Black Cats, Blue Suits, and Orange Socks: How Earl Weaver’s Orioles Thrived on Superstition

This article was written by Dan VanDeMortel

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

Meooowwwwww, avoid black cats! Don’t step on the base lines! Don your rally cap! Grab your magic seat and jewelry!

Superstition has been a part of baseball since the game’s earliest days. Almost anything and anyone have been fair game to promote personal and team good fortune: pre-game meal rituals, lucky clothes and equipment, mascots, dwarves, albinos, hunchbacks, peculiar avoidances, cherished habits, spiritual Hail Marys, even voodoo.

It’s impossible to quantify baseball’s all-time most superstitious team, but Earl Weaver’s Baltimore Orioles during his 17-year managerial career (1968–82, 1985–86) would be a good candidate for the title. Plus, modern research indicates it may even have even contributed to the team’s success.

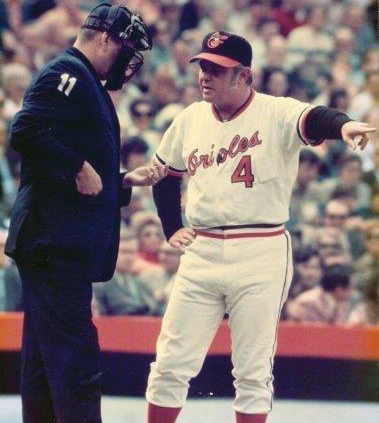

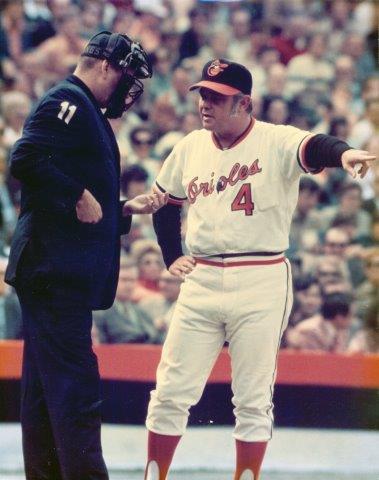

From afar, a Weaver clubhouse seems an improbable place for superstition. Outwardly, the 5-foot-7 combative field general came across as a no-nonsense fire plug, more likely to argue with players and umpires than touch wood. Weaver was a highly rational baseball man who relied on statistical research, platoons, walks, and the three-run home run in a time when analytics was confined to a few “traditional” statisticians, computer nerds, and a young Bill James toiling in the wilderness.1 Weaver’s intense focus yielded impeccable results: a .583 winning percentage, four American League pennants, and a 1970 World Series championship. The team obviously bought into Weaver’s approach. But underneath that rational veneer lay enough superstitious behavior to fill 12 or 14 (not “13,” please) psychology notebooks.

Orioles manager Earl Weaver was known for his combative nature with umpires, once being tossed twice in one day during a 1976 doubleheader.

Let’s start with the boss. Weaver was a two-pack-a-day cigarette smoker who lit up proudly and often in the dugout, sometimes while televised, rationalizing his addiction through his insistence that the opposition scored every time he failed to smoke between innings.2 In the Memorial Stadium dugout, he rested his foot against a “good-luck” pole and ordered anyone nearby to stay away. When the Orioles were winning, he avoided looking at a clock. He used the same red pen until the team lost, then switched to another color in hopes one would propel new success. According to Orioles’ public address announcer Rex Barney, Weaver would even become violent if his pen ran out of ink during a winning streak.3 And during some hot streaks that occurred while Weaver was “on vacation” — serving suspensions for unpleasant interactions with umpires — upon his reinstatement he would either refuse to sit on the Orioles’ bench or simply let a coach manage until the winning stopped.

