Big League Cheating

This article was written by Mark Halfon

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

Editor’s note: This article was published in the April 2018 edition of the SABR Deadball Era Committee newsletter.

Pervasive cheating plagued baseball during the Deadball Era. Cutting bases, blocking baserunners, doctored baseballs, lob pitches, indifferent play, bribery, and fixed games found a way into every crevice of baseball. Much of the indiscretion occurred openly, regarded as “part of the game” and caused little concern, but egregious unchecked violations of baseball law threatened the very integrity of the sport. The National Commission led by Byron Bancroft “Ban” Johnson governed the national pastime but routinely ignored, covered up, and whitewashed actions that pushed the limits of honest baseball. The powers-that-be faithfully protected baseball’s image at the expense of sanctioning a culture in which dishonesty flourished.

Jack Taylor’s performance in the 1903 Chicago City Series provided an early opportunity for baseball’s overseers to address corruption. The Chicago Cubs ace tossed a shutout in the opener followed by 10-2, 9-3, and 4-2 thrashings by the weak-hitting White Sox. Suspicious of treachery but absent any proof, Cubs president James Hart traded his star pitcher to the St. Louis Cardinals. The following season, though, compelling evidence of Taylor’s guilt surfaced, and it came from his own mouth. After Cubs fans taunted him in his return to Chicago, he responded, “Why should I have won? I got $100 from Hart for winning and I got $500 for losing.”1 It sounded like a confession and Hart aired his concern, but no investigation of Taylor followed.

Jack Taylor’s performance in the 1903 Chicago City Series provided an early opportunity for baseball’s overseers to address corruption. The Chicago Cubs ace tossed a shutout in the opener followed by 10-2, 9-3, and 4-2 thrashings by the weak-hitting White Sox. Suspicious of treachery but absent any proof, Cubs president James Hart traded his star pitcher to the St. Louis Cardinals. The following season, though, compelling evidence of Taylor’s guilt surfaced, and it came from his own mouth. After Cubs fans taunted him in his return to Chicago, he responded, “Why should I have won? I got $100 from Hart for winning and I got $500 for losing.”1 It sounded like a confession and Hart aired his concern, but no investigation of Taylor followed.

Taylor predictably continued his shenanigans in St. Louis where teammates accused him of throwing the contest of July 30, 1904 against the Pittsburgh Pirates. The National League Board of Directors called a hearing in which Taylor claimed that drinking and gambling the night before the contest, rather than misconduct, caused his poor performance. That was good enough for the Board. On February 13, 1905, it acquitted Taylor of throwing the game but found him guilty of “misbehavior” and fined him $300, which he refused to pay.

One month later the National Commission finally investigated Taylor’s performance in the 1903 City Series. Cubs president Hart submitted affidavits from fans attesting to the pitcher’s incriminating admission, but on March 17 the Commission ruled that Taylor might have been joking and exonerated him of all charges. Taylor had to be emboldened and later that season Cardinals teammates accused him of throwing two games in the St. Louis City Series. Neither the National Commission nor National League Board of Directors took action. The stage had been set for what would become a troubling pattern over the next two decades.

Baseball officials had an opportunity to condemn brazen corruption in the stretch run for the 1908 National League pennant race. On September 23, New York Giants rookie Fred “Bonehead” Merkle’s failure to touch second base turned an apparent win into a tie against the hated Cubs. Giants Manager John McGraw fumed at the perceived injustice and sought redress in his club’s eleven remaining games, eight against the Philadelphia Phillies and three against the Boston Doves. New York would have swept Philadelphia if not for three victories by rookie left-hander Harry Coveleski, but did sweep Boston, resulting in a deadlock between the Giants and Cubs atop the National League standings. A replay of the September 23rd contest would decide the championship. Prior to the start of the game, New York team physician Joseph “Doc” Creamer offered umpires Bill Klem and Jim Johnstone an envelope containing $5,000 if they ensured that close calls went the way of the Giants. The umpires refused and Chicago defeated New York 4-2 to win the pennant and later the World Series, but much had been happening behind the scenes.

