a .318 batting average, an impressive 153 OPS+, and 7.0 WAR, all while playing 146 games behind the plate (149 total).6 Over the next several seasons with the Dodgers, Piazza established himself as one of the best players in baseball as well as one of its most marketable.

As a young bachelor and the best player on an iconic baseball team in one of the largest media markets in the world, opportunities began to open up for Piazza that are seldom seen for baseball players today. In his rookie season he was the only baseball player to shoot a commercial with ESPN.7 He had an endorsement with Pert Plus Shampoo and appeared in a memorable commercial for the company in 1997. But in Los Angeles, Piazza’s acting appearances usually came on TV shows. He made cameos on a number of popular shows, including Married … With Children, The Bold and the Beautiful, and a very humorous appearance on Baywatch, all during the 1994 players’ strike.

In the Baywatch episode he played himself, wearing his Dodgers hat and jersey on the beach, “practicing his swing” and eventually helping Pamela Anderson’s character rescue a woman stuck in a rip tide before walking off with her. According to Piazza, he was dating Anita Hart—the actress in the scene—at that time, which was how he got the cameo.8 During his time in Los Angeles he also dated another Baywatch actress, Debbe Dunning, known for playing the girl from Tim Allen’s show-within-a-show Tool Time on Home Improvement.

While on strike, Piazza even presented at the MTV Music Awards, struck up a friendship with Fabio, and golfed with Charles Barkley.9 Piazza’s stardom and popularity really took off during this period, when he had established himself as one of the game’s young rising stars and had some time off.

While his play would reach an even higher level in the 1996 and 1997 seasons, his relationship with the Dodgers began to deteriorate. Those two years were probably the best of his Hall of Fame career. In the 1996 All-Star Game, played in Philadelphia near where he grew up, Piazza took home the All-Star Game MVP with a performance that included a double and a massive home run to left field. He also finished in second place in the NL MVP voting in both seasons, batting .336 and .362 in 1996 and 1997 respectively.

In 1997 he led the majors in OPS+ (185) and set career highs with 40 homers and 124 RBIs (which he would match with the Mets in 1999). That 1997 season is considered among the best individual seasons of all time, and perhaps the best offensive season ever by a catcher. In fact, Piazza’s 9.0 Offensive WAR that season is the highest ever by a catcher in a single season.10 In total with the Dodgers, Piazza won five Silver Slugger Awards, earned five trips to the All-Star Game, and was clearly their best player as they headed into the 1998 season, which was the last under contract his LA contract.

In his autobiography Piazza suggests that the Dodgers felt he owed them for taking a chance on him by drafting him in the first place, and as a result, always reminded him of it and approached contract negotiations with him as if he were not deserving of the value of an All-Star player.11 The tension spilled into the media, where Piazza complained about his contract situation to Dodgers beat writer Jason Reid, and later when former Dodger Brett Butler told Bill Plaschke of the Los Angeles Times that Piazza was a “moody, self-centered ’90s player” and that although he was the greatest hitter he’d been around, a team couldn’t build around him since he wasn’t a leader.12 Piazza had also rejected contract offers from the Dodgers in the range of six years and $80 million.13

It all came to a head in mid-May 1998, when the Dodgers suddenly and shockingly traded him to the defending champion Florida Marlins. The Marlins were no ordinary defending champ, as ownership had already torn the team down, slashing payroll in advance of the sale of the team. In an iconic issue of Sports Illustrated with Piazza on the cover and the headline “Trade of the Century,” Michael Bamberger shared Piazza’s reaction to the trade: “Piazza just laughs. ‘I wish I could say it’s been a little slice of heaven.’”14 With the distrust and cloud of uncertainty surrounding Piazza and the Dodgers now gone, the next question on everyone’s mind was: where would Piazza, one of the best players in the league in the prime of his career and a pending free agent, be flipped to next?

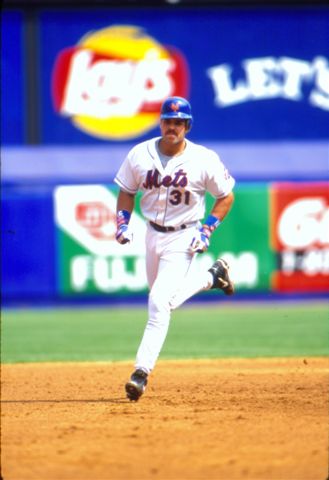

The answer to that question came just one week later when Piazza was traded to the Mets for three prospects. The date was May 22, 1998, a turning point from which the image and direction of the Mets franchise changed profoundly in the eyes of both the league and the fan base. While with the Marlins, Piazza had heard a number of teams had varying degrees of interest in trading for him, including the Orioles, Rockies, Red Sox, and the team he thought he’d ultimately be traded to, the Cubs. He was shocked when he found out it would actually be the Mets.15

