Before Jackie Robinson: Baseball’s Civil Rights Movement

This article was written by Peter Dreier

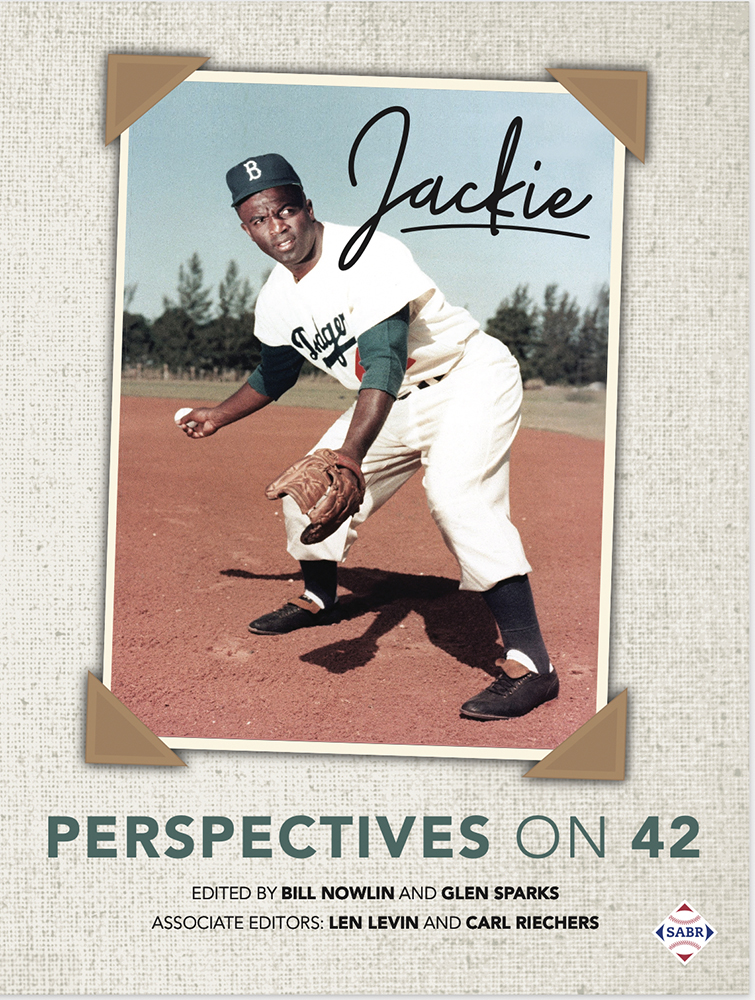

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

In February 1933 – when Jackie Robinson was 14 years old – Heywood Broun, a syndicated columnist at the New York World-Telegram, addressed the annual dinner of the all-White New York Baseball Writers Association. If Black athletes were good enough to represent the United States at the 1932 Olympic Games, Broun said, “it seems a little silly that they cannot participate in a game between the Chicago White Sox and St. Louis Browns.” There was no formal rule prohibiting Blacks from playing in the major leagues, he said, but instead a “tacit agreement” among owners. “Why, in the name of fair play and gate receipts should professional baseball be so exclusive?”1

In February 1933 – when Jackie Robinson was 14 years old – Heywood Broun, a syndicated columnist at the New York World-Telegram, addressed the annual dinner of the all-White New York Baseball Writers Association. If Black athletes were good enough to represent the United States at the 1932 Olympic Games, Broun said, “it seems a little silly that they cannot participate in a game between the Chicago White Sox and St. Louis Browns.” There was no formal rule prohibiting Blacks from playing in the major leagues, he said, but instead a “tacit agreement” among owners. “Why, in the name of fair play and gate receipts should professional baseball be so exclusive?”1

That same month, Jimmy Powers, a popular columnist for the New York Daily News, the nation’s largest-circulation newspaper, interviewed baseball executives and players, asking if they’d object to having Black players on their teams. NL President John Heydler, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, and star players Herb Pennock, Lou Gehrig, and Frankie Frisch, told Powers they didn’t object. Only New York Giants manager John McGraw – who, ironically, had tried to hire a Black player (posing as a Cherokee Indian) when he managed the Baltimore Orioles in 1901 – told Powers he’d opposed the idea. In his February 8, 1933, column, Powers predicted that Blacks would eventually play major-league baseball. “I base this upon the fact that the ball player of today is more liberal than yesterday’s leather-necked, tobacco-chewing sharpshooter from the cross roads.”2

Later that month, Chester Washington, sports editor of the influential Black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier, coordinated a four-month series reporting the views of major-league owners, managers, and players about baseball segregation. It began with an interview with Heydler, who said, “I do not recall one instance where baseball has allowed either race, creed, or color to enter into the question of the selection of its players.”3 The paper quoted Philadelphia Phillies President Gerry Nugent: “Baseball caters to all races and creeds. … It is the national game and is played by all groups. Therefore, I see no objections to negro players in the big leagues.” Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis refused to respond to the Courier, but his assistant Leslie O’Connor said there was no rule against Black players. Hiring decisions were made by owners, not the commissioner, he said.

The saga of how Robinson broke baseball’s color line in 1947 has been told many times in books, newspaper and magazine articles, and Hollywood films. It is typically told as the tale of two trailblazers – Robinson, the combative athlete, and Dodgers President and general manager Branch Rickey, the shrewd strategist – battling baseball’s, and society’s, bigotry.

The Jackie Robinson Story, released in 1950 at the height of the Cold War, five years before the Montgomery bus boycott, celebrated Robinson’s feat as evidence that America was a land of opportunity where anyone could succeed if he had the talent and will. The movie opens with the narrator saying, “This is a story of a boy and his dream. But more than that, it’s a story of an American boy and a dream that is truly American.” Rickey is portrayed as a benevolent do-gooder who, for moral and religious reasons, believes he has a responsibility to break baseball’s color barrier. The 2013 film 42 spun a similar story. It depicts Pittsburgh Courier reporter Wendell Smith as Robinson’s traveling companion and the ghostwriter for his newspaper column during his rookie season, but ignores Smith’s key role as a leader of the long crusade to integrate baseball before Robinson became a household name.

Most books and articles about this saga ignore or downplay the true story of how baseball’s apartheid system was dismantled. Rickey’s plan came to fruition only after more than a decade of protest to desegregate the national pastime. It was a political victory brought about by a progressive movement.

