A Surprising Disappointment: The Minnesota Twins of the Late 1960s

This article was written by Daniel R. Levitt

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the North Star State (Minnesota, 2012)

On October 14, 1965, the Minnesota Twins lost a heartbreaking World Series Game Seven to Sandy Koufax and the Los Angeles Dodgers, 2–0. While the disappointment was palpable, there was every reason to believe the Twins would soon be back in the Series. The team had won the pennant convincingly with a record of 102-60, seven games ahead of the second place White Sox. Owner Calvin Griffith, acting as his own general manager, had built a deep and talented club. And the once mighty New York Yankees dynasty that had dominated the American League over the previous four decades appeared to have run its course.

In Harmon Killebrew and Tony Oliva, the Twins had two of the top hitters in the league. Shortstop Zoilo Versalles led the league in total bases and runs scored, won a Gold Glove, and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. Along with Versalles, among the team’s position players The Sporting News named Oliva, center fielder Jimmie Hall, and catcher Earl Battey to their year-end all-star team representing the American League’s top players. Left fielder Bob Allison was only one season removed from finishing second in the league in OBP and fourth in slugging.

In Harmon Killebrew and Tony Oliva, the Twins had two of the top hitters in the league. Shortstop Zoilo Versalles led the league in total bases and runs scored, won a Gold Glove, and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. Along with Versalles, among the team’s position players The Sporting News named Oliva, center fielder Jimmie Hall, and catcher Earl Battey to their year-end all-star team representing the American League’s top players. Left fielder Bob Allison was only one season removed from finishing second in the league in OBP and fourth in slugging.

Led by these and other stars, the team dominated the league’s scoring with 774 runs; Detroit finished a distant second with 680. In 1963 and 1964 the team had hit 225 and 221 home runs respectively, the second and third highest single-season totals of all time up to that point. In 1965 manager Sam Mele chose to emphasize the team’s speed and the club stole 92 bases—fourth in the league—while being caught only 33 times. The Twins featured a terrific blend of power and speed.

The team also sported an excellent and deep pitching staff. Minnesota finished third in the league in ERA despite pitching in one of the league’s better hitters’ parks. Six pitchers started at least nine games, and every one could boast an ERA below the league average. Between 1963 and 1970 each of the six would win twenty games in a season at least once.

With 283 lifetime wins, then-rotation anchor Jim Kaat is currently on the Hall of Fame ballot and would not be a poor choice if elected. One of the league’s best left-handers, in 1965 Kaat went 18–11 with a 2.83 ERA while leading the league in games started. Teammate Jim “Mudcat” Grant led the league with 21 wins and a .750 winning percentage. At that time only one Cy Young Award winner was named for the major leagues, which in 1965 went to the National League’s Sandy Koufax. The Sporting News, however, named a Pitcher of the Year for each league and awarded the American League honor to Grant.

Curveball pitcher Camilo Pascual was the third Twins pitcher with over 20 starts in 1965. He led the league in strikeouts from 1961 to 1963, finished second in 1964, and won at least twenty games in both 1962 and 1963. Unfortunately, after a great start to the 1965 season that included winning his first eight decisions, he tore a muscle in his back near his shoulder. Pascual made it back by early September and started Game Three of the World Series. Although he pitched with less than stellar success after his return, Pascual was only 31, and the Twins had every reason to believe he would bounce back in 1966.

The other three hurlers who started at least nine games consisted of two youngsters, 20-year-old Dave Boswell and 21-year-old Jim Merritt along with swingman Jim Perry. Boswell and Merritt both turned in an ERA below the league average and struck out more than seven batters per game. Fourth starter Perry finished ninth in the league in ERA. Al Worthington, with 21 saves and a 2.13 ERA, anchored a good bullpen.

The Twins were not only talented but young. No player with over 150 at bats was yet on the wrong side of 30; of the pitchers, only Pascual was older than 30. With good reason, the Twins and their fans looked forward to a promising future.

* * *

But it was not to be. The Twins would not again win the pennant for more than 20 years, behind a completely different generation of players. The club came agonizingly close in 1967 when no dominant team emerged, and after some retooling, won division titles in 1969 and 1970. Nevertheless, with a boatload of young talent that had already proved it could win at the highest level, Minnesota averaged only 86 wins from 1966 though 1968. This was not going to win a pennant in the ten-team American League.

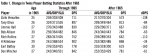

So what happened? Why did the Twins, who showed so much promise in 1965, fail to capture another flag? Like many complex questions, one can identify several causes for the failure to repeat. Most significant was the unexpected and dramatic falloff in production from the top position players. Table 1 highlights the players’ performance before and after their pennant winning season. Every single player batted worse over the remainder of his career than through 1965. And not just a little bit worse, several simply collapsed below the level of a major-league-caliber baseball player.

