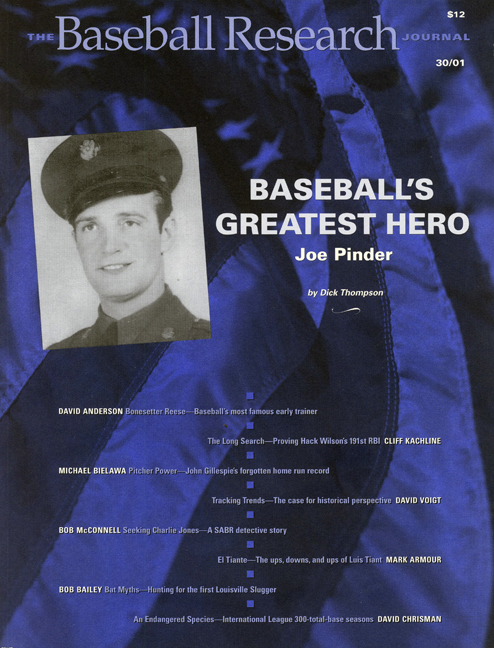

Baseball’s Greatest Hero: Joe Pinder

This article was written by Dick Thompson

This article was published in 2001 Baseball Research Journal

The time was shortly after 7 AM. The place was a stretch of seashore on the Normandy coast of France designated Omaha Beach. The date was June 6, 1944. Less than sixty minutes had passed since H-Hour, when the first wave of men from the 16th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, the only first wave assault unit on D-Day with combat experience, hit the beach.1 A landing craft containing the 16th’s Regimental Headquarters Company was headed for the Easy Red sector of the beach. Among the men in the boat was Technician 5th Grade Joe Pinder.

The time was shortly after 7 AM. The place was a stretch of seashore on the Normandy coast of France designated Omaha Beach. The date was June 6, 1944. Less than sixty minutes had passed since H-Hour, when the first wave of men from the 16th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, the only first wave assault unit on D-Day with combat experience, hit the beach.1 A landing craft containing the 16th’s Regimental Headquarters Company was headed for the Easy Red sector of the beach. Among the men in the boat was Technician 5th Grade Joe Pinder.

Pinder had enlisted right after Pearl Harbor. He had seen action in North Africa and Italy and had been awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge on March 24, 1944.2 Joe Pinder was also a veteran of six minor league baseball seasons. A right-handed pitcher from the Pittsburgh area, he had worked in the Cleveland Indians, New York Yankees, Washington Senators, and Brooklyn Dodgers farm systems. Pinder had notched 17 pitching victories in 1941 but his goal of reaching the major leagues had been put on hold. There was a bigger cask at hand.

Omaha Beach was quickly turning into a disaster. Launched from landing barges still out at sea and designed to swim to shore under their own power, all but five of the thirty-two amphibious tanks expected to provide support for infantry in 1st Division areas sank in the heavy surf.3 Naval fire support had also ceased

so as not co hie American troops landing on the beach. Navy gunners waited anxiously for target co ordinates co be radioed from their fire-control officers who had gone ashore with the initial infantry wave, but those chat did make it to the beach no longer had working radios.4 Historian Stephen E. Ambrose wrote, “The 16th Regiment first and second waves D Day was more reminiscent of an infantry charge across no-man’s land at the Somme in World War I than a typical World War II action.”5 Cornelius Ryan, author of The Longest Day, wrote:

They came ashore on Omaha Beach, the slogging, unglamorous men that no one envied. No battle ensigns flew for them, no horns or bugles sounded. But they had history on their side. They came from regiments that had bivouacked at places like Valley Forge, Stoney Creek, Antietam, that had fought in the Argonne. They had crossed the beaches of North Africa, Sicily and Salerno. Now they had one more beach to cross. They would call this one “Bloody Omaha.”6

