Boodle and Barnstorming: When Politics and the National Pastime Convened in Dwight, Illinois

This article was written by Bill Pearch

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

Col. Frank Leslie Smith (1867-1950) was a banker, real estate dealer, congressman, and baseball fan. A slender, self-made man, Smith adhered to a simple doctrine that empowered his rise from humble roots into the political sphere: the end justifies the means.1 This motto helped forge formidable business connections and amass political clout on local, regional, and national stages. Smith also used any means necessary to construct a winning team for Dwight, Illinois, a strategy that paralleled his rise to national prominence and his ultimate downfall.

While Smith lacked talent to play professional ball, he gained status within the Illinois Republican party and weaved the game into his lifelong pursuit of elected office. Despite repeated efforts to secure office, he only made it to Congress twice. He claimed to stand “for the honest conduct of political office and public trust.”2 But when Smith died in 1950, the Chicago Sun-Times mentioned his scandalous pursuits of a US Senate seat, acknowledging defeat “by only 11,000 votes,” and ultimately, being “beaten by $285,000.”3

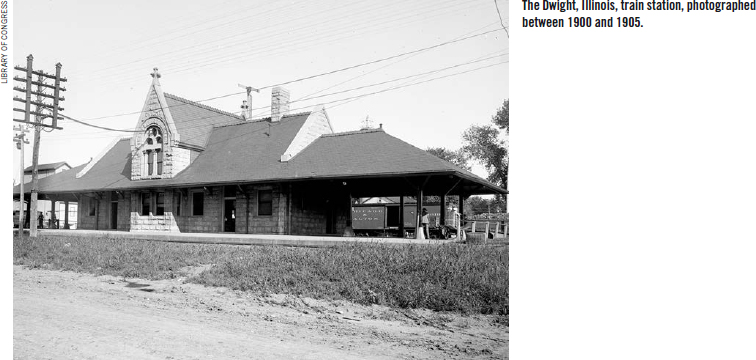

The town of Dwight today remains best known as the former headquarters of the Keeley Institute and its unorthodox alcoholism treatments. At the time of Col. Smith’s birth there, approximately 70 miles southwest of Chicago, Dwight was a community of about a thousand residents. Rockford’s Register-Gazette suggested in 1892 that Dwight was a first-class community devoid of any amusement, making it ideal for a minor league team in the Illinois-Iowa League.4

Dwight’s earliest documented baseball reference appeared in June 1868, when Willie Gardner, captain of the Pony Club of Dwight, challenged “any Base Ball Club in the City of Wilmington which has no member over 14 years of age” to a game.5 Later that summer, a scathing editorial shamed locals and asked, “What has become of the Base Ballists?” and questioned their desire “for allowing other towns of less magnitude to excel in the national game.”6 No local ordinances prohibited baseball, so perhaps “the young men are either too lazy or do not wish to run the risk of having broken fingers.”7 Perhaps the editorial prompted the 1871 formation of the Dwight Renfrews, named after Lord Renfrew, the Prince of Wales’ alias used during a local hunting expedition in 1860.8

While details of Smith’s childhood remain sparse, baseball proved formative. Smith was known locally as an expert ballplayer “playing just about as good ball as anyone” and “making good stops and placed the ball well when batting.”9,10,11 Many of the traits that defined his professional career—aggressiveness and a will to dominate—manifested themselves during juvenile sandlot games.12

Smith was likely too young to witness one of Dwight’s earliest organized games against Broughton Township in June 1871, but perhaps an 1874 military display sparked his passion.13,14 Prior to a game between the Renfrews and Pontiac Athletics, a steam engine exploded and injured several onlookers. Simultaneously a gentleman named Slane Turner suffered arm injuries when a cannon prematurely fired. Explosions aside, nearly 3,000 people watched Dwight win, 20-13.15

Smith’s rise to political prominence began in 1895 when he became the junior partner at Romberger & Smith, a real estate and private banking firm.16 After hours, he managed the firm’s semiprofessional baseball team—the Dwight R&S, named after his partner and himself.