Before even arriving in New York, his new teammate John Franco (who at the time was the all-time saves leader in NL history) gave up his number 31 so that Piazza could have it. That gesture gave a small insight into the magnitude of Piazza coming to the Mets and what it would mean for the franchise and fan base. At the time Franco remarked, “He’s perfect for this city. He’s young, single, a billboard kind of guy. Fifth Avenue is going to eat him up. He’ll find out that if you’re a favorite in New York, the fans will go crazy. It’s going to be like when Reggie Jackson came to the Yankees. He’s a marquee guy.”16

Franco foresaw the many marketing opportunities Piazza would have in New York and his manager, Bobby Valentine, echoed many of the same sentiments looking back at the hoopla years later when he said, “I think we got instant credibility with that trade, and we began to build an identity around Mike. The Mets had not had a player of Mike’s star quality in many years… From the first day, everything about it was rather bigger than life.”17 It was clear Piazza was a caliber of player and level of star the Mets had not had in years, and that those involved felt that impact at the time and can still feel it with the passage of time. But to turn that groundbreaking move into something more tangible, Piazza would need to perform and the Mets would need to sign him long-term.

Piazza’s 1998 season with the Mets featured plenty of ups and downs, but it set the stage for Piazza’s re-signing with the team, his unique bond with the fan base, and the continued growth of his stardom. From the start, Piazza could tell New York was different from other places he’d played. Fans were waiting at the airport to greet him and long walk-up lines formed to buy tickets to his first game.18 He delivered an RBI double in a win in his Mets debut, but he quickly found out that proving himself to New York and its fans was not going to be easy. He started to struggle to drive in runs, and with his not committing to stay with the Mets long-term, fans started to boo him.

The booing and constant questions from the media about his future began to weigh on him. It took the Mets announcing that they were postponing contract talks until after the season for him to relax and begin hitting for the last two months, changing the boos to cheers.19 For a while Piazza thought that there was little chance he would re-sign with the Mets, which would have been a disaster for them, but after receiving a curtain call following a home run against the Cardinals in August, he felt “a page had been turned.”20 He ended that 1998 season having played 109 games with the Mets, posting tremendous numbers including a line of .348/.417/.607 with 23 homers and 76 RBIs.21 While they had a late lead in the Wild Card race, the Mets ended the season one game back of the Cubs and Giants who were in a tie for the NL Wild Card. Attention quickly turned from the disappointing end to the season to whether or not the Mets and Piazza would agree to continue their relationship.

Although Piazza had felt unsure about re-signing with the Mets during the season, his feelings had begun to change. Management knew the importance of keeping him for the team to be contenders and for the image of the franchise. As Piazza explained, “The more I pondered it, the more I believed that there was a reason I’d been traded to the Mets. I didn’t really know what the reason was, but I knew I couldn’t walk away from it, just because New York was difficult. I decided that if the Mets wanted me and the contract was acceptable, I’d stay.”22

The negotiations progressed quickly during the World Series, and Piazza and his agent, Dan Lozano, agreed that not dragging it out could send a great message to everyone that he wanted to be in New York and was not interested in going anywhere else.23 The Mets signed the 30-year-old Piazza to a then-Major League record contract on October 24, 1998. The deal was for 7 years and $91 million, which beat the previous record of 6 years and $75 million the Red Sox had given to Pedro Martinez the previous offseason.24 The record contract was proof of both the Mets’ seriousness in building a winner and of Piazza’s status as one of the biggest stars (and best players) in the sport.

With the contract in hand, Piazza spent the next several years establishing himself as one of the most important players in Mets history, while also building on his superstardom that at times transcended the sport. He delivered for the Mets, being the key cog in their lineup as they made the playoffs in consecutive years for the first time in franchise history in 1999 and 2000. Opposing pitchers and managers now had a name they had to circle and plan around in the Mets lineup, one of the few players in the league at any one time who truly strikes fear into the opposition every time they step to the plate. As Piazza felt the pressure of performing under his big new contract early in 1999, he jump-started his season with a walk-off home run against Trevor Hoffman and the Padres. That launched a season that saw him match his career highs in home runs and RBIs (40 and 124) while finishing seventh in the MVP voting. The Mets clinched the NL Wild Card with a 97—66 record to make the playoffs for the first time since 1988.

