Baseball Immortals Invade the Cotton Bowl for the 1950 Texas League Opener

This article was written by C. Paul Rogers III

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

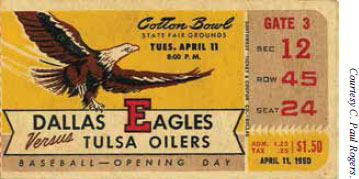

1950 Cotton Bowl ticket. (Courtesy of C. Paul Rogers III)

The Cotton Bowl Stadium in Dallas dates to 1930, when it was known as Fair Park Stadium, since it was built on the State Fairgrounds. Its fame was originally from its hosting of the annual Cotton Bowl football game, which was played there from 1937 until 2009. In the late 1940s the Cotton Bowl was also commonly referred to as “The House that Doak Built” because the demand to watch SMU’s triple-threat running back Doak Walker necessitated adding a second deck on both sides to increase capacity to over 75,000.

For one night in 1950, however, the Cotton Bowl was also the improbable site of a Texas League baseball game between the Dallas Eagles and the Tulsa Oilers. The game was the brainchild of Eagles flamboyant owner Dick Burnett, who wanted to start the 1950 Texas League baseball season by breaking the minor-league attendance record. By doing so, he hoped to put Dallas on the map for a major-league franchise, since rumors were rampant that several teams, including the St. Louis Browns, were considering relocation. He also hoped that a blockbuster start to the Texas League season would increase local interest in the Eagles and improve attendance for the rest of the season.1

Burnett was an oilman from Gladewater in deep East Texas and had purchased the franchise in 1948 for $550,000 from a group headed by George Schepps. He promptly changed the name of the team from the Rebels to the Eagles and immodestly renamed the team’s ballpark Burnett Field. It held 10,500 people and was located in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas, by the Trinity River just south of downtown.2

The minor-league paid admissions record was supposedly 56,391, set by the Jersey City Giants in their 1941 Opening Day against the Rochester Red Wings.3 That figure was subject to interpretation, however, since the Jersey City ballpark held only 25,000 and there was not a turnstile count of how many actually attended the game.4 Also, Burnett probably was aware that a 1944 Little World Series game in Louisville between the Louisville Colonels and the Baltimore Orioles had drawn 52,833 by actual turnstile count.5

Burnett had already made waves prior to the 1950 season by signing former Chicago Cubs manager Charlie “Jolly Cholly” Grimm at the unheard-of salary of $30,000 to manage the Eagles.6 Although there were many skeptics, Burnett set about trying to break the attendance record by securing nine baseball immortals to take the field to start the game for the Eagles. Burnett started at the top by contacting Ty Cobb, and when Cobb agreed, others quickly committed as well.7 In all he secured Tris Speaker, Dizzy Dean, Mickey Cochrane, Charlie Gehringer, Frank “Home Run” Baker, Duffy Lewis, Travis Jackson, and Grimm, a top-notch first baseman in his playing days, who of course had to be there anyway.8

Burnett pulled out all the stops in promoting the game, enlisting the help of the local print and radio media. He got a big boost early on when the First National Bank purchased 15,000 tickets and distributed them to high-school students in Dallas and Highland Park.9

Opening Day was on April 12, and the day began with a luncheon at the Town & Country Restaurant near downtown, attended by 200 invited guests, including Texas Governor Alan Shivers and the assembled baseball legends.10 Gordon McClendon,president of the Liberty Broadcasting System, served as emcee and interviewed the former players to a national radio audience, asking each what their most memorable moment in baseball was. When it was Ty Cobb’s turn, Cobb told a story and punctuated it with a couple of well-chosen swearwords, prompting McClendon to grab the mike and say, “Oh well, the Liberty Broadcasting System has been on the air now for two years and I guess that’s long enough anyway.”11

