Beer and Opulence: The Day the Ballpark in St. Louis had Three Different Names

This article was written by Philip Bolda

This article was published in Sportsman’s Park essays

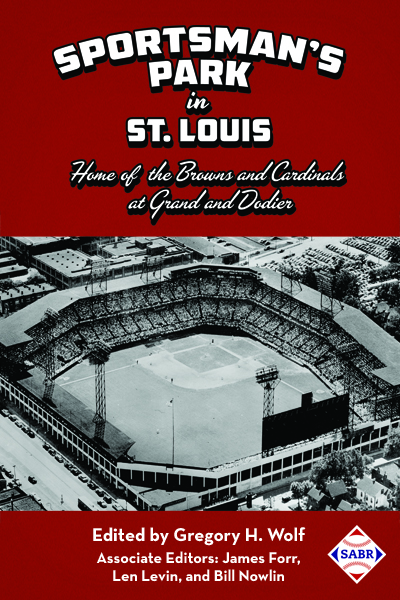

On Friday, April 10, 1953, August Anheuser “Gussie” Busch Jr., head of the firm that purchased the St. Louis Cardinals from Fred Saigh less than two months earlier, announced that the Anheuser-Busch brewery had also purchased Sportsman’s Park for $1.1 million from Bill Veeck, the owner of St. Louis Browns.

On Friday, April 10, 1953, August Anheuser “Gussie” Busch Jr., head of the firm that purchased the St. Louis Cardinals from Fred Saigh less than two months earlier, announced that the Anheuser-Busch brewery had also purchased Sportsman’s Park for $1.1 million from Bill Veeck, the owner of St. Louis Browns.

He said the park would be known as Budweiser Stadium, in honor of the brewery’s chief product. But before the day ended, he revised his announcement – the ballpark would actually be known as Busch Stadium “in memory of the founder and past presidents of Anheuser-Busch Inc. Realizing that Budweiser is a brand name of our product, we decided the name would not be appropriate.”1

What happened that day has long been an object of speculation, and for some, “Budweiser Stadium” has come to represent the moment the “deep pockets” of corporate world would change baseball. Budweiser Stadium is still cited as the tipping point, and comes up in discussions of the public’s distaste for the corporate naming of public stadiums. Gussie Busch was seen as a lout who had never sat through an entire nine-inning game – but through modern practices of corporate marketing and public relations he was later portrayed as a conservator preserving the very best traditions of the game.

Al Fleishman, co-founder of Fleishman-Hillard, a St. Louis public-relations firm, remembered doing a considerable amount of damage control as a participant in the purchase of the Cardinals and Sportsman’s Park. Gussie, Fleishman noted later, had actually signed the papers to purchase the Cardinals without informing the Anheuser-Busch board, or many members of the Busch family.2

Among civic leaders in St. Louis it was said, “Gussie Busch didn’t say good morning unless Al Fleishman told him to. Fleishman became become an important St. Louis civic leader while successfully managing the images of Gussie Busch, the Busch family, and the Cardinals.3

Reaction to Gussie Busch’s initial announcement didn’t stop when he backed away from the new name. It was a flashpoint for those who opposed corporate ownership, the rapid commercialization of the game, and the fusing of baseball and beer. They cynically noted that Gussie soon introduced Busch Bavarian Beer to once again bring the ballpark and his product together.

And for those who knew the business side of baseball in 1953, it must have been seen as a nearly unforgivable self-inflicted wound. Gussie Busch’s coming to baseball had meant swallowing the idea that, for the first time, a franchise would operate as a subsidiary of large corporation. Gussie Busch was president of the team, not the sole owner. Behind him stood a marketing behemoth that cared only how baseball could better sell beer.

Founded by Gussie’s grandfather Adolphus, Anheuser-Busch was second to Schlitz in 1954 and was not even the dominant beer in Sportsman’s Park. St. Louis-based Falstaff beer sponsored the Browns radio broadcasts and was prominent among scoreboard advertisers; another brewery in the Gateway City, Griesedieck, sponsored the Cardinals. But under Gussie Busch – and with a successful presence in baseball – Anheuser-Busch became the largest brewer in the United States and remained so for the next 50 years.

