Ball Four at 50 and the Legacy of Jim Bouton

This article was written by Robert Elias - Peter Dreier

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

Amidst the current upsurge of social activism among professional athletes, it is worth recalling the enormous contribution of Jim Bouton, one of the most politically outspoken sports figures in American history. Among professional team sports, baseball may be the most conservative and tradition-bound, but throughout its history, rebels and mavericks have emerged to challenge the status quo in baseball and the wider society, none more so than Bouton. During his playing days, Bouton spoke out against the Vietnam War, South African apartheid, the exploitation of players by greedy owners, and the casual racism of the teams and his fellow players.1 When his baseball career ended, he continued to use his celebrity as a platform against social injustice.

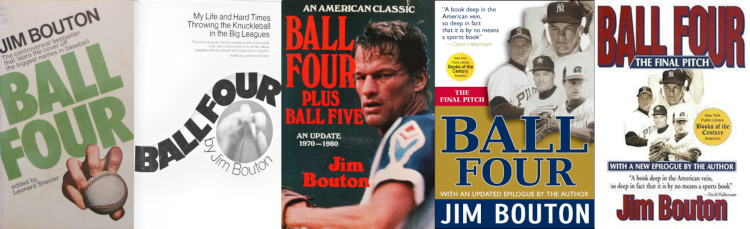

Bouton’s baseball memoir, Ball Four—published in 1970—may be the most influential sports book ever written.2 It was the only sports book to make the New York Public Library’s 1996 list of Books of the Century.3 Time magazine lists Ball Four as one of the 100 greatest non-fiction books of all time.4 But the baseball establishment ignored the 50th anniversary of this revolutionary book. Even after the COVID-19-shortened 2020 season, neither the Hall of Fame nor Major League Baseball planned any celebration.

Bouton—who died in 2019 at age 80—wrote Ball Four after his best days as a hard-throwing All-Star pitcher with the New York Yankees were over and he was trying to make a comeback as a knuckleball pitcher. He wanted athletes to speak out for themselves, to refuse to conform, and to defy complacency. Following his own advice, he was an early supporter of anti-Vietnam War presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and he served as a Democratic Party convention delegate for anti-war presidential candidate George McGovern in 1972.5

In Ball Four, Bouton accused organized baseball of hypocrisy: portraying a squeaky clean image while ignoring burning social issues. Bouton condemned baseball’s support for the Vietnam War. He attacked icons such as the Reverend Billy Graham, disputing his claim that communists had organized anti-war protests. While Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn said he couldn’t remember any players being ostracized for anti-war statements, Bouton recounted being repeatedly heckled for his anti-war views by players and fans: “They wanted to know if I was working for Ho Chi Minh.”6

Ball Four—funny, honest, and well-written—revealed aspects of major league baseball that sportswriters and previous ballplayer memoirs had ignored. Bouton expressed his outrage at owners who exploited players and at players who showed disrespect for the game he loved. He didn’t hold back naming names or describing the lives and antics of ballplayers both on and off the field. It portrayed laudable characters and accomplishments, but also aspects of players’ heavy drinking, crass language and behavior, pep pills and drug use, conservative political views, questionable baseball smarts, anti-intellectualism, womanizing, voyeurism, and extramarital affairs. It described boys being boys: human, fun-loving, vulnerable, and sometimes immature. That is, ballplayers were normal young men, with some special skills, but otherwise not necessarily idealistic heroes, as they had been portrayed by most sports reporters. Exposing what had always been under wraps generated a firestorm of protest from players, management, and sportswriters.7

Ball Four is ostensibly a diary of Bouton’s 1969 season as a pitcher with the lowly Seattle Pilots and Houston Astros, but the most memorable and controversial parts of the book deal with his years with the Yankees. Decades before baseball was rocked by scandal over PEDs, Bouton disclosed players’ widespread use of amphetamines (aka “greenies.”). One of the most controversial parts of the book was his revelation that his Yankees teammate Mickey Mantle, whom sportswriters viewed as baseball’s golden boy, was an alcoholic who often blasted towering home runs while nursing a hangover. As Bouton told Fresh Air host Terry Gross during a 1986 radio interview, his portrayal of Mantle “wasn’t really even so much as a put-down of Mickey Mantle as it was a story of what a great athlete he was.”8

Since the book’s original publication in 1970, Ball Four has been updated, expanded, reprinted, and republished numerous times.

Bouton acknowledged with candor that he was a participant, not just an onlooker, in these activities. And he described his clashes with his coaches and team executives, over salary disputes and his desire to use his knuckleball as his main pitch, as well as his outspoken views about politics. “Baseball, football— they’ve always felt the need to be patriotic,” Bouton observed, “to be on the side of America and might, supporting wars no matter what, and so going against that conservative bent, to have a break in their ranks: This was a little too much for them.”9

In the past half-century since Ball Four’s publication, many athletes and writers have sought to outdo each other with “tell-all” books highlighting tales of drugs and sex among pro athletes, but they lack Bouton’s skills as a sociological observer and political renegade.10 Bouton was not above recounting juvenile hijinks among himself and fellow players, but he reserved most of his outrage for major league baseball’s, and America’s, corporate and political establishment.

Even before he gained notoriety for Ball Four, Bouton was not the typical ballplayer. In his free time, he painted watercolors and made costume jewelry. He and his first wife adopted a Korean mixed-race child at a time when few couples did so. Bouton not only complained about his own salary, he was also a “clubhouse lawyer” and stood up for fellow players if management cheated them. In the book, Bouton claimed that he “wanted to nail those guys [management] because they stole money from the players.”11 By illuminating his own salary battles with the Yankees and their dirty tricks in dealing with him and other players, Bouton revealed baseball’s unfair labor conditions.

