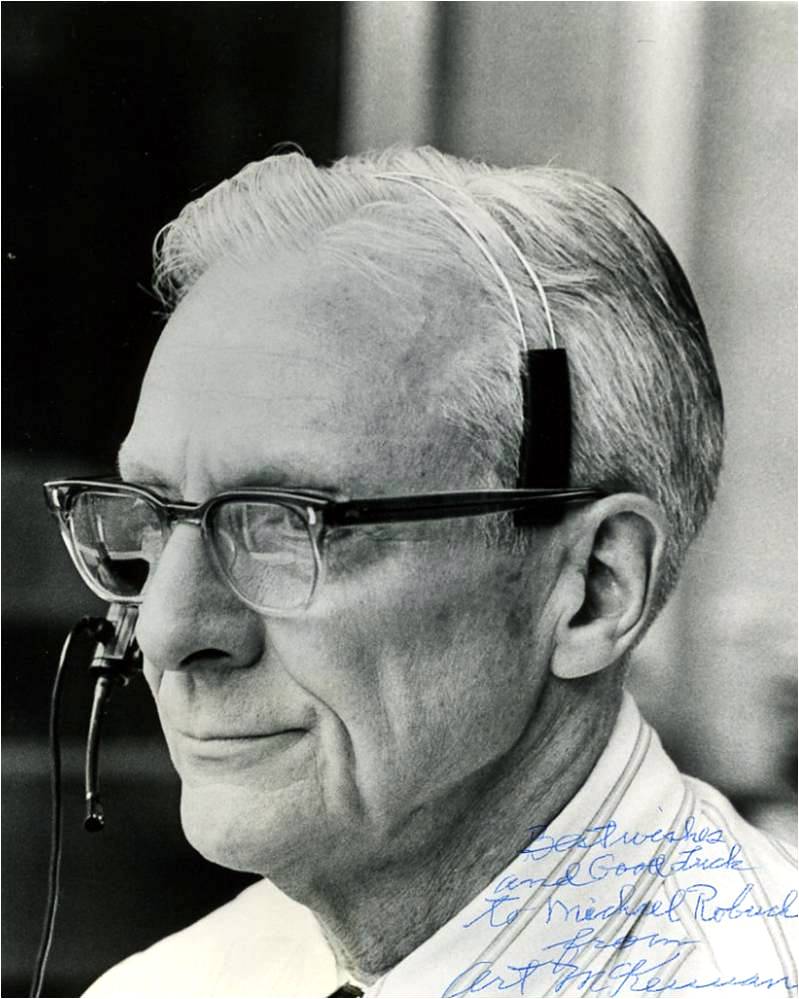

An Interview with Art McKennan

This article was written by Jim Haller - Ed Luteran

This article was published in Baseball in Pittsburgh (SABR 25, 1995)

Art McKennan began his association with the Pittsburgh Pirates as a 12-year-old boy in 1919. He worked many different jobs with the Bucs, from batboy to usher and scoreboard operator for the 1927 World Series, before he became the Forbes Field public address announcer in 1948, a job that brought him his greatest fame. When he retired early in 1993, he spent more than 70 years in the national pastime. This interview was conducted by SABR members Ed Luteran and Jim Haller shortly after McKennan announced his retirement. It was conducted for the Oral History Department of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

E&J: Tell us how you started with the Pirates back in 1919.

E&J: Tell us how you started with the Pirates back in 1919.

Art: My father began taking me to Forbes Field when I was nine years old in 1916. I loved baseball. I loved Forbes Field and its environment. I loved hearing the bats smack the ball during batting practice as we walked near the ball park. I loved hearing the program sellers pitching their wares as we entered the park. I loved the entire atmosphere of Forbes Field. I loved it so much that the occasions my father took me weren’t often enough. So, I decided to go over to the ball park and get a job. This was in the summer of 1919 after school was out. I took my lunch and simply sat by the players’ gate waiting for some kind of miracle. On my first attempt, Billy Southworth came along and took me inside. He played right field at the time for the Pirates and later managed National League pennant winners in St. Louis and Boston. He took me inside the building, but not into the clubhouse. That was against the rules. Manager George Gibson simply would not allow any kids into the clubhouse, for a lot of reasons. I used to sit on the trunks that the team used for traveling around the league. The trunks were located just outside the clubhouse. I would just sit and wait for odd jobs, any jobs. I’d wait for the clubhouse man to come out and give me something to do. After a while, he got very used to seeing me sitting on those trunks, day after day, thanks to Billy Southworth.

