Bringing Home the Bacon: How the Black Sox Got Back into Baseball

This article was written by Jacob Pomrenke

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 26, 2006)

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in “The Journal of Illinois History” (Vol. 9, No. 4, Winter 2006) and reprinted in SABR’s “The National Pastime” (No. 26, 2006). The version below has been edited for clarity and updated with new information about the Black Sox Scandal that has come to light in the years since it was written.

For the residents of Macomb, Illinois, it was a scene straight out of the movie Field of Dreams. The infamous “Black Sox” had mysteriously showed up in their town, on their field, ready to play ball.

Only they did not emerge from a mystical cornfield on the horizon, but rather a friend’s automobile parked behind the grandstand. And “Shoeless” Joe Jackson wasn’t the only one who showed up wanting to play; he brought his teammates Eddie Cicotte and Charles “Swede” Risberg, as well.

Just five weeks removed from the “Trial of the Century” (before there was even such a designation), a trial in which they were acquitted by a cheering jury and then promptly banished from the game by baseball’s new commissioner, the three disgraced ballplayers were back in uniform together for the first* time.

The date was September 11, 1921.

* * *

Exactly one year earlier, Jackson, Cicotte and Risberg were at Comiskey Park in Chicago — as they had been for most of the previous decade — battling for the American League pennant late in the season.1 They did not realize that these were the final games of their professional careers.

On September 28, 1920, Cicotte walked into White Sox team counsel Alfred Austrian’s office and confessed that he had plotted to “throw” the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, an admission that sent shock waves around the country.2 Jackson followed Cicotte to testify to a grand jury convened in Chicago to investigate gambling in baseball. Under pressure from White Sox owner Charles Comiskey and his lawyer Austrian, both players admitted their involvement in the fix, implicating six other teammates: Risberg, Lefty Williams, Chick Gandil, Happy Felsch, Fred McMullin and Buck Weaver.3

In March 1921, indictments were handed down against the eight ballplayers and a handful of gamblers; a criminal conspiracy trial began in June.4 Under a national spotlight, it took just over five weeks before the jury declared them not guilty of conspiracy on August 2.5 But their fate was sealed that same night. As they toasted their freedom in a party with members of the jury at a local Italian restaurant6, newly appointed baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was busy preparing a statement:

“Regardless of the verdict of juries, no man who throws a game, no player that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked gamblers, where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed, and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.”7

Suddenly, their careers were over. None of them would ever set foot in a major league park again.

Cicotte, the oldest of the eight players, was just 37 years old. His only livelihood had disappeared, as had that of his teammates. Lacking any outside work experience and without the benefit of much more than an elementary education — McMullin had gone to high school in Los Angeles, but Weaver had quit school in the eighth grade and the famously illiterate Jackson was working by the time he was 8 years old8 — their prospects for the future were not bright.

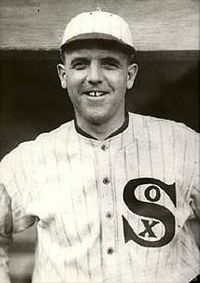

Eddie Cicotte

So the “Eight Men Out” did the only thing they knew how: they went looking for a game.

Over the next decade, they traveled throughout the country and even into Canada and Mexico just to play baseball for a living. Their road trips were not to Detroit, Boston and Washington anymore, but to dots on the map such as Douglas, Arizona; Bastrop, Louisiana; and Waycross, Georgia.9

They played together and apart, for one semipro game at a time and for whole seasons in outlaw leagues. They were celebrated and cheered by some fans, jeered and ridiculed by others. They stirred up controversy everywhere they played. It was a nomadic life that most of the players kept up for the rest of the 1920s and, for some, even into the mid-1930s. But barred from professional baseball — and taking grief from Commissioner Landis, who threatened to suspend anyone caught playing against the Black Sox — it was all they had left.10

This is how Jackson, Cicotte and Risberg found themselves suiting up for a game in a rural town in western Illinois less than five weeks after they stood on trial for conspiring to “fix” the World Series. The stakes here were much different, but they were just as meaningful to the towns involved — this was for the championship of McDonough County.