A German artillery shell exploded just a few feet from Pinder’s landing craft, shrapnel punching several large holes in the boat’s hull. As the helmsman fought to control the craft, it started to fill with water.7 The ramp dropped to disembark the men, still 100 yards from the beach. They immediately began taking machine gun fire from the enemy gun installations on the cliffs above the shoreline. Confusion reigned as the men broke for the beach. Some were killed outright, others stopped to help the wounded. Much of the vitally important radio equipment remained in the boat as the men scattered in the carnage. In his 1994 article, “0-Day Plus 50 Years,” General Gordon R. Sullivan, then Chief of Staff of the United States Army, wrote:

In a time before transistors and microprocessors, radios capable of reliable shore to-ship communications bulked out at 86 pounds, roughly the weight, size and shape of a modern window air conditioner. Getting one of these beasts ashore under pleasant conditions would challenge an Olympian. Wrestling a radio through the tortured surf of Omaha Beach bordered on the impossible.8

General Sullivan devoted a full page of his story to Pinder.

Pinder shouldered one of the big radio systems and staggered forward out of the tilted, smashed landing craft. Head bowed, deliberately putting one waterlogged leg in front of the other, he pushed through 100 yards of bullet-torn waves. A German bullet clipped him, and he stumbled. But he rose again, a little unsteady, and kept going. He made it to the pile of stones where his soaked partners lay gasping for breath.9

Pinder sustained several wounds. Second Lieutenant Leeward Stockwell said, “Almost immediately on hitting the waist-deep water he was hit by shrapnel. He was hit several times and the worst wound was the left side of his face. Holding the flesh with one hand he carried the set to shore.”10

That trip alone was beyond the power of most people. But Technician 5th Grade Pinder knew that one radio would not be enough in this firestorm. He turned back, heading into the deadly waters. Once again, his comrades marveled as he waded out to the half-sunken landing craft to retrieve a backup radio set and some other items. He managed to get the second load ashore without incident, weaving slowly around rusty obstacles, through geysers and long strings of machine-gun bullets. 11

Pinder’s company commander, Captain Stephen Ralph, said, “He knew the equipment was sorely needed. Three times he made trips into the water and each time drew a deadly hail of fire from the cliffs above. He knew he was critically wounded.”12 Pinder made it back to the landing craft a third time to pick up spare parts and code books.

As he started back, a German machine gunner found the range. Bracketed by water spouts that showed the path of the bullets, Pinder sped up. But his luck ran out. A burst caught him full on and ripped open his side. He fell, somehow got up, and struggled to the beach, and his radios. His fellow communicators rook his burden and turned to help him, but Technician 5th Grade Pinder waved them off. He would be all right. Rather than seek a medic, he looked to his radio sets. Pinder seemed fixated on getting them operational. The radioman was still fiddling with the devices when he passed out from loss of blood. He died later that morning. But his embattled regiment had found its electronic voice. 13

Early life

John Joseph Pinder, Jr., was born on June 6, 1912, in McKees Rock, Pennsylvania, the oldest of John and Laura Pinder’s three children. John Pinder, Sr., worked in the steel mills and the family moved around Pennsylvania, living in McKees Rock 1912- 1925, Vanport and Coraopolis until 1929, and Butler from 1929 until the family moved to Burgettstown in 1939. Two other Pinder children, Martha and Harold, were born in 1915 and 1922. Martha died in 1996. Harold, who still lives in Pittsburgh, provided much of the information for this article.

Joe Pinder graduated from Butler High School in 1931. His high school yearbook, The Senior Magnet, included a western short story, “On the Road to the Bar X,” that Joe wrote. The yearbook referred to Pinder as John and Johnny, but his brother Harold says that everyone called him Joe.

Pinder spent the next several years pitching semi pro baseball in the greater Pittsburgh area. The Depression was in full swing and minor league jobs, like work in general, were scarce.

Joe’s professional debut came late in the 1935 season for his hometown club, the Butler Indians of the Class D Pennsylvania State Association, then the lowest rung of the Cleveland Indians farm chain. Joe was unimpressive in his first game, so nervous that he”couldn’t get his fastball over and his curve swept wide of the plate.”14 Several days later he turned in an excellent mound performance, limiting his opponents to three hits over seven innings. Pinder appeared in eight league games in 1935, turning in a 3-2 won-lost record with 29 walks and 35 strikeouts in 46 innings of work, and Butler reserved his contract for 1936. At least two of Joe’s teammates, Mike McCormick and Oscar Grimes, eventually made their way to the major leagues.

