An Epoch in Australian Baseball: Stanford University’s Tour of 1928

This article was written by Ray Nickson

This article was published in Spring 2018 Baseball Research Journal

In 1928, the Stanford University baseball team came to Australia with its coach, Harry Wolter, to play a series of games against local teams. Australian newspapers proclaimed that it would “mark an epoch in Australian baseball history.” The Stanford tour, with its inclusion of an ex-major league ballplayer in the role of touring coach, not only served to raise the popularity of baseball in Australia but also the standard of play. The tour was a significant, yet under-recognized, milestone in the history of Australian baseball.

While the Stanford University baseball team toured Australia in 1928, two groups of Americans met: the Ingenues jazz group and the Stanford baseball team. Photo by Sam Hood. (STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES)

“HOORAY! The Yanks Are Coming,” ran one of the many enthusiastic headlines in the Australian press.1 It was 1928, and in the preceding years, baseball had grown a small but steady following in Australia. Now, baseball authorities had, for the first time, invited an American team to tour for the express purpose of playing baseball.2 Stanford University would come to Australia with its coach, Harry Wolter , to play a series of games against local teams. Australian newspapers proclaimed that it would “mark an epoch in Australian baseball history.”3

The Stanford tour, with its inclusion of an ex-major league ballplayer in the role of touring coach, not only served to raise the popularity of baseball in Australia but also the standard of play. The tour was a significant, yet under-recognized, milestone in the history of Australian baseball. It would mark two significant events in that history: the first international match between an Australian team and a dedicated American nine, and the first international intervarsity baseball game in Australia.4

THE EARLY HISTORY OF BASEBALL IN AUSTRALIA

By 1928, baseball had been played in Australia for more than 70 years. While American miners may have played the game in the gold fields of the Australian Gold Rush of 1851, the first recorded baseball game was played in Melbourne in 1855.5 The sporting landscape in the colony, however, favored team sports that allowed competition against the center of the empire, England.6 When Albert Goodwill Spalding’s World Baseball Tour visited Australia in 1888-89, a significant amount of the news coverage revealed a local suspicion of baseball as a threat to cricket.7 Press condescension was common enough that derisively comparing baseball to the child’s game of rounders was a media convention.8

Australian enthusiasts of baseball had persevered, however, and over the next three decades, the sport would grow in popularity and participation. John McGraw brought the Giants and White Sox to Australia during their 1913-14 world tour, which received considerable interest Down Under. During the same period cricket solidified its position as the Australian national sport, so the perceived threat of baseball became less of a concern. In fact, cricket was instrumental in the growth of baseball in Australia: While cricket dominated in summer, the American game was played in the winter, often by cricketers. Some of Australia’s preeminent international cricketers, such as W. H. Ponsford and Vic Richardson, were also keen baseballers. It was in these circumstances that the Australian Baseball Council invited the Stanford University team to Sydney to play a series of games against local and state teams and a national side in an effort to raise the profile of the sport.

THE 1928 STANFORD TOUR

The tour by Stanford University had been announced many months before the team’s eventual arrival and was keenly anticipated in Australia. Sydney’s leading daily newspaper, the Sydney Morning Herald, declared as early as January that “1928 promises to go down in the annals of baseball in Australia as one of the most progressive in the sport.”9 Baseball had witnessed a relative boom in participation in Australia during the 1920s. The sport had grown rapidly, with expanding city competitions, new junior associations, and the advent of teams in rural Australia evidence of its increased popularity.10 Given the recent growth in Australian baseball, local players, followers, the press, and the general public were keen to test how far the game and its players had developed relative to the United States.11 The Sydney Morning Herald noted that Australian baseball had “had no real test as to the standard attained by our players” and speculated, rather hopefully, that sufficient talent existed in Sydney alone for several teams “which would prove more than a match for American university and semi-professional teams.”12 The value of observing and playing against a properly trained American team was widely recognized in Australia at the time. As one newspaper had noted, “Our players are practically self taught, and to meet a team fresh from the land where the ‘ball game’ is part of the national life, should prove intensely interesting and instructive.”13

