An Interview With Roger Angell

This article was written by Richard Johnson

This article was published in The SABR Review of Books

This article was originally published in The SABR Review of Books, Volume III (1988).

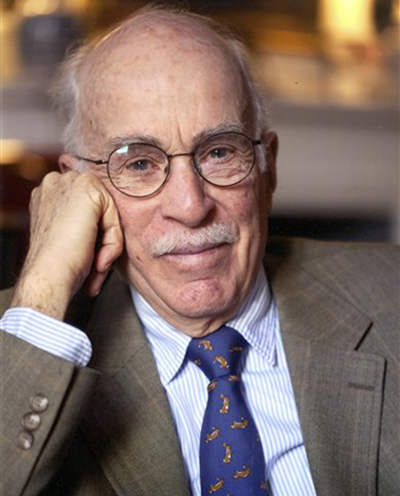

Roger Angell’s office at The New Yorker where he works as senior fiction editor and baseball reporter, has the rumpled busy look of a college professor’s study. Shelves are lined with baseball guides, SABR publications, autographed baseballs, odd wire sculptures of ballplayers and framed photos of a stern Bob Gibson and smiling Garrison Keillor and others. Of special interest were a photo of Yaz leaning heavily against the Green Monster talking, no doubt, to the scoreboard boy, and a hand colored engraving of Bill Campbell in pitching sequence, looking like an antique military manual of arms. I talked with Roger Angell on a gray Friday afternoon in late winter, days before the start of spring training. He poured me a cup of coffee as we began our conversation.

Roger Angell’s office at The New Yorker where he works as senior fiction editor and baseball reporter, has the rumpled busy look of a college professor’s study. Shelves are lined with baseball guides, SABR publications, autographed baseballs, odd wire sculptures of ballplayers and framed photos of a stern Bob Gibson and smiling Garrison Keillor and others. Of special interest were a photo of Yaz leaning heavily against the Green Monster talking, no doubt, to the scoreboard boy, and a hand colored engraving of Bill Campbell in pitching sequence, looking like an antique military manual of arms. I talked with Roger Angell on a gray Friday afternoon in late winter, days before the start of spring training. He poured me a cup of coffee as we began our conversation.

Q. Describe your background as a fan.

A. I grew up in New York as a Yankee and Giant fan, not the Dodgers. They were distant and not very good. I was a big Giant fan, especially for Carl Hubbell and, with the Yankees, for Joe DiMaggio.

My father had put me onto baseball. He had grown up in Cleveland and had been a big Indians fan all his life. I shifted my own loyalties to the Red Sox in the fifties. Being a Yankee fan wasn’t much fun because they won all the time. I spent a lot of time in New England. I went to Harvard, and I had a New England family and saw a lot of Red Sox suffering down east in Maine.

Q. Did you ever aspire to be a sportswriter?

A. I never wanted to be a baseball writer, but I wanted to be a writer. I wrote for more than twenty years — stories, articles, books. Becoming a baseball writer occurred a great deal later, although in many ways I think I am not a baseball writer at all. I’ve never been a beat writer and those are the guys who really know the game. I do something different, not necessarily something better. I admire them and I feel that being fresh, day to day, and continuing relationships with and against players and so forth, is the highest form of baseball journalism.

Q. How do you select the topics and personalities about which you write?

A. I think that the people I’ve chosen are for evident reasons. I did a piece on Dan Quisenberry because he was so unusual in his character and personality, and because relief pitching is such a special part of the game. He is wonderfully articulate and intelligent. I did Bob Gibson because he was just plain fearsome. I realized I was scared of him even after he had left the game, but he was an amazing interview — absolutely open and honest. I find that I do mention many of the same people in my baseball pieces, year after year. My list of baseball friends and acquaintances is growing, but it’s most useful to go to people who are knowledgeable and sound about the game, and who feel confident talking to me. Bill Rigney, for instance. He’s been in baseball all his life, he has a great memory, and a lovely feeling for the game. He’s funny, too. He’s great company.

I am still learning baseball, thank God, and I expect I always will be. I find the best people in the game are always the ones who tell me that they are still learning, too.

Q. Who are some of your baseball friends?

A. Well, Peter Gammons is one of them. I talk baseball with him both to find out what’s going on in the game and to share our passion for it. We often sit together at games. It’s a funny thing — if we’ve been together at a playoff game or a Series game, I will find observations and ideas of his in my writing later on, and I’ve noticed that some of my observations and ideas creep into his pieces. This is fine, I think; we’re friends, and we trust and admire each other. I know I get more from this than he does, because Peter is more in the game than anyone I know. He was a wonderful newspaper writer, back with the Boston Globe; his output was extraordinary.

