Bernice Gera and the Trial of Being First

This article was written by Amanda Lane Cumming

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

On June 24, 1972, Bernice Gera became the first woman to umpire a professional baseball game. Immediately after the game ended, she quit. She fought baseball for five years for the chance to umpire a professional game. Why fight so long for an umpiring career, just to give it up after one game?

We think of pioneers as being stoic, strong, and preternaturally gifted at the thing they are pursuing. Although she was the first woman umpire, Gera’s story isn’t really about her determination to become an umpire. She was just a woman standing in front of organized baseball, asking it to accept her.

BELONGING AND BASEBALL

Bernice Gera was born Bernice Marie Shiner on June 15, 1931, in Ernest, Pennsylvania. Her parents divorced when she was two years old and abandoned their five children. Bernice and her siblings moved frequently growing up, being passed from relative to relative. Baseball became an anchor for her throughout her childhood tumult.

“Wanting to belong is one of the most powerful things in the world,” she said. “That’s why sports are so popular. Just rooting for a team makes you feel part of it.”1 The first team she wanted to join was her older brothers’ team. She got a chance when she was eight years old. One of the players didn’t show up for a game and the boys reluctantly allowed her to fill in for him in the outfield. One of her brothers, Henry Shiner, said years later, “Eventually after we saw her hit, we let her on the team. She became quite a hitter. Then everybody wanted her.”2

There weren’t any opportunities for her to play baseball as she got older, so she began playing softball. After graduating from high school in Erath, Louisiana, in 1949, she married Louis Thomas Jr. and moved to New York. She worked as a secretary, but baseball was never far from her mind. She said of balancing her work and baseball life, “No matter where I worked as a typist, I would always be more interested in what was happening to the Dodgers. Quite a few times I was almost fired because of it. Instead of cranking out a letter, I’d have the drawer of my desk open, listening to the Dodgers on the radio.”3

Her childhood gave her a lifelong love for baseball and imbued in her a desire to help children. After her day job, she taught kids to play baseball in parks and community centers. She participated in events to benefit children’s’ charities. During these events, she would get a chance to flex her own baseball muscle, putting on hitting demonstrations with male baseball players, including major leaguers Roger Maris, Cal Abrams, and Sid Gordon.4

A newspaper in Louisiana printed a picture of her with Roger Maris, following a demonstration they participated in at Coney Island in 1961.5 Several newspapers crowed that she could hit a baseball 350 feet.6 One anointed her “The world’s foremost female baseball player.”7 She hit the newspapers again in 1966 and Ripley’s Believe It Or Not in 1967, after she was banned from the concessions at Rockaway and Coney Island for cleaning out the prizes in the throwing booths. Her prowess won more than 300 stuffed animals, which she donated to children’s hospitals and charities. “Everything I do in baseball is aimed at helping children,” she explained.8

At some point she divorced Thomas. In 1964, she married Steve Gera, a photographer, and settled in Jackson Heights, Queens. Before their marriage, he didn’t know much about baseball, but Bernice changed that. “We watch it and talk about it night and day,” she said of his conversion into a baseball fan.9

Gera fostered an intense desire to be part of baseball. She sent inquiries to every major league team, asking for a job. Every team declined. “At first I just tried to get a job with any club, doing anything,” she said. “I would have sold peanuts if they wanted me to. But the answer was negative all the way around. I waited three months for one team to answer. And would you believe that I stayed up nights praying for it to come through? When they said no, I decided to become an umpire.”10

BECOMING AN UMPIRE

At 2 o’clock one morning in 1966, Bernice Gera sat up in bed. She had been feeling dejected about not finding a job in baseball, when it suddenly hit her. She would become an umpire. Steve, she said, “choked on his coffee when I told him the next morning.”11

The list of women umpires before Gera was short. The first professional female umpire was Amanda Clement, who worked semi-pro games in the early 1900s. In 1943, the National Baseball Congress, a semi-pro league, hired a woman named Lorraine Heinisch to umpire one game of their national tournament.12 Otherwise, baseball officiating remained a male bastion.

Her first obstacle was to get into an umpire school. She applied to, and was accepted at, the Al Somers School for Umpires in 1967. Somers had interpreted her first name as “Bernie.” When she called to ask a question, he realized his mistake. Gera said, “He blew his cool. He told me there never had been a woman in his umpire school, and there never would be.”13

Gera was finally accepted at the National Sports Academy in West Palm Beach, Florida. She was initially dismissed because the school didn’t have any accommodations for women. She called them, agreed to live away from the school, and begged them to accept her. Eventually, she was accepted to the academy.14

Her acceptance into umpire school launched a thousand sexist newspaper columns from sportswriters objecting to a woman breaking into baseball’s masculine stronghold. Many writers tried their hand at fiction and imagined what baseball would look like with a woman umpiring. One example from Will Grimsley with the Associated Press imagines Gera arriving late because she had been at the hairdresser. Then, she admonishes Carl Yastrzemski for cursing after a strike call, reminding him he is in mixed company. She blows kisses to the crowd, pauses the game to re-apply lipstick, and gets all the ball and strike calls wrong.15

Red Smith wondered about, and guessed at, her measurements.16 Lance Evans, sports editor of The Express, fretted about how ball players could possibly keep their eyes on the ball when the batter “is going to have to start looking at the curves that are attractively arranged behind him.”17 One of the more bizarre entries came from Dick West who, in a UPI wire story that ran in papers across the country, addressed the emergence of a woman umpire by imagining a pre-game interview with William Shakespeare. In a question-and-answer format the Bard commented on Gera’s foray into umpiring and offered a little advice to managers dealing with a woman umpire: “That man that hath a tongue, I say, is no man if with his tongue he cannot win a woman.”18

In June 1967, Gera began umpire school. After her first week in the six-week program, the Miami News sent a reporter to write a feature on her. The story paints a picture of Bernice as being somewhat naive, but quickly learning the umpiring trade. Her instructor, Jim Finley, had nothing but praise for her abilities and said, “I’ll certainly recommend her for a professional job.”19

The story didn’t offer a perspective on the difficulties Gera was facing. Umpiring school for her wasn’t just about mastering the rules of baseball or learning how to position herself for plays. She was the only umpire training at the baseball school, which made her doubly alone, as both a woman and an umpire. After two weeks of driving 50 miles round trip each day, she was given permission to live in a dormitory on campus with about 40 male baseball players and coaches. At night, the men would throw beer cans and bottles at her door. She tried to tough it out but spent the last week of her session living off campus to escape the torment.20

