Babe Ruth’s Blasts at Braves Field

This article was written by Bob Brady

This article was published in Braves Field essays (2015)

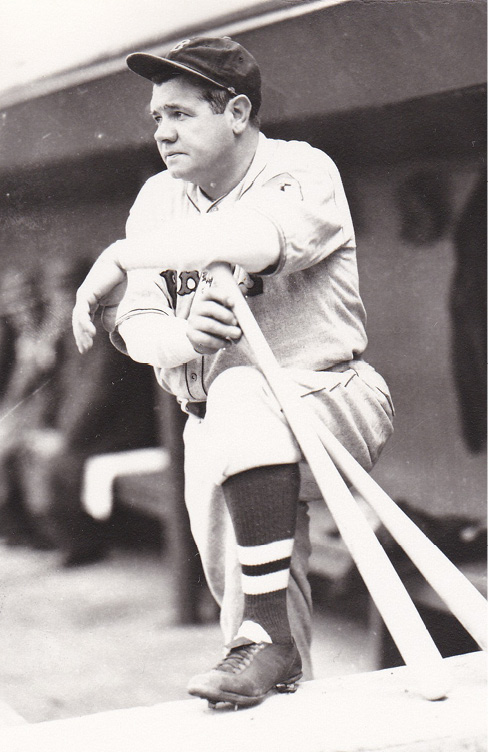

The Bambino awaits his at-bat at Braves Field. (Courtesy of Boston Braves Historical Association archives)

Some might be surprised to learn that Babe Ruth hit memorable regular-season home runs at the “Home of the Braves” while wearing the uniform of the New York Yankees as well as in his Boston Braves togs. Popularly referred to as the “Wigwam” during most of its existence, Braves Field was not unfamiliar territory to the legendary Bambino. In his first World Series start, Ruth had hurled a masterful complete-game 14-inning, 2-1 victory for the Red Sox over the Brooklyn Robins in Game Two of the 1916 fall classic at the Hub’s National League diamond. During Babe’s Yankees years, the Red Sox would borrow Braves Field to play Sunday home games when its principal tenant was on the road. Restrictive so-called Blue Laws prevented the Red Sox from using Fenway Park on the Sabbath due to its close proximity to a house of worship.

Even on a Sunday afternoon with the “home team” Red Sox destined for a last-place finish, a visit by the Yankees was guaranteed to draw a crowd. Some 25,000 fans filed into Braves Field on June 30, 1929, as Miller Huggins’ reigning World Series champions took to the unfamiliar senior-circuit turf. Boston valiantly battled the powerful New Yorkers but could not overcome the heroics of George Herman Ruth, who drove in four of the Yankees’ six runs in the visitors’ 6-4 triumph. In the top of the fifth inning, facing Deacon Danny MacFayden, the Babe blasted a baseball approximately 470 feet into the top row of the center-field bleachers. It was his 16th circuit clout of the campaign. These bleacher seats had not been part of the ballpark’s original design but had been hastily installed in 1928 to reduce Braves Field’s huge outfield dimensions that reflected its pre-Ruthian Deadball Era design. This seating lasted only a few seasons before being permanently dismantled. The innovation had failed to produce benefits to the home occupant that outweighed advantages gained by their opponents.

A near replay of that June day’s events took place as the 1929 season drew to a close. The Yankees came to town for a one-day visit on Sunday, September 1. The Wigwam’s turnstiles rapidly spun some 28,000 ticket holders into the friendly confines. Again the Red Sox went down to defeat by a 6-4 score. In the first inning, the Sultan of Swat stepped up to the plate and drove southpaw Billy Bayne’s second pitch like a rocket to center field, where it eventually banged into a billboard that sat atop the bleacher stands. Ruth’s 40th circuit clout carried as far as his June shot before it was stopped by the interfering barrier.

The Bambino’s mightiest Braves Field blast took place the succeeding season. On May 18, 1930, New York routed the Red Sox, 11-0, as 25,000 folks looked on. In a first inning at-bat, Ruth sent a pitch by Big Ed Morris into the ballpark’s famed “Jury Box,” where it finally landed about two rows in front of the elevated back scoreboard. A contemporary newspaper account called the clout “one of Babe’s heartiest hits in his whole career.”1 The reporter further commented that the homer was “the longest drive ever hit to right field in Braves Field since they first fenced in the land on the banks of the Charles, fifteen years ago.” Some speculated that Ruth had exerted such force on the spheroid that it would have reached the Commonwealth Armory (the current site of the Agganis Arena) across Gaffney Street (now Agganis Way), 490 feet from home, had it not been impeded by clipping the top scoreboard portion of the Wigwam’s tiny right-field section and rebounding into the stands.