Ron Fimrite, of Sports Illustrated, is also a close friend. Dave Bush, with the San Francisco Chronicle, is a great baseball friend who will talk long distance for hours. I have friends in New York whom I consider invaluable. There’s the writer Peter Schjeldahl, a poet and art critic. He and his wife are passionate Mets fans. When I wrote about what Mets fans were doing in 1986 they were among those I profiled. There is a poet colleague of mine here at The New Yorker named Alistair Reid, who tells me about baseball in the Dominican Republic, where he lives.

Your question in a larger sense is about baseball as a form of belonging, a form of having friends, a community. It’s a wonderful thing when a team wins for the first time and the fans discover each other. Whole groups of people begin to realize that there are people all around them who have been suffering in the same way over the years and have the same memories of bygone players and teams. This was very evident during last year with the Twins, and I tried to write about that.

I am fortunate because I get a steady flow of baseball mail, letters from people I don’t know. Some of them have become pen pals and even private stringers. They write me about baseball in Seattle and San Diego, but mostly they write about themselves. I think that it’s not stretching a point to say that baseball has filled in for quite some significant areas of life that mean less to us than they once did: our politics, our cities, our families, and our sense of community. I think all these connections are somewhat crumbled in our society while baseball feels very much the same as it always did, at least in the sense that we belong to the game in the same way. It is therapeutic and exciting to have this conversation, which can be conducted almost on a national basis. The other side of this, of which I have written, is the bitterness that you sometimes sense, among the dedicated non-fans — that edge of scorn in a look or a bitter joke which contains a good deal of envy. I think that people who don’t belong to baseball see how much it means to us in a serious sense, and they envy that.

Q. What factors do you think have contributed to the rise in both the quantity and quality of baseball writing?

Q. What factors do you think have contributed to the rise in both the quantity and quality of baseball writing?

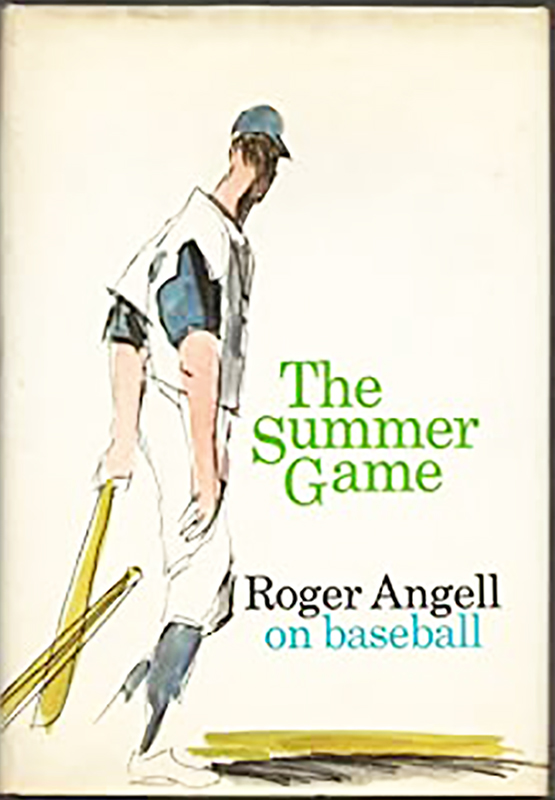

A. Well, I thought all along that baseball was different from other sports, and that some of its special qualities were conducive to good writing. When my first book, The Summer Game, came out in 1977, I went around the country on publicity tours, and most of the TV and radio people I encountered seemed amused and a little scornful that anyone would still want to write about baseball. They felt baseball was all finished, that it was a game watched by old folks and kids. Pro football was very much the king of sports back then.

I don’t feel that way. Baseball is not like our other sports. It uses time in a different way, so it’s difficult to encompass and program on television. We watch too many sporting events on television, I’m afraid. Every weekend, almost every day, there’s an inundation of “championship” events. I think fans have become surfeited with this, and they’ve begun to notice that since baseball is slower, and that it’s played day by day, all through its season, it is pleasing to us in quite another way. Fans and writers have seemed to come to this realization at the same time. Baseball is the perfect writer’s sport: it’s linear, there’s time to take notes, make drawings, and think idle thoughts. In my case, which is probably different from other writers, because of the space I am given, baseball is also a way of writing about myself.