Cleveland dropped their sponsorship of the Butler team over the winter and the New York Yankees be gan what would be a long working relationship with Butler. In 1947, his rookie season in professional ball, Whitey Ford played for the Butler Yankees, then in the Class C Middle Atlantic League.

Joe’s time on the Yankees payroll was short. He appeared in only a few games for Butler in 1936 before being released in late May.

Before the release, Butler played exhibition games with the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Pinder drew a start against the Crawfords, whose batting order included Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell, Judy Johnson, Josh Gibson, and Oscar Charleston. The Crawfords, possibly the greatest Negro League team ever assembled, had little trouble with the Class D club and waltzed their way to an 11- 3 win. Pinder gave up just three hits in his three innings but his teammates booted routine plays and he allowed six runs. Joe retired Gibson both times he faced him, once on a fly to center and then on a routine grounder to the shortstop. Bell was 0-for-1 with a walk, Charleston flied out and singled, and Johnson doubled and walked.

Hard luck

Joe played semipro ball for the remainder of 1936 and all of 1937. He tried out with the Washington Senators’ Class D Sanford Lookouts in the Florida State League in 1938 and made the team. The Lookouts finished last with a 53-87 record, 34-1/2 games out of first place. Pinder turned in nine wins and 18 losses, completing 16 of his 29 starts. His ERA was 4.04 and his strikeout to walk ratio was dead even, 155 passes and 156 strikeouts in 234 innings pitched. On June 23, 1938, the Sanford Herald wrote:

The hardest luck pitcher in the Florida State League or any other league is none other than Joseph Pinder, youth from Butler, Penn., who has lost 12 games this season and won only two. Pinder has gained a considerable amount of control and has picked up on his pitching in general during the last month or so regardless of the fact he has lost the last 10 games in a row. Each time Pinder walks on the hill his mates make up their minds to win one, and they have come so close that it would be impossible for anything else to happen other than someone dropping dead. Pinder hurled 15 innings against DeLand and lost. Tuesday night he hurled a beautiful game and lost 3 to 2. In Gainesville the other evening he held them scoreless and in the fifth inning had to retire due to a sudden ailment in his right arm. So Pinder is still working hard and one of these days we are going to see him walk off the mound with that victory under his belt.

Pinder’s luck, and his pitching, improved dramatically after that point in the season. He tossed one-hitters versus St. Augustine on June 30 and the DeLand Reds on July 29. Wildness continued to be his main problem. He beat DeLand on August 10, 11- 1, allowing five hits but passing eleven batters. On July 9, 1938, this article appeared in the Sanford Herald:

One of the most promising rookies on the Lookouts squad this season is John Joseph Pinder, ace right-handed pitcher who nearly entered the hall of fame last week when he hurled a one-hitter against the St. Augustine Saints…

Pinder was the workhorse of the Lookouts hurling corps earlier in the season, starting games and also doing a bit of relief work. At the present, however, Joe has become a regular starter and gets his four days rest between hurling duties.

Pinder has a lot of stuff and his curveball is dreaded by the other clubs in the league. His fast ball comes in very handy after he slips a curve ball by and it hops and travels with more speed than one of an average hurler. The youngster has the stamina and courage to make a big leaguer some day and he takes his work very seriously.

Pinder was retained by Sanford for 1939. Former American League batting champion Dale Alexander came down from the Chattanooga Lookouts to manage Sanford, and the team responded to his leadership by copping the league pennant with a 98-35 record. The team’s strength was its pitching staff which consisted of Sid Hudson (24-4), Cleo Jeter (22-9), J. Harry Dean (21-4), and Pinder {17-7). Hudson won the league’s triple crown of pitching, leading in strikeouts (192) and ERA (1.79) as well as wins, and when the season was over the Washington Senators purchased the contracts of both Hudson and Dean. Pinder tossed 211 innings in 35 games. His ERA was 3.94 and he again walked as many batters (115) as he fanned (117). Hudson was Pinder’s teammate in 1938 and 1939. He compiled a major league won-lost record of 104-152 over twelve seasons, then became a successful big league pitching coach. Today, at age 85, he resides in Waco, Texas. On Veterans Day, November 11, 2000, Hudson wrote to the author:

In 1938 Joe Pinder and l were roommates in spring training at Sanford, Florida-at the hotel there.