While living away from the school, she had to put her umpiring gear on in the parking lot, trying to shield herself in the car. “Once a bunch of men stood on the hoods of their cars to take pictures.”21 They also made learning difficult for her on the field. She said, “When I first started in umpire school, I used to just say ‘strike’, but the men went prancing around saying, ‘Oh my goodness, a strike!’ So I learned to bawl it out: STEE-RIKE!”22 The players and umpires hired to assist in games would catcall her and badger her. “Other umpires and players ask me to go out after the games,” she told a reporter in 1969. “Some are just trying to shake me up. But if an umpire asks me before the game and I refuse, I worry about them not working with me on the field.”23

“The first day at umpire’s school was the roughest I ever had,” she recalls. “They put me out there in a game before I knew what to do. The kids put six or seven balls in play and they would try to hit me with the warmup balls when my back was turned.”24 Players would tease her after calls. She recalls runners winking at her after she called them safe and saying, “Bad call. I was out.”25

“I got all the curse words in the book,” Gera said. “And a lot not in the book. Four letter words. They didn’t want me on the field. It all hinged on whether I could take it. I took it. But after, I’d go home and cry like a baby.”26 She got through school by repeating her umpiring mantra to herself: “Keep cool all the time.” “Things changed when I learned what I was doing, but there still was an awful lot of resentment.”27

The men in umpire school weren’t the only hostilities she encountered. The chest protector also became a point of contention. Due to her small stature, she needed to wear a chest protector that was strapped to her, rather than holding one in front. But the chest protectors were all made with men in mind. Finding one that would fit passably was a battle, and one that male sportswriters spent a lot of time and column inches discussing.

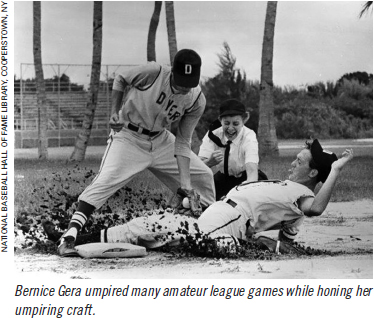

She graduated from umpire school in July 1967. All the minor leagues were underway, so while she looked for umpiring work for the 1968 season, she began a series of umpiring jobs to get experience outside of school.

Her first appearance was at the National Baseball Congress Tournament—the same tournament that hired Lorraine Heinisch in 1943—that August. The tournament organizers saw the publicity benefit of having her umpire a game, so they brought her in for the opening game and promoted her appearance. She was assigned to work third base on a full four-umpire crew and only had to make a few calls before her duties were done. Later that summer she would umpire for the American Legion, Little League, and the semi-pro Bridgeton Invitational Tournament.

Between her graduation and first umpiring gig, she appeared on The Tonight Show, The Johnny Carson Show, and as a guest of Joe Garagiola, the former major league catcher turned TV host, on The Today Show. It was clear the public was fascinated by the woman barging into baseball.

THE LEGAL FIGHT BEGINS

With an umpire school diploma in hand and umpiring game experience under her belt, Bernice Gera applied for jobs in professional baseball. She wrote to Ed Doherty, the head of umpire development.28 When she did not receive a response, she wrote again. She never heard back, so she contacted the Commissioner of Baseball, William D. Eckert. She wrote to him, then followed up by phone. Eckert simply washed his hands of the situation, telling her Doherty oversaw umpires.29

Having been rejected by baseball before, Gera was determined to succeed this time. She knew they were ignoring her because she was a woman. She decided to take her case to the courts. In April of 1968 she retained the services of Mario Biaggi, who would be elected to represent the Bronx in the US House of Representatives later that year. He filed the case with the New York State Division of Human Rights on April 30, 1968. The complaint charged that Commissioner Eckert “stated in words or substance and by his acts and his comportment that he objects to a female umpire in organized baseball.”30

The Commissioner’s office responded with a statement that the Commissioner did not handle the hiring of umpires and that she must contact the president of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (the minor leagues) or the American and National League presidents to seek employment as an umpire. In June 1968, the Human Rights Division found Commissioner Eckert not guilty of discriminatory hiring practices because he was not directly in charge of umpire employment.31

The legal action touched off another round of sports columns. Bill Bondurant, sports editor of the Fort Lauderdale News, begs in a column titled “Baseball Threatened by Female,” “Please, Bernice, don’t sue. What have men left to themselves? You women are in our saloons and on our golf courses. You wear trousers just like ours and some crazy guy on television keeps offering you cigars. Let us keep baseball. It isn’t much, we know, but it’s almost all we have left.”32

An unattributed item in many papers opined, “If women started umpiring, players might feel constrained to start acting like gentlemen…Baseball can do without that. It needs more rhubarbs and catcalls, more discontent and threats of mayhem; it needs that old Gas House Gang spirit. But with a lady umpire…?”33

Bill Clark wrote in a column that ran in the Montana Standard, “Suppose you had to put the run on Durocher. You could, huh? Baby, you don’t know what rhubarb is til you’ve sampled his recipe. And you couldn’t exercise the time-honored feminine prerogative and change your mind every two minutes.”34

Bob Quincy suggested in The Charlotte News, “If Bernice wants to associate with baseball players, the least she can do is shower with them. This, in itself, would bring about a speed-up of the game. The real fun would develop in the locker room.”35

Bill Hodge, sports editor of The Wichita Eagle argued, “Sometimes a little discrimination is a good thing…They need a woman umpire in the major leagues right now like our barber shop needs a male manicurist.”36

In the Chicago Tribune David Condon whined that “Mrs. Gera is entitled to invade the domains of umpires only after the courts rule that Gale Sayers, Ron Santo, Tony Skoronski, and Ziggy Czarobski are fairly entitled to employment as Playboy Bunnies.”37

The Star Tribune’s Charles M. Guthrie went to a dark place: “If women ever become umpires it will mark the doom of baseball…the game will get pallid and fans will stay home.” An unattributed item in the El Paso Herald-Post agrees, “Should ladies take up position behind home plate, the game perhaps would survive. But it would no longer be recognizable as baseball.”39