I think, too, a lot of writers who were not sportswriters began to sense that baseball was a way to spread themselves a little bit. It’s very inviting for literary people to seem manly and at home in the world of sports, and all. It’s inviting to be writing about the American Game. Writers want to connect themselves to their childhood and there are easy connections there — to childhood, to fathers and sons, and to the evocations of a simpler past. These things seem very obvious to me.

Of course the deepest lure of any sport may be that it provides us with heroes — people to whom something has happened that’s more difficult than what is happening to us on a given day. We can see them dealing with it or not dealing with it, and both alternatives are seductive to us. This is always visible in baseball, which is both a team game and an individual game, where individuals stand out.

Q. Who would you say are some of the best current baseball authors?

A. Well, there are a lot of them, but I try not to answer this question because I invariably leave someone out.

Let me answer this another way and mention some of my all time favorite baseball books. I would start with Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times, a classic work that opened up the past of baseball for us all. The second edition is also a great and important book, with its wonderful chapter on Hank Greenberg.

Q. What of baseball fiction? I have a friend who theorizes that baseball fiction is so hard to pull off because real baseball is so much better.

A. I wrote that years ago. I find it hard to get involved with it. It’s so hard to create a whole world that could equal what we know about this particular day in the majors. But I thought the first two novels by Mark Harris were excellent. They were something that hadn’t been done before. They were rich and inventive and funny.

Q. Would you say that Ring Lardner was the first baseball novelist with You Know Me, Al?

A. I enjoyed it but I haven’t read it for years. Those days were so different. He was really writing humor about hicks and rubes, when ballplayers were guys with straw suitcases. A lot of the humor in that book is about people not knowing their way around. This isn’t true anymore. Ballplayers catch up very quickly, even if they have come from, say, a backwater in Latin America; after one swing through the league they become dazzling cosmopolitans.

I can remember the players I encountered 25-30 years ago when I first began doing this and I’m certain there is a higher level of education and sophistication, an awareness of the media, and so forth, with today’s player. I also think that the players’ understanding of baseball is a lot better. They have been much better coached and many of them have a greater under standing and appreciation of the game.

Q. Have you found any players that are particularly literary?

A. There are some, but I don’t want to talk about that because it would sound as if I’m saying the other players are dumb. Sure, I’ve met players who talk about books, who read.

Let me say this another way. There are guys in the game who talk wonderfully about baseball and I go to them again and again, because as a reporter I’d be stupid not to. Also, I learn. When I did the long piece about catching for my new book I had the impression that catchers knew enormous amounts about baseball. They seemed further into the game than other players. They were a wonderful group to talk with. Most of what catchers do is overlooked and they love to talk about what they do and their relationship with pitchers, umpires, hitters. The whole game is in front of them. Among them you find people like Ted Simmons, Bob Boone (a brilliant conversationalist about baseball), and Carlton Fisk. As a reporter in any field you would always go back to the best talkers. This brings up another subject that has always interested me — the fact that the most interesting players to talk to are usually the older players. They have all gone through the process of changing from young stars, who didn’t really understand how the game was played because of their enormous inherent talent. When those skills begin to leave them they have to learn the responses and actions they have been using by instinct, and that’s when they begin to think about the game. At that point some of them become fans for the first time. There are a lot of ballplayers out there who play the game wonderfully but don’t really care. It’s just another sport to them, because they were also great football and basketball players and chose baseball.

I did a piece about hitting in Late Innings, and in it I mentioned older players who told me that they wished they had known as much about hitting when they were beginning as they had learned at the end of their careers. Others said that just at the time they learned the game they had to leave it. That’s interesting, and you can usually get a veteran’s attention when you discuss the intricacies of baseball. Younger players aren’t that involved.

Q. What elements of the game do you miss that were there when you first started to write about the game?

A. I miss daytime ball, now a rarity, and daytime World Series games, a terrible loss. I miss some of the old ballparks. More will be gone soon. Tiger Stadium is probably going to go, Comiskey Park, too. I miss grass. Grass is still infinitely preferable than artificial turf. I miss that play behind second base where the shortstop can just get to a ball with the last half-inch of his grasp and pick up a slow bouncer and throw out the runner at first. That’s a beautiful play that’s just about gone on an artificial surface. I’ve written about what we’ve lost and what we’re losing but I don’t think about baseball with a catch in my throat. I don’t have sentimental thoughts about the grand old game. I resent some of the changes, I am wary of others that I think are going to come’ but so far the game is played just about the way it always has been.