The 2000 season brought even more success and dramatics centered around the Mets catcher. There was his three-run homer that capped an epic 10-run bottom of the 8th inning to come back and defeat the rival Atlanta Braves, 11—8, on June 30. There was also the season-long drama between Piazza and Yankees pitcher Roger Clemens. For Mets fans, Clemens represented the ultimate villain to their superhero Piazza, who already had great career numbers against Clemens when he hit a grand slam off him in a June game against the Yankees. A month later when they met again, Clemens beaned Piazza, knocking him out with a concussion. The pitch had clear frustration behind it, and the tension grew in the matchup of crosstown rivals.

That season Piazza led the Mets to the playoffs again, finishing third in the MVP vote after posting a .324 batting average and 113 RBIs.25 This time, Piazza and the Mets reached the World Series, the first and only time Piazza reached the Fall Classic in his career. Their opponent was the Yankees, World Series champions the past two seasons, and in three of the last four. Although the Yankees were the favorites, Piazza’s presence gave Mets fans hope. He would again clash with Roger Clemens in Game 2 at Yankee Stadium. In the top of the first inning Clemens broke Piazza’s bat with an inside fastball. The ball rolled foul and the top half of Piazza’s bat landed near the pitcher’s mound. Clemens picked it up and chucked it in the direction of Piazza, who had started running up the first base line, not knowing where exactly the ball was. This set off more drama, benches clearing and all. However, Clemens and the Yankees would get the better of Piazza and the Mets that night and in the Series, winning their third straight world championship in five games. Piazza hit two home runs while driving in four.

As great and successful as the 1999 and 2000 seasons were for Piazza and the Mets, a singular moment in 2001 became the most iconic in Piazza’s career and an indelible part of Mets and baseball history. Following the terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, sports were put on hold as the country, and New Yorkers in particular, turned their attention to the tragedy, rescue missions, and caring for survivors and all of those who were directly affected. The Mets and Yankees both gave their time and presence to help supply efforts and to meet with, talk to, and provide some sort of comfort to those who had either been first responders at the World Trade Center, or families who lost loved ones in the attack.

As baseball started up again a week later and through the end of the 2001 season, the two New York baseball teams sort of became “America’s Teams,” with fans of opposing teams giving them standing ovations and holding up signs of support. The first major sporting event held in New York following the attacks was on September 21 at Shea Stadium, a game between the Mets and their biggest rival and kryptonite, the Atlanta Braves. The night featured lots of extra security, performances by Marc Anthony, Diana Ross, and Liza Minelli, honoring of rescue workers, a 21-gun salute, a pregame exchange of hugs between the two teams, and an announced crowd of 41,235 fans who came to watch a baseball game that would hopefully be part of the healing process.26

The biggest moment of the night, however, came in the bottom of the eighth inning with Mets trailing the Braves, 2—1, Desi Relaford on first base, and Piazza stepping up to the plate. In his recap of the game in the New York Times the following day, Tyler Kepner described what transpired next: “With one strike, Piazza got a 96-mile-an-hour fastball and drilled it off the middle tier of a three- tiered camera stand in center field. He took a curtain call from the fans, lifting his helmet with one hand, kissing the fingers of the other and pointing to the crowd.”27

Reflecting back on the moment, Piazza believed they “had” to win this game and remembered how emotional he was before and during the game. He described the homer by saying, “I caught that fastball with the full force of my emotional rush. When it cleared the fence just left of center and caromed off a distant TV camera, I thought the stadium would crumble into rubble.”28

The home run has truly taken on legendary status: it is shown whenever there is a discussion on sports after 9/11 or the biggest moments of Piazza’s career. It was evidence of the power of sports to bring some joy and healing to a hurting city, and the power of Piazza to come through in the clutch—to be the team’s superstar. The home run, which gave the Mets a 3—2 lead that would be the final score, is so highly thought of that during the final season at Shea Stadium fans voted it the second greatest moment in the history of Shea, behind only the clinching of the 1986 World Series and one spot ahead of the 1969 World Series Game 5 clincher.29 With one swing of the bat, Piazza cemented his place in Mets and New York history.

