All-Stars, Amateurs and Acrimony: Gene Doyle’s 1920 Tour of Japan

This article was written by John J. Harney

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

Gene Doyle’s 1920 All-Americans. (Rob Fitts Collection)

It began with big dreams and ended in chaos and farce. The 1920 tour was a lot of things all at once: a high profile, all-star tour that served as a diplomatic mission to engender positive relationships between two rising global powers, the United States and the Empire of Japan; a largely successful business enterprise planned and carried out by experienced entrepreneurs; and a debacle that saw a baseball tour with high hopes collapse in acrimony and accusations of skullduggery. Certainly, it was not boring.

The first mentions of the tour in the American press started to show up in the late spring and early summer of 1920. California-based sports promoter Gene Doyle was promising big things. Specifically, Doyle sought to take an all-star team to Japan to play in exhibition games against local teams. Boasting the cream of the American professional ranks, the tour would feature teams representing each of the major leagues.1 Doyle had successfully persuaded Buck Weaver, star third baseman of an impressive Chicago White Sox team that had rather surprisingly lost to the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series the season before, to lead the group to Japan.

It was not solely an American enterprise. Doyle was in partnership with two Japanese businessmen, Yumindo Kushibiki and Tommy Tominaga. Kushibiki was by this time a well-known figure in the United States, known as the “Japanese Exhibition King” for his work in introducing the American public to Japanese cultural artifacts at the Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893 and, closer in proximity to the 1920 tour, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco. Tominaga was more of an obscure figure, an “Americanized Japanese” who had attended high school in Los Angeles but graduated from Waseda University, a bright star in both Japan’s academic and baseball worlds.2 In truth, he was a fairly minor player who succeeded in establishing himself as a go-between for Kushibiki and Doyle, but his involvement helped give credence to the feasibility of a tour to Japan and lent the endeavor an air of cultural exchange as an act of American generosity.

The advantages of the tour seemed clear enough, at least to Doyle, who utilized a network of contacts in the California press to hype up interest. The visit of John McGraw and Charles Comiskey’s World Tour to Japan in 1913 gave sufficient precedent, and Doyle and his fellow organizers sang all the right notes. This tour would deepen friendship between the two countries, and also allow the Americans to assist their fellow baseball people in Japan to kick-start professional baseball in that country. The commercial advantages also appeared to be evident and the American papers, long since used to the reality of barnstorming and offseason financial opportunities for baseball players, naturally went along in those assumptions.

From the start, then, Doyle’s tour—and in the months to come and in the years since it would come to be associated primarily with its central organizer and promoter more than any of the players—was a hybrid of naked commercial interest and a somewhat ambivalent commitment to deepening cultural ties across the Pacific and facilitating a natural leadership position for the United States in the growth of the game across the world. Doyle had big plans; but it wasn’t to be.

For one thing, Weaver did not join them. Embroiled in the growing Black Sox scandal of the fall of 1920, he dropped out of the tour. He had been the big draw, the biggest name attached to the tour on the day of its announcement. Doyle had intended for Weaver to serve as captain of the AL team and de facto head of the playing squad as a whole.3 Initially, this had seemingly been successful: By July, Doyle was able to claim that Weaver had helped in signing a host of major leaguers, including St. Louis Browns first baseman George Sisler, Detroit Tigers catcher Eddie Ainsmith, and Weaver’s White Sox teammate Happy Felsch.4 Tominaga and others talked a big game indeed, happily comparing the coming tour to the around-the-world Giants-White Sox Tour of 1913.5 It was not to be. Ainsmith, however, stuck with Doyle, and along with Sam Bohne, a Seattle Indian about to begin a career with the Cincinnati Reds in 1921, formed the core leadership of the team. The other big names evaporated.

The rest of the purportedly all-star group was made up of players from the Pacific Coast League, many of whom had a veneer of legitimacy by having had a cup of coffee in the majors. Outfielder Herbert Harrison Hunter had played a handful of games over the years with the New York Giants, the Chicago Cubs, and most recently the Boston Red Sox. Jack Sheehan had appeared briefly for the Brooklyn Robins. One player, catcher Everett Gomes, was so unknown, even to the press on the West Coast, that in reports on the tour they would refer to him simply as “Catcher Gomes.” Still Doyle persevered. Early plans of a tour around California were scrapped, and they moved to head directly to East Asia with a brief stopover in Honolulu.