Smith organized schedules against town teams and semipros from neighboring locales. He demonstrated a knack for securing elite homegrown talent and distinguished newcomers. Most of Smith’s players never advanced beyond the semiprofessional level, but several local players—Burt Keeley, George Cutshaw, and Bud Clancy—donned local jerseys before jumping to the majors. The roster included one Dwight native, Eddie Higgins, who briefly pitched for the St. Louis Cardinals. Smith even signed major league stars for short stints, including “Turkey” Mike Donlin and Bill Sherdel.

As Smith’s team gained notoriety for playing fast and dynamic games, he opted to test their mettle—and simultaneously shine a light on his burgeoning political aspirations—by attracting barnstormers and novelty acts to Dwight. He also arranged a handful of games against American, National, and Federal League teams on his home field.

One thousand fans traveled to Dwight on August 27, 1901, to witness the community’s most significant baseball game to date.17 Smith organized a contest against the traveling Nebraska Indians and granted Dr. Herbert Lehr—a recent transplant and University of Michigan three-sport star18—pitching honors. The Dwight R&S plated four runs in the bottom of the first inning as Lehr was unhittable until the third when the floodgates opened. The game ended in 16-6 onslaught in favor of the barnstormers. Despite the final score, Smith had established a standard for competition and a vehicle for self-promotion.19

In 1902, Smith gained control of his partner’s portion of the firm.20 With new business arrangements, he rebranded both the firm and baseball team. The Dwight R&S became the Frank L. Smiths.21

During the ensuing years, Smith’s political aspirations grew as did the quality of his team’s competition. He suffered an unsuccessful run for Illinois lieutenant governor opening in 1904, as the Smiths began challenging teams from Chicago’s semipro circuit and several Black baseball teams at Dwight’s West Side Park.22

Captivated by the Chicago-centric 1906 World Series, Smith aimed higher when he organized his team’s schedule in 1907. In June, the Smiths hosted the Cuban Stars of Havana. Jimmie Brown, the hometown pitcher, allowed two first-inning runs and received no offensive support. The barnstormers blanked the Smiths, 2-0.23

In late July, Seattle High School’s team descended upon Dwight promoting the upcoming Alaska-Yukon- Pacific Exhibition. The Smiths “lacked the fast, snappy work that won so many games” earlier that year.24 That afternoon, 16-year-old Charlie Schmutz—a future Brooklyn Robins pitcher25—stymied the local squad and the Seattleites won, 6-5.26

In mid-September of that year, Mabel Hite, eccentric ballplayer Mike Donlin’s wife, revealed the secret of her husband’s inexplicable disappearance. The actress and comedian shared that he was a patient at Dwight’s Keeley Institute receiving the so-called “Keeley cure” under an assumed name.27 Donlin opted for the vaudeville circuit with his wife following a preseason contract dispute with the New York Giants. He even played for Jimmy Callahan’s Chicago semipros, the Logan Squares.28 Ever the opportunist, Smith enlisted Donlin’s services for a significant engagement.

Smith and Callahan coordinated to bring one of the two pennant-winning teams to West Side Park. They arranged for the American League’s pennant-winning Detroit Tigers to challenge the Smiths in Dwight on Tuesday, October 22.29

The Tigers arrived via train and were warmly greeted by a throng of local baseball fans.30 Businesses were encouraged to close shop that afternoon and happily obliged.31 More than 1,500 fans flooded the ballpark as the Tigers thumped the Smiths, 8-1.32

The game remained scoreless until the fourth inning, when Ty Cobb reached first safely on a Donlin error. Cobb stole second base, then scored on Claude Rossman’s single. The Tigers padded their lead with single runs in the fifth and sixth.33 Detroit sealed the Smiths’ fate with a four-run eighth and an insurance run in the ninth, winning 8-1.

