Bears, Cubs, and a Moose, Oh My

This article was written by Joseph Wancho

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

The telegram was brash and a bit disrespectful. Simply stated, it read “DEAR MOOSE: TOLD YOU SO. JOE PEP”. 1

The New York Yankees needed pitching help—specifically a boost to their rotation—following the 1962 season. They set their sights on Stan Williams, a right-handed twirler for the Los Angeles Dodgers who had won 14, 15, and 14 games the previous three seasons. “You have to give up something to get something,” runs the old adage, and the Yankees shipped their veteran first baseman, Bill Skowron, to Los Angeles for Williams on November 26, 1962.

Skowron had been a formidable force in the Yankee lineup, batting behind Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. But the Yankees were high on their young first baseman, Joe Pepitone, who—although just a bench player in his rookie year of 1962—took every opportunity to tell Skowron how he was going to take the nine–year veteran’s place. Hence the telegram.

“There are indications that Joe will hit,” said Yankees manager Ralph Houk. “He already has demonstrated his superior skills in the field. I have noted Williams, his style, his potential, and his spirit. I don’t believe we will rue the deal. And I don’t have to remind you that I am a Skowron booster. I certainly hated to see him go. But it just had to be done.” 2

Houk’s words seemed prophetic as Pepitone slugged 27 home runs, drove in 89 runs, and batted .271 in 1963. His numbers were close to the level of those of his predecessor in 1962. Skowron, meanwhile, slumped in Los Angeles, hitting a career-low .202.

As fate would have it, each team won their respective leagues and met in the World Series. Skowron was a veteran of these fall classic matchups, having appeared in seven previous series with New York. It was during these October autumn days that Skowron seemed to really shine. During his post-season career, Moose totaled seven home runs and 26 RBI and batted .283. “I just want to do a little something to help this team,” said Skowron. “Everyone has been great to me. I’ve been awful.” 3

In spite of his subpar regular season, Dodger manager Walter Alston inserted Skowron at first base. Ron Fairly, who manned first base for much of the regular season, played some right field and pinch-hit. The switch worked as Skowron hit .385 with a homer. “Well, it’s October and you always get hot now,” 4 former teammate Bobby Richardson told him during a game. His Dodger teammates celebrated Skowron’s series with a chorus of the familiar Walt Disney refrain: “Mickey Moose, Mickey Moose, M-i-c-k-e-y M-o-o-s-e, Moose, Moose.”

The 1963 series was, in a way, a national coming-out party for Dodgers lefty Sandy Koufax, who led L.A.’s four-game sweep with a 2-0 record and a 1.50 ERA. He struck out 23 Yankee hitters.

Skowron was mighty pleased with the results. “Hell, I wanted to come back and beat the club that traded me,” said Skowron. “I didn’t expect to play in this thing until I read the newspaper lineup. I know I’ve been a donkey. But this tastes awful sweet.” 5

William Joseph Skowron was born December 18, 1930, in Chicago, Illinois. He was one of three children (including brother Edward and sister Jean) born to William and Helen Skowron. The Skowron clan lived in the northwest part of the city. “You’d have to say that we lived in a poor section,” recalls Skowron. “We didn’t have much of anything when I was a kid. My father worked for the Sanitation Department and my mother had to work too.” 6 Helen Skowron was employed at Zenith Radio.

William Sr. played on a semi-pro baseball team, the Cragin Merchants. Young Bill played on the Cragin Juniors. His father’s teammates thought that Bill’s crew cut (given by his grandfather) made him look like Benito Mussolini, the Prime Minister of Italy. He was soon given the nickname Mussolini, later shortened to “Moose.”

He earned a scholarship to Weber High School, an all-boys Catholic school named for Archbishop Joseph Weber. For a short time Bill entertained the idea of becoming a priest. “As a kid I served Mass a lot and I liked to help out at the church,” says Skowron. “I got to know the priests real well and I liked them a lot. My mother and grandmother wanted me to be a priest and I thought it might be a good idea.” 7

Bill Skowron was an excellent all-around athlete, excelling in football and basketball (Weber did not offer baseball as an extracurricular activity). Even as a child, Skowron had a burly build, and he gained 80 pounds in high school. He soon realized his talent as a player and the thought of entering the priesthood faded.