So what happened? Why did the Twins, who showed so much promise in 1965, fail to capture another flag? Like many complex questions, one can identify several causes for the failure to repeat. Most significant was the unexpected and dramatic falloff in production from the top position players. Table 1 highlights the players’ performance before and after their pennant winning season. Every single player batted worse over the remainder of his career than through 1965. And not just a little bit worse, several simply collapsed below the level of a major-league-caliber baseball player.

Jimmie Hall played for several years after 1965, but never again as a more than a stop-gap. Some of his decline may be attributed to a beaning, but in any case, his dramatic fall-off left the Twins with a gaping hole in center field. Catcher Earl Battey suffered from chronically sore knees, exacerbated by goiter and weight gain that likely led to a premature end to his career. But the suddenness from which he fell from one of the league’s top catchers to out of the league in just two years would surprise almost any organization. Third baseman Rich Rollins had regressed since breaking in as a regular in 1962, when he actually led all American League players in votes for the All-Star game. The next year he hit .307 to finish third in the batting race, and in 1964 he led the league in triples. Nevertheless, despite his still young age, after 1965 Rollins would never again be a quality major league regular. In 1966 Bob Allison suffered a broken bone in his hand and turned in only two more quality seasons. Tony Oliva’s recurring problems with his right knee and a shoulder separation in 1968 left him a star but well below the level he had established during his first two years as a regular.

Zoilo Versalles, though, may have been the saddest case of all. Uncovered by legendary scout Joe Cambria, in the summer of 1957 Versalles arrived in Key West as a 17-year-old: hopeful, scared, unable to communicate in English, and thrown into a segregated society he didn’t understand. Versalles covered much of his anxiety with a cocky swagger and a reputation as a hot dog. The talented youngster quickly worked his way through the Twins system and by 1961 was the team’s regular shortstop as 21-year-old.

After his 1965 MVP season, however, Versalles completely lost his ability to play baseball. By 1967 Versalles was one of the worst starting regulars in the league; both his on-base and slugging percentages fell below .285. Sportswriter Doug Grow once asked Griffith what happened. Griffith told him, “drugs.” Versalles had been prescribed pain killers for a chronically bad back. Unfamiliar with the culture and the language, Versalles often ignored the correct dosage, taking well over the prescribed amount.1

How exactly leadership of a baseball team affects performance on the field has long been debated. The Oakland A’s of the 1970s fought each other and owner Charles Finley to three World Series victories. In many other instances, however, turmoil and dissension have often been used to explain the failure of otherwise talented clubs. The Twins of the late 1960s were fractured into several distinct cliques, and unlike the A’s with a strong, skilled manager in Dick Williams, they had no one with a firm hand on the reins.

Twins owner Calvin Griffith grew up in baseball and by the early 1960s directed a truly family operation. Brothers Sherry, Jimmy, and Billy Robertson along with brother-in-law Joe Haynes all held down key executive positions within the organization. By the time Griffith moved the franchise to Minnesota, he had become an astute judge of baseball talent and was ably assisted by his family and scouts. Moreover, prior to the death of Haynes in 1967 and Sherry in 1970 and the changing baseball economics that Griffith never really understood, the Twins organization should be regarded as one of the league’s more successful, both on the field and in the stands. Over their first decade after moving from Washington to Minnesota in 1961, the Twins actually led the American League in attendance.

Twins owner Calvin Griffith grew up in baseball and by the early 1960s directed a truly family operation. Brothers Sherry, Jimmy, and Billy Robertson along with brother-in-law Joe Haynes all held down key executive positions within the organization. By the time Griffith moved the franchise to Minnesota, he had become an astute judge of baseball talent and was ably assisted by his family and scouts. Moreover, prior to the death of Haynes in 1967 and Sherry in 1970 and the changing baseball economics that Griffith never really understood, the Twins organization should be regarded as one of the league’s more successful, both on the field and in the stands. Over their first decade after moving from Washington to Minnesota in 1961, the Twins actually led the American League in attendance.

Despite his success, Griffith represented the last of the family owners; by the late 1960s baseball teams were owned by men who had made their fortunes in other lines of work and bought into baseball. Because Griffith operated as his own general manager and was not particularly skilled at leadership, he often micromanaged and rankled those who worked for him, somewhat akin to the problems George Steinbrenner experienced in the 1980s when not buffered by a solid general manager. His desire for hands-on involvement also occasionally hindered his hiring judgment.