* * *

Since their inception in the early 19th century, the towns of Colchester and Macomb were engaged in a spirited battle on political, economic and cultural levels.11 The county seat (Macomb) and the mining town on the outskirts (Colchester), connected at the time by one paved road and separated by just seven miles12, were no different than thousands of other budding communities around the nation. And like thousands of other American small towns, nowhere was their rivalry more intense than on the baseball field.

Swede Risberg

By the end of World War I, both the Colchester and Macomb teams were very competitive around western Illinois, regularly beating the likes of surrounding communities such as Industry, Rushville and Bushnell, Negro traveling teams from Galesburg and Monmouth, and other barnstorming squads that passed through the area.13

On June 19, 1921 — eight days before the Black Sox trial began in Chicago — the McDonough County rivals met up at Colchester’s Red Men Park for an early-season grudge match. The field, on the northeast side of town, was maintained by the Colchester team’s sponsor, a fraternal group called the Improved Order of Red Men.14

It was a good day to root for the home team. Colchester’s 14-1 win caused Colchester Independent editor J.H. Bayless to write:

“Once upon a time, a bunch of nice young men in the city of Macomb had a dream. They dreamed that they were ball players and could beat most any team in these parts. … They undertook to use the Colchester Redmen [sic] as their first stepping stone to fame and fortune, but alas and alack, their plans miscarried and they were trampled on, figuratively speaking.”15

The over-the-top boasting surely did not sit well with Macomb’s proud civic leaders, adding an extra painful insult to the bruised egos they sustained in the loss. Macomb vowed that the two-game series on Independence Day weekend would not have the same result.16

Colchester Red Men baseball team, circa 1910s. Like thousands of other American small towns before World War II, Colchester’s civic leaders prided themselves on fielding a competitive baseball team. (Western Illinois University / John E. Hallwas)

Colchester predicted, as was the custom for many town teams in those days, that Macomb would find a way to improve its team for the next game — and they were right. Not a single one of the nine players who took the field for Macomb on July 3 had been with the team two weeks earlier.17

Macomb’s desire to win overstepped even racial boundaries. Their new shortstop and cleanup hitter was Adolph “Ziggy” Hamblin, a black player from Galesburg who was a three-sport star at nearby Knox College.18 Nearly a quarter-century before Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, employing a talented black player for an important game was not an unprecedented step for some semipro teams.19 Macomb also added, among others, a hard-hitting third baseman, “Boots” Runkle, a second baseman from Knox College named Welch, and an outfielder from Monmouth College who used the alias “Johnson.”20

Macomb’s additions had the desired effect, as Colchester managed five hits in a 3-0 loss. The second game, on July 4, was just as well-played, but Colchester pulled this one out to win 4-2 in the 13th inning on a two-run home run by one of their own new players, a right fielder named Marks.21

Both teams showed up at Red Men Park the following Sunday for what was supposed to be the deciding third game (apparently the June 21 result was discounted because both lineups had turned over so much). Macomb brought in another minor leaguer named Switzer, who had reportedly played for the Rock Island club of the Three-Eye League. Colchester took advantage of Ziggy Hamblin’s absence — which was noted but not explained by the local newspapers — to win going away, 8-4.22

* * *

Ten days after that decisive third game in Colchester, the Macomb Journal published an Associated Press article about the Black Sox trial in Chicago, which garnered national headlines all summer long.23

As the trial dragged on throughout July 1921, Shoeless Joe Jackson bided his time with friends at his successful South Side poolroom and cigar store on 55th Street in Chicago, which he had owned and operated for about a year.24 Students from the nearby University of Chicago popularized the hangout, which also might have been frequented by Henry “Kelly” Wagle on his trips to the big city. Wagle was a 35-year-old Colchester supporter who placed more than a rooting interest in the team’s games against Macomb — usually a few dollars or more.25

Henry “Kelly” Wagle

In Colchester, Wagle cultivated his image as a philanthropic businessman, generous to one and all, raised by an upstanding family, respected around town — and he was all of those things — but everyone knew what he really was: a bootlegger.26 Prohibition had opened the doors to organized crime in America’s small towns, and Wagle was one of the most successful at his chosen profession this side of Al Capone. In fact, he soon became friends with the notorious mob boss27, and Wagle often drove one of his flashy automobiles — in 1921 alone, he owned a black Ford, a white Cadillac and a blue Marmon28 — across Illinois’ rural highways to meet Capone. In those years, Wagle acquired most of his alcohol from a supplier at 35th and Halsted streets in Chicago, about eight blocks from Comiskey Park, and near where many of the White Sox lived.29 The sociable Wagle no doubt struck up conversations with the players and likely even slipped them a quart of “booze” from time to time.30