It was simply unfair to men for a woman to become an umpire, argued John P. “Moon” Clark in The Daily Republican, “Calling strikes and fouls and balls has always been a man’s job because he never gets a chance to do anything like that in his own home. Umpiring baseball games has always been left to a man. It gives him the one big chance to take over and boss the field, so to speak.”40

While the columnists typed their sexism, Gera contacted every minor league to seek employment. After receiving either a rejection or no response from each, she zeroed in on the New York-Pennsylvania League, a Class A league close to home. The NY-P League president Vincent M. McNamara had rejected her request by writing that she would not be considered for a job because the ballparks did not have appropriate dressing rooms for her to use. Furthermore, in baseball “tempers sometimes reach the boiling point” that results in language that “beyond the hearing of the spectators, is of a nature that one would not relish having one’s mother or sister or any lady exposed to.”41

Doherty, the aforementioned head of umpire development, offered the defense that she was ineligible for hire because the umpire development program required “applicants be 21 to 35 years old, a minimum of 5-10 tall, and weigh at least 170 pounds, with perfect vision of course.”42 At the time, Gera was 37 years old, 5’2″, and weighed about 125 pounds. These were an odd pair of reasonings to avoid hiring a woman. McNamara’s seemed to be a clear-cut case of gender discrimination and Doherty’s would require a robust justification. It would have been an easier path to simply dismiss her qualifications or give her a tryout and say she didn’t measure up.

The tide in the broader sports world was beginning to change at the same time. In February 1969, Diane Crump became the first woman jockey to ride in a pari-mutuel (gambling) race. It required track officials to threaten suspensions to any male jockeys who boycotted the race, and a police escort from the jockey’s quarters to the paddock at Hialeah Park in Florida.43 Later that month, Barbara Jo Rubin became the first woman jockey to win a race. The walls were coming down, but baseball was determined to brace them.

THE FIRST CONTRACT

With McNamara’s rejection, Biaggi went back to the Human Rights Division with a new complaint on March 19, 1969. A hearing in the case had been postponed several times when McNamara contacted Gera in June 1969 to offer her the opportunity to formally apply for a job. He warned her that all the umpires had been hired for the season, so she wouldn’t be considered until 1970. Then, McNamara changed his mind and sent her a contract and offered her employment for the last month of the short season.

Gera found out she was being offered the job as she watched Apollo 11 land on the moon on July 20, 1969.44 The league usually used two-man umpire crews, but she would be added as a third umpire. She began to make plans to head upstate with her husband and a few friends for her professional debut.

If it seems like that happened too easily to be true, it’s because it was. Later court documents indicated that McNamara only sent her a contract to take some of the pressure off himself. He said “he felt that he had to execute the contract despite her lack of qualifications knowing that [Phil] Piton (the President of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues) would have to make the final decision.”45

On August 1, 1969, Gera was supposed to make her umpiring debut. The sports pages ran stories about Smokey Drolet considering legal action after being denied an opportunity to drive in the Indy 50046 and Elinor Kaine fighting to be allowed in the press box to cover a football game as a reporter.47 But instead of carrying the story of Gera’s debut, they broke the news that she would not be making history after all. Her contract had not been accepted by the National Association.

“I disapproved her contract with the NY-P League,” Phil Piton told reporters. “I don’t wish to comment further at this time.”48 McNamara didn’t express any remorse for the change of events. “I’m not the final word. Mr. Piton only exercised the duties of his office and acted within his right. It’s his job to uphold professional baseball and the national agreement…This is professional sports, and in professional sports you have your ups and downs and you have to take a few lumps along the way.”49

Gera was dejected. “I just can’t get to first base… It’s a strike out, but I will come up again. The game’s not over.”50

THE LEGAL BATTLE CONTINUES

The latest twist in Gera’s quest caught the ear of Representative Samuel Stratton of New York. Incensed at what he saw as clear discrimination, he told reporters he would request that the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the US Department of Justice look into the disapproval of her contract.51 He warned on the House floor that baseball’s refusal to end sex discrimination “could have devastating economic effects on baseball itself.”52

Gera’s lawyer, Mario Biaggi, also a member of Congress, threatened further investigations into the sport’s business: “Due to the conduct of baseball in this matter, which tends to be illegal, there might be other areas that also are illegal.”53

Still another member of Congress got in on the action. Rep. Martha W. Griffiths, who championed antidiscrimination laws based on sex (and would introduce the Equal Rights Amendment to the House), joined the chorus of powerful voices in support of Gera. At a press conference, Gera was asked if she could handle a Casey Stengel or a Leo Durocher, famously grumpy major league managers. Griffiths answered the question for her, snapping, “The real question is whether Casey or Leo could hold their own against her. Baseball is protecting them, and losing a chance to increase attendance and make some money.”54

Attendance had become a big concern in baseball, as the NFL in particular, began to grow in popularity.55 Baseball resisted changing with the times and burrowed into tradition rather than evolve. Gera was a threat to tradition, so rather than admit baseball needed to change, critics claimed she was out to destroy baseball. In response, Gera could only reiterate, “I wouldn’t do anything to hurt baseball. All I want is a chance.”56

Even newspaper columnists had to reluctantly admit that the law was not on the side of baseball remaining exclusively male. But the economic argument, they felt, was on their side. Particularly in the minor leagues, with small budgets and the line between success and financial failure always thin, how could teams take on the added expense of providing appropriate accommodations for a woman?

Bob Whittemore, a columnist for the Oneonta Star, pointed out that “special arrangements were made for her to travel, for her to have a private room instead of sharing one, for special showers and locker facilities in each park. And for a three-person umpiring team with which she was to work…It stands to reason, therefore, that the additional expense involved with Mrs. Gera’s becoming an umpire in the NY-P league could mean the difference between each club’s writing with red or black ink in their ledgers.”57

Stratton wrote to the paper after reading Whitte-more’s column. In addressing the problems of economics, he said those same issues were used to discriminate against women from World War II all the way up to the women jockeys. “It may cost a bit more to end discrimination, either by color or sex. But in the long run it is worth it, and it also happens to be the law of the land.”58

For Gera, something that had begun as a way for her to be involved in baseball had become much bigger. Women’s organizations began to take notice. They sent her support, and asked for hers in return. Gera, however, wasn’t interested in officially joining. “I want to win this without marches. I do not believe in it. I love baseball too much to give it a bad name,” she said.59 “I don’t agree with them on a lot of things. I don’t believe in putting men down.”60

Gera’s hearing before the Human Rights Appeal Board was postponed several times and it wasn’t until April 1970 that the case began to move forward again. The National Association argued that she was not eligible for employment as an umpire because she did not meet the required 5’10” and 170 pound size. The Appeal Board ruled that the physical size requirements were arbitrary and directed the National Association to revise the standards within three months. Then, they were to reconsider Gera based on the revision.