After a disappointing 1964 season in which the Twins won only 79 games, Griffith cut manager Sam Mele’s salary by $3,000 and publicly criticized his manager for being “too nice a guy” and managing a team that played sloppy baseball. Mele’s managing philosophy of offering criticism and encouragement in private and highlighting what he wanted each player to practice, but not providing a lot of specific instruction, played into Griffith’s concerns.2

To remedy the situation, Griffith foisted two brilliant but strong-willed coaches on Mele: pitching coach Johnny Sain and third-base coach Billy Martin. Much of the hullabaloo surrounding Sain derived from his tendency to separate the pitchers from the position players. Many pitchers he coached were his ardent students and in particular on the Twins, Jim Kaat. Martin was a ferocious competitor and helped enormously in relating to the Latino players. He was also a short-tempered, paranoid bully.

By 1966 Martin and Sain hated each other, and Mele was at odds with his pitching coach as well. The antagonism flared midseason in Kansas City when Sain confronted Martin after the third-base coach had cussed out a pitcher over a squeeze play. Martin and Sain were both angry and neither felt that Mele sufficiently took control of the situation. Moreover, in the aftermath of the altercation, players began to take sides, always a dangerous situation. After the season in which the Twins finished 89–73, nine games behind the Orioles, Griffith jettisoned Sain. In response, star pitcher Jim Kaat, who finished 25–13 and surely would have won the American League Cy Young Award had the award been bestowed in both leagues, sent a widely-circulated open letter defending Sain and criticizing the decision to fire him.

Finally, after a 25–25 start to the 1967 season, Griffith fired Mele and promoted Cal Ermer from the Twins triple-A farm team in Denver. Ermer found himself in an almost impossible situation: a man with little major league experience as either a player or coach thrust into a team fractured into cliques, both racial and otherwise, made up of stars who had tasted a pennant, and with a hands-on owner breathing over his shoulder.

To Calvin Griffith’s credit, he had assembled one of baseball’s more racially mixed teams. Many of the team’s stars were African-Americans and Cubans who would have been banned for being too dark-skinned before 1947. But race relations in America in the 1960s were in flux, and baseball was not exempt. Just twelve days into his tenure, Ermer was faced with a difficult situation on the team bus in Detroit, a city teeming with racial tension.

White pitcher Dave Boswell was playing with a gun, when Grant, who is black, told him to put it away. When Boswell ignored him, Oliva also told Boswell to knock it off. “You Cubans play with guns down there,” Boswell reportedly replied. “We got a right to play with guns up here.”3 Sandy Valdespino and Ted Uhlaender nearly came to blows, before cooler heads held them back. Ermer went to the back of the bus to calm things down and later held a meeting at the hotel to simmer down the tensions. Many of the black players remained unconvinced, but there can be no doubt that the team responded on the field. “Cal Ermer was a great guy,” Kaat remembered. “I don’t know if he ever had control over big league players, but he was a different presence than Sam and it worked for the rest of that season.”4 At least for the next 112 games: the Twins went 66–44 (with 2 ties), taking a slim lead in the pennant race.

But the Twins could not seem to shake their controversies. Holding onto a one game lead, the team once again faced off against itself on September 29. In a contentious players-only meeting to divvy up the World Series money (a small portion was also allotted to high finishing teams that did not win the pennant), many of the players argued against giving Mele a share. Once this had been pushed through, five members the pro-Mele faction symbolically voted not to give Ermer a share either. More substantively, eleven players agreed to pool their own shares to give Mele a portion. Even the commissioner’s office felt the need to weigh in and castigate the players but otherwise took no action. In the aftermath of this dramatic meeting, the Twins lost the final two games of the season, and the pennant, in Boston.

The team’s success under Ermer over the last half of 1967 did not translate into 1968. In addition to the players’ drop-off noted earlier, Killebrew suffered a brutal hamstring injury that contributed to a 79–83 record. “It has been quite apparent to me that Ermer has lost control over the club,” Griffith complained late in the season.5 Moreover, this was not a lone sentiment. “Cal Ermer was a weak man,” wrote catcher John Roseboro. “He was quiet like [Los Angeles Dodgers manager Walter] Alston, but he didn’t have Walt’s firmness and he didn’t have the respect Walter had.”6 Griffith, a lifelong baseball man with strong opinions of his own, too often exacerbated the situation by criticizing Ermer, making it hard for him to exercise the necessary managerial authority.

With the firing of Ermer, for 1969 Griffith finally relented and hired fan-favorite and domineering personality, Billy Martin. In this first year of two divisions, Martin brought the Twins home first in the West. With young star Rod Carew and several other quality newcomers having joined the aging nucleus of 1965, the Twins could still perform at a fairly high level. But it was too little, too late. The Orioles had built a superior ballclub in Baltimore, ranked by some as one of the greatest of all time. The Twins window of opportunity had closed.