As a white professional athlete in the late ‘50s and 1960s, he was unusually curious about the world around him and the burgeoning movements for social change. In the book, Bouton described a visit he and fellow ballplayer Gary Bell made to the University of California campus in Berkeley. They:

…walked around and listened to speeches— Arab kids arguing about the Arab-Israeli war, Black Panthers talking about Huey Newton, and the usual little old ladies in tennis shoes talking about God. Compared with the way everybody was dressed Gary and I must have looked like a couple of narcs. So some of these people look odd, but…anybody who goes through life thinking only of himself with the kinds of things that are going on in this country…well, he’s the odd one. Gary and I are really the crazy ones…We’re concerned about getting the Oakland Athletics out…about making money in real estate, and about ourselves and our families. These kids, though, are genuinely concerned about…Vietnam, poor people, black people…and they’re trying to change them. What are Gary and I doing besides watching?…I wanted to tell everybody, Look, I’m with you, baby. I understand. Underneath my haircut I really understand that you’re doing the right thing.’12

By today’s standards, the book is quite tame. But at the time, it was shocking. As Mitchell Nathanson explains in his biography, Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original,13 Bouton’s fellow ball players were outraged that he had broken the code by revealing stories from the locker rooms and hotel rooms. Many fans were upset by Bouton’s revelations about the private lives of their favorite players. Bouton was excoriated by baseball officials, including Commissioner Kuhn, who called it “detrimental to baseball” and tried to force Bouton to sign a statement saying that the book was a total fiction. Bouton was attacked by sportswriters, who viewed their job as protecting the integrity of the game and the private lives of the players whom they relied on for interviews and stories.

Through extensive interviews with Bouton, as well as his family, friends, ballplayers, political activists, and others, Nathanson shows why and how Bouton was unique among the thousands of pro athletes who came before him. Today, we are less shocked when athletes speak out about social and political issues. The Trump era triggered an upsurge of activism and outrage among pro athletes, led by players like NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, MLB relief pitcher Sean Doolittle, NBA star LeBron James, soccer great Megan Rapinoe, tennis star Naomi Osaka, and many others. Some have been successful at raising consciousness and engendering debate while being shut out of their sports or dropped from teams—like Kaepernick and the NFL’s Chris Kluwe—while others have maintained their status as stars. James raised millions of dollars to ensure voting rights leading up to the November 2020 election. Players on championship NFL, NBA, and MLB teams, as well as the World Cup-winning women’s soccer team, refused invitations to celebrate their victories with Trump at the White House. Pro athletes responded to the murder of George Floyd and the police shooting in Kenosha, Wisconsin, of Jacob Blake. NBA, WNBA, and MLB teams refused to play scheduled games to protest the Blake shooting.

In his time, Bouton was not alone in his views, but the many other celebrated athletes who shared his beliefs kept them to themselves. The handful of exceptions included basketball stars Bill Russell and Elgin Baylor, boxer Muhammed Ali, tennis great Arthur Ashe, baseball star Roberto Clemente, and Olympic track stars John Carlos and Tommie Smith. But Bouton was rare in two respects. He was white and, except for a few spectacular years with the Yankees, he was not a major star.

Ball Four revolutionized sports writing, forever changing how journalists cover sports and how fans think about their favorite teams and players. The book’s critics focused on how it assaulted the sanctity of the locker room. But for MLB owners, Bouton’s real threat was challenging their economic power and, more broadly, America’s unequal economic system and the undue influence of big corporations. Bouton loved baseball, but not the baseball establishment which, he believed, took advantage of powerless, unorganized, and under-educated athletes. In a clubhouse discussion one day when Bouton was still with the Yankees, his teammates claimed a fair minimum salary should range between $7,000 and $12,000. Bouton was scolded when he proposed $25,000, but he pointed out that: “…everyone in this room has a PhD in hitting or pitching. We’re in the top 600 in the world at what we do. In an industry that makes millions of dollars, and we have to sign whatever contract they give us? That’s insane.”14

Playing before the ascendancy of the Major League Baseball Players Association, Bouton revealed that major leaguers led lives with little financial or professional security. The owners cared about nothing except their profits. They kept salaries indecently low, and traded or demoted even the most loyal players. At the time, under major league contract terms, ballplayers were little more than indentured servants, with no ability to negotiate with their team owners for better salaries, benefits, or working conditions. Salary negotiations were a farce, and most players couldn’t make a living on their baseball pay, despite generating millions in profits for owners.15 Except for the superstars, ballplayers led a vagabond, insecure existence. By disclosing these conditions, Bouton thought fellow ballplayers would appreciate him blowing the whistle. Instead, they complained about him violating their privacy and tarnishing their reputations.

By the late 1960s, however, the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) was beginning its assault on their peonage. In 1968, two years after Marvin Miller joined the union as executive director, the MLBPA negotiated the first-ever collective-bargaining agreement in professional sports. Minimum salaries increased from $6,000 to $10,000. Two years later, the MLBPA established players’ rights to binding arbitration over salaries and grievances. Most importantly, Bouton helped overturn the renewal clause that prevented players from offering their services to the highest bidder. In 1970, with union support, outfielder Curt Flood filed a lawsuit against Major League Baseball for trading him without his consent, which he claimed violated federal antitrust laws. “Marvin Miller called me up,” Bouton recalled, “and said, ‘We’d like to have you put Ball Four in testimony against the owners.’” The union had been accumulating “stories about ballplayers being taken advantage of by the owners.” Miller claimed that Ball Four “played a significant role in the removal of baseball’s reserve clause.”16