But the National Association continued to fight the case. It appealed the case up the legal ladder to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York. There, the National Association argued in February 1971 that she “wouldn’t be hired even if she were a man.”61 They also said the umpire school she attended wasn’t accredited at the time she was a student.

A month after those arguments, Gera announced that she was filing a $25 million lawsuit against organized baseball, separate from the complaint to the Human Rights Division. Biaggi told a press conference that baseball had “virtually destroyed her career as a baseball umpire.”62 The suit named Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn, the New York-Pennsylvania Baseball League and Vincent M. McNamara, its president; and the National Association of Professional Baseball leagues and its president, Phillip Piton.

Then 39 years old, Gera told reporters, “I’ll keep trying until I’m 80.”63

In April 1971, the Appellate Division issued an opinion in the case of New York State Division of Human Rights v. New York-Pennsylvania Professional Baseball League. The appeals court confirmed the previous order of the Human Rights Appeal Board that organized baseball had indeed discriminated against Gera because of her sex.

Once again, the NY-P League and the National Association appealed the ruling. On November 22, 1971, both sides submitted written arguments. Baseball continued to argue that Gera was not discriminated against because of her sex, although they still argued baseball was no place for a woman. It was mainly her physical size and because she had demonstrated a “proclivity for publicity” which made her “temperamentally unfit for professional umpiring.”64

She certainly was a fixture in the press. Reporters called constantly, and she patiently sat through interview after interview, explaining her qualifications and her deep desire to work in baseball. She was also hired for many speaking appearances. She said she always donated her speaking fees to help kids in need. But baseball wasn’t concerned about her financial compensation for speaking, nor did it matter to them that a woman fighting the patriarchal baseball machine was media fodder, whether she wanted the publicity or not. Her very presence in the media showcased baseball’s indefensible stance that they were purposely keeping women out of the game, so they had to turn it around on her.

On January 13, 1971, the appeals court affirmed the order of the lower court that baseball was engaging in sex discrimination and needed to revise its physical standards for umpires.65 Baseball had twice appealed the ruling of the Human Rights Division, and twice been denied. They still had the option of continuing to appeal, but decided it wasn’t worth it.

In April 1972, the NY-P League sent her a one-year contract. This time, the contract was approved by the new National Association President Henry J. Peters. She would make her umpiring debut when the New York-Pennsylvania League season opened in June, a week after she turned 41, and nearly five years after she graduated from umpire school.

ONE FIGHT ENDS, ANOTHER BEGINS

“All through this case my heart was broken. I’ve always wondered if this was worth it,” Gera said, reflecting on the legal fight.66 “You’ve come a long way, baby, I tell that to myself. But it hasn’t been easy.”67

Although she was happy to have won the opportunity to finally become an umpire, she was exhausted. “It’s cost me about $30,000 in income I never made,” she told reporters. “I had been doing secretarial work until I started umpiring, so that’s five years at a minimum of $5,000 a year, plus my phone bills and other expenses. My legal fees I don’t know yet. Mario Biaggi, the Bronx congressman, took the case because nobody else would…right now I’m broke financially and I won’t get rich as an umpire.”68

Gera said her hair had turned gray, and she had lost patches of hair from the stress of fighting baseball. She tried to be fair to baseball when talking to the press, saying, “They were strong in their beliefs that baseball was and is always going to be a man’s game. I believed just as strongly that baseball is our national pastime, and that means for women as well.”69

She didn’t have much time to dwell on that as the game approached. In addition to constant interview requests, Gera received stacks of letters every day. Many people were writing to send her support, others were young girls who wanted to work in baseball someday too. And then, there were the telephone calls. She would answer the phone and hear, “Don’t you dare take the field.”70

She worried about whether the other umpires would accept her. “Umpiring is a team job. I keep asking myself, ‘Are the guys going to work with me as a team?’ They can hang you if they want to.”71 She was confident, however, in her ability to handle managers and players. “I’ve asked for the job and feel I’m capable of handling myself. I’m not afraid to thumb a manager or player if they get abusive.”72

She was assigned to umpire the opening game between the Geneva Rangers and the Auburn Phillies on June 23, 1972, at Shuron Park in Geneva, New York. Geneva sold 3,000 tickets, a sellout, for the opening game after her assignment was announced. She was set to umpire games in Williamsport and Oneonta after her stint in Geneva, and those parks saw increased ticket sales as well.73

On June 21, Gera was invited to attend the seasonopening welcoming dinner for Geneva. She gave a short speech, saying to the crowd, “I’m grateful to God, grateful to baseball and Friday night is going to be the happiest moment of my life.”74 One of her sisters and her husband, Steve, had accompanied her to Geneva, planning to spend a week of vacation watching her umpire games. “I’m happy for Bernice. It’s been a long struggle for her. She loves baseball so much and wanted so much to be a part of it that she went for umpiring. It isn’t going to be a bed of roses but I feel she’ll make the grade,” Steve proudly predicted.75

The attention was starting to feel a little overwhelming. “I’m trying not to get overly excited,” she said, “but NBC is here now, and CBS and ABC are coming, plus all those reporters. One of them told me I’ll be getting more coverage than President Nixon.”76 (And much like Bernice, even more media scrutiny was on its way for Nixon; burglars had just been caught breaking into the Watergate complex.)

On June 23, the morning of the game, Gera attended an umpires’ meeting. Although she had fought for five years to get there, the meeting brought the enormity of the remaining journey crashing down on her. She said later, “I could sense their resentment. They acted like they didn’t want me around baseball. It was that old male chauvinism once more.”77

After five years, she was tired of fighting baseball, tired of trying to convince baseball that she belonged. After the six hours with the other umpires, she decided she was done fighting. She felt overwhelmed with frustration and the barriers that still firmly stood, even though she had legally knocked them down. “I could beat them in the courts, but how do you change peoples’ attitudes?” she wondered.78

Unfortunately, her historical moment would have to wait a day. Remnants of Hurricane Agnes (then the costliest hurricane in US history) had been ravaging the eastern US. The Geneva area was heavily affected by rain and flooding. The opener was delayed and would be made up the next day in a doubleheader.