Throughout the Great Depression – from 1929 to 1941 — millions of workers, consumers, students, and farmers engaged in massive protests over economic hardship. This reflected the nation’s mood, a combination of anger and fear. Franklin Roosevelt’s 1932 election as president, with 57 percent of the vote, added an element of hope. For most Americans, New Deal reforms – including Social Security, the minimum wage, workers’ right to unionize, subsidies to troubled farmers, a massive government-funded jobs program, and stronger regulation of banks and other businesses – offered welcome relief to the suffering. In 1936, they re-elected FDR with 61 percent of the vote.

But some viewed FDR’s program as halfway measures that didn’t challenge the problem’s root causes. The collapse of America’s economy radicalized millions of Americans. Because the Depression imposed even greater hardships on Blacks than Whites, Black Americans were more open than most Whites to radical ideas.

At the time, America was deeply segregated. Black Americans, 10 percent of America’s population, were relegated to second-class status and denied basic civil and political rights in the South and elsewhere. The subjugation of Negroes, wrote sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, was “the most glaring conflict in the American conscience and greatest unsolved task for American democracy.”4

In the 1930s and 1940s, civil-rights activists fought against discrimination in housing and jobs, mobilized for a federal anti-lynching law, protested against segregation within the military, marched to open up defense jobs to Blacks during World War II, challenged police brutality and restrictive covenants that barred Blacks from certain neighborhoods, and boycotted stores that refused to hire African-Americans. The movement accelerated after the war, when returning Black veterans expected that America would open up opportunities for Black citizens.

As part of that movement, the Negro press, civil-rights groups, progressive White activists and unions, the Communist Party, and radical politicians waged a sustained campaign to integrate baseball. The coalition included unlikely allies who disagreed about political ideology but found common ground in challenging baseball’s Jim Crow system. They believed that if they could push the nation’s most popular sport to dismantle its color line, they could make inroads in other facets of American society.5

A few White journalists for mainstream papers, including Broun (a socialist) and Powers, joined the crusade. They reminded readers that two Black athletes – Jesse Owens and Mack Robinson (Jackie’s older brother) – had embarrassed Hitler in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin by defeating Germany’s White track stars, and that White and Black Americans alike cheered Joe Louis after he knocked out German Max Schmeling (whom Hitler touted as evidence of White Aryan superiority) in the first round at Yankee Stadium before a crowd of 70,043 in 1938.

With a few exceptions, during the 1930s and 1940s sportswriters for White-owned newspapers ignored the Negro Leagues and the burgeoning protest movement against baseball’s color line. In contrast, readers of the nation’s Black papers were well-informed about these players and the protests. These papers did more than report; they were advocates for civil rights in society and baseball.

Their reporters – especially Smith and Washington of the Pittsburgh Courier, Fay Young of the Chicago Defender, Joe Bostic of the People’s Voice in New York, Sam Lacy and Art Carter of the Baltimore Afro-American, Mabray “Doc” Kountze of Cleveland’s Call and Post, and Dan Burley of New York’s Amsterdam News – took the lead in pushing baseball’s establishment to hire Black players. They were joined by Lester Rodney, sports editor of the Communist Daily Worker. They published open letters to owners, polled White managers and players, brought Black players to unscheduled tryouts at spring-training centers, and kept the issue before the public.

For Smith, the matter was personal. In 1933, as a 19-year-old, he pitched his American Legion club in Detroit to a 1-0 victory in the playoffs. A scout for the Detroit Tigers told him, “I wish I could sign you, too, but I can’t,” because of his race. Those words “broke me up,” Smith recalled. “It was then I made a vow that I would dedicate myself to do something on behalf of the Negro ballplayers. That was one of the reasons I became a sportswriter.”6

Thanks to Smith, the Courier – with the largest circulation of any Black newspaper, growing from 46,000 readers in 1933 to over 250,000 in 1945 – became the leading voice against baseball’s racial divide. Smith expanded the Courier’s efforts to protest segregation in baseball and other sports. In his first column on the issue, on May 14, 1938, Smith criticized Black Americans for spending their hard-earned money on teams that prohibited Black players. “We know they don’t want us, but we keep giving them our money.” He also criticized Black Americans for not patronizing the Negro League teams, putting them in constant financial jeopardy.7 Smith was echoing the civil-rights movement’s demand to boycott businesses that refused to hire or show respect for Black Americans.

In 1939 Smith interviewed National League President Ford Frick, who claimed that major-league teams didn’t employ Black athletes because White fans would not accept them. He also noted that Black players wouldn’t be allowed to travel with their teams during spring training or in certain major-league cities because Southern hotels, restaurants, and trains would not accept them – a reality that, Frick said, would undermine team spirit.

Frick’s comments inspired Smith to interview eight managers and 40 National League players, which he published in a series entitled “What Big Leaguers Think of Negro League Baseball Players” between July and September 1939. Among the managers, only the Giants’ Bill Terry said Blacks should be barred from major-league teams. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher told Smith: “I’ve seen plenty of colored boys who could make the grade in the majors. Hell, I’ve seen a million. I’ve played against SOME colored boys out on the coast who could play in any big league that ever existed.” He added: “I certainly would use a Negro ball player if the bosses said it was all right.”8 Other managers and players agreed with Durocher’s view, expressing hope that Black players would one day play in the majors.9

The Negro papers extolled the talents of Black players as equal to their White counterparts. As evidence, they pointed to the outcomes of exhibition games between Negro teams and White players. On October 20, 1934, for example, the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs beat a team of major leaguers, which included the St. Louis Cardinals’ ace pitcher Dizzy Dean. A week later, Satchel Paige and the Pittsburgh Crawfords defeated the same contingent of major leaguers. In 1938 Dean told the Courier that Paige was “the pitcher with the greatest stuff I ever see.”10 In 1939 Dean – who grew up in rural Arkansas – told Smith that Paige, Josh Gibson, and Oscar Charleston were among the best players he’d ever seen. “I have played against a Negro all-star team that was so good we didn’t think we had a chance,” he said.11

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Communist Party – although never approaching 100,000 members – had a disproportionate influence in progressive and liberal circles. The CP took strong stands for unions and women’s equality and against racism, anti-Semitism, and emerging fascism in Europe. It sent organizers to the South to organize sharecroppers and tenant farmers and was active in campaigns against lynching, police brutality, and Jim Crow laws. The CP led campaigns to stop landlords from evicting tenants and to push for unemployment benefits. In Harlem, it helped launch the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign, urging consumers to boycott stores that refused to hire Black employees.12 Prominent Black Americans, including Paul Robeson, Richard Wright, and Langston Hughes, were attracted to the CP.