We got to know each other quite well, but, of course, most of our talk was about baseball trying to learn different pitches from each other.

He was a very nice fellow, and a real gentleman.

We had a four-man starting pitcher staff and he was one of them. We four pitchers won 84 games that year-winning the pennant.

As well as I remember, he had a good curveball, and change, and an average fast ball. I suppose his only problem was his control, at times.

I certainly feel honored to have been associated with him in baseball.

One other member of the 1939 Sanford club, Hillis Layne, went on to the majors. Layne compiled a minor league batting average of .335 over a career that ran 1938-1958, and he won the 1947 Pacific Coast League batting crown. His major league career consisted of 107 games, all with Washington, in the 1940s. While Hudson knew that Pinder had been killed in the war, Layne didn’t. On July 30, 2000, he wrote to the author:

Thanks for your letter as it brings back memories of perhaps my most enjoyable year in baseball. As one who played Class D-C-B AA-AAA and the major leagues, the Sanford team of 1939 could hold its own with many of the teams I played with. This club was called the best Class D club that was ever assembled. The club had five pitchers with outstanding ability and all could pitch with any club to day. Hudson, Pinder, Jeter, Dean and Al Nixon.

l especially remember Joe Pinder, a stocky built right hander. A real competitor with a live fast ball and good curve. As a teammate of Joe’s, l can see why Congress presented him with the Medal of Honor. Aside from being a fine ball player he was a great person and a good friend.

I have wondered what happened to Joe since we played at Sanford and although I am sorry he is gone, it makes me proud of what he did in the service of our great country.

Oddly, Washington had two minor league teams in the Florida State League in 1939, and on July 10, Pinder faced an Orlando Senators lineup that included former University of Michigan football and track star Elmer Gedeon. Gedeon appeared briefly in September that year for Washington and, like Pinder,would be killed in action during the war.15

Pinder began this third year with Sanford in 1940. The team had changed its name from the Lookouts to the Seminoles, and Alexander, Hudson, and Layne had all moved on. Stan Musial played for Daytona Beach in the Florida State League in 1940. Sanford and Daytona Beach met three times in late April and early May but Pinder and Musial never appeared in the same game. On May 14, 1940, the Sanford Herald wrote:

Joe Pinder, for two years one of the mainstays of the Sanford pitching staff, yesterday joined the hurling corps of the Macon Peaches, Manager Whitey Campbell announced as he released the information to the public that he had permitted Joe to leave the Seminole staff to better himself. Campbell said he was sorry to see Pinder go but that if he had an opportunity to rise, he did not want to see him held back.

Macon was in the Class B South Atlantic League, and Joe’s short time there would be his highest level of professional competition. A Brooklyn Dodgers farm team, Macon was managed by former major leaguer Milt Stock. The team’s star player was Stock’s son-in-law, Eddie Stanky.16 Pinder won a game and lose a game for Macon. On June 11, 1940, the Fort Pierce News-Tribune announced that the Fort Pierce Bombers of the Class D Florida East Coast League had secured Joe from Macon. Fort Pierce finished the season in fifth place and Pinder turned in just 4 wins against 12 losses. His earned run average, a nifty 2.91, was indicative of his luck that year. Joe arrived in Fort Pierce the next January, hoping to get a jump on the 1941 baseball season. On February 2, the News Tribune wrote:

Joe Pinder, the stocky, square-set little Pennsylvanian with the blinding fast ball, is back in town and is ready for the Fort Pierce Bombers 1941 baseball season.

