Astrodome as the Home to Sports Other Than Baseball

This article was written by Alan Reifman

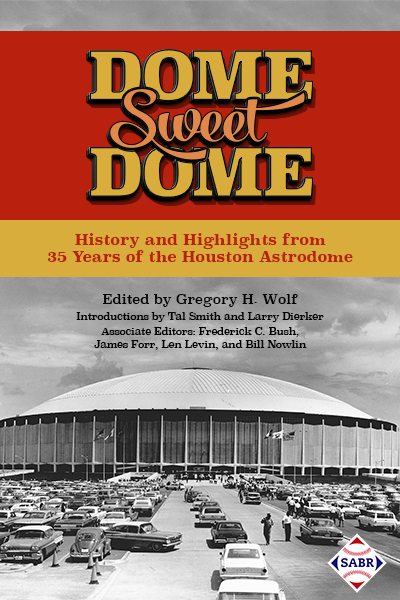

This article was published in Dome Sweet Dome: History and Highlights from 35 Years of the Houston Astrodome

Like other circular-shaped, multipurpose stadiums of the so-called Cookie-Cutter Era (1961-1971),1 the Astrodome hosted both major-league baseball and National Football League teams. However, having earned the nickname “Eighth Wonder of the World” as the first domed stadium of its time, the Astrodome also attracted headliner events in many other sports. These include the UCLA-University of Houston college basketball “Game of the Century” (1968), the tennis “Battle of the Sexes” between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs (1973), a gymnastics exhibition by 1972 Olympic triple Gold Medalist Olga Korbut of the Soviet Union (1973), and championship fights involving legendary boxers Muhammad Ali (1966, 1967, two in 1971) and Sugar Ray Leonard (1981). According to Brock Bordelon’s article “Ode to the Astrodome,” that’s not all: “It … hosted polo matches, soccer and ice hockey games, bullfights, auto races, rodeos, conventions, [and] boat shows,” along with an Evel Knievel motorcycle jump.2

Like other circular-shaped, multipurpose stadiums of the so-called Cookie-Cutter Era (1961-1971),1 the Astrodome hosted both major-league baseball and National Football League teams. However, having earned the nickname “Eighth Wonder of the World” as the first domed stadium of its time, the Astrodome also attracted headliner events in many other sports. These include the UCLA-University of Houston college basketball “Game of the Century” (1968), the tennis “Battle of the Sexes” between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs (1973), a gymnastics exhibition by 1972 Olympic triple Gold Medalist Olga Korbut of the Soviet Union (1973), and championship fights involving legendary boxers Muhammad Ali (1966, 1967, two in 1971) and Sugar Ray Leonard (1981). According to Brock Bordelon’s article “Ode to the Astrodome,” that’s not all: “It … hosted polo matches, soccer and ice hockey games, bullfights, auto races, rodeos, conventions, [and] boat shows,” along with an Evel Knievel motorcycle jump.2

Following is a detailed review of the nonbaseball athletic history of the Astrodome, focusing on the more mainstream sports played under the roof.

Football

As a home for football, the Astrodome and other fixed-roof, multipurpose stadiums generally had two major advantages and two major disadvantages. The advantages were protection from harsh weather and, specifically for the home team, amplification of crowd noise. For players a disadvantage was the absence of natural sunlight. This required artificial turf, which could be punishingly hard in addition to presenting other injury hazards, such as players’ cleats getting caught and nasty rug burns. Of Astroturf, “The former trainer for the Houston Oilers claims the stuff was ‘a definite factor’ in the team’s losing four of its best players to knee injuries last season.”3 For fans the disadvantage involved sight lines and viewing angles. With most of the action in a baseball game taking place in a diamond-shaped area, and football being played on a rectangle, seat locations that were good for viewing one of the sports usually were not good for viewing the other. The Astrodome sought to mitigate this problem somewhat through the use of movable seating sections in the lower deck.4