In 1972, the US Supreme Court ruled against Flood, but in 1975, Miller persuaded pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally to play that season without a contract, and then file a grievance arbitration. The arbitrator ruled in their favor, paving the way to free agency, which allows players to choose which team they want to work for, veto proposed trades, and bargain for the best contract. By then Bouton was out of the majors, but it was part of his legacy. While Bouton’s book became a bestseller, he paid dearly in baseball, temporarily blacklisted from playing and excluded from ballparks such as Yankee Stadium.17

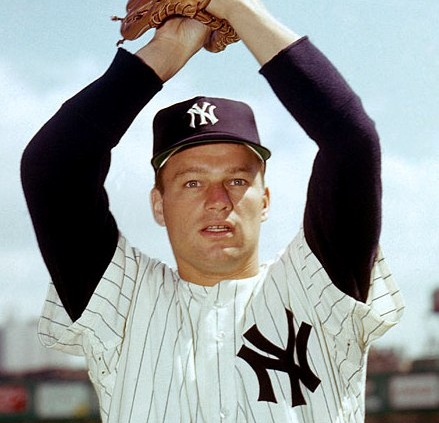

Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1939, Bouton attracted attention as a pitcher after moving to the Chicago suburbs in his teens. He studied painting briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago, attended Western Michigan University for a year, and signed a contract with the New York Yankees in 1958. After three years in the minor leagues, he made the Yankees roster in 1962. In 36 appearances, including 16 starts, he went 7–7 with a 3.99 ERA, and got a World Series ring when the Yankees beat the San Francisco Giants in the Fall Classic.

Bouton’s agitations for fair treatment by management began years before the idea of writing a book began to flicker. After earning the MLB minimum ($7,000 according to Ball Four, though other sources list the minimum at $5,000) as a rookie, Bouton asked for a raise. He was offered a tiny bump, if he “made the team.” Bouton was incredulous: “What do you mean if I make the team?” he asked Yankees executive Dan Topping. “I was with the team the whole year; why wouldn’t I make it? Why would you even want to plant that kind of doubt in the mind of a rookie pitcher?”18

Resorting to the usual ploy, Topping reminded Bouton that he’d be making more money in October since the Yankees always made the World Series. Bouton said: “Fine, I’ll sign a contract that guarantees me $10,000 more at the end of the season if we don’t win the pennant.” Instead, Topping offered the same contract, regardless whether Bouton made the team, and Bouton again refused. Yankees General Manager Roy Hamey called Bouton, yelling that he’d be making the biggest mistake of his life if he didn’t sign. Bouton hung up on him. Topping tried again, and they settled for a bigger but still meager raise.19

In 1963, a six-month hitch in the Army kept Bouton out of the rotation until mid-May, but he nevertheless had a sensational season, going 21–7 with a 2.53 ERA plus 10 relief appearances. He emerged as one of baseball’s top young pitchers and appeared in that season’s All-Star Game. The Los Angeles Dodgers beat the Yankees in the World Series by winning four straight games. Bouton pitched superbly in game three, giving up only four hits and one run in seven innings, but he was bested by Dodger hurler Don Drysdale, who threw a three-hit shutout.

After that season, Bouton claimed he deserved a much bigger raise, but again the Yankees stonewalled. Bouton asked the Yankees to double his salary to $21,000. GM Ralph Houk refused, offering $18,500 instead. Bouton told The New York Times, “Right now I wouldn’t even say we were in the same neighborhood.” Houk threatened to reduce his salary by $100 each day he held out and report to spring training camp. With few alternatives, Bouton signed for $18,500.20 He might not have even gotten that had he not broken the taboo against discussing one’s salary with teammates and the press. He told the angry Houk that he talked to reporters to “let them know I’m being reasonable” in his salary requests. Many writers began to take his side.

Bouton repeated his pitching success in 1964, finishing 18–13 with a 3.02 ERA. He led the league in starts and won two World Series games. But besides his salary demands, Bouton began speaking out on social issues, and his teammates and Yankees management began regarding him as a flake. They found him too intelligent and outspoken for his own good, an outside agitator disturbing the status quo. He typically sat at the back of the team bus, reading! He was considered a free thinker, “which in those days was one step away from being a Communist, to conservative sports minds,” observed sportswriter Ron Kaplan.21

The Yankees tolerated this until Bouton suddenly became a marginal performer in 1965. Probably from overuse the previous two years, Bouton began having arm problems and slipped to 4–15 with a 4.82 ERA as the Yankees dropped to sixth place. His ERA bounced back in 1966 to 2.69, but poor run support held his won-loss record to 3–8.

Bouton and his liberal opinions had become expendable. After opening the 1967 season with the Yankees, the club demoted him to their Syracuse farm team, where he posted a 3.36 ERA but only a 2–8 record.22 He made it back to the majors in August, pitching much better, and made the Yankees roster again the next year.

His tenure with the Yankees was already in jeopardy when the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SAROC) approached him in early 1968 to sign a petition protesting the ban on non-white athletes on that country’s team, scheduled to play in the Olympic Games in Mexico City. In a country that was 80% black, the team was 100% white. Bouton became friendly with SANROC’s executive secretary—South African anti-apartheid activist Dennis Brutus—who Bouton called “the greatest man I ever met.”23

“We need fellow athletes to stand up for us and change this injustice,” Bouton argued. Signing the petition, he thought, was a “no brainer.”24 Bouton believed his would be one of hundreds of signatures from major leaguers, but only a few, including his teammate Ruben Amaro, signed. The poor response appalled Bouton. A planned press conference was canceled, but the two ballplayers traveled to Mexico City anyway, only to be rebuffed by the Olympic Committee. “They knew all about the discrimination against the black South African athletes,” Bouton observed, “and they simply didn’t care. They were a bunch of pompous racists. It was sickening.”25 He wrote about the issue and his ordeal for Sport magazine later that year.26

After his 1962 rookie year, and years before he ever considered writing a book, Bouton made waves by asking for better contract terms from the New York Yankees. The Yankees did not accede. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The Yankees sold Bouton mid-season to the expansion Seattle Pilots, a team that wouldn’t begin play until 1969. Bouton finished out the 1968 season with the Triple-A Seattle Angels, teaching himself how to throw a knuckleball because he had lost the velocity on his fast ball.