It was an especially difficult summer for the ballplayers, because baseball had turned its back on the “Eight Men Out.” However, they still had plenty of opportunities to play for money — even in Chicago, where they passed the hat around the bleachers at White City Ball Park on Sunday afternoons before the trial began in July.31 Hundreds of fans showed up at the corner of 63rd Street and South Park Avenue each weekend to see Jackson, Cicotte, Risberg, Gandil and Williams, on a team promoted as the “South Side Stars,” play the likes of the local Elks’ Club, the “Nebraska Indians” and the “Woodlawns.”32

The Black Sox did not lack for offers to play in other cities, either. The Boston Globe reported that more than 50 towns had invited one or more of the players to a Sunday game, even as the trial was going on. The article stated that Jackson was “sought by half a dozen Wisconsin towns,” Williams was wanted by “several Iowa points” and Cicotte had turned down several requests “as to whether he could pitch tomorrow [July 25].”33

While some of the more lucrative — and nearby — offers were eagerly accepted, many were turned down for various reasons, not the least of which was that the possibility of jail time was still very real. So mostly they stayed at home in Chicago; Jackson managing his poolroom, Weaver tending his drugstore, Cicotte taking care of his family, all laying low on the south side.34

When Kelly Wagle made contact to ask for their assistance and athletic expertise in his hometown of Colchester, the request was likely met with indifference at first. But Wagle had a charming way of disarming even the most guarded of exiled ballplayers, and his advances did not go unnoticed.35 There would be money in it for the players, of course, and no hassles other than the customary catcalls from the bleacher bums when they showed up for the game — nothing they weren’t used to by now. All Wagle asked was that the players not tell anyone but him if they chose to accept.

In the meantime, Lefty Williams was receiving a similar offer from backers of the Macomb team.36 Wagle had known about this ahead of time, having made it his habit as a bettor to be prepared for situations before they occurred, but he figured that Williams would not want to leave his wife, Lyria, in Chicago and travel to Macomb (250 miles away) for a game so soon after the trial. Wagle’s assessment was accurate: the lefthander would not be pitching for Macomb or Colchester, not now, not ever.37

But Jackson seemed willing to listen to Wagle’s offer, as did Risberg and Gandil, the two purported ringleaders of the 1919 World Series fix. Cicotte was also interested; after declining most of his non-Chicago offers from various promoters during the summer, “Knuckles” said he wouldn’t mind suiting up, too.38

First, however, there was another game to play.

* * *

While Colchester was busy courting the Black Sox, Macomb was securing the services of a right-handed fireballer who called himself “Frank Smith.” Although his identity was never revealed, it was reported that Smith was a former hurler in the Three-Eye League and a St. Louis Browns farmhand.39 While his background and his pedigree remained a mystery, his talent was decidedly not. After joining Macomb in mid-July, Smith dominated in his first two starts over Bushnell and Industry, leading the Macomb Journal to boast that it was the clear — if unofficial — champion of McDonough County, which brought a quick rebuke from Bayless.40

A game was scheduled for August 21 at Red Men Park, and talk soon began to swirl that both teams were trying to recruit more “ringers” for the highly anticipated contest. On August 18, the Macomb By-Stander reported that “rumor had it” Colchester was on the verge of bringing in players from Chicago — which was only half right. Colchester showed up for the game with two players from the University of Chicago, catcher Clarence Vollmer and a top semipro pitcher called “Adams.”41

Macomb countered with another minor leaguer, Jimmie Connors of Rock Island’s Three-Eye League club, who played first base for Macomb. Now their roster was comprised of four collegiate players and three minor-leaguers, including the pitcher.42 It was an imposing lineup and also a successful one. Frank Smith was his usual impressive self against Colchester, “a complete master of the situation from beginning to end” in a 4-0 shutout.43

It was “the most sensational game played in the mining city in the last decade,” boasted the Macomb Journal — an exhibition worthy of an encore. A fifth and final game had already been scheduled, for September 11 at Macomb, before the 1,300 spectators had even cleared the grounds.44

The upcoming “championship” game was the talk of both towns immediately afterward, and it would continue to be so until September 11 — three weeks away. J.H. Bayless made a seemingly innocuous remark near the end of his game story in the Colchester Independent: “We believe that we can improve the team a little with some of our home boys.”45 Bayless wasn’t aware that the same idea had already passed through Kelly Wagle’s mind.