In 1938 the American Youth Congress, a group led by CP activists, passed a resolution censuring baseball for excluding Black players. In 1939 New York State Senator Charles Perry, who represented Harlem, introduced a resolution that condemned baseball for discriminating against Black ballplayers. In 1940 sports editors from New York area college newspapers, many of them influenced by radical ideas, adopted a similar resolution. A story in the Daily Worker in 1940 proclaimed: “The campaign for the admission of Negro players to the major leagues has now become a national issue, drawing support from tens of thousands of fans and fair-minded Americans who have the best interest of the game at heart. … There is now the Committee to End Jim Crow in Baseball, which is growing rapidly and which has just launched a campaign to end this evil. … The magnificent talents of the Negro would be a tonic to the game, enriching it beyond measure.”13

Unions played an important part in this crusade. The New York Trade Union Athletic Association, a coalition of progressive unions, organized an “end Jim Crow in baseball” day of protest at the 1940 World’s Fair.14 Unions and civil-rights groups picketed outside Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds, and Ebbets Field in New York, and Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field in Chicago. The speakers included Congressman Vito Marcantonio of New York and Richard Moore of the left-wing National Negro Congress. Over several years, these activists gathered more than a million signatures on petitions, demanding that baseball tear down the color barrier. In 1943 similar pickets occurred outside Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, where the minor-league Angels played.15 Angels President Pants Rowland wanted to give tryouts to several Black players. He and Philip Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, the parent team, met with William Patterson, a civil-rights lawyer and Communist Party member. But Wrigley nixed the tryout idea, saying he favored integration but “I don’t think the time is now.”16

No White journalist played a more central role in baseball’s civil-rights movement than the Daily Worker’s Lester Rodney. Born in 1911, he was radicalized by his family’s own hardships and by the enormous suffering he witnessed during the Depression.

He first encountered the Daily Worker while attending New York University. He agreed with its political perspective but was appalled by its failure to take sports seriously. The paper occasionally wrote about union-sponsored and industrial baseball leagues, but not professional sports. He wrote a letter to the paper’s editor, criticizing its sports coverage. “You guys are focusing on the things that are wrong in sports. And there’s plenty that’s wrong. But you wind up painting a picture of professional athletes being wage slaves with no joy, no elan – and that’s just wrong. Of course there’s exploitation, but … the professional baseball player still swells with joy when his team wins. … (T) hat’s not fake.” The paper hired him and soon made him its first sports editor. He served in the capacity from 1936 to 1958, when he quit the Communist Party.

Durocher once told Rodney: “For a fucking Communist, you sure know your baseball.”17 For a dozen years, Rodney was one of the few White sportswriters to cover the Negro Leagues and to protest baseball segregation. One of his editorials attacked “every rotten Jim Crow excuse offered by the magnates for this flagrant discrimination.”18 “Paige Beats Big Leaguers: Negro Team Wins 3-1 Before 30,000 Fans in Chicago,” declared a 1942 headline, typical of the Daily Worker’s advocacy journalism.19

According to Rodney, the paper “had an influence far in excess of its circulation, partly because a lot of our readership was trade union people” and because it was “on the desk of every other newspaper” in New York.20

In a 1936 interview with Rodney, Frick insisted that there was no prohibition against Black players in the majors and, echoing Landis, said that owners had the responsibility for signing players. Some baseball executives told Rodney that there were no Black players good enough to play in the majors. Others blamed the fans, insisting that they wouldn’t stand for having Black players on their favorite teams. Or they’d blame the players, insisting that they’d rebel if the owners hired Black players to be their teammates.

Like Smith and other sympathetic reporters, Rodney shot down the argument that most players and managers opposed baseball integration. A typical Daily Worker story, from July 19, 1939, was headlined: “Big Leaguers Rip Jim Crow.” It quoted Cincinnati Reds manager Bill McKechnie, who said that “I’d use Negroes if I were given permission.” Reds star pitcher Bucky Walters declared them “some of the best players I’ve ever seen.” Johnny Van der Meer, another pitching ace, said: “I don’t see why they’re banned.” Yankee slugger Joe DiMaggio told Rodney that Satchel Paige was the best pitcher he ever faced.21

Rodney had great rapport with the players. Between 1937 and 1939, he even recruited two progressive players – Yankees third baseman Red Rolfe and Cubs first baseman Ripper Collins – to write for the Daily Worker. They wrote about baseball, not politics, but, according to Irwin Silber, Rodney’s biographer, “the fact that a major-league ballplayer would be willing to write for the Daily Worker signified a degree of legitimacy for the Communist Party – or at least its newspaper – that could hardly have been imagined a few years earlier.”22

According to Rodney, “Readers loved it, of course, but the really fascinating thing was the next day after a story would come out. I’d go into the dressing room before the game – and just picture this – there are the Yankees – the New York Yankees – sitting around the dressing room reading the Daily Worker. If Colonel Ruppert [the Yankees owner] had walked in, he would have had a heart attack.” And there was “not a word of red-baiting” of Rolfe or Collins by their teammates.23

Rodney interviewed Negro players to challenge the myth that they preferred playing in the Negro Leagues to breaking into the majors. In an interview with Rodney, Paige observed: “We’ve been playing a team of major-league all stars after the regular season in California for four years and they haven’t beaten us yet. … Must be a few men who don’t want us to play big league ball. The players are okay and the crowds are with us.”24

For Rodney, reporting and advocacy were intertwined. In 1941 he and sportswriters for Negro newspapers, including Smith, sent telegrams to team owners asking them to give tryouts to Black players. In 1942 the Chicago White Sox reluctantly invited the Negro League pitcher Nate Moreland and UCLA’s All-American football star Jackie Robinson to attend a tryout camp in Pasadena. Manager Jimmy Dykes raved about Robinson: “He’s worth $50,000 of anybody’s money. He stole everything but my infielders’ gloves.” But the two ballplayers never heard from the White Sox again.

In response to Rodney’s telegram, the Pittsburgh Pirates invited Negro League players Roy Campanella, Sammy Hughes, and David Barnhill to a tryout. But as Campanella, later a Hall of Fame catcher with the Dodgers, recalled in his 1959 autobiography It’s Good to Be Alive, the invitation letter from Pirates owner William Benswanger “contained so many buts that I was discouraged even before I finished reading the letter.”25 Benswanger canceled the tryout.