During his time with the Yankees, Bouton had taken notes. Bouton had befriended sportswriter Leonard Shecter, who encouraged him to keep it up while playing for the Pilots (and later, the Astros).27When the Pilots played in New York, Bouton would visit Shecter’s apartment and the two men would look over Bouton’s notes, which he wrote on envelopes, toilet paper, hotel stationery, and airplane airsick bags. (Bouton’s notes are now housed at the Library of Congress). These notes and sessions ultimately produced Ball Four.

Shecter was Bouton’s collaborator and co-author, not his ghost-writer. Bouton was busy trying to make his baseball comeback, but, as Nathanson notes, he was already glimpsing the possibility of a second career as a writer and journalist. Overall, Bouton pitched in 80 games that season, almost all in relief. He had reason to believe he’d resurrected his career.

In 1969, Bouton supported students protesting the war and signed anti-war petitions. He spoke against the Vietnam War at a rally in New York’s Central Park. Eager to participate and recruit other athletes, Bouton observed: “What I’m doing now, with the Moratorium group, is no major concerted effort. I’m just feeling some players out. But it is not like Jim Bouton is trying to rouse guys. A lot of them feel the same way I do, about the war and about other types of involvement. And there are many who want to express these feelings.” He added, “We’re always being used for telling kids to stay in school, to brush their teeth. Why can’t we tell them how we feel about things like the Vietnam War? And athletes do have influence.”28

Bouton was also bothered by his teammates’ racism and the institutional racism of the teams and the leagues. He was repulsed by the segregation in spring training (mostly held in Florida) and during the season in Southern cities. He was angered watching Emmett Ashford—who in 1966 became the first black major league umpire—being repeatedly ridiculed by his white colleagues. More than a decade after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line in 1947, Bouton witnessed his teammates subject Elston Howard, the Yankees’ first black player, to endless humiliations.29

A handful of baseball players did use their celebrity to express their political views. For example, following Martin Luther King’s assassination in April 1968, Pittsburgh Pirates stars Roberto Clemente and Maury Wills urged their teammates to refuse to play on Opening Day and the following day, when America would be watching or listening to King’s funeral. At a team meeting, the players unanimously endorsed the idea and persuaded the Houston Astros players, whom they were scheduled to play, to join them. Players on other teams followed their lead. Commissioner William Eckert, his back against the wall, reluctantly moved all Opening Day games to April 10. But such rebellions were rare, especially among white players.

Bouton was part of Houston’s starting rotation through May, making his last start on May 24. Ball Four came out in June 1970. Bouton struggled to regain his place in the rotation, but the backlash against the book didn’t help.

A few ballplayers defended Bouton’s book. Cy Young Award winner Mike Marshall said, “I thought it was a celebration. I thought it was funny, and made us look far better than we were. It made us look human, and vulnerable, and struggling, all the things we were.”

But most players didn’t see it that way. They viewed Bouton as a “rat,” revealing their foibles, weaknesses, and indiscretions. Bouton wasn’t the very first to write a candid diary, but he may as well have been. He was following in the footsteps of another pitcher-turned-writer, Jim Brosnan, who published The Long Season in 1960.30 Chronicling his experience of splitting the 1959 season between the St. Louis Cardinals and the Cincinnati Reds, Brosnan avoided the usual, sanitized portrayal, addressing some issues normally confined to the clubhouse. Although former major leaguer and sports broadcaster Joe Garagiola called the strait-laced Brosnan a “kooky beatnik,”31 The Long Season offered relatively tame revelations. While Brosnan broke ground and began lifting the veil, Bouton’s book was more irreverent and forthright, and engendered a stronger backlash.

When Bouton faced the Cincinnati Reds, Pete Rose shouted: “Fuck you, Shakespeare.”32 In three successive anti-Bouton articles, New York Daily News sportswriter Dick Young portrayed Bouton as a “social leper” and a “commie in baseball stirrups.”33 To him, Bouton had committed the cardinal sin: he tarnished baseball icon Mickey Mantle, by suggesting that maybe it wasn’t Mantle’s injuries that shortened his career but rather his drinking problem and skirt-chasing until all hours of the morning.34

The Houston Astros management forbade their radio and TV announcers from mentioning the book.35 American League president Joe Cronin called Ball Four “unforgivable.”

Commissioner Kuhn demanded a meeting with Bouton. Before that meeting, however, Bouton got a boost from a positive book review by New York Times sportswriter Robert Lipsyte: “Bouton should be given baseball’s most valuable salesman of the year award. His anecdotes and insights are enlightening, hilarious, and most important, unavailable elsewhere. They breathe new life into a game choked by pontificating statisticians, image-conscious officials, and scared ballplayers.”37

Not all fans turned against Bouton. On the day of the meeting with Kuhn, two college freshmen, Steve Bergen and Richard Feuer, appeared outside Kuhn’s office, protesting with placards reading: “Jim Bouton is a Real Hero,” “No Punishment for Exposing the Truth,” and “Kuhn: Stop Repression and Harassment.”38

Like other young antiwar activists and students of the time, they viewed Kuhn as an example of the establishment trying to shut up their generation. According to Bergen: “…[Dick] Young’s comments smacked of the same authoritarian putdown of kids growing up in the ‘60s. Bouton was a hero for being willing to tell the truth about an aspect of society… the whole ‘60s movement was about questioning authority.”39