Under Weaver’s penchant for good luck charms and fortune-inducing habits, his ballplayers followed suit, often surpassing the master with their individual and collective oddities. During one successful 1974 stretch, slick-fielding shortstop Mark Belanger traced an “S” route on and off the field each inning, faithfully circling outside the third-base coach’s box, then veering between the coach’s rectangle and bag en route to his position, then reversing course for the Orioles’ turn at bat. That same year, pitching ace Jim Palmer made sure to sit in his “defensive seat” on top of the back rest to the left of pitching coach George Bamberger and next to the bat rack when the Orioles were on offense. Bamberger, meanwhile, during a stretch of six consecutive victories and 10 out of 11, hit the bench three times with a bat during each inning. And when a rally was needed, infielder Enos Cabell batted the water cooler repeatedly, sometimes assisted by outfielder Al “The Bumblebee” Bumbry and infielder Tim Nordbrook. Weaver, favoring superstition over discipline, made no effort to interfere, observing, “It’s noisy, but we like it.”4

Pitcher Pat Dobson’s 1971 behavior was equally strange. While readying for his June 8 start, he discovered his socks were missing from his locker. Noticing that pitcher Mike Cuellar’s locker contained an extra pair of orange socks, Dobson nabbed them and pulled them on while immersed in a 45-minute discussion with Baltimore News-American writer Chan Keith. Once their topics and his feet were covered, Dobson went on to beat the Twins 8–2. During his next start, he became involved in another long chat with Keith “about the price of automobiles, the headaches of sports writing, [an] athlete’s responsibilities to the public,” and, perhaps, baseball.5 This time, Dobson was clubbed 7–3 by the White Sox. Talking with Keith, obviously, was not the good luck charm, right? Wrong. The problem, Dobson deduced, was that he had not worn Cuellar’s “magic” socks. For his next several starts, Dobson wore the same pair of Cuellar’s socks and sought out Keith for his conversational “fix,” even waiting once until the last minute in Oakland when Keith’s arrival was delayed. As the wins mounted on the way to 20 victories, Dobson quipped Keith would receive one percent of any offseason salary increase: just a bit short of Keith’s jocular counterproposal of 20 percent.

A black cat probably did not cross Dobson’s path during this successful stretch, but one did encounter outfielder Rich Coggins during winter ball in Puerto Rico. One season while Coggins was mired in a slump and personal problems, a black cat walked in front of his car several days in a row. “Before that, I was never superstitious about black cats. Then I started entertaining that superstition and letting it bother me,” Coggins admitted.6 Later while Coggins was arriving at a Burger King, a black cat came to rest in front of his car. Exiting the car and slowly approaching the cat, Coggins asked, “Why are you on me?” The cat stayed put and stared at him. Coggins spoke to it some more, then walked away, as did the cat. “I realized as I talked to it both good and evil are around and that you have to deal with them. It became a challenge to overcome my problems rather than sulking. Now I understand black cats,” Coggins concluded.7

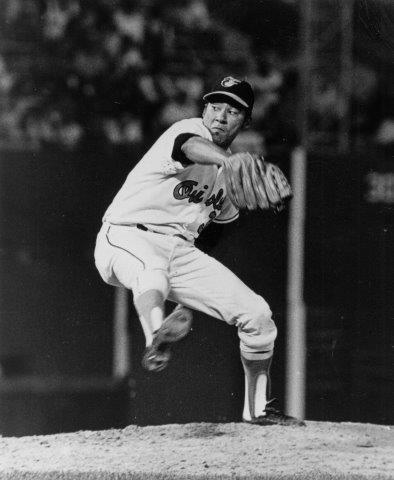

Coggins’ el gato negro, however, would have needed a Gatorade bucket of catnip to imagine the Orioles most superstitious player of all time, perhaps baseball’s, too: Mike Cuellar. The Cuban screwball-tossing lefty’s oddball rituals and quirks earned him the nickname “Crazy Horse” for good reason. No black cats were involved, but his “action verb” theatrical resume was and is legendary, confusing, and amusing, including:

- Flying in a blue suit while wearing a special gold-chain medallion.