Friday night in her motel room, she heard men outside drinking and causing a commotion, talking about the woman umpire. If she had any doubts about her decision to stop umpiring after the first game, this drove it home. “I wasn’t scared off,” she explained. “I was just disgusted. I was fed up with it.”79

THE GAME

The next morning, Gera packed her bags and considered not working the game at all, “but friends and relatives talked me into it because I’d come that far.”80 Her umpiring partner, 24-year-old Doug Hartmayer, picked her up at the motel so they could drive to the game together. Gera said she tried to discuss signals and the game with him, but he refused to speak with her.81

At the ballpark, she declined pre-game interviews with the menagerie of press in attendance. Several reporters noted that she was visibly nervous before taking the field. Assigned to work the bases, Gera ran out to her place on the field as the sellout crowd cheered. A group of girls in the bleachers held up a banner made from a bedsheet with “Right on, Bernice” printed on it.82 Television cameras and photographers were squeezed in down the foul lines.

Because of the doubleheader, the games were each scheduled to go only seven innings. Although she was nervous, the first three innings of the game went fairly smoothly. She made a handful of calls at first and second base. Each call was cheered by the crowd. So far, it was a benign beginning.

With one out in the top of the fourth inning, the fears of Bernice and the warnings about allowing women into baseball converged. With a runner on second base, the batter hit a line drive to the second baseman. The second baseman threw to the shortstop covering the base and caught the baserunner off the base. Forgetting the force play, Gera signaled safe. Then, realizing her mistake reversed her call and indicated the runner was out.

Auburn Phillies manager Nolan Campbell came storming onto the field for an explanation. Gera told him she had made a mistake and forgotten about the force in effect for the runner going back to second base. “He came yelling,” Gera said later, “but he didn’t curse me. I let him go on because he was right, no question about it. I made a mistake and I admitted it.”83

“That’s two mistakes you’ve made!” Campbell yelled. According to Campbell, he followed up with, “The first one was putting on your uniform.” Gera remembers it differently. In an interview a few days after the game, she said he yelled, “The first mistake was you should have stayed in the kitchen peeling potatoes.”84

Gera immediately ejected him from the game, explaining, “Then he was judging me as a woman, instead of as an official.”85 Campbell exploded, “Why throw me out because you made a mistake?” he shouted. He refused to leave the field and stalked behind her as she went back to her post on the first base line. “You’re not only a woman, but you’ve got a quick temper. You can’t run somebody out of a game just giving you a little guff.”86 He eventually stomped off to the dugout, refusing to go into the clubhouse as he was supposed to. “I was going to make her come and throw me out,” he explained later.87

Throughout the dispute, Gera’s partner Hartmayer stayed behind home plate and did not intervene. “That was her problem,” he shrugged later.88 After Campbell refused to go into the clubhouse, Hartmayer finally intervened. His only involvement in the dispute was to put an arm around Campbell and assist him in leaving the game.

After the excitement of the ejection, the game went on. After Gera called out a Geneva baserunner for oversliding the base, she drew complaints from Geneva manager Bill Haywood. Then, after calling a runner safe at first base, the Auburn pitching coach, who had taken over for Campbell, gave her an earful. She was ridiculed for not understanding the procedures for assisting with pitching changes.89

If she had ever doubted her decision to only umpire one game, Campbell’s comment about peeling potatoes and her umpiring partner’s refusal to work with her must have reinforced the decision. When the game ended with a 4-1 Geneva win, she was ready to leave baseball.

She walked straight off the field and found Geneva general manager Joseph McDonough. She told him she was done. “I’ve just resigned from baseball. I’m sorry, Joe.”90 She hurried out of the ballpark, into a waiting car, and away she went, her umpiring career over.

As she drove back to Queens, the ballpark in Geneva was thrown into chaos. McDonough went to her motel to intercept her, only to discover she had already checked out. An announcement was made to the shocked crowd before the second game of the doubleheader. An umpire happened to be in the stands and agreed to work the bases so the game could go on.91 In the middle of the first inning, the game was postponed when it began to rain. It was just as well because all the press cared about was figuring out what had happened to Gera.

Auburn manager Campbell was eager to talk about her game. “I hardly did anything. I used ‘hell’ once or twice and I was out of the game. I told her ‘you’re not only a woman, but you have a quick trigger, too’. They should never have let her in the league,” he pontificated. “Women don’t have the strength to withstand the pressure. This is a man’s game and it always will be.”92

Campbell, who had been ejected nine times the previous season, commented to Frank Dolson of the Philadelphia Inquirer (who referred to him as “Noley” in his column), “I hope nobody blames me for her quitting. I think she made up her mind, the first person who came out, she was going to run him. It had to be me, that’s all. I sure as hell don’t want to be made the scapegoat.”93

Gera’s partner, Hartmayer, couldn’t wait to chat with reporters about her performance. “It didn’t surprise me that she quit. I don’t even know why I want to be an umpire,” he joked, “let alone why a woman would. She was just scared to death.”94

“It wasn’t a hard game to umpire, really. You could see she just didn’t have it. I’ve been chewed out more than that in Little League,” Hartmayer said, referring to Campbell’s tirade.95 “Saying you’ve made a mistake is very unethical in our profession. That’s one thing you never do. You never reverse yourself,” he chided, then charitably added, “Otherwise I don’t want to say too much about her game. I don’t want to come down too hard on her.”96

In response to her quitting, the newspaper columns shifted away from hand wringing over a woman daring to break into baseball into hand wringing over the ways she had harmed the women’s movement. The Journal News wrote, “The battle for acceptance was not finished, but just beginning, and she let down a lot of people—not only women—by not persisting through the main event.”97

The Charlotte Observer was disappointed, writing:

…she carried the hopes of many who feel that women deserve the right to work in any job where the qualifications are, or ought to be, based on ability, not sex. She was a pathfinder, a barrier-breaker…

To the skeptics, all she proved was her own instability. She showed the world a quitter and gave those who question the emotional capabilities of women who try to work in a “man’s world” more ammunition to use in their resistance to equal rights for women.

