Baseball Cartoon Memories

This article was written by Robert Cole

This article was published in 1983 Baseball Research Journal

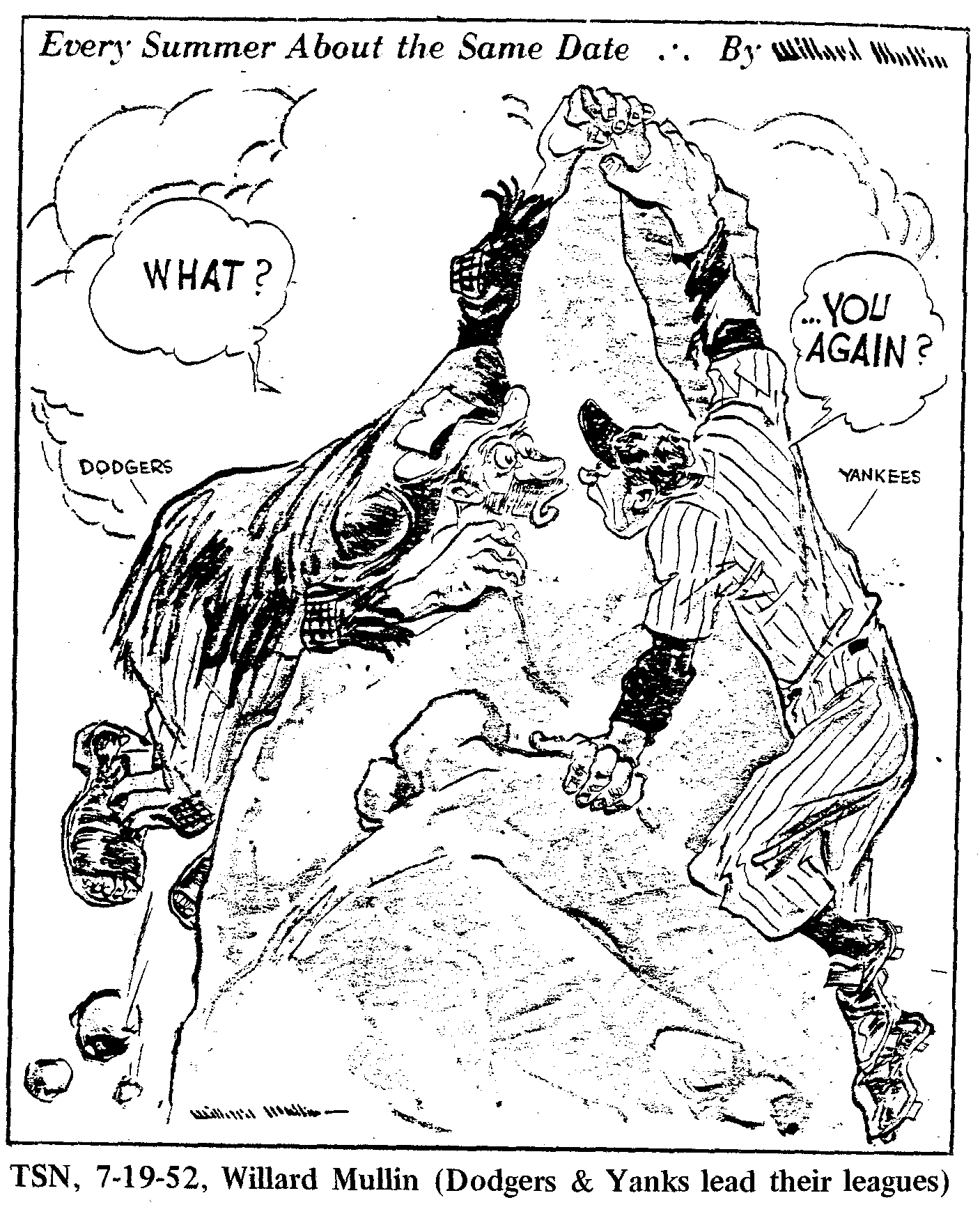

Red Smith wrote of Willard Mullin, the cartoonist: “There is no estimating how many sports columns were inspired by his sketches.” Likewise, it would be difficult to overestimate the influence of sports cartoonists on our memory of baseball from the 1940s and 1950s. The cartoonists created many of the best-remembered images from that era of the game. The dominant illustration on the front page of The Sporting News almost every week from the 1940s to 1964 was a four-column cartoon, and most newspapers then illustrated their sports pages with syndicated cartoons, not the later popular wirephotos. Since only a small percentage of fans were fortunate enough to have easy access to major league ball parks, and to see the players and teams, much of the pre-TV imagery of baseball is from cartoons. When I think of the Brooklyn Dodgers, I think of Mullin’s Bum. The Indians, my favorite team, come to mind because of the Wahoo Indian head they wore on their uniform.