New York wasn’t just a place where Piazza continued his great play and built on his legacy in baseball. It was also where he continued to grow off the field with commercials and even a cameo in a major movie. In the early 2000s, Piazza had endorsements with MCI (a long distance phone company), Callaway Golf, Nerf, and Claritin. He shot MCI commercials with other stars such as fellow athletes Emmitt Smith, Terry Bradshaw, and Hulk Hogan, country singer Toby Keith, and puppet/sitcom star ALF. Industry experts at the time estimated he pulled in around $3—10 million a year from his endorsements.30 For reference, in 2019 Bryce Harper made the most money of any MLB player in endorsements with an estimated $6.5 million, and the next highest was Mike Trout at $3 million.31 So Piazza was potentially pulling in more endorsement money almost 20 years ago than the top baseball player does now, and was definitely pulling in more than any other player in 2019 not named Bryce Harper.

That says something about how big of a superstar Piazza was, as well as how baseball is lacking true star power in America today. At the time, a Los Angeles Daily News columnist noted, “Show-business people say his blend of good looks, charm and humility make him a natural salesman.”32 Advertising executive Bob Dorfman added, “The fact is he is getting deals…You look at guys who go beyond the shoe deals and the athletic-based deals and Mike has transcended that and I would use that as a yardstick.”33 After a few seasons with the Mets, Piazza had established himself as one of the most marketable players in the game, and in some ways had transcended baseball in a way that very few modern players do.

It wasn’t just commercials that Piazza was involved in. The summer he came to New York there was a video game released for Nintendo64 named Mike Piazza’s Strike Zone. Piazza also appeared as himself in the rom-com movie Two Weeks Notice in 2002, which starred Sandra Bullock and Hugh Grant. He graced the cover of GQ in 1999 in advance of his first full season with the Mets. He appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated five separate times, twice with the Dodgers, once for the “Trade of the Century,” and another two times with the Mets.

Bobby Valentine looked at the impact of his celebrity status on the Mets this way: “I think the team needed somebody like Mike. We needed to be able to have that celebrity status because, a) we were in New York, and b) we were competing on a daily basis with a celebrity team across the borough. There was no other chance for us to compete on Page Six [the New York Post gossip section] or on talk radio without the celebrity status of Mike.”34 At a time when the Yankees were winning championships seemingly every season and baseball was in a period of national revival following the 1998 home-run-record chase, Piazza was far and away the team’s biggest star and with that brought the Mets credibility and attention.

Piazza’s play began to decline in the last few years of his contract as age and the wear-and-tear of being a catcher caught up to him, but the mark he had made on the franchise and its fans had been deeply etched. In his last game as a Met at Shea in 2005, the team played a video tribute to him during the game, manager Willie Randolph batted him cleanup for old time’s sake, and he was removed in the top of the eighth inning to get one more standing ovation.35 He played two more seasons after leaving the Mets, one with the Padres and one with the A’s.

It wasn’t long after he retired that he was back involved with the Mets and big moments. When the Mets closed Shea Stadium in 2008 and opened Citi Field in 2009, two players took center stage as the last ones off the field and first ones on the new field: Tom Seaver and Piazza. In 2016 Piazza also joined Seaver as the only Mets enshrined in Cooperstown with a Mets cap and the only players to have their numbers retired by the team. Before he had actually been inducted into the Hall, Piazza explained why he wanted to go in as a Met, saying, “Maybe I’m hypersensitive in this respect, but I appreciate appreciation. Over the years, the Mets have shown me theirs. I seldom felt that the Dodgers did.”36

The bond between Mets fans and Piazza had become as strong as any between an athlete and a fan base in sports. To Piazza, there were two main reasons: “The first was choosing to sign with the ball club after I was relentlessly booed in 1998… The second factor was 9/11. It was a shared and profound experience, the kind that people can only get through together. Everyone suffered, and grew closer for it.”37

The superstar had chosen to stay with the Mets even after the fans and media put him through the wringer in his first season with them. That commitment started the bond and the way he carried himself following the 9/11 attacks combined with his iconic home run in the first game back in New York cemented that bond. Piazza had officially transformed from a star ballplayer to a legendary one in the annals of New York sports.

Piazza’s Met career stretched from 1998 through 2005, and during that time he climbed the leaderboard in most Mets career stats. Piazza is fourth on their all-time list in Offensive WAR (30.8); third all-time in batting average (.296), home runs (220), and RBIs (655); second in OPS (.915); and first in slugging percentage (.542). His 124 RBIs in 1999 are tied for the most ever by a Met in a single season with David Wright, who matched him in 2008.38 He was also a seven-time All-Star with the Mets, making it every year but one with the team, and won five of his Silver Sluggers with them as well. All of these numbers are impressive, but they do not tell the overall impact he had on the team. Piazza’s arrival ushered in one of the most successful eras in Mets history, and he was the central factor in that success.