The Wigwam was the site of a rare nonbatting Ruthian event on the ending day of the 1930 season. New York sat in third place in the junior circuit while Boston owned its basement. On Sunday, September 28, the Babe was handed the ball and took to the Braves Field mound for the first time there since his 1916 World Series triumph. He hadn’t pitched in a major-league contest since 1921. Showing a little rust, Ruth allowed 11 hits and three runs in hurling a complete-game 9-3 victory. Teammate Lou Gehrig also took the opportunity to play out of his traditional position at first base for the only time that year and patrolled the Wigwam’s left field. Ruth “cursed” his former team with its 102nd defeat of the campaign.

Ruth’s final majestic blow at Braves Field occurred during his National League debut, on April 16, 1935. The 40-year-old slugger had been unceremoniously waived by the Yankees and was lured back to Boston by financially strapped Braves owner, Judge Emil Fuchs. Opening Day was designated “Judge Fuchs Day,” in part for this apparent early attempt to “reverse the curse.” Despite the frigid weather, 20,000 fans came to watch the historic event and were not disappointed. With all eyes upon him, the Bambino responded in the fifth inning the way he had done 723 times before in regular and postseason play. Facing future Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell, Ruth bludgeoned an offering 430 feet into the narrow runway between the right-field pavilion and the Jury Box, driving in what proved to be the game-winning run. Part of that runway and a portion of the pavilion exist today within the confines of Boston University’s Nickerson Field. You still can actually stand near the landing area of Ruth’s last home run in Boston!

Ruth also provided the contest’s fielding gem. Although he was originally penciled in to play first base, a pregame strategic change found him in left field. There, in the fifth, Ruth had to madly dash in, plunging headlong to spear a shot off of Hubbell’s bat and prevent a Giants comeback. During the sixth inning, snowflakes began to drift down on the field, causing an attending band to strike up “In the Good Old Summer Time” followed by “Jingle Bells.” Unfortunately for the Babe, the inaugural game was not an accurate predictor of what was to come. An aged and aching Ruth would soon unhappily retire, believing that he had been deceived regarding the club’s alleged promise of front office/managerial duties. The “Ruth-less” Braves would win only 37 more times during the 1935 season (losing 115) and a deluge of “red ink” would force Judge Fuchs to abandon his ownership position.

Two other Boston Braves and Braves Field tidbits relating to the mighty Babe are also worthy of mention. Ruth made his last appearance as an active player at Fenway Park during the April 14, 1935, City Series preseason exhibition game between the Red Sox and Braves. Performing for the “visiting” Tribe, first baseman Ruth failed to get a hit in three at-bats during the Braves’ 3-2 triumph over their in-town rivals in a contest that also marked the Boston debut of new Red Sox player-manager Joe Cronin.

Babe Ruth’s final regular-season visits came as a member of Brooklyn Dodgers manager Burleigh Grimes’ “brain trust.” During the 1938 season, Ruth served as a coach for Brooklyn, but as in his Braves days, was employed more for his appeal as a gate attraction. In Boston the Bambino assumed his post in the first-base coaching box opposite the visitors dugout at a ballpark that was now nicknamed the Beehive. When Boston’s senior circuit entry renamed itself the Bees in 1936, Braves Field was rebaptized as National League Baseball Field. The Bambino’s official appearances for four different big-league teams (Red Sox, Yankees, Braves, and Dodgers) is unique to this former National League ballpark, adding further luster to the site’s importance as a part of baseball history.

BOB BRADY joined SABR in 1991 and is the current president of the Boston Braves Historical Association. As the editor of the Association’s quarterly newsletter since 1992, he’s had the privilege of memorializing the passings of the “Greatest Generation” members of the Braves Family. He owns a small piece of the Norwich, Connecticut-based Connecticut Tigers of the New York-Penn League, a Class-A short-season affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. Bob has contributed biographies and supporting pieces to a number of SABR publications as well as occasionally lending a hand in the editing process.

Notes

1 New York Times, May 19, 1930.