All The Duckys in a Row: In Search of the Real Ducky Holmes

This article was written by Joan M. Thomas

This article was published in Spring 2019 Baseball Research Journal

When quintessential baseball buff Douglas Heeren first approached me about a player named Ducky Holmes, I failed to grasp the depth of the subject. Pointing out my misidentification of Ducky in a team photo in my book about baseball in Northwest Iowa, Heeren simply wanted to set the record straight.1

A young man from rural Akron, Iowa, Heeren had some familiarity with one major-league baseball player known as Ducky Holmes. In 1941, Heeren’s uncle, Robert Tucker, was a first baseman and pitcher for the Dayton Ducks, a Middle Atlantic League team managed by one Howard “Ducky” Holmes. The Ducky Holmes in my book is James William Holmes, who played for and managed the Sioux City Packers in 1908. The photo caption is correct about that, but it incorrectly adds that he “caught for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1906.”

It was Howard, not James, who was a catcher for St. Louis that year. Although Howard Holmes had an extensive career in baseball, his time as a big-league player consisted of a mere nine games for the Cardinals. But the conflation of Duckys does not end there. Enthusiastically handing me articles and records he had judiciously gathered from reliable Internet sources, Heeren proved that at least three different baseball players by the name of Ducky Holmes played in the major leagues during the same era.

Appalled by my own error, I thanked the young man, promising to somehow make restitution. Thus I embarked on a perplexing, mesmerizing quest to detail and separate the three Duckys. Little did I know that my research would yield not just three, but five professional baseball players named Ducky Holmes. Numbers four and five never advanced beyond the minor leagues, but their very existence plunged my study down a multitude of wrong-way paths. Of course, as a historian, that only deepened my stubborn need to “set the record straight.”

The following short biographies should assist anyone seeking the true identity of any one of these Duckys. Here are all five Duckys in a row:

JAMES WILLIAM “DUCKY” HOLMES (1869–1932)

Born in Des Moines, Iowa, James William Holmes, frequently referred to as William, is the first — or some would say “the real” — Ducky Holmes in baseball. Born over a decade before the others, his stretch as a professional baseball player surpasses those of his namesakes by far. A good all-around athlete who batted left and threw right, he proved capable at any position but was typically designated as an outfielder. Significantly, the annals of baseball history portray him as an archetypal bad boy of the sport. Stories of his quick-tempered nature abound. One could easily envision a Hollywood movie featuring him as the title character. There would be no need for hyperbole, as his escapades prove the adage that truth is stranger than fiction.

Born in Des Moines, Iowa, James William Holmes, frequently referred to as William, is the first — or some would say “the real” — Ducky Holmes in baseball. Born over a decade before the others, his stretch as a professional baseball player surpasses those of his namesakes by far. A good all-around athlete who batted left and threw right, he proved capable at any position but was typically designated as an outfielder. Significantly, the annals of baseball history portray him as an archetypal bad boy of the sport. Stories of his quick-tempered nature abound. One could easily envision a Hollywood movie featuring him as the title character. There would be no need for hyperbole, as his escapades prove the adage that truth is stranger than fiction.

The son of Arch and Eliza Holmes, William grew up on a farm near Truro, Iowa, about 40 miles south of Des Moines. At one point during his youth, he worked in the hay camps and barns of the small town of Rolfe. He also caught for that town’s baseball club during the season that was reportedly “Rolfe’s greatest baseball year.”2 William began his professional playing career in Beatrice, Nebraska, sometime between 1890 and 1892, and he was sold to the Western Association’s St. Joseph club in 1893.3 In the same league the following year, he played for Des Moines, then Quincy in early 1895. His first major-league job was with the Louisville Colonels in 1895. From there, he spent nearly a decade bouncing to six more clubs, three more in the National League, then three in the American League. As a player, he posted respectable, sometimes above-average, statistics. His best year was with Baltimore in 1899, when he ended the season with a batting average of .320. By the time a knee injury suffered in 1905 with the White Sox effectively ended his big-league career, he had built a reputation for spawning quarrels and controversy.

While playing left field for Baltimore against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds on July 25, 1898, James William “Ducky” Holmes, a former Giant, responded to fans’ jeers by referring to Giants owner Andrew Freedman as a “Sheeney.” Freedman, who was Jewish, took exception to the ethnic slur. When the umpire refused to eject Holmes from the game at Freedman’s request, he ordered Giants manager Bill Joyce to keep his players on the bench. The umpire then forfeited the game to Baltimore. This sparked an ongoing feud in what SABR’s Bill Lamb describes as a “bruising 17-month battle among National League magnates that culminated in nothing less than the restructure of major-league baseball.”4

Playing for Detroit in 1902, Ducky traded barbs with his former teammate John McGraw in a game at Baltimore. (*See below for a correction.) After getting a hit and heading for third on an infield play, he jumped high and slid into McGraw, resolutely stationed at third, striking him on the knee with both feet. Getting up, McGraw punched Ducky, who landed one on Mugsy’s jaw. The Orioles’ player-manager, destined to manage the Giants for 30 seasons, sometimes called “Little Napoleon,” and eventually enshrined in the Hall of Fame, left the field that day “never to return again as a regular player.”5