Piazza’s success, impact, and superstardom with the Mets puts him in rarefied air in franchise history, a place occupied by Seaver, who is without much doubt the best player in franchise history and a superstar in his own right. He won three Cy Young Awards with the Mets and most importantly, led them to their first World Series Championship in 1969. More recently, David Wright established himself as a lifelong Met, the franchise’s career leader in many categories, a fan favorite, and the team captain. He will probably see his number 5 retired next to Piazza’s 31 and Seaver’s 41, and with it join an exclusive Mets club.

When looking back over the history of the New York Mets, there have only been a few times when the team reached national prominence. Doing so is made more difficult considering that they play in the same city as possibly the most famous sports franchise in America, if not the world, the New York Yankees. At the turn of the century, the franchise made the playoffs in consecutive years for the first time, made the World Series against the Yankees, and gained significant national spotlight. It would be hard to argue that any of that could have happened had it not been for their acquisition of Piazza in May 1998.

At no other time in franchise history have they brought in a star in the prime of their career who delivered in as many ways as Piazza did. He was an All-Star on the field and one of the most recognizable and talked about athletes off of it. Piazza was simply one of the biggest superstars in Mets history.

MIKE HOENIGMANN has been a SABR member since 2020. He has his Masters Degree in History and is a social studies teacher on Long Island. Mike played baseball growing up and has been a lifelong Mets fan. He has a particular interest in the convergence of two of his favorite things: American history and baseball.

Notes

- “San Diego Padres at New York Mets Box Score, August 9, 2006,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN200608090.shtml.

- Mike Piazza and Lonnie Wheeler, Long Shot, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013, 3.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 40.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 45, 47.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 49-50.

- “Mike Piazza,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.baseballreference.com/players/p/piazzmi01.shtml.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 120.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 131.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 132.

- “Mike Piazza,” Baseball-Reference.com.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 174.

- Steven Booth, “De-constructing the Piazza trade,” The Hardball Times, December 16, 2010, accessed July 2, 2020. https://tht.fangraphs.com/de-constructing-the-piazza-trade.

- Booth.

- Michael Bamberger, “Playin’ the Dodger Blues.” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1998, accessed July 6, 2020. https://vault.si.com/vault/1998/05/25/playin-the-dodger-blues-in-the-course-of-a-few-traumaticdays-mike-piazzas-world-turned-upside-down and-si-was-there-when-he-heard-the-news-that-his-la-dayswere-over.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 185.

- George Vecsey, “Sports of The Times; Will the Numbers Work Out for Piazza as He Shifts to New York?” New York Times, May 24, 1998, accessed July 3, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/24/sports/sports-times-will-numbers-work-for-piazza-he-shifts-new-york.html.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 187.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 186.

- Jason Diamos, “BASEBALL: The Mets Agree to Make Piazza Baseball’s Richest Player; Leiter Says He Is Close to a $32 Million Deal,” New York Times, October 25, 1998, accessed July 2, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/25/sports/baseball-mets-agree-make-piazza-baseball-s-richestplayer-leiter-says-he-close.html.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 194.

- “Mike Piazza,” Baseball-Reference.com.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 195.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 197.

- Diamos.

- “Mike Piazza,” Baseball-Reference.com.

- Tyler Kepner, “BASEBALL; Mets’ Magic Heralds Homecoming,” New York Times, September 22, 2001, accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/22/sports/baseball-mets-magicheralds-homecoming.html.

- Kepner.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 247.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 342.

- Liz Mullen, “Piazza catching on as pitchman and as actor,” Sports Business Journal, October 7, 2002, accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/Journal/Issues/2002/10/07/Special-Report/Piazza-Catching-On-As-Pitchman-And-As-Actor.aspx.

- Kurt Badenhausen, “Baseball’s Highest-Paid Players 2019: Mike Trout Leads With $39 Million,” Forbes, April 1, 2019, accessed July 16, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kurtbadenhausen/2019/04/01/baseballs-highest-paid-players-2019-mike-trout-leads-with-39-million/#287db8fd6cc7.

- Matt McHale, “Piazza makes splash in commercials,” Los Angeles Daily News, August 17, 2001, accessed July 3, 2020. https://www.chron.com/sports/astros/article/Piazza-makes-splash-incommercials-2052297.php.

- Mullen.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 201.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 313.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 343.

- Piazza and Wheeler, 344.

- “New York Mets Top 10 Career Batting Leaders,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/NYM/leaders_bat.shtml.