Baseball’s Major Salary Milestones

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

Baseball milestones are as well known to fans as their own birthdays and addresses. True baseball fans know that 714-511-4256 is not a phone number, but Babe Ruth’s home run total, the career wins of Cy Young, and Pete Rose’s hit tally. Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak of 56 games is a sacred number, 2632 will forever be known as the number of consecutive games played by Cal Ripken, and the single season home run record is held either by Barry Bonds (73), Mark McGwire (70), Sammy Sosa (66), Roger Maris (61), or Babe Ruth (60), depending on your view on steroids, cork, and asterisks.

Baseball’s financial milestones, however, are not as well known. Today, multi-year, multi-million dollar contracts are reported regularly and are as easy to research as the traditional batting, pitching, and fielding statistics we have come to know and love. But this has not always been the case. Before 1985, when the Player’s Association began regularly reporting salaries, we have little readily available information. In fact, until a cache of financial documents came to light in recent years, we had no solid information on any of baseball’s financial details. All that has changed, thanks to the discovery of team financial documents for the New York Yankees and Philadelphia Phillies, and the MLB transaction card files. We now have access to thousands of observations of salary information and detailed financial documents covering several seasons for the Yankees and Phillies.

Baseball’s financial milestones, however, are not as well known. Today, multi-year, multi-million dollar contracts are reported regularly and are as easy to research as the traditional batting, pitching, and fielding statistics we have come to know and love. But this has not always been the case. Before 1985, when the Player’s Association began regularly reporting salaries, we have little readily available information. In fact, until a cache of financial documents came to light in recent years, we had no solid information on any of baseball’s financial details. All that has changed, thanks to the discovery of team financial documents for the New York Yankees and Philadelphia Phillies, and the MLB transaction card files. We now have access to thousands of observations of salary information and detailed financial documents covering several seasons for the Yankees and Phillies.

Mining this enormous wealth of data reveals a rich vein of information for the financial historian and baseball fan alike. In this essay, I use the salary data to put together a list of baseball’s greatest financial milestones, and highlight a fraternity—the $10 million salary club, now more populated than the combined membership of the 3,000 hit and 500 home run clubs.

The issue of salary is not necessarily as straightforward as it might seem. The salary earned by a player includes the salary proper, but may also consist of bonus payments. One can consider salary solely as the contracted amount, but this amount is troublesome on older contracts, since player contracts were not guaranteed until players got enough bargaining power to negotiate guarantees. Before the 1970s, contracts were generally not guaranteed, but rather had ten-day clauses, whereby the owners could waive a player, voiding the remainder of the contract, on ten days notice. Thus a player may have signed a contract for a $6,000 salary, but if he was waived halfway through the season, he was paid only $,3000. Should his salary be calculated based on the signing amount, or the actual amount earned? Today all contracts are guaranteed, so whatever salary is contracted will be paid, regardless of whether a team cuts a player.1

Bonus clauses in MLB contracts have historically run the gamut from signing bonuses to performance bonuses and even attendance bonuses. In his 1938 contract, Bob Feller had a bonus clause paying him $1,000 for each win above 20. That sort of specific personal performance bonus is no longer allowed. Players can be rewarded for appearance-related performance (such as innings pitched or games played), and award-based performance (such as All-Star team or votes in the MVP balloting), but not individual achievements. Bonus clauses, by their nature, are not guaranteed income for players, but income that may be earned based on certain conditions. It is usually not until the end of the season that we can determine if the bonus was earned.

Salary and bonus payments are not the only source of income for baseball players. Other income may be earned from postseason play and endorsements. Because the latter is completely independent of the league itself, it is easy to disregard these earnings when discussing salaries. Postseason shares are also ignored in this study because they are not paid by the team. Rather, the shares are paid out of playoff and World Series revenues, which are actually league earnings. For this essay I focused only on contracted salary.

I used two sources to determine salaries. Data through 1985 are from the misnamed “transaction card” files located in the Baseball Hall of Fame. The transaction cards actually are a record of player contracts that were filed with the league offices. Some transaction information was also recorded, such as the date a player was waived or his contract transferred. The Hall of Fame has a substantial, though not complete, set of these cards ranging from 1911 to 1985. There are few cards for National League players before 1947. The source of salary information post-1985 is the annual release of salaries by the MLBPA.

Due to the missing NL players, this salary milestone study is not based on a complete sample. However, given the looming presence of Babe Ruth—the recognized salary king of his playing days in the AL—it is unlikely that I am missing out on many, if any, of the highest salaried players before 1947.