* * *

In the Macomb Journal, just below the box score signifying Macomb’s victory over Colchester was a small box, labeled, “This Time Last Year.” The final item mentioned that the Chicago White Sox were leading the American League standings one year ago — on August 22, 1920.46

But that didn’t matter to Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte and their six former White Sox teammates — their major-league careers were over for good. Commissioner Landis, a federal judge in Illinois since 1905, had laid down his own brand of the law when the law had failed to find the players guilty of any crime. His announcement that banned the players for life came just hours after the verdict was handed down in Chicago.47

Organized baseball quickly made it clear that the “Eight Men Out” would not be welcomed back. The National Association, the game’s ruling body, announced that it would not allow any of the Black Sox to play in the minor leagues, while many semipro leagues, such as the Lake Shore League in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, voted against the players’ participation, as well.48

The residents of McDonough County, however, had no such referendum on which to vote for or against the “baseball crooks.” Kelly Wagle was very good at keeping a secret — his darkest one would not be uncovered until a year after his death.

Wagle’s early efforts to secure the Black Sox had paid off. In addition to Jackson, Cicotte and Risberg, Chick Gandil had also agreed to play against Macomb for a reasonable fee — in advance, of course.49 They had learned from their bungled World Series fix, when only Cicotte had received, on demand, a payment before Game One. Gandil had spent the rest of the Series begging the gamblers for the money he had promised his teammates, with little success.50

The Black Sox did not always ask for their money up-front; they knew that usually they could rake in far more by passing the hat around the bleachers during the game.51 But because their participation was to be unveiled on the day of the game, there would not be enough time to promote their presence, which was sure to bring in a larger crowd. While no records exist showing how much Wagle offered to pay the players, they likely received about $250 apiece, give or take a bottle of whiskey. That was the equivalent of two weeks’ salary for a major-league player making $6,000 per year, and easily affordable for Wagle.52 He planned to make much more on the game itself.

Money — whether it was because they were paid poorly (editor’s note: they were not) or they simply were greedy — was a prime motivating factor for the Black Sox to consider fixing the World Series back in 1919. It was also the reason the players were willing to suit up for Colchester against Macomb. Because of their suspensions, they no longer were receiving paychecks from the White Sox.53 Jackson, Weaver, Risberg, and Felsch later sued the team for back pay owed to them, but these cases were not resolved until years later, when it was getting harder for them to make ends meet simply by playing semipro and outlaw games around the country.54 A hundred dollars or two for an afternoon’s work was easily worth the effort.

* * *

Meanwhile, baseball fever was rising throughout McDonough County as the calendar turned to September.

Macomb’s confidence was high in the days leading up to the “championship” game on September 11. The Journal wrote, “With a team not considered as fast as this, they defeated the Colchester importations before, and they believe they can do it again.”55

By all accounts, Colchester’s team had not changed. They still had “the three Chicago players engaged that they secured before, according to the dope from that city.”56 None of the three newspapers in McDonough County even hinted at the possibility that “the three Chicago players” were any different than Vollmer, Adams, and a semipro catcher by the name of “Kid” Standard, who was a distant relative of Dr. A.P. Standard, the newly elected president of the Macomb Fairgrounds Association.57 Kelly Wagle’s secret was secure.

On Saturday, September 10, Wagle was busy meeting four out-of-towners who had arrived on the 6:18 p.m. train from Kansas City.58 It was Jackson, Cicotte, Risberg and the catcher, Standard. Chick Gandil had also traveled with them from Oklahoma but missed the train in Kansas City after calling on some friends between connections. Before the ballplayers could be noticed by anyone in town, Wagle quickly whisked them up to Bushnell, a small community 15 miles northeast of Macomb, where they spent the night.59

Finally, after all the hype that had been building for four months, it was time for the big game between Colchester and Macomb — a game that would be talked about in McDonough County for years to come.