Following his stint with Chicago, Holmes purchased the Lincoln, Nebraska, team in 1906, the year it joined the Western League. He served as player-manager for the Class A club, named the Ducklings after him. After finishing second with a 75–74 record in 1906, Ducky’s team started ’07 as the Lincoln Tree Planters. Notably, the Planters’ lead pitcher was Eddie Cicotte, who later gained notoriety in the Chicago Black Sox scandal. At season’s end, Ducky sold the Lincoln Club to Guy W. Green, then purchased the Sioux City Packers in the same league. Several years later, Green contended that at the time of the sale, Holmes manipulated the Lincoln players in an effort to “land them in Sioux City.”6 He claimed that one of the men Ducky tried to influence was center fielder Bill Davidson, who moved up to the Chicago Cubs in 1909.

Ducky’s Packers captured the Western League pennant in 1908. And even if the charge that Ducky tried to recruit Lincoln players was true, it does not appear to have been successful. The next season, Sioux City finished second in the eight-team league, just a hair behind the Des Moines Boosters. Despite his questionable reputation, William “Ducky” Holmes had proven his aptitude for management. That likely persuaded Toledo Mud Hens ownership to sign him as player-manager in 1910.

However, his time with that American Association club was short lived. When he returned from a road trip, the club’s president reportedly called him to task for unspecified offenses. It was also rumored that Ducky wanted his own club and “had bought an interest in the Des Moines club of the Western League.”7 Rather than face firing, he announced his resignation on June 6. News soon surfaced that revealed he had more than baseball on his mind at the time.

The marriage of William “Ducky” Holmes to Merte Rogers, a Sioux City public school teacher, was announced on June 11. The Waterloo Evening Courier reported that the wedding had taken place several weeks earlier while “the Toledo team was playing in the Twin Cities.”8 That of course, would be during the road trip in question. The news item reporting the marriage also included the fact that Ducky had divorced the previous winter. Significantly, in a suit in Rapid City, South Dakota, his ex-wife had charged him with desertion. Yet none of the adverse publicity prevented him from being chosen as manager of the Mobile Sea Gulls of the Southern Association for 1911. But his position there proved contentious from the start.

Late in April of that season, word came of the quarrelsome Mobile manager’s suspension by the league president. Ducky was charged with insulting Umpire Collidower by referring to him as a “common vegetable.”9 The suspension didn’t last long, but neither did Mobile’s new manager. On June 12, Holmes was fired after he engaged in a fistfight with Mobile director Harry Hartwell. One newspaper account claimed that “trouble had been brewing for some time.”10 Following his suspension over the umpire incident, Holmes had been fined $500 for language on the field and for an alleged attempt to get recompense in the sale of pitcher Frank Allen to Brooklyn.11 (Allen would go to the Dodgers in 1912.) Additionally, there were charges that Ducky incited the Mobile players to mutiny, made side contracts, and attempted to keep players from the field in order to cause forfeiture of games.12 The same news story that made these charges reported that Holmes blamed his firing on Southern prejudice against a Northerner.

Taking his dispute with Mobile to the National Commission, Holmes presented his contract as evidence that he was the club’s business manager. He claimed that he should have been paid his salary for the unexpired portion of the contract.13 The end result of his claim, or if he was ever forced to pay the fine, are unknown. There is some evidence that he finished the 1911 season with the Victoria Bees, who finished last in the six-team Northwestern League. The following season found him back managing clubs in the Midwest, starting with a short stay with the Class D Nebraska City Forresters, then back to Sioux City in 1912 and part of 1913. One undated newspaper account of his resigning from the Packers on June 6, 1913, reveals that he had a ranch in Montana. That was reportedly his next destination.14 This fits with records of his time with the Union Association’s Butte Miners in 1914. But he soon returned to Nebraska, managing Lincoln in 1916–17.

In 1918, managing Sioux City again, the restless Ducky Holmes prepared to travel to France to represent the YMCA in war welfare work, but the Armistice that ended World War I canceled his journey.15 Then, in January 1919, his purported interest in the Des Moines club again surfaced. He attempted to purchase that Western League franchise from Des Moines Mayor Tom Fairweather, former president of the Sioux City club. Ducky offered to buy the Class A Boosters outright, with the intention of moving the team to Lincoln, whose club did not have a minor-league franchise at the time. When that offer was turned down, Holmes proposed to lease the Des Moines ballpark and to keep the Boosters in that city. Both offers were refused.16

A curious side note to this story is that in January 1918, a devastating fire had destroyed the former Western League Lincoln ballpark’s grandstand and the clubhouse, which served as caretaker Edward McConnell’s residence. McConnell was away at the time, but his wife and five-year-old daughter were at home and suffered serious burns. Fortunately, the ballclub carried $3,000 insurance on the grandstand. The Lincoln Daily State Journal reported that just before the fire started, Mrs. McConnell heard the sound of an automobile and voices. The story goes on to say: “It is not the belief of Ducky Holmes that anyone would intentionally set fire to the ball park.”17 This sheds some suspicion on Holmes himself, having managed Lincoln the previous season. It is conceivable that he might have had a financial interest in the concern at the time.