The Hawaiian reception to the tour was enthusiastic. The local lodge of Elks served as hosts and sponsors of the team, and, expecting a dawn arrival, planned to treat the visitors to a sightseeing trip by automobile around Honolulu, followed by a formal lunch and a game later in the afternoon.6 The Hawaiian hosts got their game—Ainsmith led the AL team to victory over the NL players—but in the end the tourists stopped by the islands for only a few hours. The players returned to the S.S. Korea shortly after and were soon on their way. Doyle was on a high. “So far the trip has been a success,” he wrote to the Los Angeles Express’s Harry Grayson, painting a pretty picture. The players were all in good spirits: Ainsmith was living up to his role of tour captain well, “[f]ull of pepper and keeps the [players] hustling.”7 Bohne was growing a mustache, and another PCL veteran, Portland Beaver Sammy Ross, was doing a bang-up job running the Filipino band on the entertainment committee. Doyle wanted to be very clear: All was well. So united were the boys, in fact, that to a man they were livid with Minneapolis Millers infielder Carl Sawyer, the latest player to drop out. “[W]hat the gang thinks of him isn’t fit for print,” Doyle told Grayson.8

This merry band arrived in Japan ready for anything and everything. The Japanese baseball world gave it to them. The visit, coming in late November and December in the offseason between fall and spring collegiate seasons, was primed for the attention of an enthusiastic and knowledgeable baseball-loving public. Baseball in Japan by 1920 was continuing to grow, with increasingly sophisticated youth and collegiate baseball infrastructures but a still-nascent professional scene. Excitement for the visit of the Americans was high. The Osaka Mainichi Shimbun reported on the anticipated arrival of the team on November 22, scheduled at 3:30 P.M. on the S.S. Korea. The article showcased large photographic inserts featuring a number of the players, including the aforementioned Carl Sawyer. News of Sawyer’s “treachery” had not yet reached the Japanese editors. The Americans themselves were ready for Japan, the paper said that they had been “swinging bats and leaping about the deck” of the ship in anticipation of landfall near Tokyo.9

The opening game in Japan, a competition between teams representing the AL and the NL to fit the tour’s billing as an all-star tour from the major leagues, took place on November 25. The occasion had actually been delayed two days by rain, despite Doyle and Kushibiki’s original intention for the players to get to work almost as soon as they made landing in Japan, perhaps taking to the field on the day of arrival. Nevertheless, the opening exhibition was a success. The NL came out 2-1 winners, but Ainsmith was heralded as the big star, blasting the only home run of the game.10

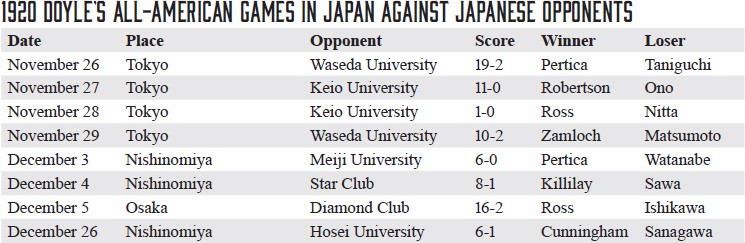

The Americans played their first game against Japanese collegiate opposition the next day. Waseda University was home to arguably the most prestigious baseball program in Japan. Waseda had played the first intercollegiate varsity baseball game in the country, a 1903 contest vs. Keio University. By 1920, Waseda was one of six major college teams. In 1924, these teams would formally come together to compete annually in the “Big Six League”; but already the universities played each other in a de facto annual championship with fall and spring seasons. The All-American team faced four collegiate teams in total: Waseda, Keio, Meiji University, and Hosei University. This represented the top tier of Japanese baseball talent, the best-drilled, and—despite their youth—the most competitively seasoned.

The Americans won 19-2 in the most lopsided game of the tour. If the Japanese baseball public felt any humiliation at the result, they hid it well. If anything, the astounding score only verified further the visitors’ bona fides. Here surely was a great American side, the best possible baseball team visiting to play on Japanese fields.11 The visitors struck out only three times, with 13 hits to Waseda’s three and six stolen bases with no answer from their hosts. Waseda right fielder Tsunekichi Oshita had a day in keeping with the students’ exuberance and inexperience: His three errors had proved crucial, but he had also gone 2-for-4, including a triple. On the American side, Ainsmith was emerging as the star of the tour, going 3-for-6 (including two triples), participating in turning a double play, and stealing two bases.

