Aspect of Nemesis: A Look at the Phenomenon of ‘Killer’ Pitchers

This article was written by Zita Carno

This article was published in 2001 Baseball Research Journal

You know the names: Mathewson, Johnson, Alexander, Grove, Hubbell, Ruffing, Gomez, Newhouser, Feller, Chandler, Brecheen, Trucks, Raschi, Lopat, Spahn, Maglie, Maddux, Marichal, Glavine, Martinez, Clemens, Wells …

They and many others throughout the history of the game were, and are, also known by other names: killers, jinxes, hexes, hoodoos, voodoos, and the entire gamut of unprintable epithets. They were, and are, accused of black magic, sorcery, witchcraft, alliance with the devil, and conspiracy with Macbeth’s three witches. They were, and are, aspects of Nemesis.

In the ancient Greek mythology, Nemesis was the goddess of retributive justice. In time her name became synonymous with one who destroys inevitably and relentlessly, and from there it was only a short step to the meaning of the term in modern baseball: a pitcher who repeatedly, consistently and with almost monotonous regularity defeats certain teams as if he owns them. A killer.

To list every pitcher who has ever functioned thus would require volumes, so let’s go with some representative examples. But first, let’s consider what makes a pitcher a killer.

Simply put, such a pitcher is extraordinarily effective against a certain team — or, in some cases, more than one team — over a period of time, usually with a percentage of .600 or better. There have been instances of pitchers who did this for a year or two and then stopped, either because they were traded out of the league or because their patsies caught on to them. Walter “Monk” Dubiel, for example, who pitched for the New York Yankees in 1945 and 1946, racked up an 8-2 record against the Boston Red Sox before disappearing into the minor leagues. Also with the Yankees was Ernie Bonham, who over a period of seven years went 15-6 against the Cleveland Indians before being traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates at the end of the 1946 season. Detroit Tigers hurler Hal Newhouser, who beat the Yankees six times in 1943 without a defeat, never again exhibited quite that level of mastery, even though he gave them a lot of trouble in subsequent years.

For the most part, however, such pitchers continue to build up winning records against particular opponents over long periods of time, sometimes with devastating psychological results. Let’s consider a few of them.

In the beginning

The first recorded instances of pitchers being labeled “killers” occurred in 1908, both in the National League. In July and August of that year the Chicago Cubs’ Jack Pfiester won crucial games against the New York Giants, leading sportswriters to call him — what else? — “Jack the Giant Killer.” Then, during the final week of the season, the Philadelphia Phillies’ Harry Coveleski defeated the Giants three times, thus also earning the nickname, “Giant Killer.” (This feat was virtually duplicated in the 1957 World Series by Lew Burdette who defeated the Yankees three times, two of them shutouts.)

In the early days of the game pitchers worked every two or three days, even working both ends of doubleheaders, and the best of them compiled good records against all comers. Even then there would be one team, maybe two, these aces would beat more regularly than the rest. Look at Babe Ruth — he went 17-5 against the Yankees before they got him. And Walter Johnson, who beat everybody, was most effective against the White Sox, the Tigers, and the Highlanders/Yankees. His 66-42 record against Detroit still stands as the most lifetime victories by an American League pitcher against one club.

In the National League, the record-holder in this department is Grover Cleveland Alexander, with a 70-24 lifetime record against the Cincinnati Reds. Christy Mathewson is not far behind, at 52-24 versus the St. Louis Cardinals and 64-18 against Cincinnati. The most startling record of the era, in either league, belongs to Carl Mays, who during his career with first the Red Sox and then the Yankees racked up a 35-3 (.921) record against the Philadelphia Athletics.

The winds of change

In the 1920s, the ball was livelier, home runs were more common, the spitball and other such pitches were outlawed, and hurlers were forced to find other ammunition. George Blaeholder and George Uhle both came up with the slider, and Red Ruffing refined the pitch and made it a staple in the repertoire of almost every hurler. There still were some pitchers who beat everybody, but more who displayed a wider range of “killer” records and percentages. Take the case of Lefty Grove, who was a Red Sox killer from 1925 through 1933 with a 35-8 record against Boston. He didn’t do too badly against the Tigers, either, compiling a lifetime record of 39-19. But at the other end of the spectrum we see 31-25 against the Senators and 34-27 versus the Yankees.

Pitchers began to take more time between starts. The era of the relief ace was just around the corner. It took a pitcher longer to build up the kind of record against a team that would earn him the title of Nemesis. And there were trades: on occasion a pitcher who had been beating a certain team to a pulp would end up being traded to his patsy. Grove, who stifled the Red Sox for nine years with Philadelphia, was traded to the Sox and could manage only a 13-5 record against his old team, although he continued to defeat the Detroit Tigers.

