Beware of Moose: Buc No-Hits ‘69 Mets

This article was written by Bruce Markusen

This article was published in 1969 New York Mets essays

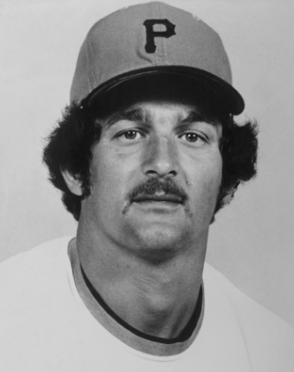

As great a season as the Mets crafted in 1969, New York’s offense sometimes struggled to score runs—or even collect hits. That was never more evident than on September 20 that season, when the Mets faced a promising young right-hander for the rival Pittsburgh Pirates. When healthy Bob Moose possessed an overpowering repertoire: a moving fastball, an effective curve, and an occasional knuckleball mixed in to throw hitters off balance.

As great a season as the Mets crafted in 1969, New York’s offense sometimes struggled to score runs—or even collect hits. That was never more evident than on September 20 that season, when the Mets faced a promising young right-hander for the rival Pittsburgh Pirates. When healthy Bob Moose possessed an overpowering repertoire: a moving fastball, an effective curve, and an occasional knuckleball mixed in to throw hitters off balance.

In 1969, Moose was in the midst of his finest season as a major leaguer. After a rough stretch in May and June, Moose had enjoyed a terrific run in July and August, pitching at first in the bullpen before earning a promotion to the starting rotation. He entered the Saturday matinee with a record of 11-3 and an ERA of 3.18, facing Mets rookie Gary Gentry. The Mets had been swept by the Pirates in a doubleheader the previous night after having lost only once over a 14-game span. Things did not get any better for the Mets at Shea Stadium on a cool Saturday afternoon against Pittsburgh’s 21-year-old right-hander.

Moose set down the first four Mets in order, all on groundouts. He experienced little trouble through the first five innings, allowing only a pair of walks, one to Ed Kranepool and the other to Ron Swoboda. Then came a watershed moment in the sixth inning. After striking out pinch hitter Jim Gosger (who was batting for Gentry) and retiring Tommie Agee on a groundout, Moose faced rookie third baseman Wayne Garrett. The left-handed hitting Garrett lofted a deep fly ball toward right field. The drive had all the earmarks of a an extra-base hit (a double at the least, and possibly a home run), but right fielder Roberto Clemente tracked the ball down before running into the Shea Stadium wall. It was vintage Clemente, allowing Moose to finish off the sixth inning with his no-hitter intact.

Energized by Clemente’s effort and uplifted by a 3-0 lead (the Pirates scored three times in the third inning on one hit, one hit batter, two walks, and two wild pitches), Moose continued sailing. He picked up two more groundouts in the seventh, though he did breathe a sigh of relief when Ken Boswell hit a line drive right at Pirates second baseman Dave Cash. Then came the eighth, when Moose forged his strongest inning. He struck out the side, fanning Swoboda, J.C. Martin, and Bud Harrelson in succession. That gave Moose six strikeouts, his final total for the afternoon.

Thanks to an insurance run in the top of the ninth inning, Moose returned to the mound with a 4-0 lead (the same score Tom Seaver took to the ninth in his “Imperfect Game” at Shea in July). He prepared to face a pinch hitter in the pitcher’s spot, followed by the top of the order, still a considerable task at hand needed to finish his masterpiece. Utilityman Rod Gaspar, called on to bat for reliever Tug McGraw, did not cooperate with Moose, drawing a leadoff walk. Having allowed his third base on balls of the afternoon, Moose then stiffened. He over-powered Agee, who popped up meekly to first base. Moose now faced Garrett, who had threatened the no-hitter with his sixth-inning drive that Clemente snagged. Pitching Garrett away, Moose induced a ground ball to third, with Richie Hebner taking the sure out at first base. That brought up Art Shamsky, one of the Mets’ toughest outs against right-handed pitching. On his way to a career-best .300 season at the plate, Shamsky managed only a ground ball to second base. Cash flipped the ball to first baseman Al Oliver to finish the game—and the no-hitter.