Houston Oilers

The NFL’s Houston Oilers were a 29-year tenant of the Astrodome (1968-1996). The Oilers originally played in the 1960s American Football League, which eventually merged with the older NFL. Although the Astrodome was available for the Oilers in 1965, the team did not actually move in for another three years. Contract disputes delayed the Oilers’ debut at the Dome: “Originally scheduled to play at the brand new Harris County Domed Stadium, the Oilers at the last minute decide[d] to play at Rice Stadium,5 when they reject[ed] terms of the lease. Without the Oilers using the new stadium it would be renamed the Astrodome.”6

A November 20, 1978, contest at the Dome between the Miami Dolphins and Oilers was voted in a 2002 fan survey as one of the all-time greatest NFL Monday Night Football games. Bum Phillips, the Oilers’ coach in the latter half of the 1970s, recalled, “No one had ever taken the pro game to [the same enthusiasm of] the college level, where [all the fans] had pompoms and stuff like that.”7 In this game (and many others), Oilers running back Earl Campbell amazed observers by bowling over opposing players, his jersey often in tatters from defenders grabbing at him in unsuccessful attempts to tackle him. During the Oilers’ Astrodome years, their best playoff finishes were trips to the American Football Conference championship game (the qualifying game to get to the Super Bowl) after the 1978 and 1979 regular seasons. Both games were played in Pittsburgh, with the host Steelers winning each time.

Toward the end of the Oilers’ time in Houston, owner Bud Adams vigorously lobbied for improvements to the Astrodome’s football facilities and threatened to move the team to other cities. In September 1988 the Dome’s large animation scoreboard in the outfield was decommissioned and removed to increase football seating capacity by roughly 12,000 (from 50,594 to 62,439). According to the Astrodome’s application form for the National Register of Historic Places (2013), the removed scoreboard area “stretched 474 feet across the centerfield wall behind pavilion seats, and measured more than four stories high. Weighing 300 tons and requiring 1,200 miles of wiring, the sign encompassed more than half an acre.”8

The increased capacity did little to stabilize the Oilers’ status in Houston. A variety of developments led to fan discontentment to Adams’s decision to move the team to Nashville, Tennessee. On January 3, 1993, Houston blew a 35-3 lead in a playoff game at Buffalo, demoralizing much of the Oilers’ fan base.9 Further, as a sign of how poor the Dome’s football playing conditions had become, a 1995 preseason exhibition game between the Oilers and San Diego Chargers was canceled when the Astroturf field was ruled unfit for play.10

In 1993 Adams had begun campaigning for a new stadium to be built mostly with taxpayer dollars. Houston Mayor Bob Lanier refused to support the use of city tax funds for that purpose, nor did Adams find much support among the media, other sports owners, or other major players in the city.

As a result, Adams looked to Nashville, which along with the state of Tennessee was wooing him.11 His eventual deal with Nashville, reached in November 1995, involved construction of a new stadium at a total cost of nearly $300 million – none borne by Adams – and a 30-year commitment12 by the Oilers (later renamed the Tennessee Titans) to play in it. When it opened in 1999, the stadium seated 67,000 and included 120 luxury boxes. Adams also received a $28 million relocation fee and 100 percent of stadium revenue. (A few years after the Oilers left, Houston got a new football stadium built with extensive public funds.)

Other Professional Football Leagues

American sports have always featured upstart professional leagues attempting to compete (or at least coexist) with their more established counterparts. The American Football League was just one example. The 1970s and early 1980s were very active times for new leagues. Two had franchises in Houston: the World Football League (1974 and part of ’75) and the United States Football League (1983-1985). With the WFL, finances were so bad that franchises were locating to new cities literally on a week-to-week basis. The USFL also had financial difficulties. It won an antitrust lawsuit against the NFL in 1986, but the $1 damage award (tripled to $3 under antitrust law)13 obviously could not sustain the league.

The Astrodome hosted a team in each of these leagues. The Houston Texans of the WFL skipped town after only 11 games of the 20-game 1974 season, moving in midseason to become the Shreveport Steamer. The Houston Gamblers played during the USFL’s final two seasons. Despite the Gamblers’ brief existence, several big names were associated with the franchise. Quarterback Jim Kelly began his professional career with the team before going on to a Hall of Fame career with the Buffalo Bills of the NFL. Jack Pardee, a longtime NFL player and coach, was a head coach of the Gamblers; he later became a Houston coaching mainstay, leading the University of Houston from 1987 to 1989 and the Oilers from 1990 to 1994. Two assistant coaches for the Gamblers were Darrel “Mouse” Davis, known for the “Run and Shoot” offense, and John Jenkins, later a University of Houston head coach.