After graduation, he accepted a scholarship to Purdue University. Although he had played baseball in recreation leagues around Chicago, only in college did he begin to play regularly. His freshman baseball and football coach was the legendary Hall of Fame football coach Hank Stram. Skowron made varsity in football, basketball, and baseball his sophomore year. He was a blocking back and punter for the Boilermakers’ gridiron team.

In 1950, Joe McDermott, a scout for the New York Yankees, spotted Skowron playing semi-pro ball in southern Minnesota. McDermott invited Skowron to a workout at Comiskey Park the next time the Yanks were in town.

Skowron showed off his strength at Comiskey. “I took five cuts and put a couple into the second deck. I guess maybe that’s why they signed me.” 8 New York manager Casey Stengel was impressed with the young man and told Moose that if he signed with the Yankees, Stengel would have him in the big leagues in three years. Four days before he was to report to Purdue for football practice, Skowron’s father accepted the Yankees’ offer of a $22,000 bonus. (Moose, as a minor, needed his parents’ assent.)

Purdue football coach Stu Holcomb—later an executive for the Chicago White Sox—accused the Yankees of “thievery” as Skowron headed to winter league baseball in Puerto Rico, rather than return to West Lafayette. Although he had a bright future in major league baseball, Skowron later said he always regretted not getting his degree.

Skowron had been a third baseman as an amateur, but after 21 games at Binghamton of the single-A Eastern League in 1951, Moose was demoted to Class B Norfolk of the Piedmont League to learn the outfield. He certainly aced the hitting part of the job—batting a league-best .334 with 18 homers and 76 RBIs to capture MVP honors—but his manager, Mayo Smith, was worried that Bill’s reactions in left field were too slow and that he had a weak arm.

Despite these concerns, Skowron was promoted for 1952 to the Yankees’ top farm team, the triple-A Kansas City Blues. Skowron showed that his first pro season was no fluke, as he hit .341 for Kansas City and led the American Association with 31 home runs and 134 RBIs. That fall, the Sporting News named him Minor League Player of the Year.

When Skowron reported to camp the next season, Stengel decided the youngster’s ideal position was first base. He sent Moose back to Kansas City to work on his fielding with onetime big-league first baseman Johnny Neun, who especially focused on teaching Skowron proper footwork. “Ground balls didn’t give me much trouble, because of my experience at third,” said Skowron. “But I had trouble shifting my feet and also with foul flies. Johnny spent hours showing me how to move around and after a while, I began to feel at home at first base. Then they drilled me on pops. By the end of the season, I felt better playing first than third.” 9

Skowron also took dancing lessons at Arthur Murray Studio to improve his footwork. Casey’s three-year promise to Skowron was on the verge of becoming a reality. Skowron at last made the big leagues in 1954, starting 56 games at first base. Stengel often used a platoon system to maximize his players’ talents, and first base was no exception. Left-handed hitters Joe Collins and Eddie Robinson were used against right-handed pitchers, with Collins getting most of the starts. Still, the right-handed hitting Skowron showed plenty of moxie, hitting .340 and driving in 41 runs.

The 1954 season was certainly an anomaly for Skowron and his teammates as the Yankees failed to win the pennant. They were back on top the following four seasons, though. Each World Series in that span went the distance as New York split with both Brooklyn and Milwaukee.

After falling to Milwaukee in the 1957 fall classic, the Yankees trailed the Braves the following year three games to one but fought off elimination to win. Skowron played a key role in both the sixth and seventh games, played at County Stadium.

In Game Six, the score was tied at two at the end of nine innings. In the top of the tenth, Gil McDougald homered to give the Yankees the lead. With two outs, consecutive singles by Elston Howard, Yogi Berra, and Skowron pushed the lead to 4 – 2. As it turned out, Skowron’s single to scored Howard was key; the Braves scored one run in their half of the tenth inning before succumbing.