Despite his strong opposition to communism, Smith acknowledged Rodney’s role on behalf of baseball integration. In an August 20, 1939, letter to Rodney in the Daily Worker, Smith wrote that he wanted to “congratulate you and the Daily Worker for the way you have joined with us in the current series concerning Negro Players in the major leagues, as well as all your past great efforts in this aspect.” He expressed the hope of further collaboration.26

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, this coalition escalated its campaign to integrate baseball.

Some African-Americans had mixed feelings about supporting the war effort when they faced such blatant discrimination at home. When he was drafted, Nate Moreland, a Negro League pitcher, complained: “I can play in Mexico, but I have to fight for America, where I can’t play.” Activists carried picket signs at Yankee Stadium, asking, “If we are able to stop bullets, why not balls?”27 An editorial in the New Negro World in May 1942 reflected similar frustrations:

“If my nation cannot outlaw lynching, if the uniform [of the Army] will not bring me the respect of the people that I serve, if the freedom of America will not protect me as a human being when I cry in the wilderness of ingratitude; then I declare before both God and man … TO HELL WITH PEARL HARBOR.”28

A month after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the United States entered the war, James Thompson, a cafeteria worker in Kansas, coined the phrase “Double Victory” in a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier.

“The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in so-called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery and tyranny,” Thompson wrote. “If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict, then let we colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within. For surely those who perpetrate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.”29

Black leaders and newspapers enthusiastically supported the “Double V” campaign. Cumberland “Cum” Posey, owner of the Negro League’s Homestead Grays, suggested, in his weekly Courier column “Posey’s Points,” that every Negro League player wear a Double V symbol on its uniform.

Throughout the war years, Smith, Rodney, and other progressive sportswriters voiced their outrage about the hypocrisy of baseball’s establishment.30

In an open letter to Landis published in the Daily Worker in May 1942, Rodney wrote: “Negro soldiers and sailors are among those beloved heroes of the American people who have already died for the preservation of this country and everything this country stands for – yes, including the great game of baseball. You, the self-proclaimed ‘Czar’ of baseball, are the man responsible for keeping Jim Crow in our National Pastime. You are the one refusing to say the word which would do more to justify baseball’s existence in this year of war than any other single thing.”

In a July 1942 column, Smith wrote that “big league baseball is perpetuating the very things thousands of Americans are overseas fighting to end, namely, racial discrimination and segregation.” The next year, he called on President Roosevelt to adopt a “Fair Employment Practice Policy” for major-league baseball similar to the one he’d adopted in war industries and governmental agencies.

In June 1942, large locals of several major unions – including the United Auto Workers and the National Maritime Union, as well as the New York Industrial Union Council of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) – sent resolutions to Landis demanding an end to baseball segregation. The union leaders told Landis’s secretary, Leslie O’Connor, that unless he let them address the owners’ meeting, they would take the issue to the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), the federal agency created by FDR in 1941 to investigate discrimination in the defense industry and other sectors.31 Landis and the owners refused to meet with them.

The unions’ protest made headlines in both Negro and White newspapers across the country. The stories mostly focused on Landis’s refusal to meet with them, but just getting the issue in the news helped them build public support for their cause.32 The movement gained an important ally when Chicago’s Catholic bishop, Bernard Shiel, announced he would urge Landis to support integration.33 In July 1942, Landis summoned Durocher to a meeting in Chicago, and rebuked him for his comments claiming that baseball banned Black players. Landis issued a statement claiming that “there is no baseball rule – formal, informal, or otherwise – that says a ball player must be white.”34 Most newspapers took Landis at his word, but the Black papers and the Daily Worker called him a hypocrite.

That December, 10 CIO leaders went to the baseball executives’ winter meetings in Chicago to demand that major-league teams recruit Black players, but Landis again refused to meet with them.35 Only Chicago Cubs owner Phil Wrigley broke ranks. After the official meeting ended, he invited union leaders to his office and told them he favored integration and revealed that, contrary to his fellow owners’ claims, there was, in fact, a “gentlemen’s agreement” among them to keep Blacks out of major-league baseball. “There are men in high places,” he told them, “who don’t want to see it.”36 Frustrated by the lack of progress, in February 1943 a broad coalition of unions, left-wing groups, religious and civil-rights organizations, including the Urban League and the NAACP, met in Chicago and adopted a resolution demanding the integration of baseball, to send to Landis, team owners, and President Roosevelt.37

Smith spent much of 1943 lambasting Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith for his outspoken opposition to allowing Blacks in the majors. Griffith insisted that Blacks should focus on improving their own leagues. Smith recognized that Griffith was profiting handsomely by renting his ballpark to Negro League teams. He was also angered that during World War II Griffith signed foreign-born ballplayers, including many Latin Americans, instead of Black athletes to replace White players. Griffith “has so many foreigners on his team it is necessary to have an interpreter,” Smith wrote.38

In December 1943 Smith asked Landis to meet with the publishers of leading Black newspapers at the owners’ December meeting. Landis agreed, pressured in part by a resolution sponsored by a New York City Council member demanding that the major leagues recruit Black players. This was the first time that representatives of the Black community met directly with baseball’s establishment.

Smith brought seven newspapermen along, as well as Paul Robeson, the Black actor, singer, activist, and former All-American athlete at Rutgers. Landis began the meeting by insisting that he wanted it “clearly understood that there is no rule, nor to my knowledge, has there ever been, formal or informal, or any understanding, written or unwritten, subterranean or sub-anything, against the hiring of Negroes in the major leagues.”39

Then Landis introduced Robeson, who gave an impassioned 20-minute appeal, referencing his experience in college and professional football and his current work as an actor, dispelling the idea that desegregation creates chaos. “They said that America never would stand for my playing Othello with a white cast, but it is the triumph of my life,” he declared. “The time has come when you must change your attitude toward Negroes. … Because baseball is a national game, it is up to baseball to see that discrimination does not become an American pattern. And it should do this this year.”40

The owners gave him a rousing applause, but Landis had instructed them to ask him no questions.

Landis next introduced John Sengstacke, president of the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association and the publisher of the Chicago Defender. Sengstacke called the ban against Black players “un-American” and “undemocratic.” Then Ira Lewis, president of the Courier, told the owners it was simply untrue that major-league players would refuse to play against Black athletes, based on Smith’s many interviews. He also noted that Black players could compete with White players at the same level, reminding the owners that Black teams had defeated teams of major leaguers in various exhibition games.41

None of the baseball owners and executives asked the Black publishers any questions. After the meeting ended, they issued an official statement repeating Landis’s claims.