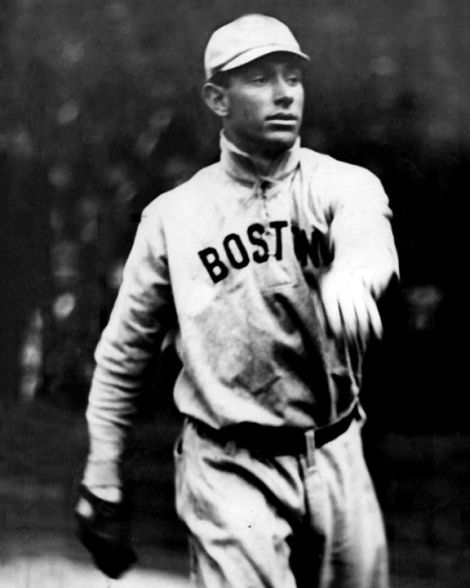

Why Stanford was selected is unclear from contemporary records. The Australian sporting community would have been familiar with the university, however, as Stanford had previously played against the Wallabies, Australia’s national Rugby Union team. Indeed, it is likely that Stanford’s profile as an educational and sporting institution was influential in its selection. Wolter, Stanford’s coach, was sufficiently well-known that Australian newspapers were aware of his professional record: He played seven seasons of major league baseball for a variety of clubs, including the Yankees and Red Sox. In the season immediately before the tour, Stanford had finished with a 7-10 record, ending tied for third in the Pacific Coast Conference at 5–7.14 It was initially hoped that a Japanese team, drawn from the ranks of naval personnel on an anticipated ship’s visit, would also compete in a triangular international series.15 Those plans, however, did not eventuate.

The media interest in the tour was high. It was covered in newspapers across the country, from Sydney to Perth and in the remote rural towns in between. It was evident at the time that despite the increased popularity of baseball in Australia, regular international contests needed to be scheduled to enhance its profile.16 Thanks to the promotional efforts of Australian baseball authorities, the Stanford tour enjoyed much fanfare. Local businesses such as the Australian divisions of Kellogg’s and Studebaker supported the tour. The latter loaned six vehicles for a motorcade procession when the Stanford team arrived.17 Regrettably, the team’s arrival coincided with particularly rough weather that delayed its ship. A large crowd had waited at Circular Quay for the ship to berth and the Westmead Boys Band entertained the onlookers, striking up The Star-Spangled Banner when the ship finally docked.18 The planned daytime motorcade through downtown Sydney instead took place at night, with significantly fewer observers on the street.19

The touring ballplayers were received at a formal civic reception attended by representatives of the federal, state, and local governments, as well as the US consul-general and Australian baseball officials.20 The Stanford players’ sense of humor endeared them to their Australian hosts almost immediately: When the civic commissioner compared baseball to rounders in his formal welcome, a member of the Stanford entourage responded, “I am told this game of rounders is a girl’s game. Having seen your girls is there any chance of arranging a game?”21

In its first game, Stanford met a Victorian state team in front of 10,000 spectators.22 Victoria defeated Stanford 5-3, but it was widely accepted that Stanford had not played to its capacity, having only arrived from a stormy sea voyage two days prior.23 In that first encounter, important distinctions between American and Australian styles of play were clear. The Sun observed: “The Americans impressed with their fast and accurate throwing,” which was much quicker than the long-arm Australian cricket-style throw.24 Similarly, the Americans employed a different, more efficient swing of the bat and hit harder than the Australians as a consequence.25 The infield work of the Stanford men was also considered superior to the Victorians, despite the loss.26 Other features of the game that were novel to the local audience were the “rooting” undertaken by the Stanford teammates and the placement of coaches at first and third bases.27

Stanford’s loss to Victoria was to be its only one of the tour. In the second game, this time against a state side from South Australia, Stanford accumulated 26 runs while giving up only one. That the Stanford team had greater baseball wits was evident in the way it took advantage of South Australia’s deep outfield with short hits.28 In the fifth inning alone, Stanford scored 12 runs.29 The Americans amassed a total of 21 hits and their pitcher, Kern, struck out 11 South Australians.30 South Australia was not helped in its efforts by the nine errors the team made, six more than Stanford committed. The American habit of “rooting” for one’s teammates—or to distract the opposition—continued to be of interest to the newspapers after the second game. The Referee, a leading weekly sports publication, noted that the “chattering by the players appears to be another sideline [in addition to ‘rooting’], and when the whole bunch gets going a cage full of parrots has nothing on them.”31