The umpires cut the Smiths some slack. During one at-bat, Donlin singled to right field. Cobb, aware that Donlin loafed toward first base, fielded and fired the ball to Rossman and beat the runner. When the umpire ruled Donlin safe, Cobb erupted into hysterics at the blatant hometown favoritism, unable to contain his laughter.34

Higgins, the 19-year-old local starting pitcher, limited the Tigers to nine hits, and perhaps with stronger defense, the result would have been closer. Dwight’s defense committed five errors that afternoon. For good measure, Smith played shortstop and recorded four assists and one putout. He reached base on a ninthinning fielder’s choice, but the game ended when he interfered with Donlin’s groundball toward first.35

Three-I League scouts were impressed and signed Higgins and George Cutshaw to the Bloomington (Illinois) Bloomers squad. Higgins joined the Cardinals in 1909 and played 18 total major-league games. Cutshaw enjoyed a 12-year major-league career with Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, and Detroit, playing second base for the Brooklyn Robins in all five games of the 1916 World Series.

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Smith as internal revenue collector in Illinois’ Springfield district.36 That role proved beneficial and strengthened his connection with William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s handpicked presidential successor.37 As Smith’s political ambitions strengthened, his passion for bringing baseball attractions to Dwight increased. On October 15, 1908, a hodgepodge of players identified as the American League’s Washington Senators arrived in town. Initial promotions billed a pitching duel between Eddie Higgins, now a member of the Bloomers, and Walter Johnson.38 Few actual major leaguers played with the remainder of the lineup selected from Chicago’s amateur ranks at the last moment.39 The Smiths jumped on Burt Keeley, a former Dwight R&S pitcher with no relationship to the Keeley Institute, but Washington managed to win, 4-3.40

As 1910 waned, Giants manager John McGraw received word that Arthur “Bugs” Raymond would curtail his drinking by entering Dwight’s Keeley Institute.41The Times (Streator, Illinois) noted that Smith’s players should gain some sage pitching insight from the National League hurler, but whether he tutored any Smiths is unknown.42 The Keeley Institute expelled Raymond quickly due to excessive horseplay.43

Though a competitive squad with a winning record, the Smiths’ talent waned for several seasons. In 1911, Col. Smith’s team traveled north to Dellwood Park—a lavish park constructed by the Chicago and Joliet Electric Railway to encourage ridership—for a series of games against the Joliet Standards in July and August.44 Typically known for top-notch quality of play, the Smiths’ decline was memorialized by The Joliet News after their 11-10 win on July 30, calling it “a slow game crowded with many stupid, asinine plays, faulty work and rotten judgment.”45

The Smiths’ performance regressed and wrapped the 1912 season with a 14-12 record, but concluded play with a contest against the Chicago Cubs on October 24.46 The Cubs trotted out their regulars, except for Johnny Evers who remained in Chicago.47 That same day, Cubs owner Charlie Murphy selected Evers as the team’s manager for 1913.48 Despite Smith securing Polly Wolfe, who played one game for the Chicago White Sox that season, the Cubs pounded the Smiths, 9-3.49 Cubs’ third baseman Heinie Zimmerman electrified the crowd with his hard hitting.50 After scoring five runs in the opening frame, the Cubs never relinquished the lead. Chicago plated another run in the second and three in the fifth. Spectators were buzzing after Zimmerman clubbed a home run and Jimmy Archer hammered a long foul ball that cleared a neighboring barn.51

Burt Keeley returned to Dwight on June 4, 1913, helming Chicago’s upstart Federal League franchise.52 Lacking a formal name, newspapers at the time frequently referred to his squad as the Keeleys, Browns, or playfully, the Keeley Cures.53,54 The Smiths played well; outhitting the minor leaguers and extended a 5-4 lead into the bottom of the fifth. The Keeleys answered with five runs and defeated Dwight, 11-7.55

With business thriving, Smith focused upon the 1916 gubernatorial election in Illinois.56 He flexed his political muscle and brought three high-profile contests to Dwight during 1915. First, the Smiths faced Chicago’s Sixth Ward Republican Club squad and lost a late-May contest, 8-2.57 Smith also arranged for two Federal League games.