In 1944 Smith wrote several sympathetic stories to help publicize the court-martial of a Black soldier at Fort Hood, Texas – a former UCLA four-sport athlete – for refusing to go to the back of a military bus. The soldier was Jackie Robinson, who befriended Smith and was grateful for his support.

In early 1945, a few months after Landis died, baseball’s owners selected Albert “Happy” Chandler as the next baseball commissioner. As governor and then senator from Kentucky, Chandler echoed the segregationist views of most White Kentuckians. So when Pittsburgh Courier reporter Ric Roberts asked Chandler about allowing Blacks in the big leagues, he was surprised to hear Chandler say that he didn’t think it was fair to perpetuate the ban and that teams should hire players to win ballgames “whatever their origin or race.”42 Baseball’s integration crusaders felt that even if Chandler wasn’t an ally, he wouldn’t be an implacable obstacle as Landis had been.

On April 6, 1945, as the war was winding down, Black sportswriter Joe Bostic of the People’s Voice appeared unannounced at the Dodgers’ Bear Mountain, New York, training camp with Negro League stars Terris McDuffie and Dave Thomas and pressured Rickey into giving them tryouts. The next day, Rickey and manager Durocher watched the two athletes perform, but determined that they were not major-league caliber. Moreover, Rickey was furious. He wanted to bring Black players into major-league baseball, but he wanted to do it on his terms and his timetable. He didn’t want the public to think that he was being pressured into it. “I am more for your cause than anybody else you know,” he told Bostic, “but you are making a mistake using force. You are defeating your own aims.” But the ploy made the news. The New York Times ran a story headlined: “Two Negroes Are Tried Out by Dodgers but They Fail to Impress President Rickey.”43

With many progressive unions and civil-rights groups, a large Black population, and three major-league teams, New York City was the center of the movement to end Jim Crow in baseball. On Opening Day of 1944, for example, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized a demonstration outside Yankee Stadium to enlighten fans and castigate the owners of the game’s most powerful franchise. Several New York politicians were allies of the campaign to integrate baseball. Running for re-election as a Communist to the New York City Council in 1945, Ben Davis – an African-American who starred on the football field for Amherst College before earning a law degree at Harvard – distributed a leaflet with the photos of two Blacks, a dead soldier and a baseball player. “Good enough to die for his country,” it said, “but not good enough for organized baseball.”44

In March of 1945, the New York State Legislature passed, and Republican Gov. Thomas E. Dewey signed, the Quinn-Ives Act, which banned discrimination in hiring, and soon formed a committee to investigate discriminatory hiring practices, including one that focused on baseball.

In short order, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia established a Committee on Baseball to push the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers to sign Black players. Rickey met with LaGuardia but didn’t reveal his plan. Left-wing Congressman Vito Marcantonio, who represented Harlem, called for the US Commerce Department to investigate baseball’s racist practices.

The baseball establishment was feeling the heat. Sam Lacy, a reporter for the Afro-American, wrote to all of the owners suggesting that they set up an integration committee. To deflect the problem and avoid bad publicity, the owners reluctantly agreed to study the issue of discrimination. Rickey (representing the NL) agreed to serve on the committee along with Yankees President Larry MacPhail (representing the AL), Lacy, and Philadelphia Judge Joseph H. Rainey, an African-American. But, according to Lacy, “MacPhail always found a way to be too busy for us,” and the full committee never met. Rickey told Lacy that he would work to integrate baseball on his own.45

Rickey wasn’t pleased with this pressure, which he knew was partly orchestrated by Communists and other radicals.

Rickey’s White scouts, unfamiliar with the Negro Leagues, couldn’t help him find the Black player he wanted to be baseball’s trailblazer. Instead, Rickey had subscriptions to the major Negro newspapers, which published Negro League box scores, statistics, and schedules, and whose sportswriters gave accounts of its best players. In 1945 Rickey gave his scouts a list of players to follow, pretending that he was interested in starting his own all-Black baseball league to compete with the existing Negro Leagues.

Rickey’s search for the right player was inadvertently aided by Isadore Muchnick, a progressive Jewish member of the Boston City Council. In 1945 Muchnick was determined to push the Boston Red Sox to hire Black players. But owner Tom Yawkey was among baseball’s strongest opponents of integration. Muchnick threatened to deny the Red Sox a permit needed to play on Sundays unless the team considered hiring Black players. Working with Smith and White sportswriter Dave Egan of the Boston Record, Muchnick persuaded reluctant general manager Eddie Collins to give three Negro League players – Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams – a tryout at Fenway Park on April 16.

Robinson had already endured the earlier bogus tryout with the White Sox four years earlier in Pasadena. He was skeptical about the Red Sox’ motives now, He and the other two players performed well. Robinson, the most impressive of the three, hit line drives to all fields. “Bang, bang, bang; he rattled it,” Muchnick recalled. “Jackie hit balls over the fence and against the wall,” echoed Jethroe. “What a ballplayer,” said Hugh Duffy, the Red Sox’ chief scout and onetime outstanding hitter. “Too bad he’s the wrong color.”46

The Red Sox, Pirates, and White Sox had no intention of signing any of the Black players from the tryouts. But the public pressure and media publicity helped raise awareness and furthered the cause. And it helped give Rickey, who did want to hire Black players, a sense of urgency that if he wanted to be baseball’s racial pioneer, he needed to act quickly.

After the phony Fenway Park tryout, Smith headed to Brooklyn to tell Rickey about Robinson’s superlative performance. Smith was convinced that among major-league owners, Rickey was the desegregation campaign’s strongest ally. The meeting cemented the relationship between the two men. Smith kept offering Rickey the names of Black ballplayers, but gave Robinson his strongest endorsement.