New South Wales was the next state team to play Stanford. A crowd of 5,000 eager fans had come to watch what “proved to be a fast and high-class game, brimful of clever base running, smart fielding and accurate throwing,” according to the Kalgoorlie Miner.32 Stanford scored first when a hit to left field by Maguire brought in Harder, and it added eight more runs by the seventh inning. New South Wales was shut out until the sixth before scoring four runs. The Australians managed a brief rally in the eighth when, with two outs, they scored three runs on a Texas Leaguer by Levy, which allowed Agnew and Guthrie to get home before Levy also scored on an erratic throw by Berg (Stanford’s catcher) that sailed over the head of the Stanford second baseman, Garibaldi. Highlights of the game included Busch, Stanford’s shortstop, being called out for running wide of the base path and Berg making four hits, including three doubles.33

The three games against state teams had been a prelude to the most anticipated fixture on the schedule so far: the first game against an Australian national team. On Saturday, August 4, Australia played Stanford at the Agricultural Ground in Sydney in front of 15,000 fans.34 The game was billed as “the most important fixture in the history of baseball in Australia” by the newspapers.35 As with the previous games, the Stanford players were said to have thrilled the crowd with their big hits in batting practice.36 Warming up on the playing field had evidently been unknown to Australian baseball: It received significant commentary for its novelty during the tour, and the papers encouraged Australians to adopt the practice as a lesson from the tour.

Stanford scored four runs in the first inning following erratic pitching by the favored local pitcher, Ford. The Americans added another two runs in the second and four more in the third, three of which followed a wild throw by Ford to Emmerick at first base. Australia replied with three runs of its own and Kern was quickly replaced by Lewis as the Stanford pitcher. The tactic of readily replacing pitchers was also a new feature of the game to the Australians, who stuck with Ford on the mound for far too long.37 A readiness to replace pitchers, and always having a pitcher warm, were key lessons that the Australians would take from the series.38 As the Sydney Morning Heraldreported, “There were many in the crowd, who saw their first baseball game, and they must surely have been convinced that baseball has attained an elevated sphere in the curriculum of Australian sport by reason of its intense interest, thrilling moments, quick movements, and clean play.”39 The game had captured the imagination of the locals enough that the crowd was larger than the one at the St. George vs. University match in the popular Rugby League competition held the same day. This first international game was so successful, a leading weekly sports paper felt confident that “There is no reason why baseball, once the crowd has been educated up to its thrills, should not be one of the most popular sports in Australia.”40

A series of lower-profile games was played before the second international game. The next was against a Sydney Metropolitans side of the best players from the local clubs. In adverse weather, the Metropolitans took an early lead, 2–0 after the second inning.41 For the remainder of the game, however, Stanford shut them out, and despite the promising start, the top players from Sydney’s clubs lost 12–2. The poor weather continued and when Stanford played Sydney University two days later, the Sunwrote, “The outfield was a quagmire, making play difficult.”42 That game, which Stanford won 5–2, is notable for being the first ever international university baseball game played in Australia. In an effort to promote the game in the areas surrounding Sydney, the tour next moved to Wollongong, a town 52 miles to the south. The team, accompanied by the Sydney Metropolitans, traveled by motorcade to Wollongong, where they were greeted with a civic reception from the mayor and aldermen of the city.43 Stanford won 7–3, with Garibaldi and Harder both hitting home runs for the victors.

So far, the tour had generated significant interest and the second meeting between Australia and Stanford was keenly anticipated. The adverts that ran in the Sydney papers offered:

Baseball—As Played by Americans—Barracking! Rooting! Brilliant Fielding! Snappy Throwing! Combination Team Work! Big Hitting! Fade-away Sliding! Excitement? Hear the Crowd Roar! Roar With the Crowd! And Become a Fan.44

Another 15,000 spectators were eager and the second international match would not disappoint them. Among the spectators was the governor of American Samoa, Capt. S. V. Graham, who threw out the first pitch.45 The game was a close contest and only decided in extra innings. It was expected that the game would “go down in baseball history as one of the finest expositions ever produced by an Australian nine.”46 The papers blamed the loss squarely on Agnew, the Australian second baseman, who collided with Levy at shortstop in an effort to field an easy fly ball by Garibaldi. The error permitted Wilton, the Stanford center fielder and captain, to dash home. Stanford won 2–1 in 10 innings. It was perhaps a fitting victory for Wilton and Garibaldi, who between them got all of Stanford’s seven hits: Wilton went 4-for-4, including a triple.47