On June 7, 1915, the Pittsburgh Rebels sat atop the Federal League standings, and squared off against the Smiths at West Side Park in ankle-deep mud. Player- manager Rebel Oakes tapped Charles “Bunny” Hearn to face Eddie Higgins. With a biting wind and suboptimal conditions, Oakes opted to rest his starters for the exhibition game.58 The Smiths plated five early runs and carried a 6-3 advantage into the eighth. Pittsburgh ultimately forced extra innings and plated the two winning runs on a throwing error in the top of the 11th.59

The Smiths concluded the 1915 season before a large crowd on October 12, with a 9-0 throttling by Joe Tinker’s Chicago Whales. Local rooters witnessed a game that The Pantagraph labeled “neither interesting nor spectacular.”60 Chicago’s Mordecai “Three Fingered” Brown pitched in relief and puzzled the Smiths’ batters that afternoon. After scoring three runs in the third, the Whales never looked back.

Determined to secure the Republican gubernatorial nomination in 1916, Smith’s campaign managers insisted that sports fans would vote for him. Chick Evans, winner of the 1916 US Open golf championship, endorsed Smith.61 To sway Cook County, the Friends of Col. Frank L. Smith booster club appealed to Chicago’s split baseball allegiance. The club organized with Joe Tinker as president and Ray Schalk as secretary. Other members included Buck Weaver, Jimmy Callahan, Art Wilson, Burt Keeley, Art Zangerle, and Billy Niesen.62 Despite the athletic horsepower, Smith finished third in the Republican primaries.63

After years of relentless campaigning, Smith served in the United States House of Representatives from 1919 to 1921.64 For all his political bluster, nothing significant distinguished his service. Rather than run for reelection, he sought the Senate nomination and lost.65 While serving, his connection with his baseball team is unclear as other Dwight-based teams emerged, namely the Midgets and Cubs, and the Smiths disbanded in July 1921.66,67 A team branded as the Smiths played in 1922, but Col. Smith’s connection is unknown.

Local coverage declared similar sentiments as in 1868 that “Dwight is not a baseball town,” and noted that attendance barely surpassed 200 per game.68 The Midgets were described as “remnants of the Frank L. Smiths and promising youngsters.”

Governor Len Small appointed Smith as chairman of the Illinois Commerce Commission in April 1921, a regulatory body overseeing public utilities. He served in that role until September 1926.69 During his tenure, he built powerful relations with Samuel Insull, a business magnate who controlled much of Chicago’s public transportation.70

As quickly as Smith’s team crumbled, so did his political career. In 1926 Smith ran against incumbent Illinois Senator William B. McKinley. During his campaign, rumors circulated about excessive primary expenditures. Despite these rumors, Smith defeated McKinley in a landslide and won the November election, but the Senate launched a campaign-spending investigation.71 When McKinley died unexpectedly in December 1926, Governor Small appointed senator- elect Smith to fill the remainder of his term set to expire in March 1927.

On January 19, 1928, the United States Senate, by a 61-23 vote, determined that Smith was not qualified to fill Illinois’ vacant seat due to fraud and corruption charges.72,73 The investigation determined that Smith spent more than $400,000 ($6.8 million in 2023) during the campaign and received $125,000 ($2.1 million in 2023) from Insull.74 Smith claimed, in an August 1931 open letter, that Chicago millionaire Julius Rosenwald offered him $555,000 ($9.4 million in 2023) worth of Sears Roebuck stock to withdraw his candidacy, but rejected said offer.75

Smith made a final unsuccessful run at political office in 1930. Following his defeat, he remained an active member of the Republican National Committee and continued his business pursuits in Dwight, but never organized another Dwight baseball team.76

Col. Frank L. Smith passed away at his home early in the morning on Wednesday, August 30, 1950, following a two-week illness. He was 82 years old. When he passed, Smith’s estate was valued at $400,000 ($4.8 million in 2023.)77, 78

BILL PEARCH is a lifelong Chicago Cubs fan and serves as secretary/newsletter editor for SABR’s Emil Rothe Chapter (Chicago). In 2022, he helped establish SABR’s Central Illinois Chapter. Bill has contributed to SABR’s publications about Comiskey Park, the 1995 Atlanta Braves, and has written SABR’s biographies of Dwight, Illinois’ semipro team owner Col. Frank L. Smith and Deadball Era pitcher Eddie Higgins. Bill will have two game summaries in SABR’s upcoming publication, Ebbets Field: Great, Historic, and Memorable Games in Brooklyn’s Lost Ballpark. He is happily married to a Milwaukee Brewers fan. Follow him on Twitter: @billpearch

Notes

1. “‘Big Bill’ Uses Spicy Lingo in Talks at Election Rallies,” The Baltimore Sun, April 8, 1928.