Unable to acquire a Western League franchise in 1919, Ducky finally settled for an amateur team in Brownville, Nebraska, in 1920. That year he managed and played third base for the Apple Pickers, and he may have owned the club. The townsfolk were elated that not only would a prominent baseball figure control its team, but that a municipal election yielded a go-ahead for Sunday baseball.18 (Some Midwestern towns banned the practice at the time.) Still living in Brownville early in 1921, Ducky umpired in a number of Class B Three-I League games and also served as “one of Charles Comiskey’s scouts.”19 In July, his contrary nature surfaced in his umpiring, as evidenced by an altercation that resulted in fines being levied on the Moline Plowboys’ manager and a player, and Holmes taking a short leave of absence, which he would soon make permanent. “Ducky Holmes is no longer on Al Tearney’s officiating corps,” the Moline Dispatch reported. “After the breakdown here last Monday it is said Ducky beat it for home in Lincoln, Nebraska. Enuf is enuf, is the way Holmes put it.”20

In 1922, Ducky started the season managing the Fort Smith Twins of the Western Association in Arkansas. Transient as ever, he ended up in Nebraska, helming the Beatrice Blues in July. True to form, late in August, he got into a brouhaha with an umpire and was escorted from the field by the local police. He was promptly fired and “ordered out of the lot for assaulting umpire ‘Dutch’ Meyers.”21 By then, he was no longer married to Merte. She married Elmer Eugene Theno in Lincoln on January 7, 1922.

As time passed, Ducky continued working in baseball as an umpire and scout. In an undated letter from John J. McMahon, an insurance representative from Des Moines, addressed to Billy Coad, owner of the semipro Le Mars (Iowa) Orioles, the writer recommends Mr. “Ducky” Holmes, “a former Western League umpire,” to serve as umpire “in that part of the country.”22 McMahon adds that Holmes “comes reasonable and can also give you reference Chas. Dexter, a former Major League . . .” The mention of Dexter confirms that the Ducky being backed is James William. Charlie Dexter was a teammate of his when he played for the National League Louisville Colonels in the 1890s. As Coad’s Le Mars club was founded in 1926, the correspondence was typed then or later. During that year, Ducky was living in Sioux City, which is near Le Mars. Soon, stories arose that he was bargaining to purchase Lincoln’s Class A Western League Links.23

Apparently, Ducky’s plan to buy the Links failed: During the summer of 1927, a Le Mars paper announced that he had been hired to manage a new Sioux City Stockyards team.24 The city didn’t have a minor-league club at the time. In the same publication, a story appeared about his appointment as coach of the team in Merrill, a small town between Le Mars and Sioux City. Some of the players being sought by Ducky for Sioux City were then with the Merrill and Le Mars clubs.

Finally, after suffering from ill health for several years, James William “Ducky” Holmes died at the age of 63 in his hometown of Truro on August 5, 1932. He was survived by two brothers and two sisters. But he had outlived his ex-wife, Merte. Lincoln newspapers confirm that Merte, Mrs. E. E. Theno, retired from an 11-year teaching position in Lincoln in 1927. She died on October 29, 1929, while on a trip to Pasadena, California. There is no mention of children or of her first husband in her obituary.25 Local news items reveal that people in Lincoln had fond remembrances of both her and Ducky.

In 1911, the Lincoln Star, in a story about Ducky’s career up until then, states, “Holmes has made friends and enemies galore. . . . He is afflicted with a temper that easily breaks bounds, but is gifted with an equal ability to forget grudges . . . he is the best of friends, and a man who always gives all he has to his employers.,”26 In a 1926 Lincoln newspaper story about his interest in buying the town’s Western League team, he is described as a “resourceful, heady baseball general.”27 A Rolfe Arrow story of August 18, 1932, describes him as one of baseball’s best known players, who had a remarkable career in the game. These words intimate a legacy befitting the first, or “real,” Ducky Holmes.

HOWARD ELBERT “DUCKY” HOLMES (1883–1945)

Howard Elbert Holmes, the most colorful of all the Duckys in baseball, was born in Dayton, Ohio. His full career in the sport included catching for one major-league club and a number of minor league teams, umpiring in the minors and both major leagues, founding and managing several minor-league clubs, and serving in an executive position for at least one. References to his nose as an “elongated proboscis” and “big schnozzola,” as Douglas Heeren observed, suggests that it resembled a duck’s bill.28 That may explain how he acquired the moniker Ducky. Although not as notorious for his temperament as James William “Ducky” Holmes, Howard did gain a reputation for being a “fiery manager.”29