- Believing in the spirit of his magic baseball cap, which he wore when he pitched. Once while on the road in Milwaukee, he insisted the Orioles fly the forgotten cap to him. Noticing upon arrival that it was only his practice hat, Cuellar refused to pitch.

- Eating Chinese food the night before he pitched.

- Taking batting practice on start days, even after the designated hitter rule took effect.

- Smoking a cigarette per inning in the runway off the dugout or in the same seat on start days.

- Sitting on the “lucky” end of the training table before taking the field, receiving an arm massage with his medallion safely draped around his neck.

- Allowing only select catchers and coaches to receive his warm-up pitches and simulate a batter.8 Never finishing warm up tosses until the opposing starter completed his.

- insisting that upon completing warm-ups the ball be thrown to a specifically designated person in the dugout (usually Jim Palmer, though an alternate receiver could be designated)9

- Observing a strict mound entrance behavior code. Waiting for his teammates, including his gear-donning regular catcher, to take the field while requiring one of them to place the ball on the mound (do not toss it to him!). Hopping carefully over the top dugout step, walking purposefully, avoiding contact with the baseline, proceeding to the front of the mound, waiting for someone to kick the resin bag to the back of it, then ascending at an angle from which the batter could not see his face.

- Departing the mound per a similar code: Retracing his path to the dugout, avoiding the baseline, and making a precise number of steps to the water cooler.

- Retrieving his glove if an inning ended while at bat or on the bases. Always carrying his glove to the mound and never allowing anyone to hand it to him.

Whew. Wait, there’s more. In 1972 Indians outfielder Alex Johnson tried to disrupt this rhythm by carrying his third inning-ending caught ball to the infield, timing his arrival with Cuellar’s. When Johnson tossed the ball to him, Cuellar ducked and the ball rolled free. Subsequently, the bat boy, first baseman Boog Powell, and the umpire all unsuccessfully attempted to throw the ball to a dodging Cuellar. Only after second baseman Bobby Grich rolled it to the mound did Cuellar finally pick it up. Just to turn the screw a little tighter, Johnson tried the same trick in the fourth. Cuellar, however, would not take the bait, waiting in the dugout for Johnson to flip the ball to Powell, who then rolled it to the mound. With order restored, Cuellar then followed his usual mound entrance checklist.10

Miguel Angel “Mike” Cuellar won 20 games four times for the Orioles. Perhaps all his superstitions worked.

Amidst this surreal team pursuit of favorable intervention, Jim Palmer asked, “We all know that superstitions aren’t winning ballgames for us. But who wants to find out?” Well, some researchers do, and it turns out Palmer is wrong on superstition’s ability to influence events.11

University of San Francisco anthropology professor George Gmelch has been studying baseball superstition for decades. Considering the game’s three essential activities of pitching, hitting, and fielding, he’s found that chance plays an important role in the first two. In particular, the pitcher is the player least able to control events, given his reliance upon his own skill plus the abilities of his teammates, the skill or ineptitude of the opposition, and luck. Hitting likewise offers uncertainty due to its low success rate and chance’s role in sometimes determining whether a batted ball will be caught or just barely elude an outstretched glove.

Gmelch has identified three types of magical behavior players use to combat these uncertainties. The most common one is to develop and adhere to a regularly followed daily routine, bringing comfort, order, and concentration into a world which offers challenge and randomness. Some players extend this further by engaging in rituals — such as Orioles players banging on objects — to bring luck to their side. These rituals grow out of successful performances, the repetition of which is used to gain control over future uncertainties. Second, some players adopt taboos, mostly idiosyncratic behavior — such as avoiding stepping on foul lines — that is used to avoid bad luck. Lastly, players resort to fetishes such as special clothing, coins, jewelry, gloves, and the like that coincide with lucky streaks or provide some sort of supernatural ability to create them. Individually or collectively, these behaviors combine to give players confidence and a dose of security.12