2. “He is a Candidate for Lieut. Governor,” Streator (Illinois) Daily Free Press, November 30, 1903, 1.

3. “Frank L. Smith, 82, Dies; Long a GOP Leader,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 31, 1950, 33.

4. “Brief Ball Notes,” Rockford (Illinois) Daily Register-Gazette, April 9, 1892, 3.

5. “Base Ball,” Wilmington (Illinois) Independent, June 3, 1868, 5.

6. “News Items,” The Star (Dwight, Illinois), July 23, 1868, 1.

7. The Star (Dwight, Illinois), July 30, 1868, 3.

8. Dwight Centennial Committee. Dwight Centennial, 1854-1954: A Great Past—A Greater Future (1954), 18.

9. “‘Maple Lane’ Col. Frank L. Smith’s Model Farm,” (Bloomington, Illinois) Pantagraph, July 22, 1916.

10. “Flies,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, September 9, 1899.

11. “Notes,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 25, 1900.

12. Carroll H. Wooddy, The Case of Frank L. Smith: A Study in Representative Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 71.

13. “Livingston County,” (Bloomington, Illinois) Pantagraph, June 9, 1871, 2.

14. “Military Display at Dwight, Ill.,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1874, 7.

15. “Telegraphic Brevities,” (Chicago) Inter Ocean, August 15, 1874, 4.

16. Anonymous. The Biographical Record of Livingston and Woodford Counties, Illinois (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1900), 32.

17. “Took Dwight’s Scalp,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 31, 1901.

18. Nelville S. Hoff, D.D.S., The Dental Register (Cincinnati: Samuel A. Crocker & Co., 1903), 533.

19. “Took Dwight’s Scalp,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 31, 1901.

20. Carroll H. Wooddy, The Case of Frank L. Smith: A Study in Representative Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 72-73.

21. Paul R. Steichen, “Dwight Baseball of Bygone Days Full of Interest,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 11, 1938.

22. Carroll H. Wooddy, The Case of Frank L. Smith: A Study in Representative Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 78-79.

23. “Base Ball Dope for the Fans,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, June 8, 1907.

24. “Defeated by Seattle H.S. Boys,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, July 27, 1907, 1.

25. “C.O. Schmutz, Former Major Leaguer, Dies,” Seattle Daily Times, June 28, 1962, 49.

26. “High School Boys to Take Southern Trip,” Seattle Daily Times, July 25, 1907, 15.

27. “On the Water Wagon,” Streator (Illinois) Free Press, September 19, 1907, 6.

28. Rob Edelman and Michael Betzold. “Mike Donlin,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/mike-donlin, accessed February 20, 2023.

29. “Detroit Tigers Coming,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, October 19, 1907.

30. Paul R. Steichen, “Dwight Baseball of Bygone Days Full of Interest,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 19, 1938.

31. “Detroit Tigers Coming,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, October 19, 1907.

32. “Tigers Whale Dwight,” Detroit Free Press, October 23, 1907.

33. “Ee-Yah!,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, October 26, 1907.

34. Paul R. Steichen, “Dwight Baseball of Bygone Days Full of Interest,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 19, 1938.

35. Paul R. Steichen, “Dwight Baseball of Bygone Days Full of Interest,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, August 19, 1938.

36. Genevieve Forbes Herrick. “Frank L. Smith is a Hero in His Own Home Town,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1926.

37. Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and the Golden Age of Journalism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 11.

38. “Local News,” The (Fairbury, Illinois) Blade, October 9, 1908, 14.

39. Washington (DC) Herald, April 15, 1909.

40. “F.L. Smiths Play Against the Washington Senators of the American League,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, October 17, 1908.