In one of the odder mistakes, the Twins had a potentially great pitcher that they simply didn’t use. Early in 1963 season the Twins traded for Cleveland’s Jim Perry, a good pitcher who had been struggling recently. During Perry’s first two years in the majors, 1959 and 1960, he had won thirty games, while leading the league in wins, starts, and shutouts in 1960. He fell off over the next couple of years, but with the help of Twins pitching coach Johnny Sain and a new curveball, he rejuvenated his career in Minnesota. For some reason, however, the Twins relegated Perry to the periphery of the rotation, essentially keeping him as a swing man from 1965 to 1968. Only once during those four years did Perry start more than 20 games despite having an ERA better than any rotation regular in three of them. When Martin finally put Perry into the rotation in 1969 he went 20–6. The next year he won the Cy Young Award with a 24–12 record. Perry currently holds the Twins career record for lowest ERA (minimum 750 IP) at 3.15 and finished with a career total of 215 wins.

By 1965 Calvin Griffith had built a terrific young team in Minnesota. The team won the American League pennant by a comfortable margin and came within a Sandy Koufax three-hitter of winning Game Seven of the World Series. Griffith, a life-long baseball man, had built a solid organization manned primarily by baseball savvy family members and close friends. The team drew well at the gate, and Griffith paid his players well by the standards of the time. But this group of Twins players could not repeat. Too many of the stars suffered unexpected rapid and severe declines, and in fairness to Griffith, it is almost impossible to know when a star is truly declining and when it is simply a one-year aberration, especially at the young age of many of his players. Furthermore, Griffith did continue to add talent over the next couple of years, most notably second baseman Rod Carew.

Griffith also seemed to lose control over the team. The team bickered and fought with itself in nearly every possible permutation: coach versus coach, coach versus management, and player versus player. Until hiring Martin in 1969, Griffith was unwilling to vest in his managers the sort of authority necessary to truly manage a diverse group of stars with strong personalities. In the years after 1965 a combination of bad luck and ill-defined manager control thwarted the Twins from reprising their success.

DANIEL R. LEVITT is the author of “The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy,” released in the spring of 2012 by Rowman & Littlefield under its Ivan R. Dee imprint. He is also the author of “Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty,” a Seymour Medal finalist and co-author of “Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got that Way,” winner of The Sporting News-SABR Baseball Research Award. He lives in Minneapolis with his wife and two boys.

Sources

Anderson, Dr. Wayne J. Harmon Killebrew: Baseball’s Superstar. Salt Lake City: Deseret Books, 1971.

Armour, Mark L. and Daniel R. Levitt. Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way. Washington D.C.: Brassey’s, 2003.

Carew, Rod with Ira Berkow. Carew. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Furlong, Bill. “The Feuding Twins: Inside a Team in Turmoil.” Sport, April, 1968.

Golenback, Peter. Wild, High and Tight: The Life and Death of Billy Martin. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Jordan, Pat. “In a World of Windmills.” Sports Illustrated, May 8, 1972.

Kerr, Jon. Calvin: Baseball’s Last Dinosaur. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown, 1990.

Leggett, William. “A Wild Finale—and It’s Boston.” Sports Illustrated, October 9, 1967.

Nichols, Max. “The Kaat Organization.” Sport, December, 1966.

Nichols, Max. “Sam Mele: A Study in Pressure.” Sport, April, 1966.

Roseboro, John with Bill Libby. Glory Days with the Dodgers and Other

Days with Others. New York: Atheneum, 1978.

Smith, Gary. “A Lingering Vestige Of Yesterday.” Sports Illustrated, April 4, 1983.

Sporting News Baseball Guides. 1965 through 1970.

Sports Illustrated. “Minnesota Twins.” April 18, 1966.

Urdahl, Dean. Touching Base with Our Memories. St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press of St. Cloud, 2001.

Williams, Jim. “Which Is the Real Jim Kaat.” All Star Sports, August, 1968.

Zanger, Jack. Major League Baseball. 1965–1970. New York: Pocketbooks.

Notes

1 Doug Grow, Phone Interview, February 21, 2011.

2 Max Nichols, “Sam Mele: A Study in Pressure.” Sport, April 1966. 81.

3 Bill Furlong. “The Feuding Twins: Inside a Team in Turmoil.” Sport, April 1968. Rod Carew with Ira Berkow, Carew. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979) 82.

4 Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 21, 2007, C8.

5 Jon Kerr. Calvin, Baseball’s Last Dinosaur: An Authorized Biography. (Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown Publishers, 1990) 78.

6 John Roseboro with Bill Libby. Glory Days with the Dodgers and Other Days with Others. (New York: Atheneum, 1978) 230.