For the 38,784 fans who had come out on Ladies Day for the chilly Saturday matinee, they had seen history. It would also mark the last no-hitter at Shea Stadium during the final 39 seasons at the pitcher-friendly ballpark. The only other no-hitter pitched there was Jim Sunning’s perfect game during Shea’s inaugural season, the first game of a Father’s Day doubleheader with the Phillies on June 21, 1964. No Met ever pitched one at Shea Stadium or has thrown one any place else, for that matter. They are the longest tenured franchise to not have a no-hitter.

Moose’s gem, however, barely paused the Mets on their road to destiny. The Mets swept the Pirates in a doubleheader the next day—returning the favor the Pirates had done in Friday night’s twin bill—and starting a nine-game winning streak that included the NL East clincher in New York against St. Louis. The Mets did not lose again at Shea in 1969 after Moose’s no-hitter, winning the last five regular-season games there, the NLCS clincher against Atlanta, and all three games against the Orioles in the World Series to cap the Miracle.

The 1969 no-hitter also represented the pinnacle of Moose’s career. He would win his final two starts that season, sandwiched around a scoreless three-inning relief stint, to finish with a record of 14-3 and an ERA of 2.91. His .824 winning percentage led the league—43 points ahead of runner-up Seaver.

Seemingly born to be a Pirate, Robert Ralph Moose Jr. grew up just 15 miles from Forbes Field, throwing six no-hitters in high school and American Legion ball. He was drafted by his hometown club in the 18th round of the first major league draft in 1965 and made his pro debut in 1965 at age 17 with a 1.95 ERA that summer in Salem, Virginia. He moved right up the ladder and debuted while still a teen in 1967. While Moose possessed a live repertoire when healthy, he made more of an impression on his teammates with his workmanlike approach. The gritty pitching style of Moose, who never shied from taking the ball—either as a starter or a reliever—drew the admiration of other Pirates pitchers. “Bob came from the old school and was a hard worker,” says former Pirates closer Dave Giusti, who played with Moose in Pittsburgh from 1970 until 1976. “When he had a sore arm, you’d never know it, because he still wanted to go out there and pitch.”

Moose’s willingness to pitch through pain might have cost him. Plagued by arm troubles in his later years with the Pirates, Moose’s effectiveness fell into quick decline. He matched his 1969 ERA (2.91) while going 13-10 in 1972, but the everlasting image of him that year was his wild pitch in Cincinnati that ended the NLCS. After struggling through a 1-5 season in 1974 Moose evened his record at 2-2 the next year. After going 3-9 and lowering his ERA for the third straigh year in 1976, Moose’s life would end suddenly. He died in a car accident on October 9, just a few days after the conclusion of the 1976 regular season. Moose perished on the day of his 29th birthday.

Giusti remembers hearing the news of Moose’s passing. “In fact, we were down at Bill Mazeroski’s golf tournament,” says Giusti. “It was myself and [Pirates pitcher Jim] Rooker, and a few other guys on the ballclub who were down there. Yeah, I remember that. In fact, I got a call from Rooker. He had found out that Bob Moose was in an accident, so we went down and identified the body. It was an awful time.”

Though still a young man, Moose had left a defined impression with the Pirates teammates. “He was a nice guy to be around,” Giusti says. “He was kind of a maverick, too. He would be one of those guys that would start some stuff in the clubhouse, also. He had the Afro-type hairdo, and he would curl it, just to get on Dock Ellis’s case. He’d try to find ways to get under people’s skins, also.”

For one day in 1969, Bob Moose found a way to imbed himself deeply in the skins of the eventual world champion Mets.

BRUCE MARKUSEN is the author of seven books on baseball, including the award-winning A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, the recipient of the Seymour Medal from the Society for American Baseball Research. He has also written The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates, Tales From The Mets Dugout, and The Orlando Cepeda Story. He currently works as a museum teacher at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Farmers’ Museum, and the Fenimore Art Museum, all located in Cooperstown, New York. In addition to writing for The Hardball Times website, he also contributes articles to Bronx Banter. Bruce, his wife Sue, and their daughter Madeline reside in Cooperstown.