Many people take their baseball games too seriously to pardon Mrs. Gera’s erratic behavior. We only hope they do not equate her umpiring antics with the more serious and significant advances being made by women in business and politics.98

Other papers trotted out the examples of Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby to exploit and distort their struggles in order to illustrate Gera’s failures and place the blame for failing to single-handedly change society on her own weakness. The Star Tribune wrote, “We wish Mrs. Gera hadn’t given up so quickly. After all, if Jackie Robinson had quit under pressure in his rookie season, think of what a serious blow this would have been to the efforts of black players to break the Jim Crow tradition in baseball.”99

There was no introspection, no contemplation over how baseball could be more welcoming to people who weren’t allowed inside. Vinny DiTrani of The Record was typical of those who brought up Robinson. “There are a lot of deep-rooted prejudices in baseball, just as in any institution. They have to be eliminated, of course, but it takes time.”100

Time, it only takes time. And, apparently, a pioneer willing to endure abuse while time ticks by.

The week after her game, Gera finally spoke to the press. She gave her side of what happened in Geneva, from the umpires meeting to the confrontation with Campbell, and admitted she had planned to quit after the first game that day.

She tried to explain the exhaustion she felt and the way her fight against baseball had utterly worn her down. At one point she said, “If they don’t want women in baseball, women should not go to the games.”101 After having disparaged the women’s movement for so long, she had decided to become involved with the National Organization for Women (NOW). Her comment raised the question: was she calling for women to boycott baseball games? “Every woman should think for herself,” was all she said in reply.102

“Baseball has fought me for years,” she said. “In my heart I feel they have truly gone out of their way to hurt me because I am a woman.”103

“People have been calling me a quitter, but if I was a quitter I never would have fought it so long,” she declared. “I’m just frustrated and disappointed in baseball. My whole life has been baseball… I would have shined the ball players’ shoes if they had let me.”104

“In a way, they succeeded in getting rid of me,” she said. “But in a way, I’ve succeeded too. I’ve broken the barrier. It can be done. I don’t care what people say now. People haven’t gone through what I’ve gone through. You have to experience it to understand it.”105

WHAT CAME NEXT

Baseball may have been smug at running her out of the game, but even in the wake of Gera’s resignation from baseball there was simmering hope. The day before she became the first woman umpire in professional baseball history, Richard Nixon signed the Higher Education Amendments of 1972, which included the Title IX legislation that prohibited sex discrimination at publicly funded institutions, opening the door for more opportunities for girls and women to participate in sports.

That same weekend, the San Diego Padres had a woman manager in the dugout. Marcia Malkus was the high bidder in a charity auction, winning the chance to manage for one inning. The team scored two runs against the San Francisco Giants before she handed the team back to regular manager Don Zimmer. Zimmer confirmed that Malkus actually made all the decisions during the first inning, saying, “Women usually do.”106

Bernice Gera would likely disagree with that statement.

Two years later, in 1974, Lanny Moss was hired as the general manager of the Portland Mavericks, becoming the first woman general manager in professional baseball. Several other women were hired for the same position in her wake. Also, in 1974, lawsuits on behalf of Maria Pepe and Kim Green opened Little League Baseball to girls. In 1975, Christine Wren became the next woman to umpire in professional baseball, making her debut about three years after Gera’s game.

Wren was initially derisive of Gera, saying, “I have heard about this Bernice—I don’t know her last name and I don’t care to know. She dragged baseball through every court she could find and when she got a job she umpired one game and then quit. I feel I have a lot to overcome because of what she did.”107

However, Wren eventually hit the same wall as Gera. “In a roundabout way, it was made clear to me there was no path (to the majors),” she told the Seattle Times in 2020. “They were afraid of it. Baseball was afraid of it. They were afraid it wouldn’t look good.”108

For the men in baseball who were afraid an avalanche of women umpires would follow and feminize the sport, that hasn’t happened. After Wren, Pam Postema took a run at it. Postema spent 13 years umpiring in the minor leagues. She became the first woman to umpire a major league spring training game in 1982. In 1989, her career ended due to the time limits on umpires working without being called up to the major leagues. A handful of other women umpires followed, but only one, Ria Cortesio, made it as far as the AA level or as far as working a major league spring training game. Beating discrimination in baseball—and else-where–isn’t as easy as simply winning a court ruling.

LIFE AFTER UMPIRING

Gera always insisted that everything she did in baseball, she did to help children. Her last umpiring gig was not the painful game in Geneva. It was a charity softball game in Monticello, New York, that featured former Yankees outfielder Joe DiMaggio. It may have felt like a fitting end; she would never umpire in the major leagues, but she got to call balls and strikes for one of the all-time greats.

Her lifelong desire to work in baseball was finally fulfilled in March of 1975. The team right in her own backyard, the New York Mets, hired her for their promotion and sales department. She did community outreach work to draw people to the games.

After all those years of fighting to get into baseball, what was there to say about finally being part of a major league team? She said, simply, “It’s a dream come true.”109

She worked for the Mets for several years before her position was eliminated. She and Steve moved to Pembroke Pines, Florida. She died there in 1992 from kidney cancer at the age of 61.110

The mixed legacy she left—having broken the legal barrier on one hand but being unable to go further on the other—means her contributions are viewed with caveats. It was easy for newspaper columnists to condemn her for quitting when they were part of the system that kept her from success.

Several months after her game, Nora Ephron interviewed her for a feature in Esquire Magazine that ran in January 1973. Ephron explored the unique burdens of being the first, of being a pioneer, writing:

I cannot understand any woman’s wanting to be the first woman to do anything. … I think of the ridicule and abuse that woman will undergo, of the loneliness she will suffer if she gets the job, of the role she will assume as a freak … of the derision and smug satisfaction that will follow if she makes a mistake, or breaks down under pressure, or quits.111

Of all the perspectives and admonishments offered in the sports pages, it was Ephron who found the essential element that had been ignored in the first woman umpire in professional baseball. Breaking through the grandeur and worship we place upon our firsts, Ephron saw Gera beneath the legal battles, the symbolism, and the ugliness associated with quitting. Buried in the middle of her feature is a sentence that sums it all up: “Bernice Gera turned out to be only human, after all, which is not a luxury pioneers are allowed.”112

And as a human, all Gera wanted was to belong in baseball.