The game was almost overshadowed by what Australians perceived as poor sportsmanship: warming up behind the batter when on deck. The papers were awash with criticism of what was conceived as an unsporting tactic.48 As far away as Tasmania it was complained that “the object of this was presumably to detract attention of the pitcher.”49 The Truth considered it so significant that its headline ran “These Yanks Can Play ‘Ball—The Swinging Bat Tactics Disconcert the Home Siders.”50 It was, the Truth claimed, “a practice new to Australia, and not sportsmanlike, according to our views of the game.”51 The crowds were apparently not shy in venting their disapproval. In many newspaper reports of the game, the “bat swinging” of the Stanford players received more coverage than the play on the field.

A combined Australian university side next played Stanford, losing 31–5. The final international game between Stanford and Australia was played on Saturday, August 18, in front of 10,000 fans. The game was well balanced for much of play, but a four-run fourth inning for Stanford was decisive. In the fourth, Wilton, Garibaldi, and Busch loaded the bases with singles. A series of errors then allowed each to score before Berg came in for the fourth on another error.52 Stanford was the eventual victor, 7–0. The Australian newspapers credited Stanford with a hat trick—three successive wins in the international games. In the final game Harry Wolter earned significant praise from locals for providing coaching and instruction to the Australian players in a generous effort to improve the sport locally.53 A final contest was held between Stanford and New South Wales on August 22. New South Wales was first at bat and scored three runs. Stanford leveled in the bottom of the same inning when Maguire hit the ball over the picket fence, scoring three.54 The match remained close until the sixth inning, with New South Wales leading 10–8. Stanford rallied in the late innings, however, and a series of New South Wales errors allowed the Americas to win their final game in Australia, 21–13.55

CONCLUSION

In addition to the milestones recorded during the tour—the first invitational tour of a baseball team to Australia, first international inter-varsity baseball game in Australia, first Australian nine to play a dedicated baseball team—the tour had a noticeable impact on the game in Australia. Although baseball had already been growing in popularity in Australia, the tour significantly raised its profile. The Truth noted that Stanford’s visit had given baseball “a decided fillip,” and the Arrow wrote that the various well-attended games had “given baseball the biggest boost it has had in the history of the game in Australia.”56 These sentiments were echoed by newspapers across the country, but were particularly emphatic in Sydney, where most of the games had taken place: “Baseball in Sydney has experienced the biggest boost it has ever known by the visit of the Americans,” the Sydney Mail’s H. W. Turner wrote.57 It was, so the press claimed, a much bigger boost to the game than the White Sox-Giants tour had been in 1914.58

An increase in the profile of baseball following the tour led to an immediate increase in participation as well. In the following Southern Hemisphere summer competitions, there was an increase in players, teams, and clubs in Australia.59 Importantly, this increased interest was sustained until the next winter season, in 1929, when participation grew again.60 Beyond that, crowds also grew, with higher attendance at local club fixtures in the wake of the tour.61

The Stanford tour also had an immediate impact on the quality of baseball in Australia. The visitors had demonstrated numerous deficiencies in the way the locals played. Australians were reluctant to replace pitchers, more likely to protest at being relieved, and apparently less inclined to follow directions of their coaches than the visiting Americans were.62 The teamwork that Stanford displayed had impressed the Australians, and it was determined as a result that Australian baseballers lacked a sufficient level of that quality.63 Australians also learned the value of having relief pitchers warm up in preparation for taking the mound, and better batting techniques, including dropping the habit of resting the bat on one’s shoulder when awaiting the pitch.64 All these improvements were evident in the club games that followed. The Sydney Morning Herald observed just weeks after the departure of the Americans that “the tactics displayed by the Stanford University team were extensively adopted in nearly all the [local weekend] games.”65 In Adelaide, those South Australians who had been in Sydney returned with improved knowledge of the game, and Adelaide league games now featured the warming up of relief pitchers, the hook slide, and burnt cork under the eyes.66