Because they were featured on the front of The Sporting News more often than other cartoonists, Willard Mullin, Lou Darvas, and Leo O’Mealia were the most prominent in their field at that time, which was during the post-war baseball boom. Following is an analysis of the images and messages these three men drew into the memory of baseball.

September 7, 1949, was the date of my first Sporting News. A weekly tabloid newspaper from St. Louis. Five columns wide. 48 pages. Black and white. At the top of the front page was an eagle, its starred and striped wings spread wide, a long thin pennant in its beak spread the width of the page, “Baseball” inscribed at each end of the pennant. The eagle is perched on the r, t, and i of “Sporting” in The Sporting News. Under that title, a subtitle: “The Base Ball Paper of the World.” Price: twenty cents. There was a quality and tone of fantasy and unreality in this publication probably unequalled in any other sportswriting, factual or fictional. This unreality was created by the wildly metaphorical cartoons, nomenclature, and headlines in the newspaper, which, mixed with the presumably believable boxscores and batting averages, made reading TSN an airy and oscillating experience.

The cartoons were the most obvious symbol of The Sporting News. Page one was almost always monopolized by the four-column cartoon, usually drawn by Lou Darvas, who was then in the middle of 35 years with the Cleveland Press, a Scripps-Howard newspaper, or Williard Mullin of the New York World-Telegram. The first Sporting News I saw, that September of 1949, featured a cartoon by Darvas entitled “Heap Big Medicine.” It showed a scene in the “1st class Yankee Ward” of a hospital, a physician labeled “Casey Stengel” (the likeness was precise) holding a stethoscope to the chest of a patient labeled “Tommy Henrich” in a cranked-up hospital bed. The patient’s feet are sticking out from under his cover and over the end of the bed, in the larger-than-life way the athletes usually were presented in these drawings. The vital-signs chart, also labeled “Henrich, Tom,” shows a plummeting line graph. To the right of the bed is a man labeled “Yogi Berra,” wrapped in a blanket, with a glowing thermometer in his mouth, and seated in an undersized wheelchair. The physician has a bag full of saw, hammer, and the inevitable pills in these injury drawings – “sore shoulder pills,” “pitching pills,” and “heel pills.” The physician is looking back over his shoulder at the door, where an Indian is leaning with a malevolent grin, three scalps labelled “Williams,” “McCarthy,” and “Stephens” swinging from his left hand, and a tomahawk half-hidden behind his back in his right hand. The Indian is saying “Uh-h-h. . . what’s up, Doc?” – borrowed from Bugs Bunny — and the physician is saying, “What th’ . . . is that guy here again?”

Translated, the cartoon is saying simply that the New York Yankees, managed by Casey Stengel and weakened by injuries to two of their star players, Henrich and Berra, now must face the challenge of playing the Cleveland Indians, who have just won three straight games from the Boston Red Sox (represented by the scalps of Joe McCarthy, their manager, and Ted Williams and Vern Stephens, two of their stars). Readers are assumed to know that this is an image of the situation in the American League pennant race. TSN is very much an insider’s newspaper. But to well informed sports fans, much of what the publication had to say was simple, obvious, overstated, unanalytical, even a little dated; the trick of the cartoonists and correspondents was to find a fancy or roundabout way of saying it, and they usually accomplished this with a lot of indirection, repetition and rhetoric. The subjects, concepts, and symbols in the paper were so abstracted and exaggerated in the cartoons and headlines that to look long at one or to think much about it was to find yourself floating into a world at several removes from reality. All you could hold to were the simple facts that were the bases for the writer’s or editor’s or artist’s exercise in the peculiar high style and convention and bizarre metaphors of TSN.