In Game Seven, with the scored knotted 2 – 2, the Yankees scored four runs in the top of the eighth to put the game out of reach. The big blast was Skowron’s three-run homer off Lew Burdette. “It was a lousy pitch that I gave Bill Skowron,” said Burdette. “It was a slider—the same thing he had looked bad on before—but this one I got in too high.” 10

The 5’11’’ Skowron had already become legendary for his physique. “His muscles had muscles,” a familiar saying, was often applied to Moose. It seemed, though, that those muscles were susceptible to tearing. He missed a lot of playing time due to injuries, never playing in more than 134 games through his first five campaigns. “He seems to like the clang of the ambulance,” quipped Stengel. 11

Moose did have a flair for the dramatic. On April 22, 1959, his solo home run in the top of the fourteenth inning delivered a 1 – 0 victory over the Senators at Griffith Stadium. At the time, it was believed to be the longest 1 – 0 game in major league history. Whitey Ford pitched all fourteen frames for the win, striking out 15 Nats.

That July 25 in Detroit, Skowron entered the game in the ninth inning as a pinch-hitter. He remained in the game at first base but while reaching for a throw from third baseman Hector Lopez, Skowron collided with Coot Veal of the Tigers. The result was a fractured wrist and an end to his season. That fall, the White Sox and their go-go style of baseball put an end to the Yankees’ four-year pennant streak.

“When I reported to the Mayo Clinic for a recent check-up,” said Skowron, “the doctors explained to me that I was susceptible to injury because my muscles lacked elasticity. They won’t stretch as they do with the average athlete and that is why I’ve been suffering repeatedly from muscle tears in my legs and back. They recommended swimming as a means towards loosening my muscles and making them more pliable.” 12 The strategy seemed to work, as Skowron averaged 25 home runs, 85 RBIs, and a .282 average from 1960 – 1962. He played in 140 or more games each season during this period.

Skowron hit .375 in the 1960 World Series against Pittsburgh with two home runs and six RBIs. One of those homers was in the fifth inning of the deciding Game Seven at Forbes Field, a classic game won the Pirates on Bill Mazeroski’s home run. The Sporting News named Skowron first baseman on its Major League All Star Team in 1960.

Behind Maris’ and Mantle’s pursuits of Babe Ruth’s home run record in 1961, the Yankees cruised to the pennant. The three M’s (Mantle, Maris, and Moose) set a record for home runs by a threesome in a season (143). The Yankees bested Cincinnati in the World Series in five games, with Skowron adding a homer and five RBIs. They made it two straight world championships in 1962 after a hard-fought seven game series with San Francisco.

After yet another World Series win with the Dodgers in 1963, Moose thought he had a fair shot at staying out west. But the front office felt otherwise, selling him to the Washington Senators for a reported $25,000. Skowron was happy to be back in the junior circuit. “You can count on me to play good ball for you,” Moose promised the front office. “Throw out what happened to me last season. The National League pitching was too new to me.” 13

Skowron may have been on to something. He was batting .271 with 13 homers (three in one doubleheader against Boston on May 10) and 41 RBIs when Washington traded him, with pitcher Carl Bouldin, to the White Sox for outfielder Joe Cunningham and pitcher Frank Kreutzer on July 13, 1964. Chicago was in the midst of a pennant race and manager Al Lopez compared the acquisition of Skowron to that of Ted Kluszewski in 1959. “Skowron should give us a big lift,” said the Sox skipper. “I remember in 1959 when we got Ted Kluszewski from the Pirates. It picked the whole club up and we won a pennant.” 14

Bill Skowron was coming home and he enjoyed hitting at Comiskey Park. Although Moose did not supply the power that Lopez may have been counting on, he still drove in 38 runs and hit .283 in 70 starts at first base. On September 15, Chicago trailed Baltimore by one game and was a half-game up on New York. The White Sox closed the season winning 12 of their final 15 games, including their final nine in a row. But the Yankees were even better, winning 15 of 19 in the same period (the Yankees had four doubleheaders) to nip the Sox by a single game.