Harry Wolter, former major league ballplayer and Stanford’s coach, had clearly demonstrated to Australians the need for quality coaching along American lines. During the tour, Wolter had offered to coach any club or school team that requested his assistance.67 Wolter had given some coaching to juniors during his visit, but the opportunity was not seized by local clubs until the end of the tour.68 One paper lamented that “a whole month of expert tutoring was thrown away—a chance that may not come again for years.”69 In fact, Australian baseball officials had become keenly aware of the need for an American coach and Wolter was enlisted as the Australian Baseball Council’s representative in securing an American to assist local teams.70 This proved a difficult task, as suitable candidates already had lucrative jobs, and the necessary inducement to bring them to Australia was more than local baseball organizations could afford.71 That there was no money for an American coach also reflects the unfortunate situation that Australian baseball authorities lost money on the tour.72 In fact, it was later discovered that the tour had been financed, in part, by funds stolen by an Australian baseball official from his employer.73

Harry Wolter, former major league ballplayer and Stanford’s coach, had clearly demonstrated to Australians the need for quality coaching along American lines. During the tour, Wolter had offered to coach any club or school team that requested his assistance.67 Wolter had given some coaching to juniors during his visit, but the opportunity was not seized by local clubs until the end of the tour.68 One paper lamented that “a whole month of expert tutoring was thrown away—a chance that may not come again for years.”69 In fact, Australian baseball officials had become keenly aware of the need for an American coach and Wolter was enlisted as the Australian Baseball Council’s representative in securing an American to assist local teams.70 This proved a difficult task, as suitable candidates already had lucrative jobs, and the necessary inducement to bring them to Australia was more than local baseball organizations could afford.71 That there was no money for an American coach also reflects the unfortunate situation that Australian baseball authorities lost money on the tour.72 In fact, it was later discovered that the tour had been financed, in part, by funds stolen by an Australian baseball official from his employer.73

The Stanford tour of 1928 was a watershed moment in Australian baseball history. It was the first real opportunity that Australian teams had to play against a dedicated amateur American team. Isolated from the developments that had taken place in American baseball, Australian ballplayers had been “self taught,” and the example set by Stanford was highly educational.74 Infield play, baserunning, batting style, pitching methods, tactics, and conditioning were all elements of the game that improved in Australia following the visit by Stanford, and the game became more popular. The press, which 30 years earlier had been suspicious and disparaging of baseball, was now enthusiastic and supportive of the game in Australia.75 Following the popular success of the Stanford tour, a similar invitation would be extended to the Multnomah Amateur Athletic Club of Portland, Oregon, in 1929. But financial success would not follow popular success, and the momentum built by the Stanford tour was not sustained when future tours proved financially impossible. It is open to speculation, but it is likely that had similar tours been staged beyond the 1920s, baseball’s popularity in Australia would have been greater. The interest generated in baseball by international games against Stanford demonstrated the value of such events.

RAY W. NICKSON is Assistant Professor and Program Director of Criminal Justice at Fresno Pacific University. He has been a keen baseball enthusiast from a young age and most recently played for the Armidale Outlaws Baseball Club, Australia, in their inaugural season. He can be contacted at ray.nickson@fresno.edu.

Notes

1 “Hooray! The Yanks Are Coming—Big Baseball,” Truth, June 24, 1928.

2 “Hooray! The Yanks Are Coming.”

3 “Baseball—American Visit—Prospects for the Season,” Sydney Morning Herald, January 26, 1928. Writing as far away as Perth, the West Australianclaimed that the first match between Stanford and Australia “will go down in the history of Australian baseball as an epoch marking the most important advancement of the sport.” (“Baseball—International Contest,” West Australian, August 6, 1928.)

4 “An Early Start? Record Baseball Season—First Draw Out,” Sun, April 10, 1928;“International Baseball—American Team’s Visit,” Register, May 15, 1928.

5 Bruce Mitchell, “Baseball in Australia: Two Tours and the Beginnings of Baseball in Australia,” Sporting Traditions 7, no. 1 (1990): 2-24.; Joe Clark, A History of Australian Baseball(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 5.

6 Australia was a colony until 1901, when the separate colonial authorities federated to become states in the Commonwealth of Australia.

7 Bruce Mitchell, “Baseball in Australia.”

8 Mitchell.

9 “Baseball—American Visit—Prospects for the Season.”