Howard Elbert Holmes, the most colorful of all the Duckys in baseball, was born in Dayton, Ohio. His full career in the sport included catching for one major-league club and a number of minor league teams, umpiring in the minors and both major leagues, founding and managing several minor-league clubs, and serving in an executive position for at least one. References to his nose as an “elongated proboscis” and “big schnozzola,” as Douglas Heeren observed, suggests that it resembled a duck’s bill.28 That may explain how he acquired the moniker Ducky. Although not as notorious for his temperament as James William “Ducky” Holmes, Howard did gain a reputation for being a “fiery manager.”29

At the age of 19, Howard “Ducky” Holmes launched his professional playing career as a catcher in 1902 with the Saginaw/Jackson White Sox in the short-lived Class D Michigan State League. He then caught for Savannah in the Sally League for several years before being signed by the Cardinals in 1906. Following his brief stay in St. Louis, he moved on to Indianapolis, then to Canton in 1907. Some records indicate that he played for the Sioux City Packers in 1908, but that is highly doubtful.

Studies of numerous reports of the Packers’ games of 1908, including lineups, never reveal a catcher named Holmes. Player-manager Ducky Holmes is frequently named, and that is, without doubt, James William Holmes. Moreover, there are never two players with the surname Holmes listed. Notably, several April 1908 news items report that the American Association Louisville club’s new catcher would be Ducky Holmes from Dayton.30 On June 25, another story revealed that “Catcher Holmes, of Birmingham, has been reinstated, and will be used regularly.”31 The term “reinstated” does leave some question. Then, late in July, Birmingham announced that catcher Holmes was released to Montreal in the Eastern League.32 So it appears that Howard started the season in Louisville, then went to Birmingham and finally to Montreal. This is the sort of detective work that would have prevented my error of placing him in Sioux City in 1908. That settled, on with the story of Howard “Ducky” Holmes.

After Montreal, Howard played for three Central League clubs over the next four years — Zanesville, South Bend, and Grand Rapids — before taking on his first managing position. In 1913, the Southern Michigan League’s Saginaw club changed its name from the Trailers to the Ducks, after its new player-manager, Howard “Ducky” Holmes. He led the Ducks to pennants that year and the next. His star hurler in 1914 was none other than 20-year-old Jesse Haines. The future Hall of Famer won 17 games. Following one more season in Saginaw, Ducky went on to manage the Class D Frankfort Taylors of the Ohio State League. That season, 1916, proved to be his last as a player and Frankfort’s last with a minor-league club. Howard spent most of the next decade umpiring.

After starting out in the Three-I League in 1917, Ducky signed with the American Association.33 In March 1921, the Nebraska State Journal reported that he was included on the staff of Western League umpires for that season. Later that year, an incident occurred that might have involved James William “Ducky” Holmes, but was likely Howard instead.

During an Oklahoma City-Tulsa game in Tulsa on August 10, 1921, disgruntled fans hurled pop bottles and cushions at umpires William Guthrie and “Ducky” Holmes. “One bottle bounced off Guthrie’s stomach,” reported the Pella Chronicle.34 Outside the park after the game, the two arbiters retaliated by assaulting Sgt. Tom Haines, a war veteran in uniform, who apparently had taken no part in their attack. The local police arrested Guthrie and Holmes, who were fined $50 and $10, respectively. American Legion posts all over the country demanded that they be fired from the Western League and barred from organized baseball. The matter was taken up with the league and with baseball’s new commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

The quandary here is the identity of the umpire named Ducky Holmes. Not one of the related news articles gives a first name, which was often the case with James William “Ducky” Holmes. However, as William was never actually recognized as a league umpire, and Howard was an official Western League ump, that would indicate it was the latter. The pugnacious nature of the Ducky in question proves nothing, as neither Ducky was averse to fisticuffs. Moreover, there was always the possibility of misidentification by the media. Regardless, if Judge Landis ruled on the matter, it did not affect either of their careers. Neither was banned from professional baseball, and Howard went on to umpire in the major leagues. He got a trial in the National League late in 1921 but was held “to the Western” in 1922.35

Following his brief stint with the National League, Howard umpired for the American League in 1923 and ’24. An episode in St. Louis in June 1924 may have resulted in the end of his career as a baseball arbiter. He infuriated fans by ejecting Browns manager George Sisler, catcher Pat Collins, and coach Jimmy Austin. Following the game, he was confronted by an irate fan, who struck him in the eye. Holmes blamed the attack on a conspiracy by gamblers.36 Paul Farina, the disgruntled Browns fan, eventually pleaded guilty to the offense and paid a $25 fine. Explaining his actions, Farina said, “I was excited and did it in the heat of passion.”37 One story claimed that Browns owner Phil Ball made it his business to get Ducky removed from the umpire roster.38 In fact, that was his last season in the majors. He soon turned his attention back to managing.

After purchasing his hometown’s minor-league club in 1932, Howard, who also served as manager, changed the Dayton team name from Aviators to Ducks. By the following season, he’d gained permission to move the club from the Central League to the Mid-Atlantic League. He oversaw the start of lefty Johnny Vander Meer’s professional career, as the future four-time All-Star pitched for the Ducks in 1933. Firmly stationed in Dayton by 1935, when the club was associated with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Howard lived up to his reputation as a fiery manager. He was suspended for three months for striking an umpire. Demonstrating his “colorful” label, he continued to manage the Ducks by signaling from his perch on “an electric tower in back of the ball park.”39 Another incident that year involving Howard “Ducky” Holmes is the stuff of baseball legend.