Q. Which baseball figures of the past would you have wanted to meet and write about?

A. Just the obvious ones. I don’t think I have any great insights on players of the past that most fans don’t already share. I would have loved to have seen Cobb play; I saw Ruth quite a bit; I also would have enjoyed seeing Walter Johnson, and Christy Mathewson. But I don’t think about the baseball past that much. I think that the absence of a dominant team is something that some fans miss a lot. I can’t decide if this is a good thing or a bad thing. We haven’t had a repeater in the playoffs in this decade or a repeater in the Series since the seventies. It’s always fun to have a dominant team during a decade and see other people try to knock it off.

The seventies had the Oakland A’s and the Cincinnati Reds as the two great teams of that decade, with the Yankees not quite reaching that level at the end. I think that older fans look back to the old Yankees with longing and I’m not so sure that’s justified. The Yankees so dominated baseball that we thought of them in the same terms as imperial Rome. But the way they won was by beating up on teams in the second division. I wrote this down the other day (produces a notepad from his desk), and it’s an amazing stat. If you count the season series against the four second-division clubs in the American League — namely the White Sox, Browns, Senators, and Athletics from 1930 to 1959 — and then see how many season series each of these teams won against the Yankees in that span, the Browns won two, the Senators won two, and the White Sox and Athletics each won one: This means that over a thirty-year period, the composite season series record has the Yankees winning one hundred and fourteen and losing six. That’s pathetic.

The economy of baseball, at least in the American League, meant that these teams balanced their budgets, year after year, with two or three sellout home games against the Yankees. This is how the lesser teams would break even.

I think we are in better shape with more equal competition. I am sympathetic to the long suffering fans of the old franchises. I think Cub fans are the best there are, anywhere. They will turn out in enormous numbers even if the team is going nowhere, and their feel for the nature of baseball is exactly right. They are highly critical and they always know why the team isn’t doing well. I’ve heard team owners and front office people say that they wish they had the Cub fans. But you want to see people like that rewarded. I remember when the Padres won in 1984, I was a little hard on the San Diego fans because they really hadn’t been involved. They had never finished above fourth place, and regular season games were like exhibition games for them.

Q. Why do the Red Sox inspire such literary output?

A. Everyone is aware of the Calvinist nature, that sense of foreboding that attaches itself to the Red Sox. The Red Sox have become chic, when they made the Series several years ago the Boston Globe put together a literary supplement on the team. Fans are fans, but the intelligentsia probably aren’t quite the same as the regular fans, the dyed-in-the-wool Sox fans.

Q. I have a feeling that this year we have finally begun to forget about the troubles in baseball. Is this true?

A. I think everyone is tired of this stuff, but the collusion issue isn’t over yet, we’re waiting for the next ruling. The economic penalties on this issue have yet to be determined.

The drug issue has been diminished because people realize that when you have six hundred-plus young men traveling around with a lot of money and not much experience, then drugs will be part of the scene. Drugs are an American problem and sports will have its degree of people with a drug problem. I think there is less of the notion — and this will be a great step forward if it is true — that ballplayers have to be role models. That asks too much of athletes. If we can’t think of better role models for our children than athletes, we’re not doing very well by our kids.

There may a strike in our future because all sorts of unresolved issues are welling up. For example, there is no serious drug testing plan now in place. The old plan worked pretty well and the Commissioner did away with it.

Q. What would you say is the greatest potential threat to baseball?

A. I think it’s expansion. If they want to go up two more teams in order to make the National League equal to the American than that would seem acceptable. A massive expansion would dilute the game terribly.

If that happens we could also walk into another tier of playoff games, and that would damage baseball very seriously. It would do away with the significance of the daily schedule, where every game matters. If you divide the teams into three leagues and look at the records of the four teams in a possible playoff in this configuration, what you find is pathetic. The whole season will be played just to eliminate a few bad teams, the way it’s done in hockey. Baseball would lose much of its appeal if the day-to-day were rendered next to meaningless.

Q. If you could go to three games this year which would they be?

A. I am delighted that I could not possibly answer that question. If you ask me on the first of July I might have a better idea.