Ray French, an established veteran from the Western League and PCL who had by virtue of two games for New York in the 1920 season made it possible to bill him as a New York Yankee, celebrated the win by climbing atop the scoreboard and howling to a crowded stand of Japanese fans below. The tour had begun in earnest.12 French’s antics fit the Japanese press’s presentation of the visit neatly, as a fusion of advancing diplomatic and cultural relations between the two countries and as a wild celebration of the fun in baseball. Newspapers ran pictures of the large crowd entering the stadium, holding American and Japanese flags aloft together, and of Gene Doyle with his captains Ainsmith and Bohne, all relaxed or outright beaming with pleasure. “Wild fun!” ran the editor’s caption.13

The visitors continued to roll against Keio University. An 11-0 win featured 10 hits for the Americans to the students’ three, with a home run from one of the tour’s few bona fide major leaguers: two-way player (and Detroit Tiger) George Cunningham, playing center field. Still, the Keio players had put up some meaningful resistance; the American victory relied on big performances from Cunningham, Wally Hood, and the once-upon-a- time Tiger Carl Zamloch at first base. The rest of the lineup, including Japanese media darling Ainsmith, had a rough day at the plate with only three hits among them. Meanwhile the Japanese press was still reflecting on French’s antics atop the scoreboard against Waseda, with a short bylined feature beside another photograph of the infielder smiling and waving a little pennant from his perch.14

Only a few days in Tokyo remained; the Osaka press was already hyping a packed schedule for the American team once they arrived farther west, with six games in three days in early December. The Americans got into the spirit of things with an exhibition game between the AL and NL players in the morning of November 28 before their second game against Keio. The NL came out ahead, 12-6, with plenty of hits—24 in all—but, perhaps disappointingly for the Japanese crowd, no home runs.

Things took a more positive turn for the local fans that afternoon. The Keio team, led by their pitcher Mori Iida, held the visitors to one run in the closest game of the tour. The students actually outhit their opponents too, by seven to four. The hits by Doyle’s team were spread among only three players, including one by pitcher George Ross to go with his shutout, while all but two of the Keio players got on base during the contest. The Americans stole only one base, an area where they had dominated their opponents since arriving in the country, and the young Japanese players committed fewer errors, with only two to the tourists’ three. Still, the result did not follow. Keio’s resistance broke in the sixth inning, when Ainsmith scored the winning run after reaching base on a triple. But Japanese pride received a bit of a fillip when Herb Hunter, who had umpired the game, expressed his astonishment to the Japanese reporters present at the delightful skill of the Keio players.15

Keio had proved that Japanese ballplayers deserved to share the field with seasoned American professionals; after the tight 1-0 game on November 28, everyone could relax a little and enjoy the fun. Doyle’s men played their part. Their second game against Waseda ended with another resounding win, 10-2, before the Americans moved on to Kobe.16

The Kansai region, home to the cities of Kobe and nearby Osaka, was ready for them. The failure of the White Sox and Giants in 1913 to play any games in Kansai was a bit of a sore point; Osaka saw itself as just as much a major city as the capital, Tokyo, and its vast and growing economic and industrial output was home to a vigorous baseball community. The Mainichi Shimbun welcomed the tour with a brief article in English on its front page. “Of all the good things brought to this country from America, perhaps the most Japanized is Base Ball,” it read. Kansai was home not only to many high-school and collegiate teams but to “many Base Ball teams organized not by students but by businessmen.”17

The tourists’ days in Osaka and Kobe saw them six games in a hectic three days, during which the Americans played exhibition games between NL and AL sides in the morning and faced Japanese opposition in the afternoon. The first team, scheduled for December 3, was more collegiate opposition: Meiji University, one of the baseball programs soon to form the “Big Six League.” On the two days immediately following they faced the Star and Diamond ballclubs, teams composed of players from across the college sides they had already faced on the tour.

The interest around the games, and the Mainichi Shimbun’s promotion of them, was tremendous. The newspaper for days framed the three-day schedule in the very center of its front page, and on December 3, the day of the opening games, showcased a letter in English from a Mr. M. Tamagawa of Hiroshima in which he gushed about the American game but also stressed its universal appeal and its value to the Japanese: “I am for the Base Ball—manly, beautiful, healthy game, and believe that it should be encouraged in all schools and should be nationalized as in America.”18

The manliness of the game seemed confirmed a few pages later, with a large photograph of a large, somewhat abused-looking hand reaching out through the middle of the page. “Ainsmith’s knotty hand” ran the headline, as the article reminded Japanese readers of Ainsmith’s work as batterymate to the legendary Walter Johnson—no small part, either, of Ainsmith’s fame back in America.19 He was very much put forward to the Kansai public as the star of the tour. “Fan focus will be on manly Ainsmith,” the paper stated confidently, under a photograph of a large and enthusiastic crowd greeting the visiting players at Umeda railway station in Osaka.20