* * *

Sunday, September 11, 1921, arrived quietly but with great anticipation. Game time was set for 3 p.m. at the Macomb Fairgrounds, and a typically large crowd was expected there when the unofficial championship of McDonough County was to be decided.60

As the fans trickled in to the ballfield, where additional wooden bleachers had been set up down the foul lines to accommodate the throng that would reach 1,611, they noticed nothing out of the ordinary.61 Adams was warming up with Clarence Vollmer on one side of the diamond, while Frank Smith was on the other side loosening up his arm with his catcher, a minor-leaguer named Wilson. Members of the Macomb team joked with some Colchester players, asking them “if they wouldn’t strengthen up a little in order that the fans could be insured [sic] of a good game.” They didn’t know what they were in for.62

After a long pregame workout, and the crowd had gotten settled, three players in “rather seedy-looking uniforms” with World War I stars on their jerseys emerged from Kelly Wagle’s automobile behind the grandstand. They began to play catch amidst “a painful silence” as the spectators strained to recognize their vaguely familiar faces.63

Then, umpire Clifford McPherron — who Colchester tried to keep out of the game because he had once played for Macomb years before — stepped to home plate and announced the pitching matchups for both teams: “Battery for Colchester, Cicotte and Standard; Macomb, Smith and Wilson.”64

According to J.H. Bayless in the Independent, it was “the surprise of a lifetime, as no one could conceive of the bigness of the deal, not thinking Colchester was able to handle a deal of this magnitude.”65

After the initial shock set in, the Macomb fans jeered lustily and team promoter Art Thompson protested that the game should not be played with the “blackest of the Black Sox” present. Noting the red, white and blue rings on Cicotte’s stockings — similar to those worn by the White Sox during the 1917 World Series — one heckler shouted, “You’ve got a lot of guts to wear those colors.” When he came to bat, Jackson was “frequently reminded of his record of working in the ship yards instead of Uncle Sam’s army during the war.”66

Eddie Cicotte warms up before a game in the 1917 World Series at Comiskey Park in Chicago. For the Series,just months after America entered World War I, the White Sox wore patriotic uniforms with American flag patches on both sleeves and red, white, and blue stockings. (SDN-057908C, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum)

The Black Sox players, however, had heard it all before and were not fazed by the negative reaction they received from the Macomb side. The Macomb fans had reason to be distressed. As the game began, it was clear that Cicotte was as sharp as he had ever been in the American League. A roster of college boys and imported minor-leaguers, even though it had dominated the local competition all summer, was no match for the knuckleballer’s dazzling array of pitches — the emery ball, drop ball, and, of course, his famous “shine” ball — which had helped him win 208 games, including 35 shutouts, since 1908.67

Bayless explained: “Cicotte simply toyed with the batters, not passing a man and striking them out when necessary. (Connors) of Rock Island, the idol of Macomb fans, struck out every time he was at bat. … Not a member of the Macomb team saw second except [umpire] McPherron!”68

Cicotte allowed just four singles — all but one of those coming to the bottom half of the order — and struck out 10. He bared down especially hard on Wilson, per request of Kelly Wagle, who was said to have bet that the Macomb catcher would not record a hit.69 Wilson struck out all three times and did not so much as register a foul tip.

Jackson and Risberg were equally impressive in the field. On one base hit by Boots Runkle to left, Jackson “loafed” a little to bait Runkle into trying for second, which he did. But “old Joe tried out his good right arm and Risberg did the rest.” For his part, Risberg chased one high fly deep into the outfield and made a running catch over his shoulder that brought many cheers from the Colchester side.70

The presence of the Black Sox even seemed to elevate the play of their teammates, as Clarence Vollmer and Kid Standard each recorded two hits and the third baseman, Boyle, had a double and two singles. Cicotte gave his club the lead in the second inning, as Hamblin muffed his hard grounder to short, letting Standard score with the first run. Risberg also drove in the former Chicago ace with a run in the fourth. Jackson (who had an off-day, going 1-for-5 with a strikeout), Adams, and Vollmer all scored, while every starter but John Kipling recorded a hit.71

Colchester’s 5-0 victory was a decisive one, and the debate over its legitimacy had already begun long before the game was over.