If Bill Veeck – who voted several times for Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party candidate for president – had his way, major-league baseball would have integrated five years before Robinson signed with the Dodgers. In 1942, when he owned the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers, the 28-year old Veeck learned that the Philadelphia Phillies were bankrupt and for sale. He quietly found investors, including CIO unions, then made a deal with the Phillies’ owner, Gerry Nugent, to buy the team.47 As he left for Philadelphia to seal the deal, he ran into John Carmichael, a Chicago Daily News sports columnist. He told Carmichael, “I’m going to Philadelphia. I’m going to buy the Phillies. And do you know what I’m going to do? I’m going to put a whole Black team on the field.”48

Veeck believed that recruiting Negro Leagues stars could turn the lowly Phillies into a winning team and demonstrate that Black players were of major-league caliber. But hours before leaving for Philadelphia, Veeck made the mistake of informing Landis about his intentions. Veeck later recounted: “I got on the train feeling I had not only a Major League ball club but I was almost a virtual cinch to win the pennant next year.” Before he had even reached Nugent’s office the next day, Veeck learned that the NL had taken over the Phillies the night before and was seeking a new owner. Veeck was not on their list. As Veeck recounted in his 1962 autobiography, Landis and Frick had orchestrated a quick sale of the Phillies to another buyer.49

Despite this setback, Veeck continued to participate in baseball’s civil-rights movement. In the early 1940s, as owner of the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers, Veeck sat in the “colored” section of the stands during the team’s spring training in Ocala, Florida. The local sheriff and mayor showed up, ordered him to move, and threatened to arrest him for violating Florida’s Jim Crow laws. Veeck refused and threatened to pull the team’s lucrative spring-training program. The local officials left him alone after that.50 In 1947, shortly after Robinson joined the Dodgers, Veeck, who then owned the Cleveland Indians, hired Larry Doby as the AL’s first Black player and moved the team’s spring-training venue from Florida to Arizona.

A little-known episode in the battle to integrate baseball took place in the US military in Europe, led by Sam Nahem, a right-handed pitcher who embraced left-wing politics.51 Nahem pitched for Brooklyn College’s baseball team and played fullback on its football team. At the time, Brooklyn College was a center of political activism, and Nahem began participating in Communist Party activities there. Between 1938 and 1941, Nahem pitched for the Brooklyn Dodgers, St. Louis Cardinals, and Philadelphia Phillies and earned a law degree at St. John’s University in the offseasons.

Like most radicals of that era, Nahem believed that baseball should be racially integrated. He talked to some of his teammates to encourage them to be more open-minded. “I did my political work there,” he told an interviewer years later. “I would take one guy aside if I thought he was amiable in that respect and talk to him, man to man, about the subject. I felt that was the way I could be most effective.”52

During World War II, many professional players were in the military, so the quality of play on military bases was excellent. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the military expanded its baseball program. That year, over 200,000 troops played on military teams in France, Germany, Belgium, Austria, Italy, and Britain.

Many top Negro League ballplayers were in the military, but they faced segregation, discrimination, and humiliation. Monte Irvin, a Negro League standout who later starred for the New York Giants, recalled: “When I was in the Army I took basic training in the South. I’d been asked to give up everything, including my life, to defend democracy. Yet when I went to town I had to ride in the back of a bus, or not at all on some buses.”53 Most Black soldiers with baseball talent were confined to playing on all-Black teams.

Nahem entered the military in November 1942. He volunteered for the infantry and hoped to see combat in Europe to help defeat Nazism. But he spent his first two years at Fort Totten in New York. There, he pitched for the Anti-Aircraft Redlegs of the Eastern Defense Command. In 1943 he set a league record with a 0.85 earned-run average. He also finished second in hitting with a .400 batting average and played every defensive position except catcher. In September 1944, his Fort Totten team beat the Philadelphia Athletics 9-5 in an exhibition game. Nahem pitched six innings, gave up only two runs and five hits, and slugged two homers, accounting for seven of his team’s runs.

Sent overseas in late 1944, Nahem served with an antiaircraft artillery division. From his base in Rheims, he was assigned to run two baseball leagues in France, while also managing and playing for his own team, the Overseas Invasion Service Expedition (OISE) All-Stars, which represented the army command in charge of communication and logistics. The team was made up mainly of semipro, college, and ex-minor-league players. Besides Nahem, only one other OISE player, Russ Bauers, who had compiled a 29-29 won-loss record with the Pirates between 1936 and 1941, had major-league experience.

Defying the military establishment and baseball tradition, Nahem insisted on having African-Americans on his team. He recruited Willard Brown, a slugging outfielder for the Kansas City Monarchs and Leon Day, a star pitcher for the Newark Eagles.

Nahem’s OISE team won 17 games and lost only one, attracting as many as 10,000 fans to its games, reaching the finals against the 71st Infantry Red Circlers, representing General George Patton’s Third Army. One of Patton’s top officers assigned St. Louis Cardinals All-Star outfielder Harry Walker to assemble a team. Besides Walker, the Red Circlers included seven other major leaguers, including the Cincinnati Reds’ 6-foot-6 inch side-arm pitcher Ewell “The Whip” Blackwell.

Few people gave Nahem’s OISE All-Stars much chance to win the European Theater of Operations (ETO) championship, known as the GI World Series. It took place in September, a few months after the defeat of Germany.

They played the first two games in Nuremberg, Germany, in the same stadium where Hitler had addressed Nazi Party rallies. Allied bombing had destroyed the city but somehow spared the stadium. The US Army laid out a baseball diamond and renamed the stadium Soldiers Field.

On September 2, 1945, Blackwell pitched the Red Circlers to a 9-2 victory in the first game of the best-of-five series in front of 50,000 fans, most of them American soldiers. In the second game, Day held the Red Circlers to one run. Brown drove in the OISE’s team first run, and then Nahem (who was playing first base) doubled in the seventh inning to knock in the go-ahead run. OISE won the game, 2-1. Day struck out 10 batters, allowed four hits, and walked only two hitters.

The teams flew to OISE’s home field in Rheims for the next two games. The OISE team won the third game, as the Times reported, “behind the brilliant pitching of S/Sgt Sam Nahem,” who outdueled Blackwell to win 2-1, scattering four hits and striking out six batters.54 In the fourth game, the Third Army’s Bill Ayers, who had pitched in the minor leagues since 1937, shut out the OISE squad, beating Day, 5-0.