Just prior to a playoff game between Dayton and Huntington on September 13, 1935, a fan presented Ducky with a real duck as a gift. When none of the Dayton players had reached base by the seventh inning, he took the bird to first base and stationed it there. Relating this story, SABR’s Ira L. Smith claims that Holmes had said, half to himself, that he’d make sure a duck got to first base before the inning was over. He adds, “Very soon thereafter that duck gained the distinction of being the first member of its species to be ‘thumbed’ off the baseball field by an umpire.”40

Howard continued managing the Dayton Ducks through 1942, with brief interruptions in 1939 and again in 1940. Early in August of that year, it was announced that he’d been appointed acting manager of the Michigan State League’s Grand Rapids team, also a Brooklyn farm club. He replaced Burleigh Grimes, who’d been suspended following a dispute with an umpire.41 So it seems the theme of umpire disputes followed Ducky throughout his career.

At one point in 1942, Howard was presented with a huge floral horseshoe by his Zanesville admirers.42 That year was the last season for the Middle Atlantic League, and also for the Ducks. During his tenure in Dayton, he not only managed, but served as president, general manager, and treasurer of the club. After his team folded, he worked in a grocery store for some time. In 1944, an article related that if he could “get away from his war job,” he would attend a meeting of the Ohio State League.43 This indicates that he was still involved in baseball, and was also doing more than working at a store. After suffering two strokes, he died at home at the age of 62 on September 18, 1945. He was survived by his wife, Lillian, who passed away in 1960. Originally buried at Woodland Cemetery in Dayton, Howard’s remains were moved to Calvary Cemetery in Kettering, Ohio, in 1946. His tombstone reads HOLMES — H E “Ducky.”

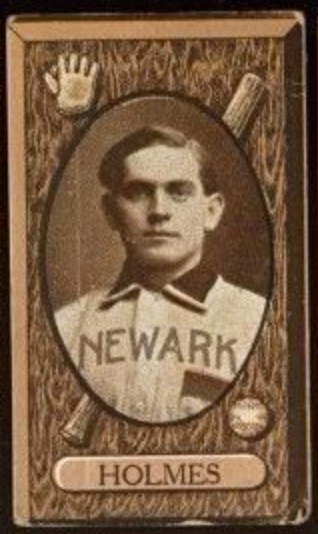

JAMES SCOTT “DUCKY” HOLMES (1881–1960)

Little is known about James “Ducky” Holmes, and news items often confuse him with the other Ducky Holmeses in baseball. What is certain is that he was born in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, on August 2, 1881. He was a right-handed pitcher. His career description on his 1912 Imperial Tobacco card makes the claim that his first “professional engagement was with the Albany Club in the New York League in 1908.”44 Yet all other evidence has him starting with Huntsville of the independent Tennessee-Alabama League in 1904.

Little is known about James “Ducky” Holmes, and news items often confuse him with the other Ducky Holmeses in baseball. What is certain is that he was born in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, on August 2, 1881. He was a right-handed pitcher. His career description on his 1912 Imperial Tobacco card makes the claim that his first “professional engagement was with the Albany Club in the New York League in 1908.”44 Yet all other evidence has him starting with Huntsville of the independent Tennessee-Alabama League in 1904.

He spent time with Augusta of the Sally League in 1905, and his first major-league assignment was with the 1906 Philadelphia Athletics, with whom he appeared in three games. He then went back to Augusta for 1907. There, he tallied his best season, with a 26–16 won-loss record in 1906. His last major-league assignment was in 1908 with Brooklyn, where he appeared in 13 games. He definitely spent the next four seasons with Rochester, then was with Buffalo for parts of 1912 and ’13, and Newark for the rest of the latter year. A January 1914 New York Times story reported that “the veteran pitcher” Ducky Holmes had signed with Baltimore of the new Federal League, but he played for Memphis of the Southern Association that year, his last as a professional player.45

James Scott Holmes’ name as shown under his photo on his Imperial Tobacco card is simply Holmes. The back side description reads only “Ducky” Holmes. Often, news stories call him Jim rather than James. Few details about his life after 1914 are available, but obituaries reveal that he moved to Jacksonville, Florida, in 1928. He worked in the retail grocery business there before he retired around 1950. Then, following an illness of several months, he died in a Jacksonville hospital on March 10, 1960.46

Several news items that appeared after his death contribute to the misidentification caused by too many baseball players named Ducky Holmes. The Brownsville Herald, in a story reflecting on the Augusta club of 1906, refers to him as “the original Ducky Holmes.”47 As James William “Ducky” Holmes was in the game, and called Ducky, almost a decade earlier, it would not seem likely that Jim could qualify as the original. Also, a Florida newspaper story in 1959, while Jim was still very much alive, names him as one of the umpires to officiate at the first game at the original Yankee Stadium. It correctly calls the umpire Ducky Holmes but goes on to say how he once played for Augusta in the Sally League.48 However, it was Howard “Ducky” Holmes who umpired in that first game at Yankee Stadium on April 18, 1923. But Howard never played for Augusta.