AMANDA LANE CUMMING is a long-suffering Seattle Mariners fan. To cope, she wrote for Lookout Landing for five years, where she wrote historically-focused pieces on the Mariners and local Northwest baseball. She is interested in the intersection of baseball and the broader world, particularly women in baseball and semipro and amateur teams in the early 20th century, and can often be found reading old newspapers for fun. Contact her at amandalanecumming@gmail.com or Twitter @Amanda_LaneC.

Notes

1. Debbie Blaylock, “The lady was an ump,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, August 19, 1985. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/236542667.

2. Randy Wells, “Bernice Gera, Ernest native, pro umpire, dies at 61,” Indiana Gazette, September 24, 1992. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/524426021.

3. George James, “1st woman umpire now calls all a ball,” Daily News, April 13, 1977. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/482161533.

4. Charles Clark, “Suffolk Slant,” Newsday, June 2, 1964. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/717682217.

5. “With Slugger,” Abbeville Meridional, September 19, 1961. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/445804448.

6. Sidney Fields, “Batty Over Baseball,” Daily News, August 28, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/463672946.

7. “Countrywide,” Newsday, June 9, 1964. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/712865869.

8. John Sinclair, “Woman Umpire Seeking Job,” Indiana Gazette, August 13, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/542564173.

9. Fields, “Batty Over Baseball.”

10. Ray Recchi, “Bernice Gera ‘Would Have Sold Peanuts,’” Fort Lauderdale News, April 14, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/230042389.

11. Blaylock, “The lady was an ump.”

12. “Female Ump to Officiate In National Tournament,” Wichita Eagle, July 30, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/695764585.

13. “Lady ump came-and went-a long way, baby,” Star Tribune, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/185158318.

14. Fields, “Batty Over Baseball.”

15. Will Grimsley, “Woman Enrolls In Umpire Class,” Camden News, May 19, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/31494721.

16. Red Smith, “Woman Ump Has Problem,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 15, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136573022.

17. Lance Evans, “Sports of Sorts,” The Express, June 14, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/5782706.

18. Dick West, “The Lighter Side,” The Dessert Sun, June 21, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/747505031.

19. Tommy Fitzgerald, “The Lady’s Problem As an Umpire: She Has To Keep Her Mouth Shut,” Miami News, June 10, 1967. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/301046126.

20. Fields, “Batty Over Baseball.”

21. Phil Musick, “She’s Tough,” Pittsburgh Press, June 18, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/147928111.

22. Kitty Hanson, “For Marilyn, life is a gas at Con Ed,” Daily News, July 5, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/464173292.

23. Musick, “She’s Tough.”

24. Musick, “She’s Tough.”

25. Fields, “Batty Over Baseball.”

26. Fields, “Batty Over Baseball.”

27. Musick, “She’s Tough.”

28. The umpire development program was put in place after the 1964 Winter Meetings as a way to implement a system for developing umpires in the minor leagues. Each league (majors and minors) made their own decision about which umpires to hire, but the program gave training and financial assistance to make umpiring more desirable to umpire candidates.

29. Andelman, David, “She May Change Cry to ‘Kiss the Umpire,’” Newsday, April 19, 1968. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.newspapers.com/image/716127519.

30. “Don’t Kill the Ump…It May Be Your Wife,” The News, May 1, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/533268636.

31. “Lady Ump’s Bias Claim Tossed Out,” Newsday, June 22, 1968. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.newspapers.com/image/714019777.

32. Bill Bondurant, “Baseball Threatened By Female,” Fort Lauderdale News, April 18, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/272684733.

33. “Woman Umpire!,” The Daily Reporter, April 23, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/11280962.

34. Bill Clark, “It wouldn’t work,” Montana Standard, April 25, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/354815434.

35. Bob Quincy, “Will The Lady Strike Out?,” Charlotte News, April 29, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/621252168.

36. Bill Hodge, “In This Corner,” Wichita Eagle, May 2, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/694539463.

37. David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/376643673.

38. Charles M. Guthrie, “Thumbs Down on Lady Umpires,” Star Tribune, May 5, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/185097986.

39. “Lady Umpires?,” El Paso Herald-Post, May 6, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/68505670.

40. John P. “Moon” Clark, “Moon Beams,” The Daily Republican, May 14, 1968. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/58442727.

41. “Lady Ump Charges Discrimination,” Democrat and Chronicle, March 22, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136579051.

42. Victor O. Jones, “Pats Rank 6th in TV Football Market,” Boston Globe, March 30, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/434650341.

43. Eliza McGraw, “The Kentucky Derby’s first female jockey ignored insults and boycott threats. She just wanted to ride,” Washington Post, May 4, 2019. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/05/04/kentucky-derbys-first-female-jockey-ignored-insults-boycott-threats-she-just-wanted-ride/.

44. “Today’s Sports Parade,” York Dispatch, July 28, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/615060833.

45. Division of Human Rights v. New-Pennsytvania Professional Baseball League, 36A.D.2d 364 (N.Y. App. Div. 1971). Accessed October 15, 2021: https://casetext.com/case/div-of-human-rgts-v-nypenn-baseball.

46. Jim Huber, “Miss Smokey will go to court to get chance in Indy 500,” Miami News, August 1, 1969. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.newspapers.com/image/301713562.

47. Red Smith, “Yale Reprised War of Sexes,” Democrat and Chronicle, August 1, 1969. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136644553.

48. “League president’s pitch strikes out lady umpire,” Miami News, August 1, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/301713562.

49. “Lady Ump Is Out—of a Job,” Detroit Free Press, August 1, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/98880968.

50. “League president’s pitch strikes out lady umpire,” Miami News, August 1, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/301713562.

51. “Asks Probe Of Nix on Gal Umpire,” The Post-Standard, August 2, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/10398058.

52. “Stratton Backs Gal Ump,” Democrat and Chronicle, August 5, 1069. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136645146.

53. “Congress Called In Lady Ump Case,” San Francisco Examiner, August 7, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/460208846.

54. William Vance, “Congress Goes to Bat,” Miami Herald, August 8, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/621720957.

55. Ed Levitt, “The Battle For No. 1,” Oakland Tribune, May 2, 1968. Accessed March 31, 2022: https://www.newspapers.com/image/477710726.