Players union executive director Marvin Miller, union attorney Richard Moss, and Shecter joined Bouton at the meeting with Kuhn. The commissioner claimed that Bouton was undermining baseball, but Bouton responded: “You’re wrong… People will be more interested in baseball, not less… People are turned off by the phony goody-goody image.” Kuhn said Bouton owed “it to the game because it gave you what you have,” but Bouton protested: “I always gave baseball everything I had. Besides, baseball didn’t give me anything. I earned it.”40

Kuhn ordered Bouton to release a statement saying he falsified or exaggerated his stories, but Bouton refused. When Kuhn told him to regard the meeting as a warning, Miller shot back: “A warning against what…against writing about baseball?… You can’t subject someone to future penalties on such vague criteria.”41 Kuhn told Bouton that he was going to issue a statement threatening players with punishment for any further writing like Ball Four. He told Bouton that he should remain silent. Again, Bouton refused. The controversy helped turn the book into a bestseller.42

New York Congressman Richard Ottinger claimed the Commissioner’s actions were “part of a growing mood of repression in the country” that indicated “an intolerable arrogance [by] the official baseball establishment.” Ottinger threatened to approach the House Judiciary Committee about Kuhn’s denial of individual rights.43

Meanwhile, Bouton’s pitching was not improving. After being demoted to the Oklahoma City minor league team, he had two more bad starts in Triple A and decided to retire from playing, but the far-reaching effects of Ball Four were just beginning.

Bouton’s book helped change sports writing. While the old-timers condemned Bouton, younger people who read Ball Four became sportswriters because of the book. A new wave of writers abandoned the deification of ballplayers and instead looked for unconventional angles. In The New Yorker, Roger Angell described the book as “a rare view of a highly complex public profession seen from the innermost inside, along with an even more rewarding inside view of an ironic and courageous mind.”

According to Stephen Jay Gould, a Harvard paleontologist and baseball writer, Ball Four inaugurated a “post-modern Boutonian revolution,” revealing that “heroes were not always what they were thought to be, questioning the masculine ideal in the professional game, and encouraging the reader to look beyond the media’s interpretations.” George Foster of the Boston Globe called the book a “revolutionary manifesto.” New York Times writer David Halberstam observed that Bouton “has written… a book deep in the American vein, so deep in fact that it is by no means a sports book….. [A] comparable insider’s book about, say, the Congress of the United States, the Ford Motor Company, or the Joint Chiefs of Staff would be equally welcome.”

As MLB historian John Thorn later observed, Ball Four was “a political work, and a milestone in the generational divide that characterized the 1960s. It is the product of a widespread rebellion against both authority and received wisdom.”44 According to writer Nathan Rabin: “The times were changing outside the ballpark, but the major-league mindset seemed stuck somewhere in the mid-’50s. The old guard still ruled with crew cuts, knee-jerk patriotism, reactionary politics, and a near-religious belief in… maintaining the status quo.”45

MLB officials pressured, if not required, players to wear their hair short to counter the hippies of the period. According to Bouton: “If the choice for a pinch hitter or a relief pitcher was between a long-haired guy and a short-haired guy, the [latter] would get into the game.” But, Bouton explained, in the broader society, everything was being called into question. “All the assumptions…rules…ways of doing things, [the era] tossed them all up in the air, and forced people to take another look.…I don’t think it occurred to me that, ‘Gee, all these other people are kicking up a fuss, maybe I should write a book that does the same thing.’ [B]ut you are a part of your environment.”

According to sociologist Elizabeth O’Connell, Ball Four may have advanced the cause of women by challenging America’s masculine ideal. Previous sports books were hagiographies, “reinforcing Horatio Alger myths of self-made men who through dedication and determination were able to rise above their circumstances and become American heroes.” Instead, Ball Four portrays many players as adolescent adults who never matured: what psychologists call the “Peter Pan Syndrome.” “It’s an emasculating text, presenting players as boys who never grew up,” according to O’Connell. “By opening the clubhouse doors to the public and allowing the reader to see the reality of ballplayers’ lives, Bouton contradicted the concept of the male athletic body symbolizing strength of character.”46

With his baseball career apparently ended in 1970, Bouton became a television sportscaster in New York for WABC and then WCBS. Not surprisingly, he was also regarded as a maverick in his new profession. He refused to waste time reading the scores of games during his newscasts, recognizing that fans could get those in the newspaper. Rather than catering to the high-profile professional teams, he focused instead on lower level and lesser known sports, and didn’t just report but also participated, such as in roller derby matches or rodeo events. He urged people to play sports rather than merely watch them.

In 1971, Bouton published a second book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, mostly describing the reaction to Ball Four.47 Bouton made no apologies and expressed his view that sports should be part of ongoing consciousness-raising: “[A]thletes and entertainers have a special obligation to take a stand on issues of the day. In our profession, we tend to be tranquillizers for a whole nation. We contribute to a false feeling of well-being [when instead] we have a responsibility to let people know that, even though we are playing games, we are also aware of problems outside the ball fields.”

Bouton kept pitching in various adult leagues in New Jersey in the early 1970s, while continuing his journalism career. Then, in 1973, he got a phone call from actor Elliott Gould, with whom he had become friends after they met at an anti-war rally in New York and played pick-up basketball games together. Gould told him that he’d persuaded director Robert Altman to give Bouton the part in the film The Long Goodbye that Stacy Keach had been slated to play before he got sick. Bouton got respectful reviews for his acting debut. (The film was also noteworthy for an uncredited appearance by an unknown body-builder named Arnold Schwarzenegger). In 1976, Bouton also starred in a TV sitcom called Ball Four, playing a ballplayer named “Jim Barton” who was also a writer with a preoccupation with his teammates’ personal lives. The show was canceled after only five episodes.

