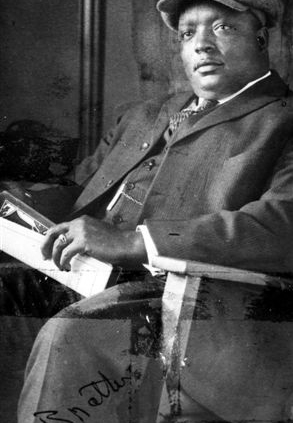

Andrew (Rube) Foster: Gem of a Man

This article was written by Larry Lester

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (2021)

Editor’s note: This article is updated from the original, published in SABR’s “The Negro Leagues Book,” 1994.

Andrew Bishop Foster

- Bat/Throw: Right/Right—5’9”, 235 lbs.

- Born: Wednesday, 17 September 1879, La Grange, TX1

- Died: Tuesday, 9 December 1930, Kankakee, IL

- Cemetery: Lincoln Cemetery, Section 6, Latitude: N 41º 40’ 15.7”, Longitude W 87º 42’ 04.9”, Blue Island, IL

- Hall of Fames:

1981 COOPERSTOWN HALL OF FAME

1998 TEXAS SPORTS HALL OF FAME

2004 TEXAS BASEBALL HALL OF FAME

Folks who knew Rube called him a pitcher, a cheater, a ticket taker, a popcorn maker, a show maker, a showstopper, a money maker and, of course, a game breaker. He could do it all. The ultimate baseball attraction in one package—this was Rube Foster.

Folks who knew Rube called him a pitcher, a cheater, a ticket taker, a popcorn maker, a show maker, a showstopper, a money maker and, of course, a game breaker. He could do it all. The ultimate baseball attraction in one package—this was Rube Foster.

Reared in Texas by a preaching father and a gospel-singing mother, Foster disobeyed his parents to pursue a career between the white foul lines. He had the God-given ability to organize and promote teams, but much credit goes to Frank Leland, a product of Fisk University, who tutored a young Rube to immortal stardom.

Young Rube’s vision began in 1897 with the Austin (TX) Reds of Tillotson College (now Huston-Tillotson University). The following year, he joined the semi-pro Yellowjackets in nearby Waco. Here, he developed a nasty screwball thrown from his unique submarine delivery. Entering the new century Foster signs with Frank Leland’s Chicago Union Giants for $40 a month and 15 cents a day for meal money.

In 1903, Foster headed East to play for the Cuban X-Giants. That fall, he posted four victories in a seven-game series against the Philadelphia Giants for the so-called “Colored Championship of the World.” After joining Lamar’s Cuban X-Giants, Andrew Foster’s reputation as a fine pitcher expanded with a victory over Major League’s top southpaw ace Rube Waddell in 1903, while leading the league with 34 complete games that season. Nat Strong, manager of the Murray Hills, a midtown Manhattan semi-pro team, recruited Waddell to pitch against Lamar’s Cuban X-Giants on blue Sunday. The classic duel at Olympia Field between Foster and Waddell saw the X-Giants excel 6-3 with both pitchers going the distance. A tired rubber-armed Waddell, listed in the New York Sun (August 3, page 6) as “Wilson” in the line score gave up 11 hits, and Foster yielded seven hits. Both pitchers worked without their regular catchers; Waddell with O’Neil, and Foster with Big Bill Smith, normally an outfielder for the X-Giants.

The wandering Foster switched over to the Philly team the next season, 1904, and re-encountered his old teammates for bragging rights to the “colored” title. Foster accounted for both victories in the best-of-three series. He struck out 18 batters in one game, beating the current major league record of 15 set by Fred Glade of the St. Louis Browns.

In 1907, he returned to Chicago and joined the Leland Giants, leading them to a 110-10 won-lost record, including 48 straight wins. In 1909, the Giants entered the tough integrated city league. In Foster’s first eleven starts, he won eleven games, with four shutouts. Such a dominating force that season, after one commanding victory an Indianapolis Freeman newspaper’s headlines simply stated: “FOSTER PITCHED, THAT’S ALL” with no box score listed.

By 1910, the Leland Giants were the chatter of every clubhouse. They christened a ballpark in an all-White neighborhood near 69th and Halsted, as the Leland Giants Base Ball Park. Foster now serving as player-manager, amassed in his opinion the greatest team of all time. Featuring such stars as John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, the notorious streak hitter Pete Hill, Grant “Home Run” Johnson, catcher extraordinaire Bruce Petway and great pitchers like Frank Wickware and Pat Dougherty, the Leland team won 123 of 129 games. This team compelled John McGraw of N.Y. Giants fame to announce, “If I had a bucket of whitewash that wouldn’t wash off, you wouldn’t have five players left tomorrow.”