Other experts concur. Vrije Universiteit (VU) Amsterdam professor Dr. Paul van Lange finds that these practices help people including athletes cope with unknown outcomes, especially individuals who perceive and externalize events as subject to chance and unpredictability and in situations where the stakes are high and the opponent is formidable.13 And in a 2010 breakthrough study, University of Cologne (Germany) researchers’ experiments found that belief in luck can improve performance at a skilled activity when luck-enhancing superstitions produce psychological benefits that translate to better performance on the field.14

These findings illuminate a “crazy” player such as Cuellar, who, like many Latin players of his generation, was often ignored by sportswriters or quoted in “pidgin English.” Cuellar was a private person, a man who was uncomfortable talking about personal matters and who had not seen his parents for many years after leaving Cuba to play baseball in the US. Who wouldn’t turn to superstition if given that same kind of precarious psychological, emotional, and geographical lifeline? As for other players with more average, untroubled backgrounds, they faced and still face prospective slumps, doubts, demotions, trades, salary negotiations, fan abuse, press attacks, and injuries on a daily basis. Nowadays, they face social media dissection, too. When dealt that hand, the line between superstitious belief and desired salvation is thin, indeed.

DAN VANDeMORTEL became a Giants fan in upstate New York and moved to San Francisco to follow the team more closely. He has written extensively on Northern Ireland political and legal affairs. His baseball writing has appeared in “The National Pastime,” San Francisco’s “Nob Hill Gazette,” and other publications. His article “White Circles Drawn In Crayon” won the 2020 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award. Feedback is welcome at giants1971@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

A knock on wood goes out toward Professor George Gmelch and Ken Manyin for their assistance with this article.

Sources

Photo: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Notes

1 Umpires ejected Weaver 97 times, placing him fourth on the all-time list.

2 Weaver’s nickname for Orioles relief pitcher Don Stanhouse was “Full Pack.” Weaver claimed he went through a full pack of cigarettes while Stanhouse pitched. See “Don Stanhouse,” Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Don_Stanhouse.

3 Ira Berkow, “Players; Weaver Keeps Whirring,” New York Times, September 23, 1982.

4 Lou Hatter, “Birds Beat Water Cooler, Bench As Well As Foes,” Baltimore Sun, October 1, 1974.

5 Lou Hatter, “Dobson Adheres To Pat Pattern,” Baltimore Sun, August 2, 1971.

6 Phil Hersch, “Will The ‘Twin’ Image Hurt Al Bumbry and Rich Coggins?,” Baltimore Sun, October 7, 1973.

7 As for the cat, it likely sauntered away to a nearby food bowl to ponder cosmology, followed by a nap. If Coggins knew the background behind black cats and luck, he might have held a more nuanced view of his furry visitor. Throughout history and in some countries black cats have sometimes been a sign of good luck or fortune. But, in the Middle Ages, they became linked with witches, which led to their origin of distrust in America where they became associated with the Devil and witchcraft. Supposedly, having one cross your path means you have been noticed by the Devil. All a bit humorous until you consider that black cats are adopted at shelters less than other cats, partly because of negative superstitious beliefs.

8 Dobson and Palmer also adhered to this ritual.

9 Hatter, “Birds Beat Water Cooler, Bench As Well As Foes.”

10 Johnson was a talented but troubled player. Although his interaction with Cuellar was in jest, he suffered from mental health issues that contributed to a career of tempestuous relationships with opponents, teammates, coaches, management, and sportswriters.

11 Hatter, “Birds Beat Water Cooler, Bench As Well As Foes.” .

12 George Gmelch, “Baseball Magic,” Human Nature, Vol. 1, No. 8, 1978, https://meissinger.com/uploads/3/4/9/1/34919185/gmelch_baseball_magic.pdf; Gmelch, George, Inside Pitch (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 133-143; George Gmelch, email, February 24, 2020.

13 Paul Van Lange, “The Psychological Benefits of Superstitious Rituals In Top Sport: A Study Among Sportspersons,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology (Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing, Inc., 2006), 2532-2553.

14 Stuart Vyse, Believing In Magic: The Psychology of Superstition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), xi, 232-33.