This quiet, amiable and almost shy person, who had some of the toughest luck last season besides a disastrous record of four wins and 12 losses, has spent the fall and winter months in Pennsylvania with his parents where he worked like the dickens and hunted plenty. Joe registered for the selective service while there. Being outdoors most of the time and quite frequently on the pivot end of an axe, Jo-Jo is in tip top condition.

Pinder thinks 1941 will be his greatest year in professional ball and believes Fort Pierce will be high up in the league race. His ambition is to become a major league player and without any flowery ado he will tell you that his whole life is based on reaching the top in pro ball…

A little more about Joe: He hails from Burgettstown, Pa. and went to high school there, later attended Pennsylvania State College for one year. Not much of an athlete during his high school days, he stuck to books and don’t think he isn’t smart. However, when 18 years of age, he was clocked at 10 seconds for a 100 yard run-which shows his speed on the local diamond last summer was no flash in the pan.

Joe, despite his bad season, was considered one of the most promising moundsmen Fort Pierce had last summer. The 24-year-old hurler will go places this year if the breaks are 50-50.

Shaving a few years off one’s age is a time-honored tradition in baseball, and at the time this article was written Pinder was 28 years old, not 24. Another biographical sketch on Pinder that appeared later in the season gave his birth year as 1917.17

Pinder won 11 games and lost nine with Fort Pierce in a little more than half a season. At the beginning of July, Joe’s contract was optioned to the Greenville Lions of the Alabama State League, another Class D organization. The Greenville manager, former St. Louis Browns pitcher Ernie Wingard, was fired due to the team’s horrible 17-47 record, and Herb Thomas, a native Floridian who had played with the Boston Braves and the New York Giants, was brought in as Wingard’s replacement. Thomas had managed the Fort Lauderdale team in the Florida East Coast League in 1940 and early 1941 and, being familiar with Pinder’s ability, arranged for his transfer.

The Lions went 28-25 after Thomas took over, and Joe’s 6-2 record in just over a month with the team played a vital part.

Joe Pinder has taken part in seven games, winning four and losing one, since he joined the Lions two weeks ago. Had the locals been able to secure him two weeks earlier, the Lions would almost have been assured a place in the play-offs. As it is they are making a strong, though belated, bid for a first division berth-with only three bona fide hurlers on the squad.18

Pinder made an “iron man” attempt on August 18 and started both games of a doubleheader. He tossed a shutout in the opener and received a no-decision in the second game. Joe’s last professional game came on August 28, 1941.

Joe Pinder mastered the Tallassee Indians here Thursday night with a 6-hit pitching effort, and his teammates backed him with a 12-hit assault on two visiting hurlers, to tally a 7-1 triumph. Except for a much discussed play in the seventh, the little Lion right-hander would probably have scored a shutout. 19

Joe’s final tally in 1941 was 17 wins and 11 losses with a 2.93 earned run average. He struck out 136 batters and walked 125. His contract was still owned by Fort Pierce, but as the team departed for the winter, Joe told the Greenville Advocate than he hoped to secure his release and return to Greenville for the 1942 season. He had no way of knowing it at the time, but his professional baseball career was over. His dream of reaching the major leagues would never be realized.

Battlefield

The following information was taken from the history of the 16th Infantry Regiment Association:

The 16th Infantry’s mission was “To assault Omaha Beach and reduce the beach defenses in its zone of action, and proceed with all possible speed to the D-Day Phase Line, and seize and secure it two hours before dark on D-Day.”… The assault began in the early hours of 6 June 1944 as the 16th Infantry Regiment moved toward the shore of Normandy. 600 yards offshore, the LCVP’s encountered intense antitank and small arms fire, but continued to move forward without hesitation. As the first elements hit the beaches, it was apparent that many of the enemy’s strong points had not been eliminated by the pre-invasion bombardment. Those men who lived to get ashore immediately dug holes in the sand, but waves washed them out as fast as they were scooped. To make matters worse, weapons became clogged with sand, and the enemy had reinforced with an added Infantry division, thus almost doubling his firepower. The survivors of the first wave built up a hasty firing line along a low pile of shale. As more men arrived, they found the troops pinned down, congested and trapped … Colonel George Taylor, Regimental Commander, jumped to his feet and said, “The only men who remain on this beach are the dead and those who are about to die! Let’s get moving!” The 16th rallied, and soon, by vicious fighting, much of it hand-to-hand, was pushing toward Colleville-Sur-Mer. Early the following day, the 16th Infantry had seized the beach and an initial foothold that made the invasion a success. 20