As the weekend began, the St. Louis Post Dispatch printed a critical editorial complaining about “making a sandwich board of Sportsman’s Park.”4 The Metropolitan Church Federation of St. Louis, already uneasy about brewery ownership of the Cardinals, expressed outrage at naming a ballpark for a brand of beer.5 Those targeting baseball’s antitrust issues included political leaders from cities clamoring for major-league franchises of their own. And much of the public perceived the beer industry as somehow dishonest, crass, or even immoral.

Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick reportedly knew of Gussie Busch’s original announcement half an hour before it was made.6 He made no public comment on that day and it is not known if he ever spoke directly to Busch on the matter, although the press generally gave him the credit for Busch’s quick reversal.

Events in St. Louis baseball had required Frick’s intervention for weeks. He spent considerable time persuading Busch to set up a new corporate entity to govern the franchise that – although owned by the brewery – would act as a buffer from the appearance of direct corporate control.

It had been Frick’s edict that forced Fred Saigh, who faced a prison sentence from federal court for tax evasion, to sell the Cardinals to Busch at a fire-sale price in February 1953. Busch’s deep pockets quieted rumors of a move of the Cardinals to another city, but also pushed the Browns out, making the first franchise shifts in major-league baseball in 50 years inevitable.

A few weeks before selling Sportsman’s Park, Bill Veeck attempted to move the St. Louis Browns to Milwaukee. Frick, pressured by Boston Braves owner Lou Perini, blocked the move. On March 13, 1953, Perini moved his Braves to Milwaukee. Veeck was stranded in Busch Stadium for the 1953 season before selling the Browns to local Baltimore owners, who moved the team and renamed them the Orioles in 1954.

Federal antitrust laws prevented breweries from being their own distributors or owning their own taverns or beer gardens. The end of Prohibition left a flurry of state and local laws regulating the sale and consumption of alcohol. Baseball’s own antitrust issues also loomed large. In the 1940s a number of players had bolted major-league baseball and signed with the Mexican League, including Cardinals pitchers Max Lanier and Fred Martin and infielder Lou Klein. Frick’s predecessor, Happy Chandler, suspended the players when they attempted to return to major-league baseball. Legal actions by those players resulted in head-on challenges to baseball’s reserve clause. Chandler had withdrawn the player suspensions in 1949 when faced with defeat in federal court. But baseball’s legal structure had been shown to be vulnerable.

Busch’s combination of beer and baseball precipitated even more federal attention when the US Senate examined legislation to make the antitrust laws applicable to teams affiliated with the alcoholic beverage industry – namely, the St. Louis Cardinals. The purchase of the Cardinals had particularly raised the ire of Colorado Senator Edwin Johnson. Citing the team’s stadium – now rechristened Busch Stadium – and the Clydesdale-drawn wagon on the playing field, Johnson charged that the franchise was a subsidiary of the brewer, and exclaimed, “Mr. Busch’s lavish and vulgar display of beer wealth and beer opulence in the operation of the Cardinal Ball Club should disturb baseball greatly.”7

Johnson proposed legislation to block the sale of the team to Anheuser-Busch and threatened Gussie Busch with a subpoena from the Senate Judiciary Committee.8 (Senator Johnson convened his subcommittee in April 1954 for hearing on a revised version of the bill, stripping the antitrust exemption from any baseball franchise owned by a corporation. The hearing featured testimony from Cardinals catcher Joe Garagiola regarding player contracts. The bill did not move forward to the Senate.)9

Not coincidentally, Senator Johnson was the president of the Denver Bears of the Western League, and the league’s treasurer. He had been concerned that the rapid expansion of national television broadcasts of major-league games and radio broadcasts through the ad hoc networks set up by the Cardinals would “encroach” upon the minors.10 Johnson had been a speaker at the New York baseball writers’ dinner in February, where he threatened to expose major-league baseball as a “cruel and heartless monopoly.”11 The Sporting News had responded by calling Johnson an “articulate spokesman” for the interests of baseball fans.12

Fleischman suggested that the threats were dropped as the senator’s economic self-interests were clearly known. In a twist of fate, Busch later hired Bob Howsam, Johnson’s son-in-law, as the Cardinals’ general manager.