University of Houston

The University of Houston Cougars had a long run in the Astrodome (1965-1997), moving there from Rice Stadium. One highlight of the Cougars’ Dome tenure was a nationally televised Monday night game on September 12, 1977, in which the Cougars defeated UCLA, 17-13. From 1995 to 1997 the Cougars gradually increased the number of games played on-campus at Robertson Stadium, then moved there full time in 1998. The university’s new athletic director wanted its football games to have a campus atmosphere.14

In addition, Houston had not drawn well at the Dome. In 1989, despite a 9-2 record and an offense that averaged over 50 points per game – earning quarterback Andre Ware the Heisman Trophy – the Cougars’ average home attendance was only around 28,000. In their final year at the Astrodome, it was below 20,000.15

The phasing out of the University of Houston’s Astrodome tenure coincided with the demise of the Southwest Conference, of which the school was a member from 1976 to 1995. Well before officially disbanding, many of its schools, including the University of Houston, got in trouble with the NCAA, which may well have been a major factor in the Cougars’ failure to build more of a following.

After the Southwest Conference folded, Houston landed in Conference USA, so instead of getting to play annual games against prominent in-state rivals Texas and Texas A&M, the Cougars instead played a conference schedule against distant schools like Memphis. Cincinnati, and Tulane. These new opponents presumably carried relatively little interest to football fans in the Houston area.

A college football bowl game, the Astro-Bluebonnet Bowl was played in the Astrodome from 1968 to 1984, and in 1987.

Basketball

College basketball’s “Game of the Century,” a 71-69 win for the University of Houston Cougars over the UCLA Bruins, was played in the Astrodome on January 20, 1968. Houston and UCLA had played in the previous year’s Final Four (a 73-58 Bruins win) and Cougars coach Guy V. Lewis dreamed up the idea of a rematch in the Astrodome. The floor for the game was shipped from the Los Angeles Sports Arena and placed in the middle of the vast Astrodome floor. The list of superlatives associated with the game is extensive: a record basketball crowd at the time (52,693), first nighttime national telecast of a regular-season college basketball game, a battle of two legendary coaches (Lewis and UCLA’s John Wooden) and two legendary big men (UCLA’s Lew Alcindor, later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and the University of Houston’s Elvin Hayes), both teams undefeated coming in, and play-by-play of the national telecast being done by an up-and-coming broadcasting star, 33-year-old Dick Enberg.16

UCLA had a more successful experience in the Astrodome in 1971. The NCAA Final Four was held there, with the Bruins capturing the national championship. The 1971 Final Four presaged a later trend of the Final Four regularly being held in football/baseball-sized domed stadiums. The small size of a basketball court (94 x 50 feet), compared with a 100-yard-long football field, makes a game very difficult to view from the upper decks of a stadium. However, the novelty of basketball in a dome and the ability to sell more tickets than in a conventional arena kept domed stadiums viable as hoop hosts.

The Astrodome also played a limited hosting role for NBA basketball. In the Rockets’ first season in Houston (1971-72) after they moved from San Diego, the team played eight home games at the Astrodome (along with six at the adjoining Astrohall exhibition center, 21 at Hofheinz Pavilion on the University of Houston campus, and the remaining six games spread between El Paso, San Antonio, and Waco).17

The NBA held its annual All-Star Game at the Astrodome on February 12, 1989, with a crowd of 44,735 attending. On this day, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar came full circle, playing in his final All-Star Game near the end of his illustrious 20-year NBA career in the same building in which he had played for UCLA in the 1968 Game of the Century.