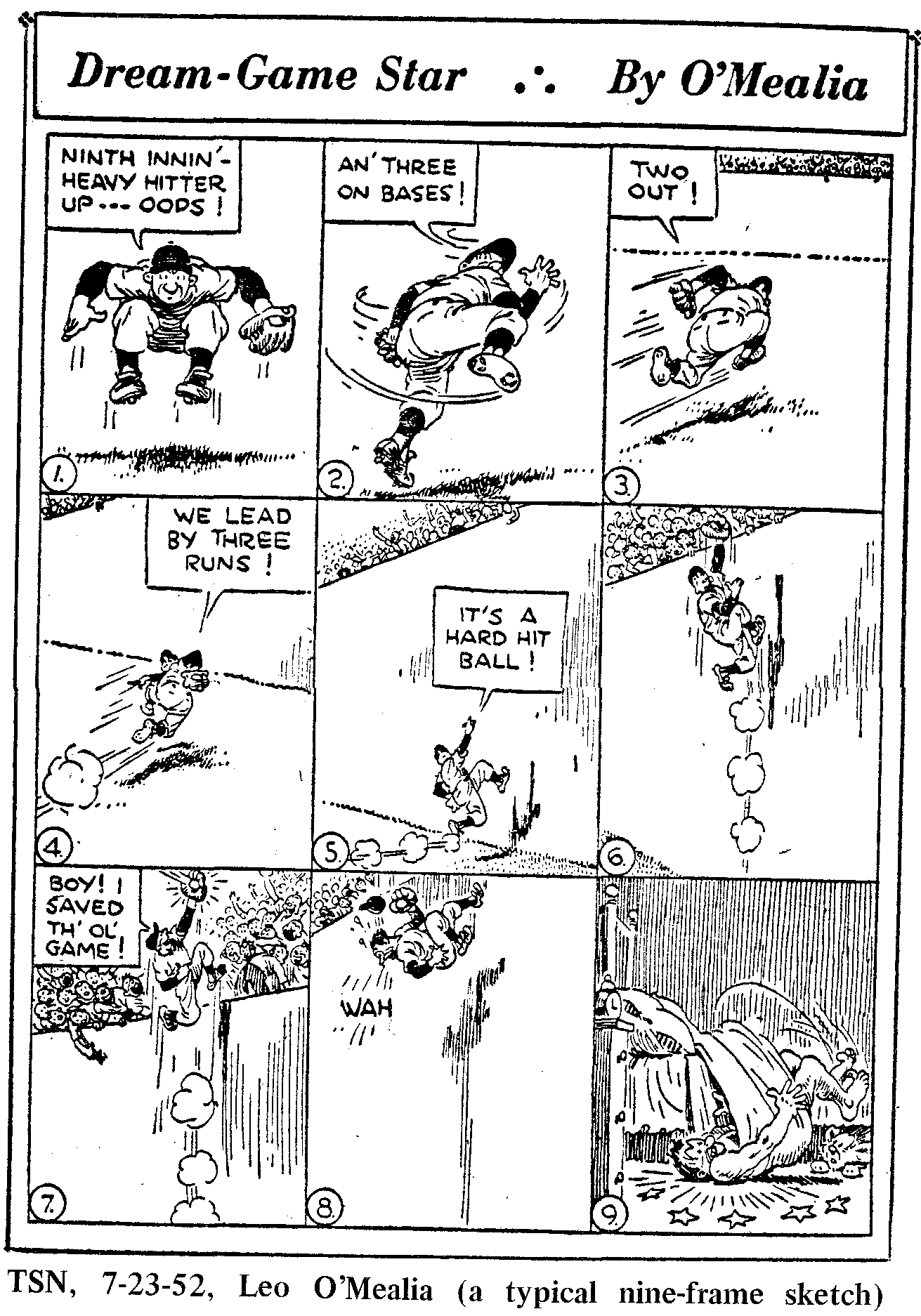

Most of the cartoons were topical, depicting trends and events from week to week in the big leagues, and static in design, with the characters usually talking, either sitting or standing. If they were moving, it was without motion lines, so that they looked like statues. A third cartoonist who often appeared was totally unlike Mullin and Darvas: Leo O’Mealia of the New York Daily News. O’Mealia’s cartoons were usually run smaller, in two columns on inside pages, and usually were six or nine frames illustrating the sequence of definitive motions of ballplayers batting, fielding, and pitching – leading up to a failure by a boasting player. The players were representative, not specific people, their actions generic, not associated with particular players. O’Mealia drew the game.

Mullin was the most famous of the three. I had seen his drawings in sports magazines, in ads, in books. He seemed to make a sports story official. He gave status. His best known figure was his Brooklyn Bum (which O’Mealia contended that Mullin had stolen from him, according to people at the Daily News) the ragged, pot-bellied, rubber lipped hobo who represented the Brooklyn Dodgers, but Mullin’s characterizations of the St. Louis Browns and other National League contenders were familiar and funny, too. The Boston Brave was a bony, breech-clothed, one-feather Indian, somehow less self-confident than the one in Cleveland. The New York Giants was a huge-bottomed, narrow-shouldered, blank-eyed blob who blundered around in murderous innocence.