The clubhouse man started sending me on errands for the players. He sent me out for lunches. He sent me to the cleaners with dirty clothes and things that needed to be sewn. He made me a real handyman.

Forbes Field had a huge distance from home to the screen behind the plate. It was a little over 100 feet. The Pirates had a “foul tip” boy located at the screen to return foul balls to the umpire in order to save time. The “foul tip” boy was my second job and batboy was my third position with the Bucs.

I was the Pirate batboy for all of 1920 and 1921 and for part of the 1922 season. There was a point in 1921 when we were sure we were going to win the pennant. We were six or seven games ahead of the New York Giants in the latter part of August and feeling very confident. We went to New York, lost a five-game series and never recovered. I had experienced a great high and a great low in a matter of a few days.

In the middle of the 1922 season, one of the fellows operating the scoreboard left and I took his job. It was the “junior” job because two men operated the scoreboard. But it paid one dollar a game, which was more than the batboy position paid: Just a couple balls per game. That’s all. By the end of the 1921 season, I had a trunk full of balls. The kids in the neighborhood loved me. Shortly after I took the scoreboard job, the other operator left and I became the “senior” operator. Two dollars a game. I was still in high school and feeling very proud of myself.

I finally graduated from high school in 1925. I started working for a manufacturing chemist located across the street from Forbes Field. We could actually stand at our upstairs windows and look into Forbes Field and see the games.

But my position there got confused, so I returned to Forbes Field as an usher. In 1926 I started working for a stockbroker in downtown Pittsburgh, and at that point I was completely divorced from the ball club.

In 1927, a friend of mine was running the scoreboard in order to put himself through Pitt dental school. I decided to help him — without pay — during the World Series so that I could spend time on the field with the great Yankees.

No question, the Yankees were great, but they did not intimidate the Pirates as some people have contended. Our guys were professionals. The Yankees did not overwhelm them.

The Pirates had been world champions just two years earlier, and we were basically the same team. A few guys had left, but things were still similar. The Yankees had tremendous power and were very explosive, but somebody dreamed up all those intimidation stories because of the sweep.

I continued working in the scoreboard, helping my friend, for several seasons. In fact, I helped him, not only with the Pirates, but with the Homestead Grays and gained an excellent exposure to black baseball.

In September 1930, I was playing golf in Schenley Park when I noticed that my legs were getting very weak. I was having a very difficult time walking up the hills, and decided to play only nine holes that day. I went home early. Before 48 hours had passed, I could no longer move my legs, even when lying in bed. My Uncle Tom, a neurologist at St. Francis Hospital, was called in to look at me (my father had died in 1924), and he diagnosed polio. At one point some doctors thought I might have meningitis, but my uncle’s diagnosis was right.

He placed me under the care of an orthopedic surgeon who turned me over to a young physiotherapist named Jesse Wright. She was working her way through Pitt as a physical therapist. Eventually, she became a renowned orthopedic surgeon. In fact, there is an annual medical award at Pitt in her honor. I am scheduled to present it next year, and I look forward to the moment. I was one of her first patients.

It took me 11 years to recover and get back on my feet. They got me into the swimming pool at the Pittsburgh Athletic Association, and I swam there for 56 years. I am certain that the swimming has given me the strength to get this far in good shape despite the polio.

E&J: How did you get back to the Pirates after the polio setback?

Art: I started going to the games in a wheelchair. I was sitting in a wheelchair along the right field line, in fact, on a Saturday afternoon in May, 1935, when Babe Ruth hit his final three home runs. He was very methodical that day. He hit the first homer in the lower deck. He smashed the second into the upper deck, and he clobbered the third over the right field roof.

E&J: How did the crowd react to the Babe’s three blasts?

Art: There were some 12,000 to 13,000 people at Forbes Field that day. There was no great reaction in the crowd. There was no overwhelming astonishment. Of course now over 100,000 people have claimed they were there that day. The Babe was not highly overweight as they made him out to be in the recent movie, “The Babe.” In fact, as I recall, he even had a single that day. But, after that day he traveled to a couple more cities with the Braves and then retired from the game.

E&J: What about your return to the Pirates in 1948 as the Forbes Field public address announcer?