41. “‘Bugs’ Says He Will Behave,” Chicago Tribune, December 31, 1910, 10.

42. “Trains at Dwight,” Streator (Illinois) Daily Free Press, December 31, 1910, 5.

43. Don Jensen. “Bugs Raymond,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bugs-raymond, accessed February 20, 2023.

44. http://lockporthistory.org/dellwoodpark/dellwoodpark.htm (accessed February 16, 2023).

45. “Dwight Takes Farcical Game,” The Joliet (Illinois) News, July 31, 1911.

46. “A Resume for the Year of the F.L. Smith Club,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, December 7, 1912.

47. “Big Leaguers Defeat F.L. Smiths,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, October 26, 1912.

48. Jason Cannon, Charlie Murphy: The Iconoclastic Showman Behind the Chicago Cubs (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022), 237.

49. Paul R. Steichen, “Dwight Baseball of Bygone Days Full of Interest,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, September 2, 1938.

50. “Cubs Defeat Dwight,” The (Bloomington, Illinois) Pantagraph, October 25, 1912.

51. “Big Leaguers Defeat F.L. Smiths,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, October 26, 1912.

52. “South Wilmington,” The (Joliet, Illinois) Herald News, June 5, 1913, 7.

53. “St. Louis Feds Even Up Series with Chicagos,” The (Chicago) Inter Ocean, June 4, 1913, 13.

54. “Federals Home to Tackle Covingtons Thursday Matinee,” St Louis Star and Times, June 4, 1913, 8.

55. “Chicago ‘Feds’ Win at Dwight,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1913.

56. “1916 Pot Boiling,” The (Springfield, Illinois) Forum, March 13, 1915, 1.

57. “Home Team Wins Another Game,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, May 29, 1915.

58. “Rebels Lose in Race by Idleness,” Pittsburgh Press, June 8, 1915, 28.

59. “Win One and Lose One,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, June 12, 1915.

60. “Whales Defeat Dwight,” The (Bloomington, Illinois) Pantagraph, October 13, 1915, 5.

61. “Hull is Gaining Fast, Says Banker Friend,” Chicago Daily News, August 18, 1916, 5.

62. “Merely Politics,” Chicago Day Book, September 9, 1916, 29.

63. Carroll H. Wooddy, The Case of Frank L. Smith: A Study in Representative Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 94-95.

64. “Smith, Frank Leslie,” History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives.

65. Carroll H. Wooddy, The Case of Frank L. Smith: A Study in Representative Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 96.

66. “Defeat Dwight Midgets,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, June 25, 1921.

67. “A Tie Ball Game,” Dwight (Illinois) Star & Herald, May 20, 1922, 1.

68. “F.L. Smith Team Quits,” The (Streator, Illinois) Times, July 28, 1921, 4.

69. Carroll H. Wooddy, The Case of Frank L. Smith: A Study in Representative Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 9.

70. “The (Other) Man Who Tried to Buy a Senate Seat,” NBC 5 Chicago, June 3, 2011.

71. Sue Cummings, “Stormy Career Marked Dwight’s ‘Big Mover,’” The (Streator, Illinois) Times-Press, November 22, 1982.

72. “Senate Bars Smith by Vote of 61 to 23; Lorimer in Running,” Baltimore Sun, January 20, 1928, 1.

73. “… article about Frank L. Smith isn’t entirely accurate.,” The (Dwight, Illinois) Paper, July 6, 2022, 7.

74. “The (Other) Man Who Tried to Buy a Senate Seat,” NBC 5 Chicago, June 3, 2011.

75. “Smith Details Offer to Quit Senate Race,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1931, 3.

76. “Smith, Frank Leslie,” History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives.

77. https://smartasset.com/investing/inflation-calculator (accessed on February 19, 2023) “Frank L. Smith Estate Valued at $400,000,” The Times-Press (Streator, Illinois), September 21, 1950, 4.

78. “Frank L. Smith Estate Valued at $400,000,” The (Streator, Illinois) Times-Press, September 21, 1950, 4.