The St. Louis Cardinals were a riverboat gambler – the St. Louis Swifty, a pun on their baserunning – with a beaver hat, rat-tail mustache, flowered cravat or string tie, double-breasted long coat, and habitual sneer. The Phillies, in honor of their unusually young team of bonus players, became a stripe-shirted, stogie-smoking juvenile delinquent in Mullin’s 1949 drawings. Before then, he drew the Phils as a plump old Quaker gentleman. The Pirates were obvious, but the Browns, instead of being brownies, were a sleepy, whistle-lipped Missouri hillbilly, wearing a scraggly Van Dyke beard, tall cone hat, polka-dot shirt over long flannels, and long boots. Lou Darvas created no such memorable characters, and was often more contrived than Mullin, but he and Mullin used the same subjects and motifs so interchangably it was hard to tell if one might be copying or parodying the other. For instance, they both would often draw characters around a table, gathered either to eat or play cards, to show that the characters had a common interest, such as club representatives going to a winter convention, or to show that they were guests who had been invited or qualified, like Mullin’s pitchers trying to dine at the “20 Club” (October 11, 1950). To get in, they had to win 20 games. Mullin showed three pitchers — Bob Lemon, Vic Raschi, and Warren Spahn – in the background, seated and ordering. One of Mullin’s recurrent snooty waiters is saying to them, “May I suggest the hassenfeffer?” In the foreground several other pitchers – Preacher Roe, Don Newcombe, Art Houtteman, Ed Lopat, Vern Bickford, Johnny Sam, Robin Roberts, Larry Jansen – are outside the roped-off dining area, waving cards labeled 18 and 19 (victories) at two more snooty waiters, one of whom is saying, “Do you have reservations, sir?” The cartoon is entitled, “Still Very Exclusive.” Mullin drew on this theme every year.

Mullin and Darvas also used a gallery or portrait motif to depict honors earned. Late in the 1951 season they used it three times in less than a month. On August 29, Mullin showed workmen hanging Bob Feller’s portrait over a mantle in the 20 Club. He had done that one with Mel Parnell in 1949. On September 12 Darvas reviewed the Yankees’ notorious practice of buying a key substitute on waivers late in the season by showing pictures of Bobo Newsom (1947), Johnny Mize (1949), and Johnny Hopp (1950) above a scene from this season of Yankee executives pulling Johnny Sam out of a hat labeled “waivers.”

The metaphor was mixed, as was often the case in Darvas cartoons, because the primary image was that of a stage magician. Two weeks later Darvas used the portrait motif ironically: he drew a frame labeled “1951 Phillies” around a scene of Phillie Manager Eddie Sawyer and Mullin’s juvenile delinquent flanking an empty throne that held the sign, “Reserved for Curt Simmons.” Simmons, the Phillies’ star lefthander, received considerable attention when he was called up with his National Guard unit in August 1950 after already having won 17 games and helping the Phils to the National League lead. The cartoon is saying the 1951 Phillies lost the throne (pennant) and won’t return to it until Simmons returns from service. This drawing recalled the one Mullin had done October 4, 1950, in which the old Quaker is proudly showing the juvenile a portrait of an old-time ballplayer labeled, “Phillies 1915” (the last Phillie pennant before 1950), to inform the boy of his heritage. Leaning against the left margin of the drawing is an unusually skinny Brooklyn Bum, labeled “the beat generation.”

Another memorable cartoon on Curt Simmons was by Leo O’Mealia, entitled “Curt Response” (August 16, 1950). It showed Simmons in a Pennsylvania National Guard uniform (with the state symbol keystone on his helmet), carrying a rifle and handing in his Phillies ballcap and saying, “I’ll be in there pitching’!” In the background is a harmless little Quaker, rubbing his chin sadly, his Pennant Hopes flag dragging on the ground beside him.

The dream or nightmare motif was another that Mullin and Darvas used. The first one I saw was by Darvas in September 1950, called “Indian Lullaby.” It showed Manager Lou Boudreau tossing in his undersize hotel bed, recalling the Indians’ worst failures and his most embarrassing remarks of the season: “I feel confident we are going to win the pennant . . . Indians lead Red Sox 7-0, then lose 11-9! Indians lead Red Sox, 12-1 . . . then lose, 15-14!” (I was suffering with him.) Other times, Darvas showed pitchers dreaming in terror about the small size of the strike zone in 1949, and Mullin showed them having nightmares over the new balk rule in 1951. Mullin varied the theme in May 1950 by having the Phillie brat blow smoke dreams from his cigar – dreams of pitchers Robin Roberts and Curt Simmons.