Manliness aside, Ainsmith and his teammates delivered. On the morning of December 3, they played a tight game, which the NL won 2-0.21 They then dispatched Meiji University, 6-0, that afternoon, a result that confirmed the Americans’ superiority without unduly humiliating their hosts. Ainsmith gave his Japanese fans plenty to cheer about, with a putout at home that earned acclaim in the newspaper report and a large action photograph to honor the moment. Below Ainsmith’s heroics lay photographs of French—apparently now fully inhabiting the role of the barnstorming team cheerleader—dancing and leaping in frenzied joy, and of Doyle with his two captains, carrying gifted floral arrangements large enough to hide the athletes from their knees to their necks. The mood overall was a friendly one. Ainsmith spoke to reporters after the game and was sure to stress that although the Meiji boys had lost, they had shown courage, and that the pitchers’ fastballs and skillful curveballs had given the American pros plenty to worry about.22

Next came the Japanese teams drawn from the combined collegiate rosters. The Star club went down to the tourists 8-1, with a Wally Hood home run to excite the crowd.23 The next day the Americans defeated the Diamond club, 16-2, in their biggest win on the tour since the opening day against Waseda University. By this point, the exhibition all-star games between AL and NL teams had become the prime draw. Large photographic spreads in the papers of crowds for the allstar games, AL and NL captains greeting each other, and a group photograph of Japanese and American men in suits smiling and holding aloft flags from both countries dominated Japanese readers’ attention.24 In contrast to the one-sided victories over the local teams, the Americans put on a great show when playing the intrasquad games. The NL half of the touring team came out as winners of the three-game series with close 2-0 and 4-3 wins on either side of a 5-4 win for the AL. Despite another game later in the month, a 6-1 win over Hosei University on December 26, the Japanese leg of the tour felt as though it had come to a grand conclusion.

It was here that everything went wrong. Though there was little hint of it to the Japanese public, the touring players had not been getting on as well as it seemed. In particular, they had fought over money. Many felt that Doyle was holding out on them. Things came to a head and the team disbanded. Doyle took the loyalists with him to the Japanese colony of Taiwan off the southeastern coast of China, where they played seven games against local teams.25 Trips to China itself and to the American colony of the Philippines, which Doyle had advertised somewhat off the cuff while offering little in the way of detail, were either called off or never arranged.

By mid-January, half of Doyle’s squad was on the way home, with some using the layover in Honolulu to complain about what had happened. Players claimed Kushibiki shared at an open meeting in Japan that he had furnished $20,000 for expenses. It was the first many of the players had heard of it. They told stories of paltry sums—with players receiving only 42 yen (just over $20) each, in front of packed houses where each fan paid between 3 and 10 yen—and of Doyle hiding from the players, barricading himself into a room by putting trunks against the door.26 By late January the news was breaking in California newspapers. Frank Gay, Carl Zamloch, Sammy Bohne, Hunkey Schorr, Bill Pertica, Everett Gomes, Don Rader, Johnny Butler, and Jack Killilay had all abandoned Doyle in Asia.27

For his own part, Doyle was quick to hit back. Writing while still in Japan, he complained bitterly of a clique led by Bohne causing trouble from the start.28 A few weeks later, in a generous piece written by his friends at the Los Angeles Evening Express, Doyle repeated his charge that Bohne was a troublemaker who riled up many of the players. Disagreements over money and how to calculate it lay at the heart of the dispute. Doyle denied the charge that he had refused to monitor the take at the gates by stating clearly that he never planned to do so, and claimed that the failure of the players to take up the job showed they “either figured they were getting a square deal or they hated work.”29 Doyle also shared some more unsavory tales from the trip, of players throwing biscuits at distinguished Japanese hosts at dinner and of one player wandering hotel corridors in a state that left Lady Godiva “well dressed in comparison.”30 The tour, initially proposed as an all-star expedition featuring the best players from the major leagues, had ultimately imploded amid acrimony and harsh accusations.

As a result, Doyle’s tour tends not to feature highly among the many baseball tours between the United States and Japan. Even in Japanese histories, the 1920 visit has earned relatively scant attention, especially when compared with the tours that followed.31 But there’s no question that Doyle’s team was well received at the time, that it drew big crowds and put smiles on a lot of baseball fans’ faces. For Japanese fans, the story of the tour was straightforward: a team made of major-league players had traveled to Japan to play a series of exhibition games. True, there was no Babe Ruth or any of the now scandalized Chicago White Sox, but for many who attended the games, it seemed that the early dreams shared by Doyle and Kushibiki of a combined major-league tour of Japan had been mostly realized. Despite the one-sided nature of most of the contests, the tight game against Keio University gave Japanese fans some reason to believe their players could compete with professionals from the sport’s homeland. American and Japanese flags had flown together above large crowds clamoring to see the visiting teams.