In the months immediately after gaining control of the Cardinals, Busch seemed to be everywhere in The Sporting News and the baseball press. He sought to calm other owners’ fears of his deep pockets, and dismissed charges that he would simply buy the best players. He attended games, standing in ticket lines to inspect their efficiency. He reintroduced promotions such as Ladies Day. He held a ballyhooed family party at his mansion for Cardinals players, staff, and the writers who covered the team, with special gifts for the many wives and children in attendance.

Gussie used his ornate, custom-built railroad car to travel to the minor-league franchises he owned, including local Anheuser-Busch distributors in the festivities. He hosted New York sportswriters at a well-attended luncheon at Toots Shor’s in New York. Fleishman recalled later that Busch had been horrified by condition of the “decrepit” Sportsman’s Park, saying that would rather the Cardinals played in Forest Park – the site of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.13 Gussie invested an additional $1.5 million of company money in Sportsman’s Park, redesigning it, replacing or repairing every seat, removing the advertising from outfield walls, planting shrubbery in the center-field bleachers, installing new loges, erecting a new scoreboard, and remodeling the dugouts and clubhouses.14

St. Louis fans persisted in calling the facility Sportsman’s Park, a title that had endured at Grand and Dodier since 1881, and with Busch’s attention to the fan experience it would come to be hailed as one of the truly classic ballparks.15

Gussie’s charm and seeming benevolence, along with careful public expenditures of his private wealth and corporate resources, soon had baseball writers referring to him to as “beer’s super-salesman, sportsman and latter-day baseball buff.”16 Veeck would come to represent those who sought to operate major-league franchises without personal wealth or corporate resources, enhancing his image as a hustler, con man, and promoter extraordinaire. 17

PHILLIP BOLDA was born in Milwaukee and grew up within walking distance of Milwaukee County Stadium. A graduate of Ripon College, he spent his career on campuses as a university fundraiser and now lives in Tempe, Arizona. He became a member of SABR in 1979 and has contributed to several book projects. He currently serves as the chair of the Fund Raising and Development Committee.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the following were consulted:

Lisle, Benjamin Dylan. “‘You’ve Got to Have Tangibles to Sell Intangibles’: Ideologies of the Modern American Stadium, 1948-1982,” Dissertation, University of Texas-Austin, May 2010.

McGuire, John M. “Brown Out: Brewery’s Purchase of the Cards Doomed Veeck’s Browns,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, February 21, 1993.

Notes

1 United Press International, “Sadder but Wiser: Name Park Busch Stadium/Frick Rules Out Budweiser,” New York Herald Tribune, April 11, 1953.

2 John M. McGuire, “Versions Differ on the Purchase of the Cards by Anheuser-Busch,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, February 21, 1993.

3 “100 People Who Shaped St. Louis,” St. Louis Magazine, December 27, 2007.

4 “Sadder but Wiser.”

5 McGuire.

6 “Sadder but Wiser.”

7 Christian H. Brill and Howard W. Brill, “Take Me Out to The Hearing: Major League Baseball Players Before Congress,” Albany Government Law Review, Volume 5, Issue 1, 2012.

8 McGuire.

9 Red Smith, “Capitol Capers,” Sarasota Journal, April 12, 1954.

10 McGuire.

11 “Senator Johnson’s Warning on Majors’ Video Policy,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1953.

12 Ibid.

13 McGuire.

14 Al Hirshberg, “Mistakes Helped Lose Braves for Hub, Says Scribe,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1953.

15 Roger Angell, “The Series, Two Strikes on the Image,” New Yorker, October 24, 1964.

16 Gerald Holland, “Gussie Busch’s Kind of Day,” Sports Illustrated, May 20, 1957; “Capitol Capers.”

17 Bill Veeck and Ed Linn, The Hustler’s Handbook (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989).