While baseball chroniclers may be unaware of the importance of Pinder’s actions early on that long-ago June morning, military historians are cognizant of the strategic value of his deeds and sacrifices. The 116th Infantry Regiment, belonging to the 29th Infantry Division but loaned to the 1st Infantry Division for the invasion, landed on the western half of Omaha Beach. Previously untried in combat, the 116th never got a radio working until late in the day and as a result did not receive effective naval fire support. The best the 116th could do at one point was send blinker Light signals. The 16th attacked on the eastern half of the beach, and General Sullivan’s 1994 historical assessment of the situation credits Joe Pinder as being the reason the 16th was able to sidestep the communications problem that haunted the 116th.

Things turned out differently over in the Big Red One’s 16th Infantry regiment, mainly because of the unflagging willpower of one man-Technician Sch Grade John J. Pinder of Pennsylvania. Pinder and the rest of his communications section carried about half of the regimental headquarters’ radio devices in their pitching little landing craft.21

Pinder’s hometown paper, the Butler Eagle, announced his death in July:

Killed in Action.

A former Butler soldier and baseball pitcher, Private First Class J. Joseph Pinder, Jr., of Burgettstown, Pa., has been killed in action in France, it was announced by the War department.

Private Pinder was the son of J. J. Pinder, Sr., and had taken part in three different in vasions at the time of his death.

A veteran infantryman, Pinder received his first action in the invasion of North Africa and lacer took part in the invasion of Italy. When the American army landed on the French coast, Private Pinder was with the first assault waves and June 6 was killed in action.

Well Known Here

Private Pinder was well known in Butler and was a graduate of the Butler Senior high school. He signed with the Yankee team of Bueler as a pitcher and lacer pitched in the Florida Stace League.

Entering the army on January 27, 1942, he received his basic training ac Camp W heeler, Ga., Fort Benning and Indiantown Gap and then left this country for England. He left England in November of 1942 and had been in action since that time.

Private Pinder leaves his father, J. J. Pinder, Sr., of Burgettstown, Pa., a sister, Martha , of California, and a brother, Lieutenant Harold Pinder, who has been reported missing in action after a bombing mission over Germany in January of 1944.22

Harold Pinder was a B-24 pilot stationed in England. He was shoe down on a bombing raid enroute to Frankfurt, Germany, on January 29, 1944. He was in a POW camp when he received a letter from his father informing him of Joe’s death.

The War Department issued a press release on January 3, 1945, co announce that Pinder had been posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. The Sporting News followed suit in its January 11, 1945, issue:

U.S. Honors Ex-Minor Ace Posthumously

One of the nation’s highest awards, the Medal of Honor, has been awarded posthumously to John J. Pinder, TS/G, of Burgettstown, Pa. former minor league pitcher, before he entered the Army, January 8, 1942.

The 32-year-old infantryman scorned terrible wounds in a race against death to establish vital radio communications on a beachhead in France on O-Day, last June 6, the War Department announced.

Torn by shrapnel and machine gun fire, Pinder lived to see radio parts which he had salvaged from the surf, set up to summon air and sea support.