In the United States the tour was a different story altogether. American readers had little detail of the tour’s events until weeks after the players had left Japan, and then the discussion was dominated by accusations of scandal on one side and sabotage on the other. The grander ambitions of the tour had clearly failed. Yet for all his problems and his mistakes, Gene Doyle had proved it possible that American teams, even if somewhat haphazardly organized, could tour Japan. At least one of Doyle’s party took the lesson to heart and would return: Herb Hunter.

JOHN J. HARNEY is an associate professor of history at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. He is the author of Empire of Infields: Baseball in Taiwan and Cultural Identity, 1895-1968. He received a doctorate in modern Chinese and East Asian history from the University of Texas at Austin. John is a Texas Rangers fan and is still bitter about the 2011 World Series.

NOTES

1 “Plans for Baseball Tour of the Orient,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1920: 1.

2 Harry M. Grayson, “Big League Stars Sail Direct for Japan,” Los Angeles Evening Express, July 7, 1920: 25.

3 “Gene Doyle Will Take All-Stars to Japan,” Los Angeles Evening Express, April 16, 1920: 31.

4 Grayson, “Big League Stars Sail Direct for Japan.”

5 “All Major Ball Clubs Will Tour West and Orient,” Anaconda (Montana) Standard, August 8, 1920: 33.

6 “Elks to Welcome Ball Players of Big League and Show ’Em Around,” Honolulu Advertiser, November 9, 1920: 14.

7 Harry M. Grayson, “Doyle’s Players Enjoying Trip the Orient,” Los Angeles Evening Express, December 11, 1920: 10.

8 Grayson, “Doyle’s Players Enjoying Trip the Orient.”

9 “Dai yakyudan kitaru” (Major League Baseball Team Arriving), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, November 23, 1920: 6.

10 “Honba senshu no shosen” (The First Battle of the Authentic Warriors), Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, November 26, 1920: 7.

11 “Waseda Players Made Game Fight,” Times & Mail, November 27, 1920: 8.

12 “Sasuga wa purofeshonaru” (Naturally the Professionals), Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, November 27, 1920: 8.

13 “Waseda tai beigun daiyakyudan hekitosen” (The Opening Contest Between Waseda and the American Major Leagues Team), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, November 27, 1920: 7.

14 “Keio tai beigun daiyakyudan daiikkaisen” (First game Between Keio and American Major Leagues Team), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, November 28, 1920: 11.

15 “Keiogun no kaiwagi ni shinpan Hantashi odoruku” (Umpire Hunter Astonished at Delightful Skill of the Keio Team), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, November 29, 1920: 7.

16 “Teito no saishusen” (Capital’s Final Contest), Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, November 30, 1920: 7.

17 “Welcome! The American Base Ball Teams,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December 2, 1920: 1.

18 M. Tamagawa, “On Base Ball,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December 3, 1920: 1.

19 “Einsumisukun no fushikuredatta te” (Ainsmith’s Knotty Hands), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December 3, 1920: 7.

20 “Fan no nekkyo ni mukaerarete beiyakyudan no chakuhan” (Boisterous Fun Greets the American Team in Osaka), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December 3, 1920: 2.

21 “Nashonarugun katsu” (National Team Wins), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December 4, 1920: 2.

22 “Honruida wa kyo tobasu” (Home Runs Sent Flying Today), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December, 1920: 7.

23 “Beigun teppeki no shubi o kugutta Sutagun no surudoi kogekiburi.” (American Squad’s Iron Wall Defence Untroubled), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December, 1920: 11.

24 “Beigun ryochiimu no sessen” (American Teams’ Close Game), Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, December 6, 1920: 7.

25 “General and Local,” Japan Times & Mail, December 27, 1920: 4.

26 “Big League Players Back in Honolulu with Criticism of Doyle’s Management of Tour,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 19, 1921: 14.

27 “Double-crossed? Doyle Club Breaks,” Los Angeles Record, January 28, 1921: 30.

28 Harry M. Grayson, “Killefer Heads Angel Band to Elsinore,” Los Angeles Evening Express, March 7, 1921: 25.

29 “L.A. Promoter Gives His Side of Japan Row with Faithless Nine,” Los Angeles Evening Express, March 10, 1921: 30.

30 E.I. Moriarty, “Ball Player Threw Biscuit at Japanese Banquet Declares Gene Doyle,” Los Angeles Record, March 10, 1921: 14.

31 Kenzo Hirose, Nihon no yakyushi (Tokyo: Nihon Yakyusi Kankokai, 1964), 33.