One additional piece of US pro basketball history, fascinating though obscure, is tied to the Astrodome. The American Basketball Association, which lasted from the 1967-68 season to 1975-76, was a rival to the NBA before folding and having four of its teams absorbed into the older league.18 On May 28, 1971, a so-called “Supergame” was held at the Astrodome, pitting all-star teams from the NBA and ABA against each other. Attendance was 16,364. According to blogger David Friedman:

The game used NBA rules in the first half (24-second shot clock, no three-point shot19) and ABA rules in the second half (30-second shot clock, three-point shot). Walt Frazier came off the bench to make seven of his eight field-goal attempts in the first half and the NBA led 66-64 after Elvin Hayes’ first half-buzzer beater. The game went back and forth until the NBA took a 108-98 lead in the fourth quarter. [Rick] Barry and Charlie Scott rallied the ABA to within a point with 47 seconds left, but Oscar Robertson drained two free throws to put the NBA up 123-120 with 32 seconds left. Frazier closed out the scoring with two more free throws at the 11-second mark. Frazier finished with a game- high 26 points and won a car as the game MVP.20

Tennis

Situated historically within the Women’s Rights Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, the September 20, 1973, Billie Jean King-Bobby Riggs tennis match at the Dome drew great international attention. A crowd of 30,472 attended; estimates of the television audience have ranged from 50 million viewers worldwide to 50 million in the United States and 90 million worldwide. The 55-year-old Riggs, who won the Wimbledon and US Open singles titles in 1939 and won again at the US Open in 1941, created a classic male-chauvinist persona (whatever his private attitudes actually were). If a male player as far removed from his prime as Riggs could defeat a top female player in her prime (King was 29), the implication would be that women’s tennis just wasn’t very good. Prior to playing King, Riggs had defeated another leading women’s player, Margaret Court, 6-2, 6-1, on May 13, 1973, in a much more low-key setting.

King later described the high stakes of the match: “I thought it would set us back 50 years if I didn’t win that match. … It would ruin the women’s tour and affect all women’s self esteem.”21 King and Riggs opted to play a three-out-of-five-sets match, presumably so that each could showcase his/her endurance. This decision is noteworthy because even today, more than 40 years after the King-Riggs match, major women’s championships still use a two-out-of-three format. King showed considerably greater fitness than Riggs, garnering a straight-sets victory, 6-4, 6-3, 6-3.

Soccer

Two soccer teams, the Houston Stars of the United Soccer Association (1967-1968) and Houston Hurricane of the NASL (1978-1980) called the Astrodome home during their brief runs. A recent history of soccer in Houston said the Stars led the league in attendance with an average attendance of over 19,000.22

“The Superstars”

A made-for-television sports franchise in the 1970s was ABC’s The Superstars. Superstar competitions pitted athletes from different sports against one another in several events, including swimming, running, tennis, and weightlifting. Athletes received points based on their performance in each event (10 for first place, 7 for second, etc.). Contestants could not compete in their own sport. Most of the Superstar programs featured competitions between men, but women also competed. There were also “Superteam” and “Celebrity Superteam” battles.

In 1975, the first year women competed, the Astrodome hosted the two semifinal competitions (covered by Sports Illustrated23). The final round was held at the main Superstars complex in Florida. Events contested in Houston included tennis, softball throwing, basketball shooting, swimming, rowing (held at Lake Conroe), bicycling, bowling, obstacle course, 60-yard dash, and one-fifth-mile run (because there wasn’t enough space in the Dome for a traditional quarter-mile oval).

Top finishers at the Astrodome included diver Micki King, speed skater Dianne Holum, and softball player Joan Joyce (first semifinal); and volleyball player Mary Jo Peppler, basketball player Karen Logan, and former Olympic sprinter Wyomia Tyus (second semifinal). Peppler went on to win the overall title in Florida. Billie Jean King took fifth in the second semifinal group and qualified for the finals, but she did not compete.24

Rodeo

The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, which was founded in 1931 and as of 2016 was held at NRG (formerly Reliant) Stadium, took place in the Astrodome from 1966 to 2002.25 Rodeo competitions are sanctioned by the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association. Contested events include bull riding, saddle bronc riding, calf roping, steer wrestling, and an all-around title.26 The annual event also features other festivities such as popular musical performers and a barbecue contest.