One day after the Cubs victory, Phillies manager Billy Murray accused McGraw of attempting to bribe two of his pitchers while Doves manager Joe Kelley claimed McGraw bribed one of his outfielders and his shortstop. One headline read: “National League Facing Scandal: Managers of Philadelphia and Boston Clubs Openly Charge McGraw with Attempting to Bribe Players to Throw Games in Two Final Series and Demand Investigation by the Board in Control.”2 The National League Board of Directors thought otherwise. Testimony from two major league managers regarding games that impacted a championship garnered no interest from this board.

Umpires Klem and Johnstone then reported Creamer to National League President Harry Pulliam, who formed a committee to investigate the alleged bribe. But in a move that betrayed utter contempt for impartiality, Pulliam selected Giants owner and McGraw friend John T. Brush to head the investigation. Without identifying him, Brush’s committee banned Creamer from all major league parks for life and never questioned McGraw.

National League authorities cemented a reputation for cunning, but baseball executive extraordinaire, founder of the American League, and charter member of the Hall of Fame Byron Bancroft “Ban” Johnson stood out as the master of deception. Johnson’s role in the battle between Ty Cobb and Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie for the 1910 batting title revealed a willingness to cover-up what may have been baseball’s most blatant exhibition of cheating. Cobb had a seemingly insurmountable lead heading into the final day of the season, but a doubleheader remained between Lajoie’s Cleveland Naps and the St. Louis Browns. In his first at-bat, Lajoie hit a routine fly that center fielder Hub Northern “misplayed” for a triple. The Naps power hitter next legged out a grounder hit toward deeply-positioned shortstop Bobby Wallace for a single. In his final seven at-bats, Lajoie bunted toward rookie third baseman Red Corriden, who had moved to the edge of the grass in short leftfield. Much to the dismay of Browns coach Harry Howell, official scorer E. Victor Parrish ruled one of Lajoie’s bunts a sacrifice, with Lajoie taking first on a Corriden fielding error, rather than a hit. So, Howell sent the Browns batboy with a note to Parrish offering him a $40 suit if he changed his ruling from a sacrifice to a base-hit. Parrish refused, and Lajoie ended the day 8-for-8, with a sacrifice.

What happened that day sparked outrage around the country. “All St. Louis is up in arms over the deplorable spectacle” raged the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.3 Never before in the history of baseball has the integrity of the game been questioned as it was by 8,000 fans this afternoon” fumed the Washington Post.4 “It was the most farcical and unsportsmanlike exhibition ever recorded in the history of the sport” wrote the Oakland Tribune.5 Johnson summoned Corriden and Browns manager Jack O’Connor to get their version of what occurred. Corriden said that he followed O’Conner’s instructions and did not want to get killed playing in close on Lajoie. All indications are that Corriden played his normal position in the team’s four prior meetings but Johnson never asked. Instead, he praised Corriden’s honesty and cleared him of misbehavior. The American League president then cancelled his meeting with mastermind O’Conner, who he said would testify “that there was no intentional wrongdoing.”6 Corriden’s claim that O’Conner told him to play an extremely deep third base appeared deserving of inquiry, but not to Johnson.

Baseball’s czar soon had another chance to probe the batting controversy after official scorer Parrish reported that the bribery attempt he received could “be substantiated by three gentlemen, the integrity of whom cannot be questioned.”7 Johnson never questioned Parrish or the gentlemen. Doing so would have exposed baseball’s underbelly.