Art: Well, I actually returned to the Pirates in 1942. A friend of mine started working with the Pirates at the time the Bucs installed the electric scoreboard, the public address system and the lighting standards. He was the first man to run the electric scoreboard from the press area up behind home plate. He got a regular job in 1942 that prevented him from doing the scoreboard at the same time. I was not working at the time, so he turned it over to me and I ran the scoreboard for the next 50 years.

E&J: Let’s talk about the 1925 World Champs. This team is not well remembered by most people in Pittsburgh today. Who was its best player?

Art: Without question, its best player was Pie Traynor. I saw Brooks Robinson play, and he was an excellent third baseman, but he wasn’t any better than Pie. A writer in Pie’s day coined a phrase: “so-and-so doubled down the left field line, but Pie Traynor threw him out at first.” He made all kinds of plays at third base, especially bare-handed grabs. He was an awkwardly built person, all shoulders and rather stooped. He was unusually tall. He generally resembled shortstop Glenn Wright. In fact, Traynor, Wright and Joe Cronin all played in the Pirate infield at one time, and they all looked somewhat alike as far as size goes. For their day, they were all unusually tall. But to me, Pie Traynor was the finest third baseman I ever saw play. He was a true leader.

E&J: Tell us about the seventh game of the 1925 World Series.

Art: I was ushering at the time. I had the section that Mrs. Walter Johnson was sitting in. She was a nervous wreck. However, Washington jumped in front of the Pirates in the first inning, 4-0. It was raining from the beginning of the game. It was a very light rain, almost a spray. And, it was Johnson’s third start of the Series. Game officials wanted to get this game in. It had been postponed the day before. And as it turned out, the rains fell for quite a while after the last game. The weather turned absolutely sour, and they may not have played the seventh game for another week or so. But the umpires pushed on with Game 7 just to get it in. The Pirates won with a two-out, three-run rally in the eighth inning. It was almost as exciting as the last game of the 1960 World Series here in Pittsburgh.

Washington had some big hitters on that 1925 squad. They had Goose Goslin, Sam Rice, Bucky and Joe Harris, Roger Peckinpaugh and Ossie Bluege. Peckinpaugh was the American League most valuable player that year. However, the Pirates had a very good hitting team of their own that year with a team average over .300. They had four men with over 100 RBIs each.

George Grantham and Stuffy McInnis shared first base. Eddie Moore played second. Wright and Traynor covered the left side of the infield. Clyde Barnhart, Max Carey and Kiki Cuyler manned the outfield with Earl Smith and Johnny Gooch doing the catching.

McInnis had been around baseball forever. I believe he had been in the American League with Boston. Carey had been playing for the Pirates for an awfully long time as well. I think every Pirate starter except Moore hit .300. And, of course, Cuyler was the hero with the hit down the right field line that got entangled in the canvas and drove home the winning runs. An irony in all of this was Joe Harris, who played for Washington in the 1925 World Series, played for Pittsburgh in the 1927 World Series.

E&J: Tell us about the Waners.

Art: Paul came along in 1926. In fact, he asked permission to bring his kid brother to spring training. Of course, that was Lloyd, a second baseman at the time, who replaced Max Carey in center field. Both Waners were singles hitters. They were batting magicians. Paul was an excellent right fielder. He played that strange wall in right at Forbes like you and I eat lunch. In fact, during the early 1950s the Pirates brought Paul back to Pittsburgh to teach Gus Bell to play the wall and Bell resented it for some reason. Bell’s reaction greatly upset Manager Billy Meyer, and Bell did not stay long with the Bucs.

E&J: Did Waner ever transfer any of those right-field tricks to Clemente?

Art: No. Clemente was an absolute natural in everything he did in baseball. He picked up things on his own very quickly. He was a great self-teacher. He told me one time that when he threw homeward to nail runners trying to score, he never threw to the catcher. He threw to the umpire because the ump always positioned himself to see the slide at home. He felt it gave him an advantage because the ump could easily see the ball’s arrival in front of his face.

E&J: Could anyone throw better than Clemente?

Art: No one. But Willie Mays had a throwing arm equal to Clemente’s. Carl Furillo of the Dodgers also had a great throwing arm.

E&J: Let’s get back to your career as the Buc public address announcer.

Art: It was a great experience. I remember introducing Vice President Richard Nixon. That was a great thrill for me. I remember Umpire Ed Sudol taking the time to call me from the field with every change in the 1974 All-Star Game lineup so that I would be correct and on top of things. It was difficult to be involved in a circus like the All-Star Game from the press box and not be connected with anyone down on the field. Sudol was so kind and helpful and I never forgot his assistance. I was very proud of doing both PA announcer and scoreboard operator simultaneously.