Conclusion

During its first decade (1965-1975), the Astrodome hosted an array of sporting events whose breadth and importance arguably have not been equaled by any other US sports venue within a 10-year period. The Astrodome was the only football-and-baseball-sized domed stadium during this decade. Novelty and uniqueness were probably the main reasons for the Astrodome attracting the events it did, rather than the quality of the viewing experience (especially from the upper decks).

Once the Superdome opened in 1975 for the NFL’s New Orleans Saints, it too began to attract major sporting events outside of its primary sport, including the basketball Final Four and prizefighting. At this point, the Astrodome’s uniqueness was lost.

The Astrodome’s precedent of hosting a major basketball game in a baseball/football-sized stadium has stood the test of time in some ways, but not others. The men’s basketball Final Four has consistently been held in domed stadiums rather than conventional arenas since the 1990s. However, every NBA team that once used a dome as a full-time home (e.g., the Detroit Pistons in the Pontiac Silverdome from 1978-1988) has abandoned the concept.

Some seemingly good news for the Astrodome’s legacy is that its application to the National Register of Historic Places was approved in 2014. Such a designation may be less important than it seems, however. National Register status does not prevent the demolition of a building.27 Further, there are 1.5 million structures in the Register, hardly making it an exclusive club.

One can find positive and negative aspects of the Astrodome’s nonbaseball activities. The college basketball Game of the Century and the King-Riggs tennis match were glamorous, exciting, and historic events that enhanced the Dome’s reputation. However, the physical facilities left much to be desired for athletes and spectators alike.

ALAN REIFMAN is professor of human development and family studies at Texas Tech University and is a SABR member. He is the author of the book “Hot Hand: The Statistics Behind Sports’ Greatest Streaks” (Potomac Books) and also contributed to the SABR-published book “Detroit Tigers 1984: What a Start! What a Finish!” Among his many sports blogs is one devoted to the history of the 1968 UCLA-Houston college-basketball “Game of the Century” played in the Astrodome (gameofthecentury.blogspot.com).

Notes

1 These stadiums include Atlanta-Fulton County (opened in 1965), Busch II (St. Louis, 1966), Oakland-Alameda County (1966), RFK (Washington, 1961), Riverfront/Cinergy (Cincinnati, 1970), Shea (New York, 1964), Three Rivers (Pittsburgh, 1970), and Veterans (Philadelphia, 1971). Years are from ballparks.com.

2 Brock Bordelon, “Ode to the Astrodome,” Astros Daily. astrosdaily.com/history/odetodome/.

3 Kenneth Denlinger, “Artificial Turf Brings Cheers – And Groans,” St. Petersburg Times, September 28, 1971.

4 Louis O. Bass, “Unusual Dome Awaits Baseball Season in Houston,” Civil Engineering: The Magazine of the American Society of Civil Engineers (January 1965). columbia.edu/cu/gsapp/BT/DOMES/HOUSTON/h-unusua.html.

5 The history of football in Houston during the Astrodome years cannot fully be understood without reference to Rice Stadium (on the Rice University campus), three miles away. Even though the annual enrollment at Rice, an academically elite institution, has typically been only a few thousand, the school erected a 70,000-seat stadium in 1950. Designed specifically for football, the stadium has a number of positive features, including a high percentage of seats between the goal lines. In fact, when Houston was awarded Super Bowl VIII (1974), it was held at Rice Stadium, rather than the city’s regular NFL home, the Astrodome. In the author’s view (developed while living in Houston from 1989 to 1991), Rice’s location in a residential neighborhood precluded greater use of the stadium for high-attendance (e.g., NFL) games, due to concerns over noise, traffic, and other disturbances. The university’s own team does not draw well. According to one recent estimate, Rice University’s home games draw between 13,000 and 20,000 fans (The Pecan Park Eagle, Rice Stadium Dreams, http://bill37mccurdy.com/2011/08/26/rice-stadium-dreams/).

6 Sports E-cyclopedia. Houston Oilers. sportsecyclopedia.com/nfl/tenhou/houoilers.html.

7 Mike Diegnan, “MNF’s Greatest Games: Miami-Houston 1978,” ESPN.com, December 4, 2002. espn.go.com/abcsports/mnf/s/greatestgames/miamihouston1978.html.