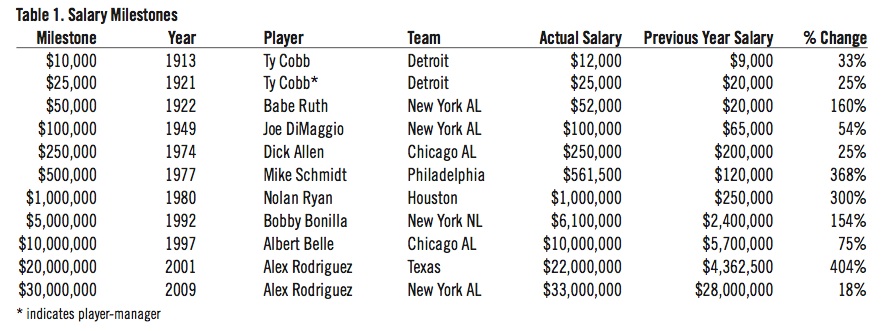

The milestones I have chosen are somewhat arbitrary, but they do paint a picture of the pattern of salary increases over time. As the highest paid salaries have increased, so has the average salary.

(Click image to enlarge)

The first milestone on my list is $10,000, achieved by Ty Cobb in 1913. This is the least certain of the milestones I will discuss, as it was achieved early in the data set, when observations are slimmest. There are reports of player salaries eclipsing $10,000 prior to 1911, but they are not reliable. A couple of examples will suffice to illustrate the state of salary information prior to 1911.

In 1891 and 1892 King Kelly reportedly earned as much as $12,500, or as little as $1,750, depending on which author you read. Unfortunately, none cite a primary document as the source of the number. Similar problems of verifying reported salaries exist for the other examples of players earning five-figure salaries prior to 1913, such as Honus Wagner. According to the Pittsburgh Post Gazette (in a 1931 article), the Flying Dutchman earned $10,000 as early as 1902. In 1985 Business Week reported Wagner earning that salary in 1907, while a Chicago newspaper reported in 1911 that his salary that season was $12,000. Newspaper reports of baseball salaries are notorious for their inaccuracy, and the distance of time does nothing to improve it. I simply did not rely on newspaper, or other unsubstantiated, reports of salaries. While it is possible that there was a player who earned $10,000 prior to Cobb, there is no reliable evidence to support it.

According to information filed with the American League office, Cobb became the first baseball player to earn a five-figure salary when he signed a one year deal paying him $2,000 per month for six months in 1913. The one-year pact was sandwiched in between the three-year, $27,000 contract Cobb had just finished, and a two year $30,000 deal he signed in 1914; 1913 was the last one-year contract Cobb would sign until he became a player-manager in 1921. This in itself was remarkable, since multi-year contracts were extremely rare in the reserve clause era. Cobb’s contract certainly seems well deserved. In 1912 he hit .409, his second consecutive season above the .400 mark, en route to his fifth batting title. The lofty salary did not induce complacency, as Cobb went on to win six of the next seven batting titles.

Eight years later Cobb achieved the next milestone on my list when he signed a one-year contract for $25,000 to become the Tigers player-manager. It was his first of six one-year contracts as player manager. By that time he had won all 11 of his batting titles, amassed nearly 3,000 hits, and sported a career batting average of .370.

The issue of player-managers clouds the salary question somewhat. Since I am interested in player salaries, not manager salaries, I had to make a decision on how to treat player-managers. Ultimately, I decided to count the salary if the player remained a full-time player. Cobb was the only player-manager who made the list.

It took only one more year for the maximum salary to double to $50,000. Babe Ruth earned $52,000 for the Yankees in 1922. Ruth was coming off arguably the greatest single season performance of all time, and had firmly established himself as a superstar. In 1921 Ruth led the league in runs, home runs, RBIs, walks, on-base and slugging averages, and total bases. His 59 home runs transformed the game. It was the third consecutive year in which he had broken the all-time single season home run mark, and his total bested eight other MLB teams. At the turnstile, the Yankees drew more than 1.2 million fans for the second consecutive year, twice what they had drawn in 1919, the year before obtaining Ruth. In 1921 Ruth also overtook the career home run leadership, a spot he would hold until 1974. While Ruth never reached the next milestone on my list, he remained the highest paid player in the game until 1934.

The $100,000 barrier was first achieved by another Yankee in 1949. Joe DiMaggio became the first, and second, player to earn six figures. He received $100,000 again in 1950, but then it would be 13 years before anyone reached that level again. Ted Williams came close, earning $90,000 in 1950 and 1951, but his salary declined thereafter. Williams likely would have reached the $100,000 mark had he not missed the next two seasons while serving in Korea.