E&J: Who was your first Pirate hero?

Art: Babe Adams. I used to catch in for him when he hit fungoes during fielding practice prior to the start of the games. That was the job of the pitchers when they were not pitching that day. Adams would stand to the right of home plate and hit the ball to right and center fields. He would look around for me and call, “Where’s my boy?” I’d run over and catch the throws back to him. In those days I was so proud to be near him. He was the pitching hero of the 1909 World Series, winning three games over the Tigers. He was from the state of Missouri, and he was a very calm and gentle person.

In fact, he had a heartbeat of only 58 beats per minute. He pitched a little in the 1925 World Series. He had a great year in 1921 winning 14 and losing just five. He and Whitey Glazner had great seasons for the Bucs in 1921. They had identical pitching records that year. Glazner, unfortunately, disappeared from baseball shortly thereafter.

E&J: What did you think of the Hall of Famer Arky Vaughan?

Art: He was just about as good a hitter as I ever saw. I do not know why it took so long for him to be voted into the Hall of Fame. He was an excellent hitter and a very good fielder. If he had any fielding problem, it was the slow grounder hit directly at him.

He was a very low-key person. I remember one time when Eddie Stanky of the Dodgers came sliding into second with his spikes a little high, and he nicked Vaughan. Stanky’s hat flew off and Vaughan promptly kicked it into center field. He then told Stanky that he would kick him into center field the next time he came into second base like that. Vaughan was slow to anger, but once riled, he became a very tough kid.

E&J: The destruction of Forbes Field must have been a serious loss to you personally.

Art: Right before the last doubleheader played at Forbes between the Bucs and the Cubs, I told everybody that I was going to stay in the park all night, like sitting up with a dying friend. I just wanted to look over the place for the last time. I really didn’t want to leave. I wanted to hold the hand of my dying friend. That is how I felt.

I grew up at Forbes Field. I had been going there for more than 50 years, and it meant a great deal to me. However, the city needed an all-purpose stadium to house the Steelers in order to keep them here. The Steelers had never had their own field to play on. Seemingly, they were always “borrowing” Forbes Field or Pitt Stadium. I think that is why Three Rivers Stadium is better for viewing football than baseball. But it is plastic to me.

However, when we moved into the place in 1970, it was a joy because the working facilities were far superior to those of Forbes Field. Restaurants and toilet facilities were far better in the new park. The University [of Pittsburgh] had purchased Forbes Field from the Bucs, and just let it run down. Why would they put any money into it? It was scheduled for demolition, plain and simply. By 1970, it was totally tired and rundown.

The major regret I have with Three Rivers Stadium is that center field is not open for viewing the city the way the original plans called for. It would have cost a lot more money to open the stadium in center field than to close it the way they did. That seems strange to me.

E&J: Would real grass make you feel better about the stadium?

Art: No. The Steelers ruined the grounds at Forbes Field every year. They had to re-sod the field every spring. The place always looked like a patch quilt. The Steelers would do the same thing in Three Rivers Stadium. Putting in new sod every year is horribly expensive. Mayor Sophie Masloff had a great idea a few years ago when she suggested a separate baseball park for the Pirates. It was just ill-timed. However, they have it in Kansas City and other places.

E&J: Barney Dreyfuss ran a very tight ship in your early days with the Pirates.

Art: Indeed. In my early days, Dreyfuss, his son and the team treasurer ran the whole thing. They had just a handful of employees. I know it was less than ten. It seems hard to believe. They ran everything. Today, it seems to me that the Pirates have everybody in the world working for them. I see all those names in the press guide, and it staggers me. Wow!

E&J: How would you evaluate Branch Rickey’s tenure with the Bucs?

Art: Rickey wanted young ballplayers in Pittsburgh. He also wanted them married as soon as possible. He wanted them concentrating on baseball and nothing else. He never fulfilled his Pittsburgh ambitions. He had been very successful in both St. Louis and Brooklyn, but not here.

He started farm system baseball in St. Louis, and controlled so many ballplayers that Judge Landis, I believe, had to break it up so that some of them could eventually make it to the majors. As I recall, Rickey was really one of the smartest baseball men ever. But he would not go to the ball park on Sunday. He had promised his mother years before that he would keep the Lord’s Day, and he did. He was well educated, and he lived and spoke the part. Unfortunately, perhaps, he did not stay very long in Pittsburgh.