But Bouton gave up his lucrative television career and budding acting career to pursue a baseball comeback. “I decided that my day to day happiness is more important,” he explained at the time.48 In 1975 he joined the Portland Mavericks in the independent Northwest League, earning $400 a month, the same as his teammates. He went 4–1 with a 2.20 ERA.

The Knoxville Sox in the Southern League signed Bouton in 1977, but things didn’t go well. His pitching improved when he moved to Durango in the Mexican League, and he finished the year back with the Portland Mavericks, compiling a 5–1 record. That success brought him back to the Southern League in 1978, this time with the Savannah Braves. He pitched well, going 11–9 with a 2.82 ERA.

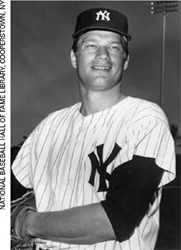

Bouton pitched so well that the Atlanta Braves called him up later in the 1978 season, and at age 38, his comeback was complete, eight years after his initial retirement. He started five games and was 1–3 with a 4.97 ERA. Bouton could have returned with Atlanta in 1979, but he retired instead, having nothing left to prove to himself. In ten major league seasons he was 62–63 with a 3.57 ERA. He continued pitching competitively into his fifties.

When Bouton pitched for Portland in 1977, players were chewing tobacco and getting sick. One of his teammates, Rob Nelson, observed: “Too bad there isn’t something that looks like tobacco but tastes good like gum.” Bouton responded: “Hey, that’s a great idea. Shredded gum in a pouch, call it Big League Chew and sell it to every ballplayer in America.”

Bouton didn’t think any more about it, but after returning home at the end of the season, he remembered it and called up Nelson. Bouton put in the start-up money, contacted an attorney, and sold the idea to the Wrigley Chewing Gum Company. A big hit, the company has sold more than 800 million pouches since 1980 and it won a health and safety award from Collegiate Baseball Magazine for creating the first healthful alternative to chewing tobacco, no doubt sparing many ballplayers from mouth cancer. Bouton also coauthored a baseball murder mystery, Strike Zone.49 He would go on to update Ball Four three times, publishing new editions in 1981, 1990, and 2001, each time adding to his story.

Over the years, Bouton tried several times to make peace with Mickey Mantle, but not until Bouton sent a condolence note after Mantle’s son Billy died of cancer in 1994 did Mantle contact him. The two former teammates reconciled not long before Mantle’s death in 1995.50 For almost 30 years, the Yankees barred Bouton from participating in their annual Old Timers games. But in 1998, the Yankees ended their boycott, finally inviting Bouton back for that celebration. Bouton pitched one inning, enjoying an emotional reunion with fans and some old teammates.

But Bouton wasn’t finished protesting. In 2000, a Cuban boy, Elian Gonzalez, and his mother shipwrecked trying to enter the US from Cuba, and she drowned. The Clinton administration took custody of Gonzalez, intending to return him to his father, who wanted his son back with him in Cuba. But right-wing Cubans in Miami—a powerful political force—wanted him kept in the US as a rebuke of Fidel Castro. Several Cuban ballplayers launched a one-day walkout to oppose the return, and Commissioner Bud Selig backed the move. Having previously rejected political activism by ballplayers, MLB was suddenly claiming its support was a matter of “social responsibility.”

Bouton called out MLB’s hypocrisy. MLB had consistently refused to speak out against injustices such as the Vietnam War and South African apartheid and was now pretending to take a stand. The players were “once again exhibiting typically sheeplike behavior,” Bouton observed. “Cuban players are not acting from political courage but from fear of reprisal from their own community.”51

In 1978, eight years after his initial retirement from major league baseball, Bouton made a comeback with the Atlanta Braves. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

In 2001, Bouton learned that an old ballpark in Pittsfield, near his home in western Massachusetts, would be abandoned in favor of a new field, to be built in the city’s downtown. Wahconah Park wasn’t just any ballfield. It was (and still is) one of the oldest minor league ballparks in the US and among the few remaining wooden grandstand fields. Although the ballpark was built in 1919, ballgames had been played on that spot as far back as 1892. Bouton decided to step in to save the stadium, and renovate it not with public money but by selling shares to ensure ownership by local fans of the team. The plan generated strong public support, but local media, politicians, and business leaders wanted taxpayers to fund a new ballpark on the site of an abandoned General Electric factory that the federal government had determined was a toxic waste dump.

Pursuing his campaign, Bouton discovered that in the previous 15 years, $16 billion of taxpayer money had been spent on new stadiums, replacing more than 100 older, beloved ballparks, “because baseball’s powers-that-be can get away with it. They have a monopoly, granted by the federal government, and they use it to bludgeon local governments to bid against each other for the right to teams.”

“These owners are capitalists who don’t want capitalism,” Bouton explained. “When sports owners don’t have to use their own money to build stadiums and make enormous profits—when American taxpayers subsidize these wealthy owners—it’s massive corporate welfare.”52

To address not only his Wahconah Park experience but also these broader ballpark issues in the US, Bouton turned his extensive notes into a book, Foul Ball: My Life and Hard Times Trying to Save An Old Ballpark.53 He had a contract with a publisher, PublicAffairs, and was ready to launch a 16-city tour to promote the book in 2002. Before publication, however, the publisher told Bouton he would have to delete his discussion of General Electric or the book would be dead. Shocked at the publisher’s complicity, Bouton instead created his own publishing company, Bulldog Press, and released the book on his own in 2003 at a considerable cost to himself. Lyons Press published an updated version in 2005.