When DiMaggio became the first $100,000 player in 1949, he was approaching the end of his career. He was coming off 10 consecutive seasons as an All Star, having finished in the top 10 in MVP voting nine of those 10 years, winning the award three times and finishing second two more times. His career performance, and the fact that the Yankees were drawing two million fans per year, certainly seems to justify his perch as the highest paid player. To put that salary in perspective, DiMaggio was earning thirty times what the average American earned in 1949.

When DiMaggio became the first $100,000 player in 1949, he was approaching the end of his career. He was coming off 10 consecutive seasons as an All Star, having finished in the top 10 in MVP voting nine of those 10 years, winning the award three times and finishing second two more times. His career performance, and the fact that the Yankees were drawing two million fans per year, certainly seems to justify his perch as the highest paid player. To put that salary in perspective, DiMaggio was earning thirty times what the average American earned in 1949.

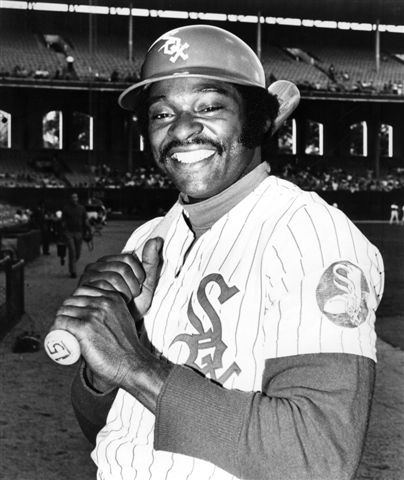

In 1974 Dick Allen became the first non-Hall of Famer to reach one of the milestones when he breached the $250,000 salary mark. Allen received the salary from the White Sox in his final year with the team. He was on the downside of his career by the time he hit this salary milestone. That season he hit 32 home runs, the last time in his career he would top 15. He was coming off a subpar season, one year removed from his 1972 MVP season.

It took only three years for the top salary to double again. In 1977 Mike Schmidt cracked the $500,000 salary level when he took home $561,500. In contrast to Allen, Schmidt was on the upside of his career when he reached this milestone. He was only five seasons and 131 home runs into a Hall-of-Fame career that saw him hit 548 by the time he retired in 1989.

In 1980 Nolan Ryan became the first million dollar player when he signed a four-year free agent contract with the Houston Astros for one million dollars per season. The salary quadrupled what he had been making with the Angels. Ryan is the only pitcher on the milestone list.

There are two other pitchers with notable contracts that bear mentioning here. In 1974 Catfish Hunter kicked off the new era of free agency when he left Oakland and signed a contract with the New York Yankees, which made him the highest paid pitcher in history. In fact, the $239,000 salary briefly made him the highest paid player in baseball. As mentioned, Mike Schmidt topped that salary two years later. In fact, Hunter’s signing was more remarkable for what it didn’t pay him rather than what it did. He reportedly turned down higher offers from both the Kansas City Royals and the San Diego Padres to play for the Yankees. His Yankee contract was far from a record, however. Both Hank Aaron the previous year and Dick Allen in 1974 had earned more than Hunter’s salary with the Yankees.

In 1999 Kevin Brown signed a record $108 million, seven-year deal with the Dodgers. The contract paid him $10 million in 1999 and $15 million per year for the remainder of the deal. It was larded with bonus conditions (signing bonus, MVP bonuses for league, playoffs, and World Series, a bonus for finishing in the top five in Cy Young voting, being selected to the All Star game, winning a Gold Glove or a Silver Slugger award) and perks (eight premium season tickets, 12 round trips on a private jet, and a suite on all road trips) that quickly made news and put Brown at the center of discussions of overpaid, pampered athletes. The $15,000,000 salary he earned in 2000 briefly made him the highest paid player in history, overtaking the previous record held by Gary Sheffield in 1998 when he earned $14.9 million. The focus on Brown’s contract faded the following year with news of the incredible deal that Alex Rodriguez signed with the Texas Rangers. More on that in a moment.

In 1992 Bobby Bonilla earned the first five million dollar annual salary. Bonilla was a free agent when he signed a five-year contract with the Mets, more than doubling his 1991 salary with the Pirates. Bonilla’s record-setting salary was based on four consecutive All-Star seasons and back-to-back Silver Slugger awards. His contract was the highest in MLB history by a whopping 60 percent over the $3.8 million dollar deal signed the year before by former Met Daryl Strawberry, when he left for the Dodgers during free agency. Bonilla’s contract would not be topped for three years, when Cecil Fielder signed a near-milestone deal with the Detroit Tigers for $9.3 million in 1995. Two years later Albert Belle became the first player to earn $10 million dollars in a single season.