8 National Register of Historic Places, Registration form for Houston Astrodome (2013). nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001099.pdf.

9 One of the author’s friends who lived in Houston at the time told him that, after the loss to Buffalo, some of her neighbors went out into the street and publicly burned their Oilers’ paraphernalia!

10 Associated Press, “Astrodome Game Off Because of Rug,” Los Angeles Times, August 20, 1995. articles.latimes.com/1995-08-20/sports/sp-37194_1_exhibition-game.

11 Raymond J. Keating, “The NFL Oilers: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare: How Houston’s Struggle Against Stadium Subsidies Failed,” The Freeman, Foundation for Economic Education (April 1, 1998). fee.org/freeman/the-nfl-oilers-a-case-study-in-corporate-welfare/.

12 John Glennon, “Former Mayor Recalls Bud Adams’ Decision to Move Team to Nashville,” The Tennessean, October 21, 2013. archive.tennessean.com/article/DN/20131021/SPORTS01/310210071/Former-mayor-recalls-Bud-Adams-decision-move-team-Nashville.

13 Paul Domowitch, “USFL Dealt Crippling Blow[;] Jury Awards $3 In Antitrust Suit,” Philadelphia Daily News. July 30, 1986. articles.philly.com/1986-07-30/sports/26099171_1_usfl-attorney-harvey-myerson-damage-award-nfl-attorney.

14 James Beltran, “Next Season’s Home Games to Be Played at Robertson,” Daily Cougar. archive.thedailycougar.com/vol63/86/News1/862698/862698.html.

15 University of Houston 2015 Football Media Guide. grfx.cstv.com/photos/schools/hou/sports/m-footbl/auto_pdf/2015-16/misc_non_event/15mediaguide.pdf.

16 Eddie Einhorn (with Ron Rapoport), How March Became Madness: How the NCAA Tournament Became the Greatest Sporting Event in America (Chicago: Triumph, 2006). Einhorn produced the television broadcast of the UCLA-Houston “Game of the Century,” and his book provides extensive interviews with many of the principals from the game. The book also comes with a DVD of the second half of the UCLA-Houston basketball game (the only footage that exists of the original broadcast).

17 Houston Rockets 2008-09 Media Guide. nba.com/media/rockets/MediaGuide0809_page173.212.pdf.

18 These teams were the Denver Nuggets, Indiana Pacers, San Antonio Spurs, and the then-New York Nets.

19 The NBA adopted the three-point shot in 1979-80.

20 David Friedman, “Supergames I & II: The 1971 and 1972 NBA-ABA All-Star Games,” 20-Second Time-Out Blog (February 23, 2009). 20secondtimeout.blogspot.com/2009/02/abas-unsung-heroes.html. One more Supergame was played the next year at Nassau Coliseum on Long Island, New York.

21 Larry Schwartz, “Billie Jean Won for All Women.” espn.go.com/sportscentury/features/00016060.html.

22 “A Soccer History of Houston.” U.S. National Soccer Players. ussoccerplayers.com/a-soccer-history-of-houst.

23 Curry Kirkpatrick, “There Is Nothing Like a Dame,” Sports Illustrated, January 6, 1975. si.com/vault/1975/01/06/616978/there-is-nothing-like-a-dame.

24 An excellent historical website on the competition exists, known as “The Superstars.org.” Within the larger website, pages detailing the Astrodome event are thesuperstars.org/comp/75wpr1.html and thesuperstars.org/comp/75wpr2.html.

25 “Looking Back at the History of the Rodeo,” Houston Chronicle, February 13, 2015. chron.com/entertainment/rodeo/article/Looking-back-at-the-history-of-the-rodeo-6070965.php.

26 “Several World Titlists Win Big Bucks at Houston Rodeo,” Livestock Weekly, March 19, 1998. livestockweekly.com/papers/98/03/19/whlprca.asp.

27 Associated Press, “Astrodome Named Historic Place,” ESPN.com, January 31, 2014. espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/10385397/houston-astrodome-added-national-register-historic-places.