Action Jackson: Watching Baseball Remotely, Before TV

This article was written by Eric Zweig

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

With the weather turning crisp in October of 1916, sports fans across North America were looking forward to the World Series. There had been great pennant races in both leagues, and the upcoming battle between Brooklyn and the Boston Red Sox looked like a good one. Though Toronto was still more than sixty years away from joining the American League, interest there in the Series was high. The city was already a hotbed of minor-league baseball.

With the weather turning crisp in October of 1916, sports fans across North America were looking forward to the World Series. There had been great pennant races in both leagues, and the upcoming battle between Brooklyn and the Boston Red Sox looked like a good one. Though Toronto was still more than sixty years away from joining the American League, interest there in the Series was high. The city was already a hotbed of minor-league baseball.

Like most cities, Toronto once had a great many more newspapers than it does today. Among the most prominent in 1916 were the Star and the Globe— today’s lone survivors of this time period—as well as the Telegram, the World, and the News. All of them devoted a lot of copy to the upcoming Series. “Toronto’s baseball sympathies are with the Boston Red Sox in the world’s series,” said the Toronto Star on October 6, “if for no other reason than the fact that the American League champions are under the management of Bill Carrigan, who was formerly a catcher on the staff of the Toronto club.”1

Toronto newspapers wrote not only of the personalities, the teams, and the excitement that was building in Boston and Brooklyn. They let Torontonians know how, and where, they could follow the 1916 World Series “live.”

In his book Past Time: Baseball as History, Jules Tygiel writes:

As early as the 1890s communities began to translate telegraphic reports of baseball games into visual recreations. . . . After 1905, when the World Series became a permanent fixture on the national scene, scoreboard-watching became an equally entrenched annual ritual. Newspapers erected large displays in front of their offices, attracting crowds numbering in the thousands. . . . In 1906, the Chicago Tribune began the practice of renting armories and theaters to hold the crowds. The indoor setting allowed scoreboards in the major cities to become increasingly more elaborate.2

At least two elaborate American scoreboard devices made their Canadian debuts in Toronto for the World Series of 1916. According to the Globe, “The Nokes Electrascore Board, which will be at Massey Hall, is the only one yet invented which satisfactorily shows the actual movements of each player. . . . The board stands upright in full view of the spectators, and the moving lights can be plainly seen from any part of the hall. Mr. Nokes, the inventor of the board, has arrived in the city to set up the board, and will be here throughout the entire series of games.”3 Tickets to watch the “games” at Massey Hall could be purchased for 25 or 50 cents.

While I think we all have at least some idea of these devices, from old photographs and from scenes in movies like Eight Men Out, fortunately the Toronto Star provided a few more details on the Nokes board. “To those who are not familiar with this marvelous invention, we may state that by means of colored lights for each team the movement of every player is shown and the players are in actual movement all the time. Returns are received by special wire direct from the field the moment the plays are made.”4

While I think we all have at least some idea of these devices, from old photographs and from scenes in movies like Eight Men Out, fortunately the Toronto Star provided a few more details on the Nokes board. “To those who are not familiar with this marvelous invention, we may state that by means of colored lights for each team the movement of every player is shown and the players are in actual movement all the time. Returns are received by special wire direct from the field the moment the plays are made.”4

To judge from the stories that followed, a large number of Toronto baseball fans were entertained by the Nokes Electrascore Board during the World Series. Yet if I were to time-travel to Toronto in October 1916, I would not have been in attendance at Massey Hall. Instead, I would have been at the Arena Gardens. Seated inside the city’s largest hockey rink, I would have watched—or, rather, followed—the World Series on the Jackson Manikin Baseball Indicator.

I had never heard of this mechanical wonder before I stumbled across the following Toronto Star article from October 4, 1916:

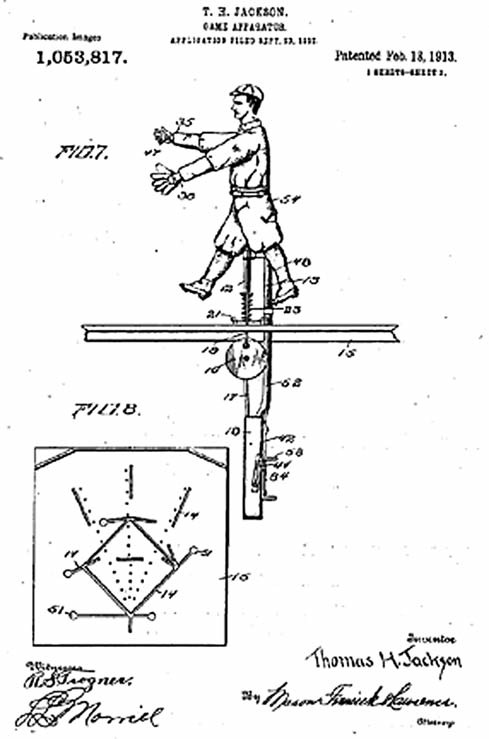

The Jackson Manikin Baseball Indicator, which will be shown at the Arena Gardens for the first time on Saturday afternoon next, is the latest invention of its kind in the world, and so far ahead of all others showing the world’s series games that it is sure to make a big hit among local fans. It is a faithful representation of the game, with diamond, grandstand, fences with advertising on them, and, lastly, umpires and players that do everything but talk. The players throw and catch the ball, run the base lines, slide, run after fly balls, hold consultations on the field and quarrel with the umpire to hide their own shortcomings. The diamond, with scenery, is fairly large, and occupies the full depth and width of the Arena. In the front are shown devices so that the spectators may keep track of the outs, balls, strikes, runs for the inning . . . and in certain plays know whether the runner is out or safe.5

According to an article two days later, it required ten men to keep all the figures in action—ten men, and it filled the entire floor of a professional hockey arena.6 The Jackson Manikin Baseball Indicator must have been a giant-sized version of an old-fashioned baseball arcade game.

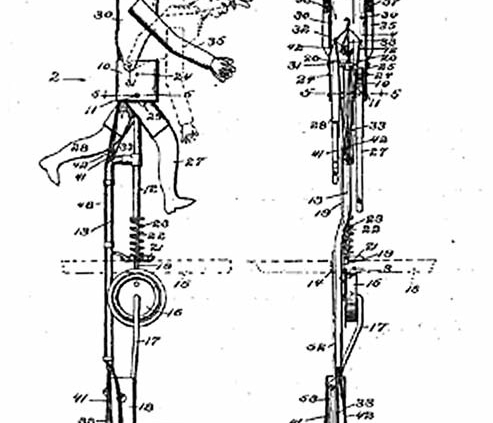

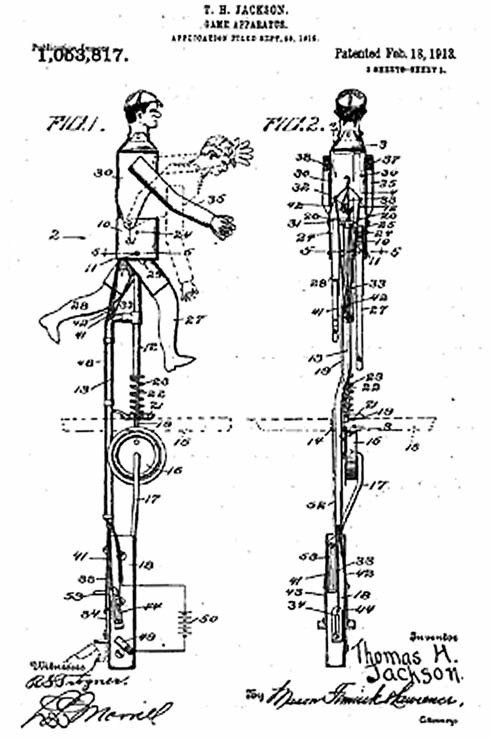

It turns out that the Jackson Manikin Baseball Indicator was invented by Thomas H. Jackson of Scranton, Pennsylvania. He received a patent for it on February 18, 1913, and began using his device to entertain fans that summer in Atlantic City; Washington, D.C.; Rochester, New York; and his own hometown Washington Post, in its Sunday edition on August 17, 19137, reprinted a story that originally ran in Scientific American, giving a detailed report on how the invention worked and what it looked like:

The manikins that enact the plays are themselves about a foot and a half high, but the working mechanism, which is not seen by the spectators, is just as long. . . . Through a system of levers the operator is able to raise either the right or left arm or both, or cause the figure to bend over. In running bases the wheel attached to the manikin fits the base-runner groove, and in revolving causes the legs to move backward and forward. If the operator wishes to make the figure slide into a base, it is necessary only to incline the entire device in the direction desired. . . .