One of their more interesting motifs was that of the pennant or world championship symbolized as a girl being pursued by a contending team. It appeared three times late in the 1951 season. On July 25 Mullin showed the suffering Yankees, cap in hand, going to the Brooklyn Bum for advice to the Lovelorn. Bumy, behind his desk, is surrounded by pictures of Miss First Place. He says to the Yank, “Havin’ trouble keepin’ th’ goil frien’, huh?” The Yank replies, “Yes . . . We used to go steady . . . but she keeps returning m’ ring and goin’ out with the guy from Chicago . . . An’ now that rich bird from Boston is giving her a rush . .” “Allus yez needs is poisonality, poiseverance, pitchin’ an’ a few base hits,” Bummy advises.

September 5 Darvas shows Casey Stengel mesmerizing Miss Pennant, who, little dots around her head, her eyes baggy, arms outstretched, is walking to him in a trance, saying, “The `miracle manager’ is calling again.” When the Yanks win, Mullin on October 3 has the pinstriped hero carving “51” into a tree while “Miss World’s Champ,” hands clasped and wrists turned inside out in the anxiety of infatuation, fawns over him. Other numbers have been carved on the tree: `50, `49, back to `21. The Yank is saying, “You-m-me, huh, kid? Let’s go steady again!”

Four other memorable Mullins were “Under the Lights” (February 8, 1950), “Fortissimo” (August 6, 1950), the arcane “Chinaman’s Chance” (June 14, 1950) and “The Big One That Got Away” (December 19, 1951). “Under the Lights” shows a ballplayer labeled “Majors” seated under presumably intense lamps, staring into them as he is being grilled by four investigators, who are asking, “Where were you on the night of April 18th? . . . Where were you on the night of May 6th? . . . May 16th? . . . The night of June third, fourth, fifth, and sixth? . . . July 23rd? . . . On the night of August 10th?” The player gives one answer, “Playin’ ball!” In one corner of the drawing is a note, “News item . . . major leagues to play record 409 night games in 1950.”

“Fortissimo” has the Giant booby seated at a concert piano, banging out “Runnin’ Wild,” in honor of the Giants’ strong run for the pennant. Three other contenders – the Brave, Phillie, and Swifty – are clustered in the foreground, wincing and covering their ears. The bum is huddled with them, looking big-eyed and annoyed and sucking hard on his cigar.

“Chinaman’s Chance” is a stew of metaphors, illustrating a story, “Major Hitters Swinging for Homer Marks.” The cartoon shows an oriental character in a Mandarin jacket and rice-basket hat walking down a path of pitchers laid out like railroad ties. The Oriental is labeled “the Chinese homerun,” and he carries on his shoulder a bamboo pole with a basket at each end, one basket holding “the gopher ball,” the other holding “the rabbit ball.” This is an ornate way of saying that a combination of a souped-up (rabbit) ball, short-distance (Chinese) home runs, and easy-to-hit (gopher) pitches is oppressing pitchers.

“The Big One That Got Away” is as simple as the Chinese-homer drawing is contrived. It shows some large sea creature, either a fish or a shark, with a head like Ted Williams’, swimming untouched among several trade-baited hooks, lines, and sinkers – meaning that no team had been able to make a trade with the Boston Red Sox for Williams.

Except for occasional drawings like the Curt Simmons mentioned above, Leo O’Mealia’s best work in TSN was not topical but archetypal, sequences of what the ballplayers did on the field, or what they did in the off-season. Many of these were included in a gem of a dime booklet published by the Daily News in 1950 called “Leo’s Sports Cartoons,” illustrated on the cover by the lion cub with the surprised grin that O’Mealia sketched into the last frame of most of his strips. O’Mealia’s most common theme was “the best-laid plans . . .” – that egotistical expectations and careful planning and execution on the diamond all have unexpected results. For example, “There’s A Catch To It,” printed in TSN November 9, 1949, and on other occasions, shows a nine-frame sequence of a pitcher’s windup and delivery: he comes set . . . stretches . . . pumps back . . . pumps forward . . . pivots . . kicks. . . kicks. . . throws – “Crack” . . . the ball comes back, as he follows through . . his eyes bug out and his cap flies off as he sees the ball glowing in his glove. It is the typical O’Mealia contrast between the careful, almost contorted preparation, and the random, unpredictable result.