Skowron was leading the team in homers (11) and RBIs (39) when he was named to represent the White Sox in the 1965 All-Star Game. Moose was no stranger to the midsummer classic, having been on the A.L. squad each year from 1957 through 1961. But at age 34, this trip was extra rewarding. “To be named to the All- Star team at this time in my career is what makes it so overwhelming to me,” said Skowron. “You know, I wanted to make it so badly this year that I would have been delighted if I had been picked just as a pinch-hitter.” 15

Chicago General Manager Ed Short was impressed with his veteran first baseman. “You know, many of these players, especially the veterans, would just as soon not make the All-Star Team,” said Short. “They’d rather have the three days off. But here is a guy who has been around a long time and you might expect him to be a bit jaded. But he feels distinctly honored. He has real pride in his profession and pride in his performance. It’s too bad there are not more fellows like him.” 16

In 1966 Skowron split time at first base with young Tommy McCraw, a left-handed batter. It appeared as if Skowron’s career had come full circle, as he was back to being a platoon player. His production was decreasing, and in 1967 he was dealt to the Los Angeles Angels for utility player Cotton Nash. Following the season, Skowron retired from the major leagues. Over a 14-year career, Moose compiled a career batting average of .282, belted 211 home runs and 243 doubles, and knocked in 888 runs. He hit over .300 five times in his career and played for eight pennant-winning teams, five of which won the World Series.

Skowron and his first wife, Virginia, had two sons Greg and Steve. Skowron also had a daughter, Lynette, with his second wife, Lorraine. After retiring from baseball, Skowron worked in many professions, mostly promotional and sales positions. He was a fan favorite at fantasy camps and attended many card shows. From 1999 through 2012, he worked as a community affairs representative for the Chicago White Sox.

Bill “Moose” Skowron passed away on April 27, 2012, in Arlington Heights, Illinois. The cause of his death was congestive heart failure, although he had been fighting lung cancer for a few years.

“When I think of Moose, I remember him and Bob Cerv before games,” says Yankee teammate Johnny Blanchard. “The two of them would face each other. They would lock their hands behind each other’s necks. Then it would begin, the banging of heads. They’d do it for fun, but they wouldn’t stop until there were tears running down from their own eyes. I know Moose and Cerv would have fun doing it, but there’s nothing more horrible than hearing two skulls bang together.” 17

Yankee hurler Bob Turley also remembers a fun, gregarious person. “He is this big kid who always enjoys things. He loves to go to banquets and pick up a couple hundred dollars as a speaker. He talks ninety miles a minute and people instantly like him. He also works for the state of Illinois, teaching bicycle safety in the schools. How can you not love a guy who relishes showing little kids how to ride a bike?” 18

JOSEPH WANCHO lives in Westlake, Ohio and is a lifelong Cleveland Indians fan. He has been a SABR member since 2005 and serves as Chair of the Minor Leagues Research Committee. He edited the BioProject’s book on the 1954 Cleveland Indians, “Pitching to the Pennant” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

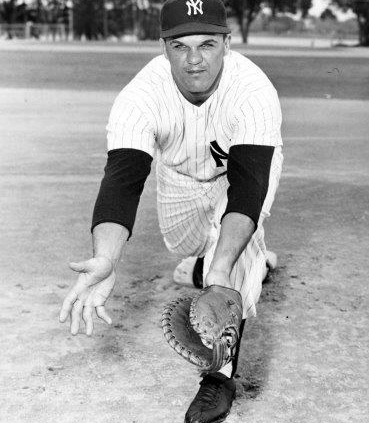

Photo credit

Moose Skowron, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 William J. Ryczek , The Yankees in the Early 1960’s, McFarland and Co, Jefferson, N.C., 2008, p. 5.

2 The Sporting News, March 30, 1963, 30.

3 The Sporting News, October 19, 1963, 3.

4 The Evening Bulletin, October 3, 1963, 44.

5 The Evening Bulletin, October 3, 1963, 44.

6 Players File, Baseball Hall of Fame.

7 Players File, Baseball Hall of Fame.

8 Players File, Baseball Hall of Fame.

9 Players File, Baseball Hall of Fame.

10 New York Times, October 10, 1958, 38.

11 Ryczek, 25.

12 New York Times, January 26, 1960, 38.

13 The Sporting News, December 28, 1963, 17.

14 Chicago Daily News, July 14, 1964.

15 The Sporting News, July 17, 1965, 31.

16 The Sporting News, July 17, 1965, 31.

17 Tony Kubek and Terry Pluto, Sixty-One: The Team, The Record, The Men, MacMillan Publishing, New York, NY, 1987, p. 202.

18 Kubek and Pluto, 202.