At the commencement of the game . . . the nine fielding players in their white suits come up through holes in the diamond and take their respective positions, and the batter in his brown suit comes up through a hole near the home plate and with bat in his hand takes up his place. A light appears in the pitcher’s hand if he is right-handed, in his right hand, and if left-handed, in his left. [Note: All batters and fielders could be correctly represented as lefties or righties.] After “winding up” he delivers the ball toward the batter. The light in his hand is extinguished, and if the pitcher is inclined to be wild it is shown in the catcher’s hand, the umpire raises his left arm and the announcer calls “ball one.” If the batter makes a safe hit—say for two bases to left field—the progress of the ball is shown on the ground from home plate, between shortstop and third base out into left, where the fielder stoops and the light is shown in his hand. He throws to third base. . . . If, however, the batter merely hit a fly to left field, a light glows over the shortstop’s head, then over the head of the left fielder and then in his hand. [Presumably, groundouts were represented by the ball appearing in, say, the shortstop’s hand. He would then “throw” across the diamond, the light going out in his hand and then the light going on in the first baseman’s hand before the manikin in the baserunner groove reached the bag.] When the side is out, the manikins in white go down through holes and off the field and their places are taken by manikins in brown, while the batsmen are dressed in white. If, perchance, a pitcher is being hit very hard and is taken out of the box, that fact is faithfully presented by a consultation between the captain of the team and his pitcher and the exit of the latter through a hole near his position in the center of the diamond. . . .

Great enthusiasm is aroused among the fans who witness a game on the board: for they see a miniature player representing their pitching idol strike out batter after batter, or the team’s slugger hit the ball to all corners of the field with the fielders in pursuit, or maybe the speedy baserunner stealing bases and sliding beyond the reach of the baseman with all the realism of the game.8

Though the story says nothing about noise, I imagine a lot of rattling and clanking as the manikins pitch, hit, run and field. Perhaps not. Regardless, this was an invention worthy of a Disney theme park. It’s the Hall of Presidents, only with Hall of Famers! And it comes at a time not only before radio or television but also before the widespread use of action photography or motion pictures. It certainly doesn’t take much imagination to believe that the enthusiasm of baseball fans would indeed be aroused well beyond anything that a machine, with blinking lights or magnetic men, could achieve on its own.

So what became of the Jackson Manikin Baseball Indicator? While Toronto newspapers claim it “made a decided hit with local baseball fans,” I have found no evidence that it was used in the city again after 1916.99 Ads from the New York Times indicate that it was still used to follow the World Series until at least 1925.1010 By then, of course, radio had become a fixture of the Fall Classic. While other scoreboard re-creations were still used into the early 1930s, a giant electrical device that required ten men to operate was likely deemed too costly to be able to compete with invisible airwaves that brought the World Series into a person’s living room free of charge.

ERIC ZWEIG is a writer and an editor with Dan Diamond and Associates, consulting publishers to the National Hockey League. A baseball fan since Toronto received its AL franchise when he was thirteen, he worked for the Blue Jays ground crew from 1981 to 1985.

1 “Toronto Fans Pulling for Boston in World’s Series,” Toronto Daily Star, 6 October 1916, 16.

2 Jules Tygiel, Past Time: Baseball as History (New York: Oxford University Press), page 67.

3 “World’s Series at Arena,” [Toronto] Globe, 5 October 1916, 9.

4 “Nokes’ Electrascore Board at Massey Hall,” Toronto Daily Star, 30 September 1916, 12.

5 Toronto Daily Star, 4 October 1916, page 11.

6 “World’s Series at Arena,” Toronto Daily Star, 6 October 1916, 16.

7 “A New Baseball Indicator,” Washington Post, 17 August 1913, page MS3. Further information specific to the patent date was obtained by emails to Washington patent lawyer Thomas Jackson (no relation to the inventor), the Buffalo & Erie County Public Library, and through the web site of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (www.uspto.gov/patents/process/search). The patent number of the Jackson Manikin Baseball Indicator is 1,053,817.

8 “A New Baseball Indicator,” Washington Post, 17 August 1913.

9 “World’s Series at Arena,” Toronto Daily Star, 11 October 1916, 12.

10 New York Times, 7 October 1925, 25.