56. Vance, “Congress Goes to Bat.”

57. Bob Whittemore, “Did Stratton speak in haste?,” Oneonta Star, August 7, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/47364224.

58. “Congressman takes exception to column on female umpire,” Oneonta Star, August 14, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/47367050.

59. “Lady Ump Find Rough Going,” HartfordCourant, August 23, 1969. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/370538179.

60. “Pro Baseball Is Target Of Woman Umpire’s Suit,” York Daily Record, March 16, 1971. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/553356961.

61. “Mrs. Gera’s Statistics Wrong for an Umpire,” Daily News, February 12, 1971. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/463799303.

62. “Rejected Bernice Files $25 Million Suit Against Organized Baseball,” Wichita Beacon, March 15, 1971. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/694289035.

63. “Pro Baseball Is Target Of Woman Umpire’s Suit,” York Daily Record, March 16, 1971. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/553356961.

64. “Gera’s curves beating baseball,” Oneonta Star, November 23, 1971. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/47485278.

65. New York State Division of Human Rights v. New York-Pennsylvania Professional Baseball League, 29 N Y.2d 921 (1972). Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.leagle.com/decision/197295029ny2d9211555.

66. “Lady ump came—and went—a long way, baby,” Star Tribune, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/185158353.

67. “Lady ump came—and went—a long way, baby,” Star Tribune.

68. “Lady ump came—and went—a long way, baby,” Star Tribune.

69. Dave Rosenbloom, “Geneva’s Lady is an Ump at Last,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 23, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136808101.

70. Ray Recchi, “Bernice Gera ‘Would Have Sold Peanuts,’” Fort Lauderdale News, April 14, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/230042400.

71. “Now Other Umps Worrying Bernice,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, April 23, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/255587077.

72. Bill Boyle, “Bernice Gera, ‘A Little Nervous But Not Scared,’” The Daily Messenger, June 22, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/22014601.

73. “Pitching biggest problem facing biggest Oneonta Yanks,” Oneonta Star, June 21, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/51693341.

74. Boyle, “Bernice Gera, ‘A Little Nervous But Not Scared.’”

75. Boyle, “Bernice Gera, ‘A Little Nervous But Not Scared.’”

76. “Lady Umpire Preps For Debut Tonight,” The News Journal, June 23, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/163557258.

77. Dave Rosenbloom, “Bernice Says Umps ‘Where Not Cordial,’” Democrat and Chronicle, June 27, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136809359.

78. George James, “1st woman umpire now calls all a ball,” Daily News, April 13, 1977. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/482161533.

79. “Bernice: ‘I Never Got a Fair Deal,’” Press and Sun-Bulletin, June 26, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/255479134.

80. Mike McKenzie, “First Woman Umpire Wasn’t a Libber, Just a Baseball Lover,” Kansas City Times, August 2, 1979. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/677648852.

81. “I Called a Damn Good Game,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, June 29, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/255482640.

82. Dave Anderson, “’Not Worth It’ Says Lady Ump,” Intelligencer Journal, June 26, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/558038892.

83. Craig Davis, “CALLED OUT: Major League Baseball kept her out, but Bernice Gera knew her calling,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, September 15, 1989. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/237875502.

84. Davis, “CALLED OUT.”

85. Davis, “CALLED OUT.”

86. “Woman Umpire Debuts…Quits,” Pittsburgh Press, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/149367501.

87. Frank Dolson, “Noley Found He Couldn’t Win Argument With Woman Ump,” Philadelphia inquirer, June 26, 1072. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/180369547.

88. Dave Anderson, “’Not Worth it’ Says Lady Ump,” intelligencer Journal, June 26, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/558038892.

89. Dolson, “Noley Found He Couldn’t Win Argument With Woman Ump.”

90. “Lady Ump’s Career Short,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136808714.

91. Bill Boyle, “Lady Umpire Walks Off, Resigns After One Game,” The Daily Messenger, June 26, 1972. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.newspapers.com/image/22015135.

92. Guy Curtright, “Gal Ump Calls Herself Out,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136808687.

93. Dolson, “Noley Found He Couldn’t Win Argument With Woman Ump.”

94. Guy Curtright, “Gal Ump Calls Herself Out,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/136808687.

95. Curtright, “Gal Ump Calls Herself Out.”

96. Leigh Montville, “…Mrs. Gera quits in tears after debut,” Boston Globe, June 25, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/435472327.

97. “Strike one, she’s out,” The Journal News, June 28, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/162642012.

98. “The Lady Ump Lost Her Point,” Charlotte Observer, June 28, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/621958033.

99. “The umpire is out,” Star Tribune, June 28, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/185160947.

100. Vinny DiTrani, “New member of Women’s Lib,” The Record, June 29, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/493905423.

101. “I Called a Damn Good Game,” Press and Sun-Bulletin.

102. “I Called a Damn Good Game,” Press and Sun-Bulletin.

103. “Bernice Gera Joins NOW To Help Eliminate Sexism,” The News and Observer, June 29, 1072. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/652810953.

104. Vinny DiTrani, “New member of Women’s Lib,” The Record, June 29, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/493905423.

105. Dave Anderson, “’Resentment, threats’ force lady umpire to quit,” Miami News, June 26, 1072. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/301610775.

106. “Woman Manager Adds Pizzazz to Padres, but They Lose it Fast,” Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1972. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/380092191.

107. Ron Rapoport, “Behind the Plate: Christine Wren,” Los Angeles Times, January 21, 1975. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/386267885.

108. Adam Jude, “it’s not a whole new ballgame—yet—but Spokane’s Christine Wren went to bat for future generations as a professional umpire in the 1970s,” The Seattle Times, July 12, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.seattletimes.com/pacific-nw-magazine/its-not-a-whole-new-ball-gameyet-but-spokanes-christine-wren-went-to-bat-for-future-generations-as-a-professional-umpire-inthe-1970s.

109. Karol Stronger, “First Woman Ump Quit To Be A Met,” Sacramento Bee, April 10, 1975. Accessed October 15, 2021: https://www.newspapers.com/image/620636605.

110. “Bernice Gera, Umpire, 61,” The New York Times, September 25, 1992. Accessed March 30, 2022: https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/25/obituaries/bernice-gera-umpire-61.html.

111. Nora Ephron, Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women & Scribble Scribble: Notes On The Media (New York: Vintage Books, 1978), 73.

112. Ephron, Crazy Salad.