Both Macomb newspapers were heavy-handed in their criticism of Colchester, noting, “They allowed a desire to win a game to override their better judgment on sportsmanship in general. … It is certain that the local team will not again play against those players whom Judge Landis has barred from professional baseball because of their alleged crookedness.”72

The By-Stander added: “Colchester won a ballgame yesterday and Macomb lost one — but both teams lost something that means a lot more than winning or losing. … It is not ‘sport’ to engage or play these men who have sold out their clubs and their friends. If the ‘Black Sox’ are ‘out in the sticks to get the money,’ as one player put it, the By-Stander won’t give any of its space to help them do it.”73

Colchester fans — and in particular, the unabashed Independent editor, J.H. Bayless — were nothing short of ecstatic after “pulling over a fast one” on the county seat.74 He wrote: “A mighty cheer went up from those from Colchester, Industry, Rushville, Bushnell and nearly every place except Macomb. … Even when Cicotte, Risberg and Jackson — men of worldwide reputation, perhaps the best there is — were making apparently impossible plays, the Macomb fans refused to be moved to cheers. We don’t wonder, for they are a hard bunch of losers.

“The Colchester Redman Base Ball team are champions of McDonough County.”75

* * *

Following the game, an anonymous poem (perhaps written by Bayless) was published in the Colchester Independent on September 15. The headline read “Championship Baseball Game”:

Old Cicotte played ball the other day,

Old Cicotte taught the boys how to play

The rooters and the fans, of course, had a lot of fun,

And it didn’t take old Cy long to show them how it was done.They wouldn’t allow us to have an ump, but of course they didn’t care,

For when old Cy pitched the ball, their bat it wasn’t there.

And we beat them on the square.

Some felt a little sorry for the team of the County Seat —

But of course they had a reason, for they bet on the mining town’s defeat.They say they played Chicago, well what if they did?

We had to play Galesburg, Monmouth, Rock Island and St. Louis and still we didn’t kid.

Hamblin and Howell, the County Seat stars,

Were shown up right by this little team of ours.When Cy threw the ball, Old Doc he couldn’t see,

But maybe this was due to the lack of a patch upon his knee.

Well, the little old mining town isn’t afraid to spend the ‘mon’

And when old Cy didn’t let them have a run,

We rode right home with the bacon and the beans

And now we are Champions of McDonough County teams.And the little old By-Stander, the Democratic press,

We see they have their stinger out but one thing they don’t confess,

They tried to hire “Lefty” Williams, the ‘Black Sox’ indeed.

See, the color didn’t matter, they wanted the man who had the speed.But being unsuccessful this Black Sox to obtain,

They have started in to ragging, they have an awful pain.

You can’t hurt old Cicotte with your foul mouth and pen,

For the courts have proved him innocent of the lying tongues of men.Now if you cannot take your medicine, and smile upon the flowers,

We’ll send you back the beans, but the bacon sure is ours!76

* * *

Speeding out of the Macomb Fairgrounds after the game, with the Black Sox and Kid Standard in tow, Kelly Wagle could not have been more satisfied with his celebrated accomplishment.

But his story — and the players’ — was one of dark secrets and tragic endings.

The skeleton in the players’ closet was, of course, well known. They would pay for their sins every time they stopped on a ramshackle field in some rural town, knowing that their skills were more suited for a well-manicured diamond in a major-league city.

Shoeless Joe Jackson, by far the most famous of the banished eight, went back to his dry-cleaning business in Savannah, Georgia, and was largely forgiven by the Southern people he so dearly loved. They still considered Jackson one of their own, and his smashing line drives and circus catches earned him great acclaim when he led his Americus, Georgia, team in the independent South Georgia League to the “Little World Series” championship in 1923. He was “the biggest attraction the league ever had.”77

Later, he moved back home to Greenville, South Carolina, and opened a successful liquor store on the west end of town. He finally stopped playing baseball in the mid-1930s, around the age of 45, but continued teaching youngsters the game and stayed involved in the game. A few years later, he was invited to serve as chairman of the protest board for the Western Carolina Semi-Pro League and he held the post for the rest of his life.78