Local political and business leaders in Pittsfield undermined Bouton’s restoration and public ownership plan. The town ultimately lost minor league baseball, but he still fought to keep the game alive at the old ballpark. From baseball historian John Thorn, Bouton learned that Pittsfield had the additional attraction of having been one of the oldest places where baseball was known to have been played in the US, dating back to 1791.

In response, Bouton helped create the Vintage Base Ball Federation, bringing nineteenth century baseball rules, uniforms, and atmosphere to cities and towns across the nation. Bouton arranged a vintage baseball game at Wahconah Park on July 3, 2004, when a record crowd of 5,000 fans watched a contest between the Pittsfield Hillies and the Hartford Senators. ESPN Classic telecast the game live for over four hours, billing it as “America’s Pastime: Vintage Baseball Live.” The network commentators included baseball historians John Thorn and David Pietrusza, Bull Durham actor Tim Robbins, as well as Bouton and former major league pitcher Bill “Spaceman” Lee. Bouton and Lee each pitched an inning in the game.

Despite his setback in Pittsfield, Bouton remained active on the stadium issue. After the Montreal Expos became the Washington Nationals in 2005, the new owners persuaded Washington city officials to subsidize construction of a new stadium, Nationals Park. Bouton was outraged, claiming it was bad enough that a profitable ball club would rip off the public but it was even more appalling in an economically troubled city: “How anyone could walk through the public schools of Washington, DC, and then say that paying for a new professional baseball stadium should be that city’s priority, amazes me.”54

In 2004 Bouton appeared in Brooklyn to support the Prospect Heights Action Coalition in its efforts to block another taxpayer-funded stadium proposal that would destroy historic buildings.55 With the support of New York City’s political establishment, including Mayor Michael Bloomberg, billionaire developer Bruce Ratner’s company Forest City Ratner sought to bulldoze homes and small businesses belonging to hundreds of families to make way for what eventually became the Atlantic Yards project, which included Barclays Center, an indoor arena that is now the home to the NBA’s Nets, the New York Islanders of the National Hockey League, and the New York Liberty of the Women’s National Basketball Association.

Calling the proposal’s tax abatement provision “corporate welfare,” Bouton decried the same “fuzzy financing” and “secret meetings” he had encountered in Pittsfield. “You’re not alone, this is an issue nationwide,” Bouton told the crowd. “If this stadium gets built, 20 years from now you’ll hear: ‘These [celebrity architect] Frank Gehry stadiums are out of date. So we’re going to be leaving Brooklyn for another place with a [post-9/11 World Trade Center architect, Daniel] Libeskind stadium.’ Don’t let it happen.”

The same year, after the US launched an illegal, preemptive attack on Iraq, Bouton spoke out against the war. “I opposed it,” recalled Bouton, “because although the US had the means to be successful militarily…[ w]e didn’t have nearly enough understanding of that country’s language and culture, just like in Vietnam. In the US, our rocket science is way ahead of our social science.”56

Handicapped by a stroke in 2012, Bouton announced in 2017 that he had cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a brain disease. He died two years later at age 80 at his home in western Massachusetts.

Bouton did not set out to be a literary or political revolutionary. As he recalled, he grew up as a “conservative kid”57 and viewed himself as an “old fashioned guy.” He ended Ball Four observing: “You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”58

PETER DREIER teaches politics at Occidental College. ROBERT ELIAS teaches politics at the University of San Francisco. Their books, Baseball Rebels (University of Nebraska Press) and Major League Rebels (Rowman & Littlefield), will be published in April 2022.

Notes

1. Karl E.H. Seigfried, “Jim Bouton, Pray for Us,” The Wild Hunt, August 24, 2019 https://wildhunt.org/2019/08/column-jim-bouton-pray-for-us.html.

2. Jim Bouton, with Leonard Shecter, Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues (New York: The World Publishing, 1970).

3. New York Public Library, Books of the Century, https://www.nypl.org/voices/print-publications/books-of-the-century.

4. Time Magazine, “All-Time Greatest Non-Fiction Books” https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/12719.Time_Magazine_s_All_TIME_100_Best_Non_Fiction_Books. In contrast, in 2001 the Baseball Reliquary, a Pasadena-based non-profit organization that Bouton called “the people’s hall of fame,” inducted him into its Shrine of the Eternals and in 2009 hosted a celebration of Ball Four’s 40-year anniversary that included Bouton and his former Seattle Pilots teammates Greg Goossen and Tommy Davis.

5. William Ryczek, Baseball on the Brink: The Crisis of 1968 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 95.

6. John Thorn, “Jim Bouton Interviewed,” Our Game, July 16, 2019, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/jim-bouton-interviewed-2d0930e2ecb9.

7. Joan Mellen, “Jim Bouton,” in Cult Baseball Players—The Greats, the Flakes, the Weird, and the Wonderful, ed. Danny Peary (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 160.

8. Terry Gross, “Jim Bouton Destroys Illusions About Baseball,” Fresh Air, December 8, 1986. https://freshairarchive.org/segments/jim-boutondestroys-illusions-about-baseball.

9. Stan Grossfeld, “Jim Bouton Still as Opinionated as Ever,” Boston Globe, July 18 2014, https://www.bostonglobe.com/sports/2014/07/17/catching-with-ever-opinionated-jim-bouton/ynmwU7CYTMS2qveyeSh3KJ/story.html.

10. Anthony D. Bush, “Knuckleball on Paper: Jim Bouton’s Effect on Sports Autobiographies” Presented at Society of American Baseball Research Seymour Medal Conference, Cleveland. April 17, 1999, www.gpc.peachnet.edu/~dbush/bouton.htm.