E&J: If there is anyone who should know this, it is you, Art. Why did the Pirates retire Billy Meyer’s number “1”?

Art: Because the Pirate organization truly loved the man. I have asked a number of people who should know, and they all said the organization was fond of him and always had been. They wanted to do him a special favor.

He had one great season as a Buc manager in 1948. The team was in contention for the pennant up to the final couple weeks. It lost to the Boston Braves with ex-Buc Bob Elliott leading the way. Meyer had Danny Murtaugh playing second and Stan Rojek playing short. Kiner was in left with Wally Westlake in center. Frankie Gustine played third. It was a very good team.

E&J: How well do you remember Dino Restelli?

Art: The greatest flash in the pan ever: 12 homers in 1949. It seemed like he hit them in his first two or three weeks here. Chilly Doyle of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph wrote a story about Restelli later that said he was not as good as his father’s spaghetti. His dad owned a restaurant on the West Coast. Restelli was a lot like Johnny Rizzo, only Rizzo tasted longer. Vince DiMaggio was similar to both. Vince struck out with more style and poetry than any other right-handed batter I ever saw. He was beautiful.

E&J: What about some of the changes that you have seen in the game?

Art: What do you mean? The DH? Things like that? Oh, I dislike the DH. I am a purist. Do not change a thing. I even dislike the turf. However, the locker rooms are much better today. You should have seen the Pirate clubhouse in those early days. It was just like a stable. It had a wooden floor with very large lockers for each player. A man could walk in and out of his locker. There was no carpeting. There was one big table in the middle of the room for cards and other things. The place always smelled of wintergreen. That is all the trainer used to treat the players for any and all ills. That’s all. However, he was not really a trainer. He was really a masseur. The strange thing was that nobody ever went on the disabled list in those days. Not like they do today.

E&J: During your public address days, what was the toughest name or thing to pronounce?

Art: Without a doubt, the name Ed Kranepool. No matter how I did it or tried my best to pronounce it correctly, it always sounded like Ed Kranepoooo. That final “L” was always a problem for me.

E&J: Who were your favorite all-time Pirates?

Art: My two favorites were Max Carey and Dick Groat. Carey walked like his legs were made of springs. He had marvelous legs, and he was very fast. Gosh, he stole better than sixty bases one season. Groat was a terrific money player, both hitting and fielding. I’ll never forget watching Groat one day when he was playing against the Bucs in his waning big league days as a Phillie. He had a severe leg injury at the time, but stayed in the lineup. He was literally playing on one leg when he went into the hole between short and third. He made a backhand stab of a grounder and threw out a runner trying to score at home. At the time I thought that only Dick Groat could have made that play. He was pure guts.

E&J: You mentioned Negro baseball earlier. What do you recall now?

Art: In my early days Negro baseball here was really sandlot baseball. Sometimes those guys would play three games in a day, especially on holidays. They’d play a morning game and an afternoon game. And then they would play a game at Forbes Field after the Pirates finished their contest. I would see those guys so tired sometimes that they would not be wearing their baseball shoes, just slippers. A lot of times they would not take batting practice. They would just take the field and play. They had a lot of excellent players. They had Josh Gibson, Vic Harris, Oscar Charleston and Cool Papa Bell. My scoreboard friend and I would sit on the bench with them when they played at Forbes. We would coordinate the scoreboard for them. My friend and I were the only white people allowed to sit on the bench with the black players.

Cumberland Posey, who ran the Grays, was very nice to me. The Grays would draw crowds of 10 to 12 thousand people a game at Forbes Field. The crowds were mostly black people. They would play teams like the Monarchs and the Lincoln Giants at Forbes Field. They had their stars, and we had ours. They were good, and many of them could and should have played in the majors. There was one weak spot in Negro League baseball, and it was pitching. They did not really have pitching staffs. It seemed like everybody took a turn at pitching. The players were all-purpose players.

E&J: Who was the best player you ever saw?

Art: It is a toss-up between Clemente and Mays. However, my favorite manager of all time is the guy running the Pirates right now, Jim Leyland. The man is a psychologist. He treats people in the same way he wants to be treated, and the players love him. He follows the golden rule. He also plays all of his players, and they love that as well.