After the luncheon, the dignitaries were escorted down a parade route through downtown and out to Fair Park. Game time was 8:00 PM. but most of the crowd of 53,578 fans were there by 6:30 to watch the old-timers take batting practice. They were treated to an assortment of line drives by the 62-year-old Tris Speaker and then a bunting exhibition by Ty Cobb, who was 63. Then Cobb called out to batting practice pitcher Rube Fischer, “Over second base,” and delivered the next pitch on a line directly to center field.12 Cobb and Home Run Baker, who was 64, wowed the crowd with the longest drives into the stands.13

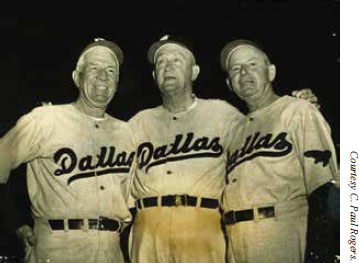

Pre-game Cotton Bowl baseball activities included the appearance of former major-league stars, from left: Tris Speaker, Ty Cobb, and Duffy Lewis. (Courtesy of C. Paul Rogers III)

Pregame festivities began at 7:15 and were elaborate, with bathing beauties from Greenville, Texas, parading around the field in swimsuits buttressed by holsters and six-shooters, and a performance by the Kilgore College Rangerettes, hoisting miniature bats rather than batons. The collegians’ precision and jitterbug dancing reportedly “delighted the crowd.”14

The public-address announcer introduced the old-timers to warm applause as they took the field one by one. Cobb had been first listed as the center fielder, but announced in the clubhouse before the game that he would play right field. “There’s only one center fielder,” he said. “Speaker plays center.”15 Duffy Lewis (age 61) rounded out the outfield in left while the infield consisted of Grimm (age 51) at first, Charlie Gehringer (46) at second, Travis Jackson (46) at shortstop, and Baker at third. Dizzy Dean, a relative youngster at 40, was on the hill pitching to Mickey Cochrane, who was 47.

The layout for baseball was unusual, to say the least. To cram a baseball diamond into the legendary football facility meant that the foul lines to right and left field were only about 200 feet from home plate. Dead center field was probably 500 feet or more away. Special ground rules were put in place so that any ball flying into the stands was a ground-rule double. Also, the only dirt portions of the field were the pitcher’s mound and the batter’s box, but the grass in the basepaths was cut shorter than in the outfield.16

Governor Shivers threw out two first pitches from the mound to batterymate Burnett which “umpire” Dizzy Dean, called strikes although neither was one. Then Tulsa’s Harry Donabedian stepped to the plate to face Dizzy, who had earlier announced that “I’m gonna try to fog it in there and I hope nobody gets kilt.”17 Dean, who had a farm in nearby Lancaster, managed to get two strikes on Donabedian, but then walked him on a full count. Dean, of course, protested vigorously to the home-plate umpire and was tossed from the game. His teammates, in a show of supposed unity, followed Dean to the home dugout, to be replaced by the regular Dallas Eagles.18

Donabedian returned to home plate and batted again, promptly singling against the Eagles’ Tom Finger to officially kick off the season in a game Tulsa won 10-3. The Oilers took advantage of the unusual layout, recording seven ground-rule doubles to three for the Eagles. The Oilers’ young catcher Hobie Landrith was a casualty of the evening when he fractured his ankle sliding into home in the fourth inning.19

While the Eagles were not affiliated with a major-league team, the Oilers were a farm club of the Cincinnati Reds and were loaded with prospects.20 The Oilers’ shortstop, Roy McMillan of Bonham, Texas, debuted with the Reds in 1951 and went on to a 16-year major-league career as one of the best defensive shortstops in the game, making two All-Star teams. Slugging Oilers outfielder Bob Nieman jumped up to the St. Louis Browns in 1951 and played 12 bigleague seasons with a career .295 batting average. And the broken ankle didn’t hold back Hobie Landrith for long, as he had a late-season call-up to the Reds, the start of a 14-year major-league run.21 The Oilers also had the veteran Eddie Knoblauch, who accumulated over 2,000 minor-league hits, mostly in the Texas League.22