11. Mellen, “Jim Bouton,” 161.

12. Jim Bouton, Ball Four: The Final Pitch (New York: Turner Publishing, 2014), 147–48.

13. Mitchell Nathanson, Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020).

14. Mellen, “Jim Bouton,” 158.

15. Even star players didn’t earn enough during the season to make ends meet. In his Hall of Fame Induction speech, Nolan Ryan mentioned working in a gas station during the winter. Jim Palmer got an $11,000 World Series bonus after the Orioles won the 1966 World Series, and still had to take a job in a department store selling suits to cover “groceries, hot water, and electricity.” Loren Kantor, “When Ballplayers Had Offseason Jobs,” Medium, August 13, 2020. https://medium.com/buzzer-beater/whenballplayers-had-offseason-jobs-66bba31cecb2.

16. Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ballgame (Chicago: Ivan Dee Publishers, 2004), 85.

17. Matt Schudel, “Jim Bouton, Baseball Pitcher Whose ‘Ball Four’ Gave Irreverent Peak Inside the Game, Dies at 80,” Washington Post, July 10, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/jim-boutonbaseball-pitcher-whose-ball-four-gave-irreverent-peek-inside-the-game-dies-at-80/2019/07/10/f73acf52-b4e5-11e7-9e58-e6288544af98_tory.html.

18. John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball: How the 1960s Collided with the National Pastime. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 38.

19. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 39.

20. Ryczek, Baseball on the Brink, 101–02.

21. Ron Kaplan, “The Legacy of Ball Four,” Huffington Post, May 25, 2011, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/ron-kaplan/the-legacy-of-ballfour_b_709682.html.

22. Jim Bouton, “Returning to the Minors,” Sport, April 1968: 30.

23. Dave Zirin, “A Q&A With the Late, Great Jim Bouton,” The Nation, July 12, 2019, https://www.thenation.com/article/jim-bouton.

24. Zirin, “A Q&A With the Late, Great Jim Bouton.”

25. Steve Treder, “THT Interview: Jim Bouton,” The Hardball Times, January 10, 2006, https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/the-tht-interviewjim-bouton.

26. Jim Bouton, “A Mission in Mexico,” Sport. August 1969: 35.

27. Leonard Shecter, “Jim Bouton—Everything In Its Place,” Sport, March 1964: 71–73.

28. All-Star pitcher Tom Seaver was another white ballplayer who spoke out against the Vietnam war. See Kelly Candaele and Peter Dreier, “Tom Seaver’s Major League Protest,” The Nation, September 11, 2020. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/tom-seaver-vietnamprotest.

29. David Keyser, “Baseball Ball Four,” Harvard Crimson, October 13, 1970, http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1970/10/13/baseball-ball-fourworld-publishing-company.

30. Jim Brosnan, The Long Season (New York: Harper & Row, 1960).

31. Steve Chawkins, “Jim Brosnan Dies at 84; Relief Pitcher Wrote Inside Look at Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 2014, https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-jimbrosnan-20140707-story.html.

32. Stan Hochman, “Life Writes Bouton a New Ending to ‘Ball Four’,” Philadelphia Daily News, December 7, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

33. Dick Young, “Young Ideas” Daily News, May 28, 1970: C26; Ryczek, Baseball on the Brink, 181.

34. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 183.

35. Jim Bouton, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally (New York: William Morrow, 1971), 137.

36. John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball: How t he 1960s Collided with the National Pastime (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 183.

37. Robert Lipsyte, “Sports of the Times,” The New York Times, June 22, 1970: 67.

38. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 186–87.

39. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 187.

40. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 188.

41. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 189.

42. Ryczek, Baseball on the Brink, 178–79.

43. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 190.

44. John Thorn, “Jim Bouton: An Improvisational Life,” Our Game. December 16, 2016, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/jim-bouton-an-improvisationallife-5237aa5d438a.

45. Nathan Rabin, “Jim Bouton’s Ball Four,” April 17, 2009, https://www.avclub.com/jimbouton-s-ball-four-1798216529.

46. Elizabeth O’Connell, “Now Batting, Peter Pan: Jim Bouton’s Ball Four and Baseball’s Boyish Culture,” in The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2007–2008, ed. William Simons (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2009), 61–78; see also: Ron Briley, Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-Up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), 308.

47. Jim Bouton, with Leonard Shecter, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally (New York: William Morrow, 1971).

48. Paul Goldman, Peter Dreier, and Mimi Goldman, “Jim Bouton Follows His Dream,” In These Times, September 28–October 4, 1977

49. Jim Bouton and Eliot Asinof, Strike Zone (New York: Viking, 1994).

50. Zirin, “A Q&A With the Late, Great Jim Bouton.”

51. Miles Seligman, “The Boy-cotts of Summer,” Village Voice, May 20, 2000, https://www.villagevoice.com/2000/05/02/sports-27.

52. Ted Miller, “Jim Bouton Still Brings It With Gusto from the Inside,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 30, 2006, https://www.seattlepi.com/sports/baseball/article/Jim-Bouton-stillbrings-it-with-gusto-from-the-1207789.php.

53. Jim Bouton, Foul Ball: My Fight to Save An Old Ballpark. (Great Barrington, MA: Bulldog Publishing, 2010).

54. Treder, “THT Interview: Jim Bouton.”

55. Deborah Kolben, “Jim Bouton Cries ‘Foul’ Over Arena,” Brooklyn Paper, January 10, 2004, https://www.brooklynpaper.com/jim-bouton-criesfoul-over-arena.

56. Treder, “THT Interview: Jim Bouton.”

57. Florio and Shapiro, One Nation Under Baseball, 183.

58. Bouton, Ball Four: The Final Pitch, 397.