The pitcher Ducky Holmes whose major league assignments included Philadelphia and Brooklyn is buried at Riverside Memorial Park in Jacksonville. His tombstone reads “James Scott Holmes.”

ROBERT H. HOLMES or ROBERT S. HOLMES (1884–?)

What little information is available reveals that right-handed relief pitcher Robert H. Holmes, possibly Robert S. Holmes, also called “Bob,” was born in Texas in 1883 or 1884. His professional baseball career consisted of four seasons, and he never rose to the major-league level. There is evidence that he too was called “Ducky.”

In 1908, he appeared in 21 games for the Altoona Mountaineers of the Tri-State League, and then in 26 games in 1909 for Waco of the Texas League. He pitched in 20 games for the Newark Indians of the Class A Eastern League in 1910, and in 37 more the next year. He never had a winning season. The clue to his “Ducky” handle arises from a New York Times report of a 1911 Newark game.

The box score story detailing Newark’s game with Jersey City says that the Indians’ Holmes “was in good form for seven innings.”49 It adds that “Ducky” blew up in the eighth. One could conjecture that the sportswriter had him confused with the other Newark pitcher, Jim Holmes. However, Jim didn’t play for that club until 1913, two years after Bob. Bob’s Imperial Tobacco card dubs him “Pitcher ‘Bob’ Holmes.”50

Unable to track down solid information about this mysterious Ducky, I did locate an R. S. “Ducky” Holmes living in Amarillo, Texas, in the 1930s and ’40s. This might be stretching it a bit, but the “R” could stand for Robert. Moreover, his Texas birthplace enhances this hunch to some degree. Speculations about his possible identity as the former pitcher include several pieces in Amarillo newspapers.

A 1938 Amarillo Globe story about girls softball reads, “Ducky Holmes is interested in forming a girls’ city league and having a tournament.”51 The name R. S. “Ducky” Holmes appears several times in the 1940s, the most helpful in 1945. A story about a Capt. R. S. Holmes Jr. describes his parents as “Mr. and Mrs. R. S. (Ducky) Holmes,” who “now live in Amarillo.” It goes on, “Mr. Holmes for years was a Rock Island Dispatcher.”52 Several stories show that the family lived in Dalhart, Texas, while Ducky Junior was growing up. But nothing turns up with the Dalhart clue. However, in a 1927 story about the Texas A&M Aggies, Ducky Holmes is mentioned as “the Aggies fifth flinger (who) has quit going out for baseball.”53 Considering the date, that Ducky is quite likely Ducky Junior. One more piece of the puzzle, perhaps an irregular piece, is a photo found in a magazine published by the New Haven Railroad for its employees in October 1946. On page 262, in a photo featuring Brakeman “Biddy” Comm and Conductor ‘Ducky’ Holmes, Conductor Ducky’s face looks remarkably like an age-enhanced sketch of Newark’s Holmes on the baseball card.54 And, R. S. “Ducky” Holmes did work for a railroad. But again, that alone does not really prove anything.

Many times there are significant leads in obituaries, but so far none have surfaced for Bob, Robert or R. S. “Ducky” Holmes that prove useful. One hope is that someone reading this will come forward and help fill in the blanks. That would certainly augment baseball history, and honor the memory of pitcher Bob “Ducky” Holmes.

CHARLES M. HOLMES, aka DUCKY HOLMES (1907–1982)

While preparing to wrap up my research, a futile effort, I happened onto yet another minor-league pitcher named Ducky Holmes. Although he was of a later generation than the others, I could not ignore his existence.

In 1927, the Springfield (Missouri) Midgets defeated Fort Smith 9–5, and “‘Ducky Holmes,’ youthful Springfield hurler, was the winning slabman.”55 According to Baseball-Reference, a Charles A. Holmes pitched for the Western Association Midgets in 1927, and then for Quincy in 1928. A 1929 news item reported that Ducky Holmes had been released from the Quincy Indians.56 Another story revealed that Charley “Ducky” Holmes was pitching for the Moline Plowboys by June of that year.57 It also had him living in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, at the time. Baseball Reference lists C. M. Holmes with the Plowboys in 1930.

A June 1930 article in a Burlington, Iowa, newspaper detailing a game between the Burlington Bees and the Moline Plowboys calls him “Ducky Holmes, the bespectacled Moline veteran.”58 As evidenced by a story in a Cedar Rapids newspaper, he was still being considered for the Moline pitching staff early in 1931. The writer reports, “Ducky Holmes and Sally Lambert, veteran right handers, still are the property of the club. . . . Holmes was one of the most valuable flingers on the staff last year.”59 There is one 1934 story that has a Ducky Holmes pitching for the semipro Manchester Hawks.60 In all probability, he was the same Ducky who played for the Plowboys.