I know I’ll be interested to see how the Blue Jays bounce back. I think fans were rough on them, forgetting that they lost two front-line players in [Tony] Fernandez and [Ernie] Whitt the final week of the season. The A’s and the Mariners will be fun to watch. The Red Sox will be interesting with all their young talent and the Yankees have added everything but pitching. The Mets have seven starters, probably too many.

Q. For a while I know you wrote film reviews for The New Yorker. Do you think there are any great baseball films?

A. The challenge is to make a movie look like a ballgame and to put people out there who can throw and run a little bit. I remember seeing Gary Cooper playing Lou Gehrig, which was hilarious. None of the guys in that movie could throw. They now have actors who make a reasonable try at the game. You have the same problems with baseball films as with baseball fiction. I was disappointed that they changed the end of The Natural. This is an interesting novel, intertwining baseball and the King Arthur legend. The film had some beautifully shot scenes, but it made no sense, so they had to lay on the slow motion and fireworks at the end. I think that if you make a good movie with baseball in it, you’re fine, but if you go out to make a baseball movie, you’re in trouble.

Q. Have you ever cheered in the press box?

A. Oh, sure. I’ve been in press boxes where there has been a lot of cheering. The regular writers pretend that they’re above this sort of thing, but they don’t fool anyone.

Q. Has SABRmetrics been overdone?

A. I don’t think it’s an issue. Overdone for whom? Some people love this stuff. It’s an addition to the game, it’s a different way of looking at it. I don’t think it changes how the game is played. I don’t think the front offices use SABRmetrics. I think Bill James’ stuff and SABRmetrics is a lot of fun, but it doesn’t mean much to me because I’m not mathematically minded. I’m amused by this stuff and I read Bill James with awe, but it doesn’t change how I think about the game.

Q. Do you find it sad to see so many of our baseball heroes going to shopping malls and selling their autographs?

A. I find it very sad. I think that this is one of the great arguments for increased pension benefits for older players. There is a good organization which includes Ralph Branca that assists former players in need.

In many ways I’m not happy at Old Timers’ Games. The players enjoy it, they have a big laugh, but I don’t like to see someone whom I remember as a great outfielder hobbling along to beat out a nubbed roller. We know they’re old now, but seeing them as they are now interferes with our memory of what they were in their youth. It’s warming to see them, but it’s embarrassing.

We want to make an exhibition out of everything, we want everything to be immediately accessible, but some things are better left to memory and imagination.

The instant replay is great for understanding but it diminishes the moment. You see a great play and you jump up and say, “WOW!” and you can’t get over it. But you see it on replay and you say, “Oh, that’s how it happened” and you see it a third time and it’s become only interesting. The wonder of it, the brilliance has gone out of it.

Q. Were you disappointed when you moved from your perch in the grandstand to the field and met your heroes?

A. Sure, absolutely, but I don’t wish it otherwise. I’m a reporter. Some people say that I’m a poet or an essay writer, but I view myself as a reporter. Reporters learn the truth about people. I’m a grown-up, and I don’t care if a great ballplayer is not a great guy. We go to a game to see what these guys do, or don’t do out on the field. What they’re like in the clubhouse, how they treat their wives or how they think about Nicaragua are totally beside the point and usually not very interesting. We sometimes forget what we came for. People become so famous that we want to be close to them and know everything about them. We want their fame rather than what they can do. Reggie [Jackson] played the press like a Stradivarius and understood all this. He was a natural showman. He also drove me crazy, like everyone else, but I believe that Reggie operated under more self-imposed pressure than any player I’ve ever seen. Those three home runs in the ’77 Series was the greatest baseball feat I’ve witnessed. His persona has eclipsed what he was as a player and that is a loss. It’s too bad.

Q. What constructive things can SABR do for baseball?

A. I think that the way for SABR to be most effective would be to try to enroll all the significant front office people and deluge them with material. They should be more aware of the existence of the people of SABR and their care for the game. I think the Ballparks Committee is great, but I would be surprised if any owner really paid close attention to the committee when he was getting ready to build a new ballpark. And they should. There is no reason why baseball can’t build a modern Wrigley Field or Fenway Park, a jewel with all the charm of the parks built in 1912, and the modern amenities as well.

But I don’t think most owners think like this or think about these possibilities. If the Giants had won the right to build that new downtown ballpark I’m not sure if Bob Lurie would have listened to people with strong feelings about baseball. Owners think they own the game when all they own is a franchise. The fans are really the owners of the game.