Dotting the Dallas lineup were also future major leaguers like the 21-year-old Bob Buhl, who would go on to win 166 big-league games, mostly with the Braves and Cubs, and infielder Billy Klaus, who would have an 11-year major-league career as a utility infielder. The Eagles also featured a number of former big leaguers such as Johnny Beazley, Rugger Ardizoia, Heinz Becker, and Bob Malloy, who were playing out the string. Twenty-five-year-old hurler Wayne McLeland was the team’s outstanding performer as he went 21-8 with a 2.49 earned-run average.23

Burnett’s Cotton Bowl extravaganza was by any measure a great success. He did in fact break the minor-league attendance record measured by people in their seats24 and blew by the Texas League attendance record of 16,018, set in 1930 by the Fort Worth Cats.25 Not surprisingly, Burnett also won the Metroplex attendance battle for the evening as the Cats drew 3,852 to their opener that night in Fort Worth.

Afterward an ecstatic Burnett declared that the turnout proved that Dallas was ready to support a major-league franchise, if only he could get one to relocate.26 That point was perhaps debatable because 24 hours later, the Eagles drew only 1,048 fans back in Burnett Field for their second game of the season, again against Tulsa. Afternoon rains and a chilly wind doubtless had something to do with the poor showing.27

The Eagles, buttressed by their opening throng, drew 317,592 fans for the season, tops in the league. They led the Houston Buffs by about 60,000 fans, which means that if one takes out the Cotton Bowl game, the two major Texas cities were about dead even. But perhaps more telling is that the Eagles outdrew two major-league franchises in 1950. The Philadelphia Athletics drew 309,805 patrons to Shibe Park while the St. Louis Browns attracted only 247,131 to Sportsman’s Park.28 Of course, within four years both franchises, located in two-team cities, moved to Kansas City and Baltimore, respectively, not Dallas or Houston.

Although also known for his volatile temper, Dick Burnett continued to be a progressive innovator, sort of a minor-league version of Bill Veeck. In 1952 he integrated the Texas League when he signed Negro League veteran pitcher Dave Hoskins to a contract. It turned out to be a great move competitively as well as socially as the 34-year-old went 22-10 and, as a sometime two-way player, batted .328 in 62 games to lead the Eagles to Dallas’s first pennant since 1936.29

Burnett was named Minor League Executive of the Year in 1953 by The Sporting News but sadly died of a heart attack in 1955 at the age of 57 while watching his Eagles play in Shreveport. Although he did not live long enough to see major-league baseball come to the Metroplex, he certainly helped set the foundation for what was to come.

The Cotton Bowl, meanwhile, left baseball behind and reverted to its place as one of the preeminent football venues in the country. Not only did it host the annual Cotton Bowl game for 72 years30 but the Red River Rivalry, the annual grudge match between the Universities of Texas and Oklahoma, has been played there every year since 1932. The State Fair Classic, typically between Prairie View A&M and Grambling, is a staple of the State Fair. The Cotton Bowl was for many years the home stadium for the SMU Mustangs and has served as home for three professional football teams, the NFL’s Dallas Texans (1952)31; the AFL’s Dallas Texans (1960-1962),32 and the Dallas Cowboys (1960-1971).

In 1994 the Cotton Bowl playing surface was widened and the venerable old stadium played host to six World Cup soccer matches. Then on New Year’s Day 2020, the annual Winter Classic National Hockey League game was held at the Cotton Bowl as 85,000 watched the Dallas Stars defeat the Nashville Predators. But no one since Dick Burnett has again suggested the revered old stadium for a baseball game.

C. PAUL ROGERS III is co-author or co-editor of several baseball books including The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant Race (Temple University Press, 1996) with boyhood hero Robin Roberts and Lucky Me: My 65 Years in Baseball (SMU Press, 2011) with Eddie Robinson. Paul is president of the Ernie Banks-Bobby Bragan DFW Chapter of SABR and a frequent contributor to the SABR BioProject, but his real job is as a law professor at the SMU Dedman School of Law, where he served as dean for nine years. He has also served as SMU’s faculty athletic representative for 37 years and counting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was edited by David Siegel and fact-checked by Mike Huber.