The Age of Nemesis

From the 1930s through the 1960s, there were many Nemeses in both leagues. As usual, the great power pitchers were highly successful, but during these years, many finesse hurlers relied on good stuff, accurate control, and brains to enjoy equal success against their chosen victims. In fact, they may have been the deadliest of the lot. I will discuss one in particular later on, because the devastating effect he had on his favorite patsies constituted an extreme case.

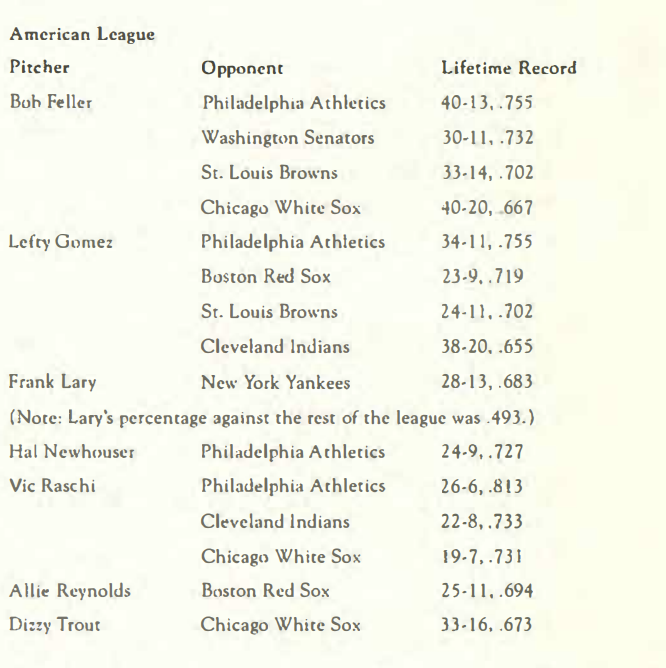

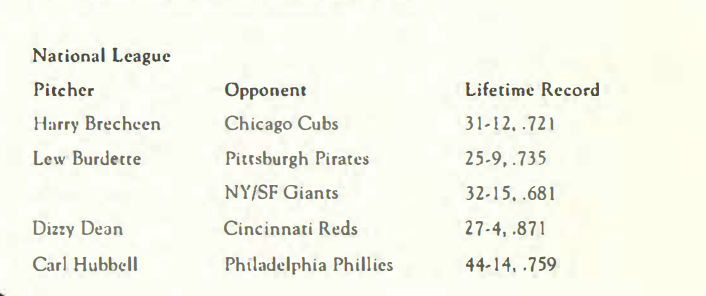

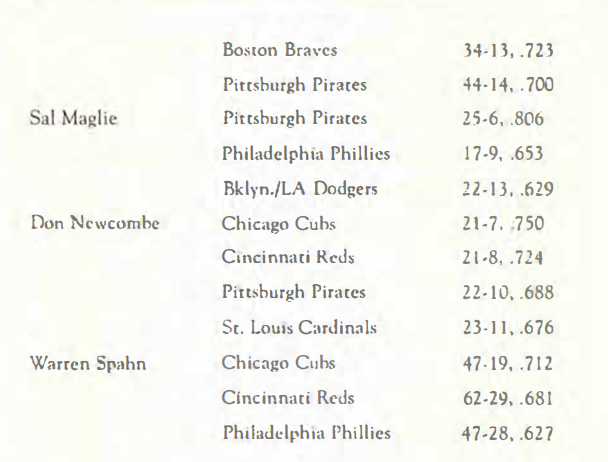

Several teams were especially beloved of these “killer” pitchers. In the American League the teams they loved to beat were the Philadelphia Athletics, the St. Louis Browns and the Washington Senators, while in the National League the overwhelming favorites were the Chicago Cubs, followed by the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Cincinnati Reds. Let’s Look at a few examples.

There were, of course, many others. There was also at least one study in frustration: Mel Harder, the great Cleveland Indians pitcher, defeated the Yankees 25 times-and was beaten by them 25 times, for a grand total of .500. The same thing happened to Bob Feller. Now to the National League.

Later on, Juan Marichal of the San Francisco Giants became a great Dodger killer: 37-18, .673. Question: Is there any particular kind of pitcher who is more likely to be a killer? The answer is no. In this sampling of aspects of Nemesis, we find a nice variety. There are the power pitchers, such as Feller, Newcombe, and Raschi. There are the finesse pitchers such as Brecheen. And then we have the “everything bagel” pitchers like Gomez, Reynolds, and Spahn. We have pitchers who zero in on the contenders, pitchers who pick on the lesser lights of the league, and the pitchers who don’t discriminate — they get on everybody and beat them to a pulp.

Killer Psychology

There’s an old saw in baseball that states unequivocally that all it takes to beat a certain team is for a certain pitcher co throw his glove onto the field.