Thus, we have good evidence that the right-handed pitcher Charles Holmes who played for the Springfield Midgets, the Quincy Indians, the Moline Plowboys, and most likely the Manchester Hawks are one and the same. His middle initial was “M.,” and, significantly, he wore eyeglasses. And, he was called Ducky since at least 1927, when he played for Springfield.

Fortunately, we have significantly more biographical information about this Ducky than we have about Robert Holmes. Census records reveal that Charles Moore Holmes was born July 31, 1907, to Robert and Sarah Holmes. This is undoubtedly the Plowboys’ Ducky Holmes. He married Elinore B. Berry on September 28, 1935, in Rock Island, Illinois. A 1941 Cedar Rapids City Directory shows him as a foreman at the Quaker Cereal Company there. He died on January 10, 1982, at the age of 74, and was buried at Cedar Memorial Park Cemetery in Cedar Rapids. His wife, Elinore, died in 1993 and was buried beside her husband.

CONCLUSION

Throughout my probe into the quandary of the multiple Ducky Holmeses, I’ve pondered the meaning of the nickname “Ducky.” In earlier centuries, it had been a slang term for a female breast.61 Naturally, that can be ruled out. During the time frame covered in this story, it was often used as a term of endearment pertaining to a male. While doing news archives searches, I’ve found other men named Ducky who were not connected with baseball. One was accused of murder. Another was a prizefighter. Granted, two of the Duckys detailed here were combative, but neither was homicidal or fought for a living. However, it seems all these guys were around during the first half of the 20th century. So, the tag Ducky for a man, especially an athlete, may have been popular then.

Some might suggest that the frequent use of that handle was influenced by Hall of Fame left fielder Joe “Ducky” Medwick. But he came along a bit too late for that. Besides, Medwick did not cherish his nickname, as it was said he got it because he waddled like a duck. One could come up with all sorts of theories, both realistic and farfetched. For instance, Douglas Heeren half-seriously suggested pursuing the origin of the cartoon character Howard the Duck. I actually considered that there might be some connection between him and Howard “Ducky” Holmes. Another even more preposterous notion arose while I searched eBay for images. Inputting “Ducky Holmes” yielded a number of Daffy Ducks as Sherlock Holmes collectibles.

The simple explanation might just be that after James William “Ducky” Holmes gained some prominence in baseball, other players bearing his last name, and/or bearing some resemblance to a duck, got the tag. I have no doubt that there were, or maybe still are, more baseball players out there called Ducky Holmes. But frankly, I would prefer not to hear about them. Case closed.

JOAN WENDL THOMAS, a freelance writer, also writes under the name Joan M. Thomas. A longtime SABR member, she is a regular contributor to the Biography Project, and has written several book reviews for the Deadball Era Committee. Her published books on baseball include “St. Louis’ Big League Ballparks,” “Baseball’s First Lady,” and “Baseball In Northwest Iowa.” A former resident of St. Louis, she now lives in her hometown of Le Mars, Iowa. She can be reached by email at JTh8751400@aol.com.

It was Detroit left fielder Dick Harley who spiked McGraw in 1902, not Ducky Holmes. Harley’s grandson Bob Harley, a SABR member, graciously provided four newspaper stories and the actual date of the incident (May 24, 1902). Both Harley and Holmes were in the game, but Holmes did not reach base. The erroneous information was gleaned from a widely reported story related by Detroit pitcher George Mullin. He went into detail about the spiking, but his account printed in 1907 did not provide the date of the game in question. Thomas searched in vain to determine if Holmes spiked McGraw at some other time. Mullin may have remembered remarks made by Holmes and McGraw correctly, as well as details of the play, but misidentified the player responsible for McGraw’s injury—possibly because both names begin with an “H” and because of Ducky’s reputation as a brawler.

Notes

1 Joan Wendl Thomas, Baseball In Northwest Iowa (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2017).

2 “Noted Baseball Player Makes Final Home Run,” Rolfe Arrow, August 18, 1932.

3 Some news items, including obituaries, erroneously report the year as 1900. Others vary between 1890 and 1892.

4 Bill Lamb, “July 25, 1898: The Ducky Holmes Game,” in Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century, ed. Bill Felber (Phoenix: SABR, 2013).

5 “Ducky Holmes Put Out John McGraw,” St. Louis Republic, July 22, 1907.

6 “Sporting Events,” Lincoln Evening News, June 26, 1911.

7 “’Ducky’ Holmes Out at Toledo,” Waterloo Evening Courier, June 6, 1910.

8 “’Ducky’ Holmes Holding New Job,” Waterloo Evening Courier, June 11, 1910.

9 “Ducky Holmes Suspended,” Le Mars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, April 28, 1911.

10 “Release Baseball Manager,” Galveston Daily News, June 26, 1911.

11 “Ducky Holmes Suspended,” San Antonio Express, July 14, 1911.

12 “Sporting Events,” Lincoln Evening News, June 26, 1911.