O’Mealia was sensitive to the difference between rookies and veterans, and judging by the apparent age of many of his players, seemed a little partial to veterans. One of his favorite sequences was the unexpected result for the aggressive rookie: A young outfielder hitches up his pants and says, “I’d like to show up some of these ol’ guys” . . . He goes sprinting after a fly: “I’ll show `em some speed.” . . . Passes another fielder: “I made `at ol’ fellow look like he was stand’ still!” . . . Extends full length to make the catch: “I’ll show `em!” The old-timer yells, “Double th’ guy off second, kid!” . . . Rookie plants his foot to pivot and throw: “Now I’ll show `em a throwin’ arm!” Old-timer behind him: “Nice catch, kid!” . . . Rookie rears back to throw, and ball flips out of his hand to surprised old-timer: “Ooops! Slipped outta my hand!” . . . Old-timer throws it in: “We got two, kid!” Lion cub is pleased.

Two of O’Mealia’s best were about holdouts. I saw one, “The Holdout,” in the back of the March 15, 1950, issue, and saw it reprinted. It shows a man in a topcoat and hat, shivering in a winter wind and imagining a ball game under the palm trees, the sun shining brightly. The other, “Into Each Life Some Rain Must Fall,” was on page one, January 25, 1950. It showed a postman with a back-bending bag of mail struggling through a heavy rain, carrying a letter for a baseball player and musing about the desirability of the ballplayer’s job: “What a job the ballplayer has. Nothin’ t’ do all winter an’ he – … only works about seven months! … An’ then he only plays for two hours, but only when it ain’t rainin’!” . . . The ballplayer, a bigger man in a fancy robe, answers the door, opens the contract, clasps his hand to his head, and rages, “A five thousand dollar cut??? No, I won’t take it!! I won’t work for a -” The postman looks apprehensive . . . . “Lousy thirty five thousand a year!” The ballplayer slams the door, and the postman and the lion cub keel over backwards in the rain.

The visual impressiveness of these novelty drawings – all of which I remember from boyhood over 30 years ago – can perhaps be suggested by the impact of one of the smaller, unsigned sketches of major-league team symbols. The Sporting News occasionally used them as half-column illustrations in the weekly roundups of each team’s activity. Most of the symbols were innocuous and predictable, such as a Brave or a Cub swinging a bat, nothing as assertive as Willard Mullin’s creations. But the Cincinnati Reds’ symbol was strange: it showed an angry, bearded man in a black hat and long black coat, carrying a bomb in his left hand and a bat in his right. It was a long time before I understood that he represented a Bolshevik (Red) revolutionary. I saw him a number of times in 1950 and found him mysterious. He looked like Bluto in the Popeye comic strip. Then the August 30 Sporting News ran a note in “In the Press Box” saying that the morning newspaper in my hometown, The Beckley (W. Va.) Post-Herald, was going to refer to the Cincinnati team as the Redlegs, not the Reds, because “the common and always-used abbreviation of `Reds’ reminds one of the communistic influence trying to crush out democracy in the world.” By the next spring TSN had changed its team symbol for the Reds from the Bolshevik to a representation of an old-time ballplayer, which was appropriate because the Reds had been the first professional team, back in 1869. By 1953 the Cincinnati team management had run a full-page ad in The Sporting News asking that the team be called the Redlegs instead of Reds, for the same patriotic reasons in that McCarthy Era. I never saw the Bolshevik ballplayer again.

Footnotes to the work of giants like Mullin, Darvas, and O’Mealia could be seen almost every day in the smaller newspapers around the country that during those days could rarely afford illustrations besides the inexpensive syndicated cartoons. One of the artists I was familiar with who was seen by millions of baseball fans but known by few was Alan Mayer of King Features.

As more of the smaller newspapers began to subscribe to wirephoto services, Mayer and other syndicated cartoonists were needed less in the l960s, although Murray Olderman of the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) continued to be published. The sports cartoon was gradually losing its place in the papers, however. Leo O’Mealia died in 1960, and was succeeded by Bill Gallo at the Daily News. Willard Mullin and Lou Darvas were active into the l970s (Darvas retired in 1973 and is now in a rest home). Before all these men, the most famous sports cartoonist in the early years of the century had been T. A. Dorgan (TAD), who influenced O’Mealia. But there never was quite a period of widespread exposure and popularity for sports cartoonists such as Mullin, Darvas, and O’Mealia knew in the 1940s and 1950s.