The morning of a crucial doubleheader finds the Cleveland Indians perusing the paper to see who their mound opponents will be, and what do they find? The starters for the other team are two pitchers who have been waxing them all season. Or just before a night game the Houston Astros learn that Tom Glavine has been scratched because of the flu, and who will take the mound instead? Greg Maddux, who has a 24-9 record against them. Either way, the result is the same: “Oh, no, not again!” or “We’ve had it!” or most likely — a string of undeleted expletives, imprecations, invectives, or just plain cusswords.

Why is this? Why does the mere mention of a certain pitcher throw such apprehension into the hearts of a particular team chat they are thoroughly convinced the game is over before it has even started and they might as well take their equipment and go home? We may never have the complete and final answer co chat question-even the pitchers themselves are at a loss for words-but it may help to look at some psychological angles. Specifically, let’s examine three.

The first is known simply as the law of reversed effect, which states that the harder you try to do something the harder it gets. Case in point: the hitter in a slump. No matter what he does, he just can’t buy a base hit. He goes 0-for-15, then 0-for-25, then 0-for-30. He’s tried everything from a change of stance to a lighter ( or heavier) bat to sticking pins in a voodoo doll-nothing seems to help. When does the slump end? Usually when the batter stops struggling and just tries to lay the bat on the ball. Athletes function best when they just do what they do.

Next is the concept of the self-fulfilling prophecy, essentially a matter of supreme confidence, or the lack of it. On the positive side, a pitcher decides he can and will beat a particular team silly. He convinces himself he’s going to do it. And he goes out and does it. The Brooklyn Dodgers had been eating left-handers for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and the Boston Braves had not even sent Warren Spahn out to face them. It was assumed that the situation would stay the same in the 1953 World Series. But Ed Lopat had other plans. He decided he was going to beat the Dodgers in the Series, and what was more, he was going to go nine innings to do it. And in the second game he did exactly that, 4-2.

The third psychological factor is known as learned helplessness, at once a separate and distinct entity and one that incorporates elements of the ocher two. Earlier in the twentieth century, a group of psychologists ran a series of experiments on laboratory rats in which they first subjected them to a series of shocks and ocher unpleasantnesses, then taught them how to escape them. Then they repeatedly thwarted, stymied, blocked the rats’ efforts to escape. After a while the rats simply gave up. The psychologists then reasoned that the same could be applied to humans.

And so we come to the situation regarding certain teams and their inability to beat certain pitchers.

Jim Brosnan, in his book Pennant Race, describes the Reds’ effort to battle a losing streak: “The momentum of losing a series of games creates a mental force against which a superhuman effort seems called for.” But he fails to mention what happens when the superhuman effort is constantly stymied. For this we need to ask the pitchers involved how they do it, how they beat these teams so consistently — and we get as many answers as there are pitchers. Some don’t know. Others say simply chat they feel they have to do their best against certain teams, such as Frank Lary who racked up a 28-13 lifetime record against the Yankees. Still others take a scientific approach.

One of the last-named is the special case I mentioned earlier. All three elements combined in his success against one particular team.

An extreme case

On September 23, 1949, the Cleveland Indians held a bizarre ceremony at Municipal Stadium prior to their game against Detroit. It was a funeral rite in which they took down their 1948 American League and World Series flags and the crown that had rested atop the image of Chief Wahoo, proceeded to deep center field, and buried these items along with their pennant hopes. Just three days earlier they had been eliminated from the race. Then they went out and lost the game, 5-0.

Perhaps the most puzzled spectator at this eerie event was Cleveland News sports columnist Ed McAuley. He expressed this bewilderment in a long article which appeared in The Sporting News on October 5, coincidentally the opening day of the World Series. He called it a post-mortem, an attempt to determine just why the team, only one year after their glorious Series triumph, had finished an ignominious third.

What had happened to them?

McAuley began with this inescapable conclusion: the Indians had given up.

They had, he said, lost the will and the desire to win. He then explored some possible reasons for this. He cited such factors as the season-long plague of injuries which had decimated the pitching staff and much of the team, reports of dissension within the team, frequent and vehement clashes between shortstop-manager Lou Boudreau and owner Bill Veeck, rumors that some of the players had taken to excessive drinking, and a number of other possibilities. But McAuley omitted one major element, perhaps because it had never occurred to him.

Nemesis.

Ed Lopat was a heavy-set strawberry-blond lefthander who came up to the Chicago White Sox in 1944 and immediately zeroed in on the Indians, beating them, 2-1, in his first start against them. He continued to beat them with such consistency and such monotonous regularity that within a short time he became the one pitcher they feared more than any other in the league. In 1948, just before the start of spring training, he was traded to the New York Yankees, and by the end of the 1949 season he held a 22-6 record against the Indians and was well into a winning streak — his second — that would not be stopped until the middle of the 1951 season.