NOTES

1 The fifth-place Eagles had drawn 404,851 spectators in 1949, tops in the league by well over 100,000 fans. That averaged to about 5,200 a game, but only half-filled Burnett Field. Lloyd Johnson & Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition (Durham: Baseball America, Inc., 1997), 378.

2 Chuck Cox, “Recalling Our Field of Dreams,” unidentified and undated article on file with the author.

3 “Minors’ Paid-Admission Mark Held by Jersey City With 56,391,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1950: 21.

4 James M. DiClerico and Barry J. Pavelec, The Jersey Game: The History of Modern Baseball from Its Birth to the Big Leagues in the Garden State (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1991), 101.

5 Frank Jackson, “Thinking Big in Big D in 1950,” FanGraphs, January 12, 2012, https://tht.fangraphs.com/thinking-big-in-big-d-in-iQ50/.

6 Bill O’Neal, The Texas League 1888-1987: A Century of Baseball (Austin: Eakin Press, 1987), 104-105.

7 Larry Bowman, “Eagles in the Cotton Bowl,” Legacies—A History Journal for Dallas and North Central Texas, Spring 1994: 25.

8 “Diamond Immortals Feature Eagle Opener,” Dallas Morning News, April II, 1950. All but Lewis and Grimm wound up in Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

9 Bowman, 27.

10 Duffy Lewis was the last legend to arrive and missed the luncheon.

11 Bill Rives, “Cobb Quickly Retired as Talker After His Microphone Sizzler,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1950: 22.

12 Bill Rives, “53,578 Cheer All-Time Stars at Dallas Opener,” The Sporting News, April 11,1950: 21.

13 “Diz Thought Barr’s Head Should Rattle,” Tulsa World, April 12, 1950.

14 Rives, “53,578 Cheer All-Time Stars at Dallas Opener,” 22.

15 Kevin Sherrington, “Dallas’ Ty Cobb, if Only for a Day,” Dallas Morning News, April 8, 2012: 2C.

16 Rives, “53,578 Cheer All-Time Stars at Dallas Opener,” 21.

17 Rives, “53,578 Cheer All-Time Stars at Dallas Opener,” 22.

18 Frank Jackson, “Thinking Big in Big D in 1950.”

19 John H. Turner, “54,141 See Cress Hurl Victory Over Eagles,” Tulsa Daily World, April 12, 1950.

20 Tulsa finished in third place in the 1950 Texas League standings with an 83-69 record while Dallas ended up in fifth place in the eight-team league, with a 74-78 won-lost total.

21 In 1961 Landrith gained a certain notoriety when he was the first player selected by the New York Mets in the National League expansion draft.

22 Eddie Knoblauch was the uncle of 12-year major-league veteran second baseman Chuck Knoblauch.

23 McLeland had cups of coffee with the Detroit Tigers the next two years but finished his brief major-league career with an 0-1 record and an 8.56 ERA in 10 appearances.

24 The official tally showed 54,151 tickets sold with an actual attendance of 53,378. Jackson, 5.

25 Harry Gage, “Oilers Clip Eagles, 10-3, in Texas Loop Opener,” Dallas Morning News, April 12,1950.

26 “Opener Shows Dallas Ready for Big Time, Says Burnett,” The Sporting Yews, April 18, 1950: 22.

27 Bill Rives, “Skid From 50,000 to 1,048 Fans in Dallas in 24 Hours,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1950.

28 Johnson & Wolff, 389.

29 Kevin Sherrington, “Breaking Barriers,” Dallas Morning News, May 21, 2000: 28B.

30 In recent years, the First Responder Bowl Game has sometimes been played at the Cotton Bowl around the first of the year.

31 The NFL Dallas Texans became the Baltimore Colts the following year and, after moving to Indianapolis following the 1983 season, became today’s Indianapolis Colts.

32 The AFL Dallas Texans moved to Kansas City after the 1962 season to become the Kansas City Chiefs and, as of 2024, were winners of three of the last four Super Bowls.