10 “New Clubs Form—Season’s Outlook—Meetings Arranged,” Evening News, February 9, 1928; “Baseball—American Visit Assured,” Sydney Morning Herald, February 14, 1928; “Baseball Team from U.S.A.—Stanford Coming: Record Season Ahead,” Referee, February 15, 1928; “Baseballers—Prospects of Brilliant Season Opening—Californians Expected,” Arrow, March 2, 1928;“Baseball—Record Season Ahead—To Start April 28,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 14, 1928; “At Bases—Yanks Are Coming Soon—Busy ‘Ballers,” Truth, April 15, 1928.

11 “Hitter’s Record—Baseball’s Big Season—Pitchers are Scarce,” Sun, May 22, 1928; “Baseballers Activities—American Visit: Sydney Premiers Defeated,” Referee, June 6, 1928;“Baseball—American Amateur Team,” Age, June 15, 1928; “American Baseballers—Reach Sydney July 26thFor Mammoth Carnival Fixtures,” Referee, June 20, 1928.

12 “Baseball. American Visit.”

13 “Hooray! The Yanks Are Coming.”

14 “Year-by-year Records,” Stanford University, http://gostanford.com/sports/2014/7/22/209600609.aspx , Accessed January 31, 2018.

15 “’Ball Booming—Japanese Team—Americans, Too,” Sun, February 29, 1928; “Triangular International Games—Japanese Team Invited,” Sydney Morning Herald, February 29, 1928.

16 “Baseball: American Team Coming,” Sydney Mail, July 4, 1928.

17 “Baseball—Stanford University Team—Warmly Welcomed in Sydney,” Sydney Morning Herald, July 27, 1928.

18 “Stanford—Baseballers Here—A Sturdy Bunch,” Sun, July 27, 1928.

19 “Baseball—Stanford University Team—Warmly Welcomed in Sydney.”

20 “’Varsity Baseballers—Visit From U.S.A.” Evening News, July 27, 1928.

21 “Rounders? ‘Lead Us to the Girls’—Baseball Men,” Sun, July 27, 1928.

22 “Americans Impress—Great Baseball Struggle—Stanford University—Crowd of 10,000 Watch the Play,” Sun, July 28, 1928.

23 Clark, in his A History of Australian Baseball, states that Stanford lost 3–1 (51), but this is clearly refuted by contemporary media coverage of the game, which scored the contest at 5-3: “Attaboy Victoria! Lads From Land of Swat Fail to Get Round First Australian Diamond,” Truth, July 29, 1928; “Five to Three—Victoria’s Baseball Win,” Sun, July 29, 1928; “Big Baseball—Stanford University Defeated—Crowd of 10,000 Watch Game,” Sunday Times,July 29, 1928.

24 “Five to Three—Victoria’s Baseball Win.”

25 “Five to Three—Victoria’s Baseball Win.”

26 “Good Sports—Stanford Players Lack of Practice,” Sun, July 31, 1928.

27 “Vocal Aid to Baseball—The Science of Rooting,” Sun, July 29, 1928.

28 “Big Baseball—Rep. Teams in Action—To-day’s Games,” Sun, July 30, 1928.

29 “Baseball—Win for America,” Register, July 31, 1928.

30 Contemporary coverage was inconsistent in providing first names or even first initials for the various players. For consistency, only last names are used here.

31 “Biggest Baseball Carnival in History of Australia—Victorians Deliver the Goods—American Students Fall Down in Pinches—South Australians Chicagoed,” Referee, August 1, 1928.

32 “Baseball Match—U.S.A. Defeats N.S.W.” Kalgoorlie Miner, August 2, 1928.

33 “Baseball—Stanford Wins—N.S.W. Beaten 9-4,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 2, 1928.

34 “First Test—Stanford Leads Australia—Baseball Attracts—15,000 People Watch International Game,” Sun, August 4, 1928.

35 “First Test.”

36 “First Test.”

37 “Baseball—Americans Win First Test—Stanford’s Brilliant Play,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 6, 1928.

38 “Pitchers Wanted—Baseball Needs Them—Record Season,” Sun, September 12, 1928; “Baseball—Notes,” Australasian, September 8, 1928.

39 “Baseball—Americans Win First Test.”

40 “Baseball Stars—Australians Beaten in Baseball Test: Thrilling Display,” Referee, August 8, 1928.

41 “Big Baseball—Stanford v. Metrop.—International Carnival,” Sun, August 6, 1928.