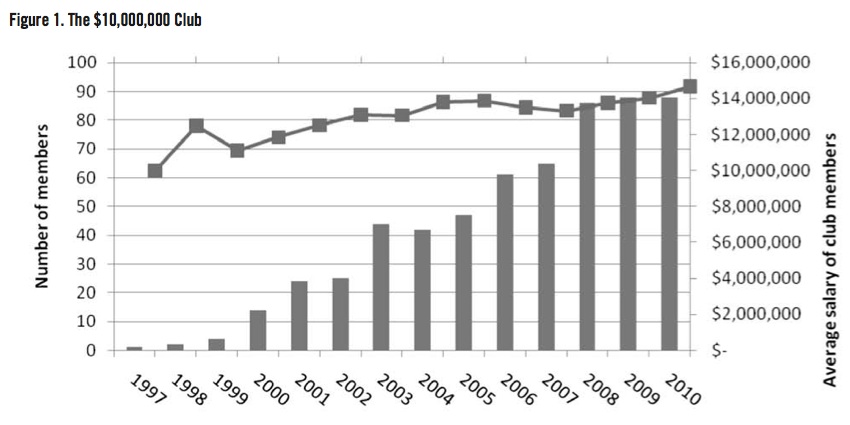

(Click image to enlarge)

In 1997 Belle would be selected to his fifth consecutive All-Star Game, and for the second time the White Sox signed a player to a milestone contract. Belle signed as a free agent, bolting the Indians for a 75 percent pay boost. Belle did not pay immediate dividends for the Sox, slumping from 48 home runs, 148 RBIs, and a .311 average to 30–116–.274, a good season, but a definite drop from 1996 and his 50 home run performance in 1995. Belle bounced back to 49–152–.328, but not enough to interest the Sox, who let him go to the Orioles for two years of escalating wages: $11 million and change in 1999 and $12 million plus in 2000. For their $23 million the O’s saw Belle’s power numbers drop two consecutive years, falling from his 49 homers with the Sox to 37 and then 23, while his average dipped to .297 and then .281 in the final year of his tempestuous career.

Alex Rodriguez is the final member of the milestone club, becoming the first player to hit both the $20 and $30 million dollar levels, in 2001 and 2009 respectively. The Texas Rangers signed A-Rod to the (in)famous 10-year $254 million contract in 2001. While his salary that year was $21,000,000 plus a one million dollar signing bonus, he deferred $5,000,000 of his salary. To tide him through until his deferred salary was paid, Rodriguez earned bonuses that year for finishing sixth in MVP voting ($50,000), being named to the MLB and Baseball America All Star teams ($100,000 each), and for winning the Silver Slugger award ($110,000).

After controversially opting out of his contract during the 2007 World Series, Rodriguez eventually signed a new 10-year, $275 million deal, which led to his earning $33 million in 2009. At 33 (in 2009) Rodriguez was certainly on the downside of his career, but his potential for breaking the all-time home run record should keep the crowds coming and the interest high enough to warrant the contract. Potential sales of A-Rod jerseys and bobbleheads, should he break the record, might be enough to pay off the contract.

Albert Belle became the first member of what is no longer an exclusive club. Since he first earned $10 million, that salary level has been reached at a steadily increasing rate. In 2010 there were 88 players, just under 12 percent of the league, earning in excess of 10 million dollars per season. The average salary of those players has increased only slowly. Since the number of players in the club first reached double figures (14 in 2000) the average salary of the $10 million members has risen by less than 25 percent, from $11.8 million to $14.7 million.

So when will the $50 million barrier be broken? A clue might be gleaned from looking at the source of past salary growth. The salary milestones discussed in this essay are affected by three primary factors: inflation, free agency, and television. Of course nominal salaries will increase just because of inflation. But the growth of the game, particularly television revenues and free agency, made the biggest difference. Thus, new revenue sources are likely to be the driver for ever higher player salaries. New technologies such as the Internet, smart phones, and social networking, as well as further globalization of the MLB brand, provide tantalizing possibilities for MLB to enhance its revenue streams and further propel player salaries into the stratosphere. The $50 million a year player is probably not as far off as we might think, but only time will tell.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. He is fortunate to be able to combine his work with his love of baseball. He is unfortunate to be a lifelong Cubs fan.

Notes

1 Paragraph 7(e) of the standard player contract specifically states that if the club terminates the contract it shall be obligated to continue to pay the player the balance of the salary set forth in the contract. This is backed up by the collective bargaining agreement, which specifically mentions termination conditions. If the club terminates a player contract the termination pay due a player is equal to the unpaid balance of the contracted salary. In short, this means that all contracts are now guaranteed, whether or not the team cuts the player.