The following season, Foster formed a partnership with John Schorling, a White businessman. Together they purchased Old Roman’s, a ballpark at 39th and Wentworth, from White Sox owner Charlie Comiskey. The park became home of Black baseball’s finest team, the Chicago American Giants. Foster billed his team as “THE GREATEST AGGREGATION OF COLORED BASEBALL PLAYERS IN THE WORLD.” The Giants normally played semi-pro teams for a guarantee of $60, rain or shine, with fifty percent of the gross receipts guaranteed if their ace, Rube Foster would pitch.

Although an outstanding pitcher, a dependable team owner and a brilliant manager, perhaps Rube Foster’s most impressive fulfillment came with the creation of the Negro National League of Colored Base Ball Professionals, better known as the Negro National League (NNL). It consisted of eight ships of hope to battle the sea of racism. The league’s motto was “We Are the Ship, All Else the Sea.” Going against the tide of segregation, Rube’s voyage would become an obsession. Foster, the genetic Eve of Black baseball, birthed a confederacy of clubs that embraced a permanent existence of quality baseball. It became the first league of color to survive a full season. For years, Captain Rube struggled without a life preserver in his attempts to keep his boat afloat.

From his throne in Chicago, Foster ran the NNL as a noble emperor. He realized the need for balance competition, as he moved players from team to team, even sending his American Giant star Oscar Charleston to the Indianapolis ABCs. He often lent money to failing franchises to help meet its payroll and advanced monies to his own players. With unparalleled influence, Foster was the undisputed kingpin of Black baseball in the Midwest.

With brains and influence, Rolodex Rube seemed invincible. In 1926, the czar-like dictator, with the booming baritone-voiced, succumbed to mental illness and was institutionalized in Kankakee, Illinois. One of baseball’s greatest minds was suddenly torn from the game. Four years later, the son of Sarah Watts and Rev. Andrew Foster, Sr., was buried in Lincoln Cemetery near Chicago.

Foster, with his dedicated, high-minded approach to baseball, was the force behind all subsequent major Negro Leagues. In November of 1930, renowned sportswriter Frank “Fay” Young, for Abbott’s Monthly, testified on behalf of the late legend, “One of the most brilliant figures that the great national sport has ever produced. Rube knew every technicality of the game, how to play it, and how to make his men play it. A true master of the game.”

Foster redefined the art of base running, hit and run techniques, and the do-or-die sacrifice play. He used creative ways to ‘stretch’ a hit, to ‘steal’ a run and eventually ‘swipe’ a victory. In 1981, justice was served as Foster was found guilty of larceny and sentenced to a life term, without parole, into Cooperstown’s Baseball Hall of Fame.

Overall, his life history was a real page-turner. Rube was a phenomenal pitcher, a magnificent manager, a powerful organizer and even greater humanitarian. He had the face of a Koala bear, the heart of laborer John Henry, the smile of Billy Dee Williams, the essence of Malcolm X, the vision of Dr. Martin Luther King, the oratorical skills of James Earl Jones with the creative genius of Ray Charles. Rube Foster was the most robust blend of baseball expertise ever assembled.

LARRY LESTER is co-founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and serves as chairman of SABR’s Negro League Research Committee. Since 1998, he has organized the annual Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference, the only scholarly symposium devoted exclusively to Black Baseball. He is the author of Rube Foster in His Time, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933–1953, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs, and The Negro Leagues Book (with Dick Clark), which has been updated in a second volume (with Wayne Stivers) available on Kindle. Lester lives in Raytown, Missouri. Lester is winner of the 2016 Henry Chadwick and 2017 Bob Davids awards.

Notes

1 The 1880 Census shows the Foster family living on the McKinny plantation in Winchester, Fayette County, Texas. An eight-month old Andrew Bishop is listed with his father, mother, one brother and two sisters. Land deed records suggest the Foster family lived as cotton sharecroppers for widower J.L.T. McKinny and his son Edgar on the southeastern side of Winchester, about 18 miles northwest of La Grange. The 1900 Census (the 1890 Census was mostly destroyed by fire in 1921) shows the family living in Calvert, Texas, the most commonly cited birthplace for Andrew Bishop Foster.