13 “Holmes Will Test His Case,” Daily Herald (Biloxi, Mississippi), December 30, 1911.

14 Dean Wheeler, “Ducky Says He Is Done — Veteran Holmes Will Retire to His Ranch in Montana,” unidentified news clipping from 1913.

15 “Ducky Going Over,” Fort Wayne News and Sentinel, October 5, 1918.

16 “Holmes Fails to Buy Club,” Des Moines News, January 27, 1919.

17 “Two Burned In Fire at Ball Park,” Lincoln Daily State Journal, January 24, 1918.

18 “Brownville for Sunday Games,” Lincoln Daily Star, April 9, 1920.

19 “Says the Moline Dispatch,” Rockford Illinois Daily Register, July 16, 1921.

20 Moline Dispatch, July 13, 1921.

21 “Nebraska Minor League Baseball, Nebraska State League, Beatrice Blues,” Nebraska Minor League Baseball History, http://www.nebaseballhistory.com/beatrice1922.html.

22 Letter on Federal Surety Company letterhead addressed to W. P. Coad, Manager, Le Mars Baseball Club, contributed by Bill Coad, grandson of W. P. “Billy” Coad.

23 “Ducky Holmes Dickers for Lincoln Franchise,” unknown newspaper, October 21, 1926.

24 “New Club at Stock Yards,” Le Mars Sentinel, July 19, 1927.

25 “Mrs. E. E. Theno, Former Lincoln Teacher, Is Dead,” Lincoln Star, October 31, 1929.

26 “Sporting Review,” Lincoln Daily Star, July 21, 1911.

27 “Ducky Holmes Dickers for Lincoln Franchise.”

28 Howard Spencer, “The Sportacle,” Sunday Times Signal (Zanesville, Ohio), September 23, 1945.

29 “Ducky Holmes Dies,” Zanesville Signal, September 20, 1945.

30 “A. A. Is Post Graduate School for Central Leaguers,” Indianapolis Sun Sports, April 27, 1908.

31 “Changes in Two Clubs,” Atlanta Georgian, June 25, 1908.

32 Atlanta Georgian and News, July 31, 1908.

33 “Three-Eye Ump Lands Place,” (Davenport) Daily Times, July 12, 1917.

34 “American Legion News,” Pella Chronicle, August 18, 1921.

35 “Newest Umpire in Major Show Is Experienced,” Arizona Republican, March 3, 1923.

36 “Umpire Hit in St. Louis,” New York Times, June 26, 1924.

37 “Hits Umpire, Is Fined $25,” New York Times, July 29, 1924.

38 “Why His Career as Umpire Ended,” Sunday Times Signal, September 23, 1945.

39 “Pilots Although Absent,” Burlington Daily Hawkeye Gazette, June 15, 1935.

40 Ira L. Smith, “Birds, bees, beasts and baseball,” SABR Baseball Research Journal #1, 1972, https://sabr.org/research/birds-bees-beasts-and-baseball.

41 “Holmes in Grime’s Post,” New York Times, August 7, 1940.

42 “Ducky Holmes, Former Dayton Baseball Team Manager, Dies,” Zanesville Signal, September 19, 1945.

43 Howard Spencer, “Ohio State League Meeting Scheduled for Tuesday,” Sunday Times-Signal, December 3, 1944.

44 1912 Imperial Tobacco c46 No. 60, Ducky Holmes, Rochester.

45 “Newark Players for Federal League,” New York Times, January 31, 1914.

46 “James Scott Holmes,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1960.

47 Harry Grayson, “Rucker Hurt Arm Pitching Out of Town,” Brownsville Herald, July 21, 1943.

48 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” The News (Sarasota, Florida), April 10, 1959.

49 “Eastern League,” New York Times, July 7, 1911.

50 1912 Imperial Tobacco No. 79, Holmes, Newark.

51 “In Case You Are Interested Department,” Amarillo Globe, July 20, 1938.

52 “‘Hump’ Veteran Back in States,” Amarillo Globe, June 1, 1945.

53 “Aggies Making Strong Battle for Gonfalon,” Bryan Daily Eagle, May 2, 1927.

54 “The ‘Canal Line’ Crew, I Know a Railroad, October 7, 2006, http://iknowarailroad.net/photoalbum/page262.htm.

55 “Barage of Hits Wins for Joplin,” Joplin News Herald, September 3, 1927.

56 Gilbert Twiss, “Twisters,” Decatur Review, June 5, 1929.

57 “Plow Boys Go to Keokuk,” Moline Dispatch, June 24, 1929.

58 “Moline Takes 2–1 Victory in Hurling Duel,” Burlington Gazette, June 13, 1930.

59 “Parker Has Strong Squad of Veterans at Moline This Season,” Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette and Republican, April 9, 1931.

60 “Dyersville Spills Manchester to Gain on Valley Leaders,” Telegraph Herald and Times-Journal (Dubuque, Iowa), August 17, 1934.

61 William Brohaugh, English Through the Ages (Cincinnati: Writers Digest Books, 1997).