The teams returned to Nuremberg for the deciding game on September 8, 1945. Nahem started for the OISE team in front of over 50,000 spectators. After the Red Circlers scored a run and then loaded the bases with one out in the fourth inning, Nahem took himself out and brought in Bob Keane, who got out of the inning without allowing any more runs and completed the game. The OISE team won the game, 2-1. The Sporting News adorned its report on the final game with a photo of Nahem.55

Back in France, Brig. Gen. Charles Thrasher organized a parade and a banquet dinner, with steaks and champagne, for the OISE All-Stars. As historian Robert Weintraub has noted: “Day and Brown, who would not be allowed to eat with their teammates in many major-league towns, celebrated alongside their fellow soldiers.”56

One of the intriguing aspects of this episode is that, despite the fact that both major-league baseball and the American military were racially segregated, no major newspaper even mentioned the historic presence of two African-Americans on the OISE roster. If there were any protests among the White players, or among the fans – or if any of the 71st Division’s officers raised objections to having African-American players on the opposing team – they were ignored by reporters. For example, an Associated Press story about the fourth game simply referred to “pitcher Leon Day of Newark.”

Although Rickey knew Nahem when he played for the St. Louis Cardinals, it isn’t known if Rickey was aware of Nahem’s triumph over baseball segregation in the military. But in October 1945, a month after Nahem pitched his integrated team to victory in the European military championship, Rickey announced that Robinson had signed a contract with the Dodgers.

The protest movement for baseball integration had set the stage for Robinson’s entrance into the major leagues.

PETER DREIER is the E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics and founding chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. He has written or coauthored five books, including “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame” (Nation Books), “Place Matters: Metropolitics for the 21st Century” (University Press of Kansas), and “We Own the Future: Democratic Socialism, American Style” (The New Press). His next book, coauthored with Robert Elias, “Baseball Rebels: The Reformers and Radicals Who Shook Up the Game and Changed America,” will be published in 2022. He writes for the Los Angeles Times, American Prospect, The Nation, Talking Points Memo, and other publications, mostly about politics but occasionally about baseball. He has written profiles of pitchers Sam Nahem and Joe Black for the SABR Biography Project.

Notes

1 Broun repeated his remarks in his syndicated column. Heywood Broun, “It Seems to Me,” Pittsburgh Press, February 9, 1933.

2 Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 5.

3 Robert Ruck, “Crossing the Color Line,” in Lawrence D. Hogan, editor, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington: National Geographic, 2006), 327.

4 Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1944), 21.

5 The protest movement to integrate major-league baseball is discussed in Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983); Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence; Irwin Silber, Press Box Red: The Story of Lester Rodney, the Communist Who Helped Break the Color Line in American Sports (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003); Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1997); Kelly Rusinack, “Baseball on the Radical Agenda: The Daily Worker and Sunday Worker Journalistic Campaign to Desegregate Major League Baseball, 1933-1947,” in Joseph Dorinson and Joram Warmund, eds., Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1998); David K. Wiggins, “Wendell Smith, The Pittsburgh Courier-Journal and the Campaign to Include Blacks in Organized Baseball 1933-1945,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer 1983): 5-29; Henry Fetter, “The Party Line and the Color Line: The American Communist Party, the ‘Daily Worker,’ and Jackie Robinson,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Fall 2001): 375-402.

6 This discussion of Wendell Smith relies on the following sources: Brian Carroll, “A Crusading Journalist’s Last Campaign: Wendell Smith and the Desegregation of Baseball’s Spring Training,” Communication and Social Change 1 (2007): 38-54; Brian Carroll, “‘It Couldn’t Be Any Other Way’: The Great Dilemma for the Black Press and Negro League Baseball,” in Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal 5 (2012): 5-23; Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence; Chris Lamb, “‘What’s Wrong With Baseball’: The Pittsburgh Courier and the Beginning of its Campaign to Integrate the National Pastime,” The Western Journal of Black Studies 26 (2002): 189-203; Ursula McTaggart, “Writing Baseball into History: The Pittsburgh Courier, Integration, and Baseball in a War of Position,” American Studies: 47 (2006): 113-132; Andrew Schall, “Wendell Smith: The Pittsburgh Journalist Who Made Jackie Robinson Mainstream,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 5, 2011; “Wendell Smith, Sportswriter, Jackie Robinson Booster, Dies,” New York Times, November 27, 1972; and Wiggins, “Wendell Smith.”

7 Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sport Spurts: A Strange Tribe,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 14, 1938: 17.

8 Wendell Smith, “‘I’ve Seen a Million!’ – Leo Durocher,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1939: 16.

9 See, for example, Wendell Smith, “‘No Need for Color Ban in Big Leagues’ – Pie Traynor: These Pirates Rate Negro Players with Best in Major Leagues,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 2, 1939: 16.

10 “Dizzy Dean Rates ‘ Satch’ Greatest Pitcher,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 24, 1938: 17.

11 Wendell Smith, “‘Would Be a Mad Scramble for Negro Players if Okayed’ – Hartnett: Discrimination Has No Place in Baseball – These Cubs Agree,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1939: 16; Chris Lamb, “Baseball’s Whitewash: Sportswriter Wendell Smith Exposes Major League Baseball’s Big Lie,” NINE, Volume 18, Number 1 (Fall 2009): 1-20.

12 The Communist Party’s involvement in the civil-rights and labor movements, particularly during the Depression, is discussed in Hosea Hudson and Nell Irvin Painter, The Narrative of Hosea Hudson, His Life As a Negro Communist in the South (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979); Robin Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Robert Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Caroline Press, 2003); August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981); Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004); and Mark Solomon, The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-36 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998).

13 “Batter Up,” Daily Worker, April 18, 1940.

14 “Labor Union to Protest Major League Color Ban at New York World Fair,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 25, 1940: 16: “10,000 at Fair Petition to End Baseball Jim Crow,” Daily Worker, July 25, 1940.

15 John McReynolds, “Nate Moreland: A Mystery to Historians,” The National Pastime, No. 19 (1999): 55-64.

16 Amy Essington, The Integration of the Pacific Coast League (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 36-37

17 Silber, Press Box Red, 151.

18 Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, 37.

19 “ “Paige Beats Big Leaguers,” Daily Worker, May 25, 1942.

20 Dave Zirin, “An Interview with ‘Red’ Rodney,” Counterpunch, April 3, 2004. counterpunch.org/2004/04/03/an-interview-with-quot-red-quot-rodney.

21 “Dimaggio Calls Negro Greatest Pitcher,” Daily Worker, September 13, 1937.