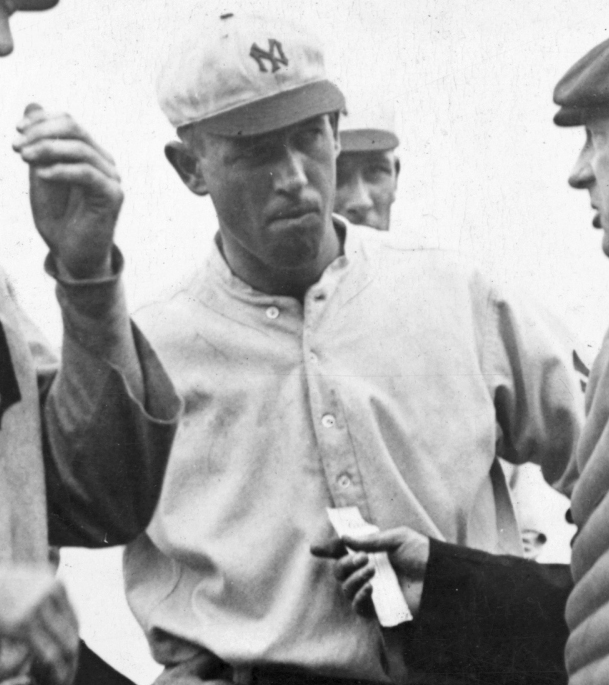

That same season, Johnson’s treatment of Hal “The Black Prince” Chase further confirmed his skill at subterfuge. After Highlanders manager George Stallings accused Chase of fixing games, Johnson instructed club owners Frank Farrell and William Devery to fire Stallings and hire Chase, proclaiming, “Anybody who knows Hal Chase knows that he is not guilty of the accusations made against him.”8 Baseball’s dirtiest player had the protection of baseball’s most powerful figure.

That same season, Johnson’s treatment of Hal “The Black Prince” Chase further confirmed his skill at subterfuge. After Highlanders manager George Stallings accused Chase of fixing games, Johnson instructed club owners Frank Farrell and William Devery to fire Stallings and hire Chase, proclaiming, “Anybody who knows Hal Chase knows that he is not guilty of the accusations made against him.”8 Baseball’s dirtiest player had the protection of baseball’s most powerful figure.

Chase continued down a wayward path over the next decade but faced a formidable opponent in 1918 when playing for Cincinnati Reds manager Christy “The Christian Gentleman” Mathewson, who suspended Chase after teammates reported he offered them bribes to throw games. National League president John Heydler held a hearing on January 30, 1919 in which Reds pitchers Jimmy Ring and Mike Regan, and outfielder Greasy Neale testified against Chase, while Mathewson, still overseas on WWI military duty, supplied an affidavit. The evidence appeared overwhelming, but Heydler dismissed all charges, saying, “Chase did not take baseball or anything else seriously, and many of the things he says in joking spirit are construed otherwise.”9 Mathewson complained of a cover-up but had no recourse. Chase, meanwhile, remained unscathed during the 1919 season. Eddie Cicotte and company had to have taken notice.

Perhaps the defining moment in Johnson’s tenure came during the 1919 World Series. Prior to Game Three, White Sox manager Kid Gleason informed owner Charles Comiskey that his club may have thrown the first two games of the Series. Comiskey no longer spoke with former friend Johnson but had Heydler relay his concerns to the American League president, which Johnson dismissed as accusations of a “beaten cur.” Baseball’s czar once again had a chance to place honor above profit but remained in character to the detriment of the good name of baseball.

MARK S. HALFON is a professor of philosophy at Nassau Community College in New York and the author of “Tales from the Deadball Era: Ty Cobb, Home Run Baker, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and the Wildest Times in Baseball History” (Potomac Books, 2014).

Notes

1 Donald Dewey and Nick Acocella, The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game (Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2004), 28.

2 Anaconda (Montana) Standard, October 13, 1908.

3 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1910.

4 Washington Post, October 10, 1910,

5 Oakland Tribune, October 10, 1910.

6 Boston Globe, October 15, 1910.

7 Boston Globe, October 13, 1910.

8 Harold Seymour (and Dorothy Seymour Mills), Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 289.

9 New York Times, February 6, 1919.