42 “By 5 to 2—Stanford Beats Sydney—’VarsityBaseball,” Sun, August 8, 1928.

43 “Three Teams—Baseball in South,” Sun, August 9, 1928.

44 “Slide! Kelly! Slide!” (advertisement) Referee, August 8, 1828.

45 “One Continual Roar at Second Baseball Test—Baseball Thrills—15,000 Cheer and Cheer—Australia Again Beaten—Graham Pitches Game of Career,” Sunday Times, August 12, 1928.

46 “One Continual Roar.”

47 “One Continual Roar.”

48 “Stanford Wins—Baseball Test—Australia’s Great Game—15,000 Spectators,” Sun, August 11, 1928; “These Yanks Can Play Ball—The Swinging Bat Tactics Disconcert The Home Siders—Stanford Settles Aussies’ Hash,” Truth, August 12, 1928; “Baseball—Second Test Match—Stanford Win Sensationally,” Mercury, August 13, 1928, 8; “Lessons—Stanford Teaches—Third Test Saturday,” Sun, August 14, 1928, 5.

49 “Baseball—Second Test Match—Stanford Win Sensationally,” Mercury, August 13, 1928, 8.

50 “These Yanks Can Play Ball.”

51 “These Yanks Can Play Ball.”

52 “Baseball—Australia ‘Whitewashed’—Stanford Wins Third Test,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 20, 1928.

53 “Hat Trick To Yanks—Australia ‘Chicagoed’ in the Third Baseball Test—Walters [sic] Coaches Our Boys,” Truth, August 19, 1928.

54 “Final Game—International Baseball—Stanford v N.S.W.” Sun, August 22, 1928.

55 “Baseball—N.S.W. Defeated—Stanford’s Last Game,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 23, 1928.

56 “Stanford Left a Lesson Behind Them—Gave Baseball a Big Local Boost—Visiting Manager to Negotiate for Coach for Australian Council,” Arrow, August 24, 1928.

57 H. W. Turner, “Stanford’s Visit: An Appreciation,” Sydney Mail, August 29, 1928.

58 Turner.

59 “Stanford’s Visit Leaves Baseballers Happy,” Sporting Globe, August 29, 1928, 3; “Pitchers Wanted”; “More Clubs—Summer Baseball Season—Rapid Progress—Close Matches Expected,” Sun, October 10, 1928.

60 “Baseballers Expect a Flourishing Season,” Sporting Globe, March 13, 1929; “Baseball—Opening of Season—Record Number of Teams,” Argus, April 29, 1929; “Baseball—Season Opens—University’s Fine Form,” Sydney Morning Herald, May 6, 1929; “Baseball’s Opening—Attractive Fixtures: Teams’ Prospects,” Arrow, May 3, 1929.

61 “Baseball—Close of Season—Keen Competitions,” Arrow, September 7, 1928.

62 “Coaching—Baseball Needs—Imported Trainer?” Sun, August 28, 1928, 10.

63 “Stanford Left a Lesson Behind Them”; “Pitchers Wanted.”

64 “Pitchers Wanted – Baseball Needs Them”; “Stanford’s Visit Leaves Baseballers Happy.”

65 “Baseball—Leichardt Beaten—Last Round Club Games,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 27, 1928.

66 “Baseball—Notes.”

67 Turner, “Stanford’s Visit: An Appreciation.”

68 “Stanford’s Visit Leaves Baseballers Happy.”

69 Turner, “Stanford’s Visit: An Appreciation.”

70 “Coaching—Baseball Needs—Imported Trainer?”

71 “Is It Necessary? Australian Council—Americans May Come,”Sun, November 14, 1928; “Baseball—Americans May Come,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 16, 1928.

72 “‘Nick’ Winter With Marrickville—Club Activities,” Evening News, March 21, 1929; “Interstate Baseball Carnival—S.A. Assn. Has No Say In Change of Venue,” Register News, May 17, 1929; “Baseball—American Visit a Loss,” Sydney Morning Herald, May 30, 1929; “Baseball—Notes.”

73 Ray Nickson, “Multnomah at the Bat: The impact on Baseball in Australia of the Multnomah Amateur Athletic Club’s 1929 Tour,” Pacific Journal (forthcoming).

74 “Hooray! The Yanks Are Coming.”

75 Mitchell, “Baseball in Australia.”