22 Silber, Press Box Red, 144.

23 Silber, Press Box Red, 144.

24 Silber, Press Box Red, 62.

25 Roy Campanella, It’s Good to Be Alive (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1959), 97-98.

26 Cited in Lester Rodney, “On the Scoreboard,” Daily Worker, April 3, 1950.

27 Jules Tygiel, Extra Bases (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 69.

28 Cited in Ethan Mitchell, The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), 244.

29 James G. Thompson, “Should I Sacrifice to Live ‘Half-American?’” Pittsburgh Courier, January 31, 1942: 3; Doron Goldman, “The Double Victory Campaign and the Campaign to Integrate Baseball,” in Marc Z Aaron and Bill Nowlin, eds., Who’s On First? Replacement Players in World War II (Phoenix: SABR, 2015), 405-8. sabr.org/research/article/goldman-double-victory-campaign-and-campaign-integrate-baseball.

30 For example: Fay Young, “Challenge to the Big Leagues: Barring of Negro Players in Major Leagues Flouts Democratic Ideals of War,” Chicago Defender, September 26, 1942.

31 “Labor Calls On Landis to Remove Color Ban in Major Leagues,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 13, 1942: 15; “Seamen Demand Landis Lift Ban,” Daily Worker, June 5, 1942; “Removal of Baseball Jim-Crow Against Negroes Sought by Strong White Forces,” Atlanta Daily World, June 7, 1942; “Organized Labor Joins Fight on Major League Bias: Judge Landis Petitioned by Unions 2,000 Maritime Workers, Wholesalers Ask for Justice,” New York Amsterdam News, June 13, 1942; “Color Ban In Baseball Hit by Packinghouse Men,” Chicago Defender, July 11, 1942.

32 “Czar Landis Denies Rule Against Negroes in Majors,” Austin Statesman, July 17, 1942; “You May Hire All Negro Players, No Ban Exists, Landis Tells Durocher,” New York Herald Tribune, July 17, 1942.

33 “Drive on Jim Crow Gains Momentum,” Sunday Worker, June 28, 1942.

34 “No Baseball Rule Against Hiring Negroes – Landis,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, July 17, 1942; Henry D. Fetter, “The Party Line and the Color Line: The American Communist Party, the Daily Worker and Jackie Robinson,” Journal of Sport History, 28 (Fall 2001): 375-402; Henry D. Fetter, “From ‘Stooge’ to ‘Czar’: Judge Landis, the Daily Worker and the Integration of Baseball,” American Communist History, 6:1 (2007): 29-63.

35“Landis Denies Audience to Negro Group,” Detroit Free Press, December 4, 1942; “CIO’s Request to Ask Majors to Hire Negroes Turned Down,” Hartford Courant, December 4, 1942; “Landis Rebuffs Plea for Negro Play in Majors: Asks Fair Play for Ball Stars/Bob Considine, Famous White Sports Writer, Urges Negro Players Be Given Their Chance,” New York Amsterdam Star-News, December 12, 1942.

36 “Wrigley Sees ‘Negroes in Big Leagues Soon’: Cubs’ Owner Says It Has ‘Got To Come’/Would Put Negro Player on His Team if Fans Demanded Same,” Chicago Defender, December 26, 1942; Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence, 218-221.

37 “Send Resolution on Negroes in Major Baseball To FDR,” Chicago Defender, February 20, 1943; Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence, 221.

38 Wiggins, “Wendell Smith,” 21.

39 Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence, 235.

40 Silber, Press Box Red, 83; Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson (New York: The New Press, 1995), 282-283.

41 Wendell Smith, “Publishers Place Case of Negro Players Before Big League Owners: Judge Landis Says No Official Race Ban Exists in Majors,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 11, 1943: 1; “Robeson Sees Labor as Salvation of Negro Race: Praises CIO Plan to Better Racial Conditions Here,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 25, 1943: 11.

42 Ric Roberts, “Chandler’s Views on Player Ban Sought: New Czar Must Face Bias Issue,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 5, 1945: 12.

43 “Two Negroes Are Tried Out by the Dodgers but They Fail to Impress President Rickey,” New York Times, April 8, 1945.

44 Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, 69.

45 Ron Fimrite, “Sam Lacy: Black Crusader a Resolute Writer Helped Bring Change To Sports,” Sports Illustrated, October 29, 1990.

46 Bill Nowlin, Tom Yawkey: Patriarch of the Boston Red Sox (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018); Bill Nowlin, ed., Pumpsie & Progress: The Red Sox, Race, and Redemption (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2010).

47 There is some dispute about this. Veeck wrote about his plans, and Landis’s and Frick’s efforts to thwart them, in his biography, Veeck as in Wreck. A 1998 article claimed that Veeck’s intention to buy the Phillies in order to integrate baseball is simply not true. See Larry Gerlach, David Jordan, and John Rossi, “A Baseball Myth Exploded: Bill Veeck and the 1943 Sale of the Phillies,” The National Pastime, Vol. 18 (1998). sabr.org/research/article/a-baseball-myth-exploded-bill-veeck-and-the-1943-sale-of-the-phillies/. The eminent baseball historian Jules Tygiel rejected Gerlach, Jordan, and Rossi’s claims. See Jules Tygiel, “Revisiting Bill Veeck and the 1943 Phillies,” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 35 (2007): 109-114. research.sabr.org/journals/files/SABR-Baseball_Research_Journal-35.pdf. In his biography of Veeck, Paul Dickson makes the case that Veeck’s version of the story is true. Paul Dickson, Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker & Company, 2012), 79-83, 356-366.

48 Dickson, Bill Veeck, 79.

49 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck – As In Wreck (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962); Dickson, Bill Veeck, 80.

50 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck – As In Wreck; Peggy Beck, “Working in the Shadows of Rickey and Robinson: Bill Veeck, Larry Doby, and the Advancement of Black Players in Baseball,” in Peter M. Rutkoff, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1997 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2000).

51 This draws on my profile of Sam Nahem: Peter Dreier, “Sam Nahem,” Society for American Baseball Research, n.d., sabr.org/bioproj/person/focoboef; and Peter Dreier, “Sam Nahem: The Right-Handed Lefty Who Integrated Military Baseball in World War II,” in William M. Simons, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2017-2018 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2019).

52 Joe Eskenazi, “Artful Dodger: Baseball’s ‘Subway’ Sam Strikes Out Batters, and With the Ladies Too,” J Weekly, October 23, 2003. jweekly.com/article/full/20827/artful-dodger.

53 Quoted in Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1964), 105.

54 “Oise Nine Beats Third Army,” New York Times, September 6, 1945.

55 All Stars Win European Title in GI Playoff,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1945: 12.

56 Robert Weintraub, The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Little Brown & Co., 2013).