The situation had gone far beyond throwing the glove onto the field. All that was needed was for the Indians to know that they would be facing him; the only times they escaped were when his turn did not come up in the rotation. They had become thoroughly convinced that they could not beat him for sour apples, and most of the time they could not, as his eventual 40-13 lifetime record against them clearly demonstrates. They had indeed given up.

Stories and rumors about him were making the rounds: Ed Lopat practiced sorcery and witchcraft; he dabbled in black magic; he consorted with Macbeth’s three witches; he supped with the devil. The word was chat he held some arcane, irresistible power over the team. And it wasn’t only the team that was affected; the fans, the sportswriters and ultimately the entire city were caught in the trap from which the only escape would come when he retired after the 1955 season.

In face, Lopat’s irresistible power over the Tribe had nothing to do with black magic or witchcraft; they were especially vulnerable co his kind of pitching. He was one of the greatest strategic pitchers in the history of the game — a finesse pitcher of the highest order who knew how to compensate for lack of speed with a bewildering assortment of breaking stuff, an even more bewildering assortment of ways and speeds with which to throw all those breaking pitches, and accurate, pinpoint control that led observers co state that he was wild if he walked more ch.an two in a game. He was particularly adept at keeping batters off balance, disorienting them, messing up their timing and their thinking, and getting them to go after the pitches he wanted them to hit; they would complain repeatedly chat after facing him in a game they couldn’t get their timing back for a week.

Lopat had an easy, deceptive, almost hypnotic motion which made matters even worse for opposing hitters who found themselves watching and going after it instead of the ball, and there was about him an almost preternatural calmness. Nothing fazed him, not even the events of the June 4, 1951, “Night of the Rabbit’s Foot” when his eleven-game winning streak ended before a crowd of rabbit-foot toting Cleveland fans after one Indian rooter had tossed a kitten at him during his warmups. (See “The Night the Indians Rabbit-Punched the Yankees,” Lenore Scoaks, TNP 94: 45-46.)

Two examples of Lopat’s consistency in bearing the Indians come co mind here. In June, 1950, on a hot day in Cleveland, he left the hotel for some air and something cold him to get down to the ballpark because the Indians might be up to something. He sneaked into the stadium and watched as Sam Zoldak pitched a special batting practice to the Indians in which they practiced hitting slow breaking stuff. That night before the game Lopat took Casey Stengel and Yogi Berra aside, cold them what he’d seen, and said “I think we’ll have some fun tonight.” The game began, and for the first three innings all the Indians saw from him were fast balls and hard sliders, during which they broke several bats. When they switched back to their free-swinging ways, he went back to control-pitching, and only two runners made it to second. He shut them out, 7-0, on six hits.

A little over a year later he outpitched Bob Lemon, 2-1, the Yankees’ winning run scoring on a suicide squeeze play by Phil Rizzuto that scored Joe DiMaggio from third and caused Lemon to grab both his glove and the ball and hurl them full force into the backstop screen, as well as netting Lopat his 20th win of the season.

The irony of it all was that the Indians could have had him. They could have purchased his contract from Little Rock at the end of the 1943 season; instead, they chose to believe their scouts who said he’d never make it in the majors because he did not have a fastball. That decision came back to haunt them for twelve years.

What next?

Ed Lopat was not the only Nemesis who made life miserable for the Cleveland Indians. In 1947 he was joined by Vic Raschi, who would become his teammate the following year and who ended up with a 22-8 lifetime record against Cleveland. Raschi did not stop there; he was 26-6 against the Philadelphia Athletics and also racked up a 19-7 record against the Chicago White Sox.

Since 1970 or so we’ve entered a new era of aspects of Nemesis. We simply don’t see much of this any more. There have been a number of changes in the game: expansion; the business of pitch counts; and the use of specialist relievers. There aren’t as many twenty-game winners as there used to be, let alone true killers. But there are some pitchers who have compiled records sufficient before the 2001 season to earn them the title of Nemesis — or Nemesis-in-the making.

Jim Palmer: over a period of nineteen years, 30-15, .667 vs. New York. Chuck Finley: known as the Yankee-killer, 16-9, .640, but with an even better record against the Seattle Mariners, 19-7, .731. Roger Clemens: 26-8, .765 against the Angels. Terry Mulholland: with Phillies and then Braves, 17-5, .773 vs. Expos. Ramiro Mendoza: 6-0, 1.000 vs. Indians.

David Cone: 18-7, .720 against the Kansas City Royals. David Wells: 14-8, .636 vs. the Yankees; 13-3, .812 vs. the Indians. Tom Glavine: 19-8, .704 against the Phillies; 14-5, .737 vs. the Mets. Greg Maddux: 24-9, .727 vs. the Astros. Pedro Martinez: 9-1, .900 against Indians.

There will be more to come. Let’s await developments.