Pinder’s official Medal of Honor citation reads as follows:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty on 6 June 1944, near Colleville-sur-Mer, France. On D Day, Technician 5th Grade Pinder landed on the coast 100 yards off shore under devastating enemy machine-gun and artillery fire which caused severe casualties among the boatload. Carrying a vitally important radio, he struggled towards shore in waist-deep water. Only a few yards from his craft he was hit by enemy fire and was gravely wounded. Technician 5th Grade Pinder never stopped. He made shore and delivered the radio. Refusing to take cover afforded, or to accept medical attention for his wounds, Technician 5th Grade Pinder, though terribly weakened by loss of blood and in fierce pain, on 3 occasions went into the fire-swept surf to salvage communication equipment. He recovered many vital parts and equipment, including another workable radio. On the 3rd trip he was again hit, suffering machine-gun bullet wounds in his legs. Still this valiant soldier would not stop for rest or medical attention. Remaining exposed to heavy enemy fire, growing steadily weaker, he aided in establishing the vital radio communication on the beach. While so engaged his dauntless soldier was hit for a third time and killed. The indomitable courage and personal bravery of Technician 5th Grade Pinder was a magnificent inspiration for the men with whom he served.

Joe Pinder was initially laid to rest in Normandy, but his family had his remains returned home in September, 1947. The Pinder family plot is in the Grandview Cemetery in Florence, Pennsylvania. There is a special stone commemorating his Medal of Honor.

Close to sixty years have passed since Joe’s death. Time marches on, and, although we shouldn’t, we tend to forget the past. Major league stars today make millions of dollars per year, and chat seems an eternity away from the bloody reality of our army storming ashore that June morning trying to free an entire continent.

Ralph Houk won three pennants and two world championships as manager of the New York Yankees. He also won a Silver Star for leading a reconnaissance platoon across France. Houk, like all men who had experienced combat firsthand, knew that war contains a lot more horror than it does glory. In his autobiography he wrote:

Ruined villages, aerial bombardments, strafing, the crackle of snipers’ bullets, corpses, the stink of war-that stuff reads well in magazines and books. lt happened, it was all there, but not in gaudy words. To the individual soldier nothing mattered except to take orders, to execute chem to the best of his ability-and to survive.23

Houk, in answering a letter about Pinder, wrote to the author:

I did not know or play with Joe Pinder, Jr., but we should not forget what so many people went through in World War Two. l also landed at Omaha Beach a few days after the first wave and it was hard to get through chat alive. Baseball should not forget the Joe Pinders of baseball.24

Allan “Bud” Selig, the Commissioner of Baseball, wrote:

He was a very heroic man who represented his country magnificently. He did what so many other baseball players did, at both the major and minor levels, and that is willingly give up their careers to fight for their country. Joe Pinder stands as a great symbol for future generations of baseball players, for his bravery and courage.25

Few men find themselves participants in events that determine world history. Fewer still are at the fulcrum of that event’s failure or success. Pinder was such a man, an ordinary-Joe selected by face for an extraordinary role.

So here’s to you, Joe Pinder, belated as it may be, a collective tip of our baseball caps, for you will always be baseball’s greatest hero.

Notes

1. Stephen Ambrose, D-Day. June 6, 1944. The Climactic Battle of World War II, 1994, p. 346.

2. U.S. Wor Department press release, January 3, 1945.

3. Cornelius Ryan, The Longest Day, 1959, pp. 194-5.

4. Ambrose. p. 346.

5. Ibid, p. 347.

6. Ryan, p. I96.

7. General Gordon R. Sullivan, “D-Day’ Plus 50 Years.” Anny Magazine, June 1994, p. 26.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. U.S. War Department press release, January 3, 1945.

11. Sullivan, p. 26.

12. U.S. War Department press release, January 3, 1945.

13. Sullivan, p. 26.

14. Butler Eagle, August 22, 1935.

15. See Joseph D. Tekulsy, “Elmer Gedeon.” The National Pastime, 1994, p 68-9.

16. The Sporting News, September 10, 1942, r 10.

17. Fort Pierce News-Tribune, June 22, 1941.

18. Greenville Advocate, August 21, 1941.

19. Ibid, September 4. 1941.

20. 16th Infantry Association website, http://16thinfantry-regiment.org/History/WWII/wwii.html.

21. Sullivan, p. 26.

22. Butler Eagle, July. 1944.

23. Ralph Houk and Charles Dexter, Ballplayers Are Human, Too (New York: Putnam’s, 1962), p. 37.

24. Letter from Ralph Houk to author., September 2000.

25. Letter from Allan “Bud” Selig to author, September 18, 2000.