Jackson continued to deny his involvement in the Black Sox Scandal, and said, “I know in my heart that I played to the best of my abilities.”79 He died of a heart attack on December 5, 1951, just days before he was to appear on a television special to publicize his case for reinstatement.80

Eddie Cicotte stayed around Chicago for another year and played ball with Risberg (and sometimes with and against Felsch, Weaver, or Williams) on a barnstorming team called the Ex-Major League Stars in 1922. But he and Risberg had a falling-out that summer after Cicotte demanded his money up-front and the shortstop responded by punching him in the mouth, knocking out two of his teeth!81

After 14 years in the big leagues and another two years playing exhibition games in Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin, Cicotte had grown tired of being away from his family all the time, so he moved back home to his farm outside Detroit. He continued playing ball on infrequent occasions, but made his living working in the Ford Motor Company service department in Highland Park, Michigan, and spent his final years raising strawberries.82

He disappeared from the public eye until 1963, when Eliot Asinof’s authoritative work on the 1919 World Series scandal, Eight Men Out, was published. He gave several interviews thereafter and expressed regret for his role in the scandal. Cicotte died quietly at age 84, on May 5, 1969, in Farmington, Michigan.83

Swede Risberg moved to Rochester, Minnesota, and bought a farm there in the early 1920s. But he spent the rest of the decade touring the northern part of the country and Canada — often playing with or against Happy Felsch — during the summer.84

Like many barnstorming stars, Risberg found that more money could be made as a pitcher and, while he had only pitched professionally in the low minor leagues as a teenager, he spent most of his post-major-league career on the mound. His travels took him to Duluth and Hibbing, Minnesota (1922-24), Scobey, Montana (1925), Watertown and Lignite, South Dakota (1926-27), Manitoba and Saskatchewan (1927-29), Jamestown, North Dakota (1929-30), Sioux Falls, South Dakota (1931-32), and Klamath Falls, Oregon (1934-35) before he finally hung up his spikes for good.85

In 1927, he and Chick Gandil became “the center of baseball controversy” after claiming that the entire White Sox team had paid members of the Detroit Tigers to intentionally lose games to them ten years earlier. Judge Landis called for an investigation and they went to Chicago, along with dozens of other major league stars — including their ex-Black Sox teammate, Buck Weaver — to testify in the matter. But Weaver failed to corroborate their story, instead making a dramatic plea for his own reinstatement, and Landis dismissed the charges. Quietly, Risberg returned home to Minnesota.86

The Great Depression hit Swede and his family hard, as it did millions of other Americans, and they lost their home, a car agency, a hotel and their farm.87 Risberg worked many odd jobs for the next two decades — including shoveling corn for a dollar a day in Sioux Falls, South Dakota — before opening a successful nightclub called “Risberg’s” on the California-Oregon border.88 He was interviewed for a regular column in the Red Bluff Daily News during the 1970 World Series, providing analysis on Brooks Robinson, Pete Rose, Jim Palmer and Johnny Bench, et al, (although he erred on his prediction of Cincinnati to win).89

Risberg remained in good health over the years, despite walking with a decided limp for most of his life. An old spike wound that had never healed forced him to get surgery — still a risky procedure before World War II — which gradually deteriorated the circulation below his knee. Later in life, after moving in with his son Robert’s family in Red Bluff, Risberg’s leg was amputated and he spent his final years in a wheelchair at a convalescent home. He died of cancer on his 81st birthday, October 13, 1975, the last surviving member of the Black Sox. Unlike most of his banished teammates, he rarely claimed innocence or applied for reinstatement from baseball.90

Kelly Wagle, the mastermind of Colchester’s most memorable victory, continued circumventing the law throughout the Roaring Twenties, doing his best to avoid persecution by the various civic leaders brought in to “clean up” McDonough County.

He was arrested for the first and only time in 1927, when he spent six months in jail for illegally possessing and transporting liquor.91 But soon he was back to bootlegging, expanding his operation all the way to Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri with the help of several partners.92 But with greater success also came threats to that success, and Wagle had a history of using the same violent methods favored by his friend Al Capone to dispel those threats.93

Back in 1919, Wagle had quietly followed his wife Beulah to Omaha, Nebraska, after she had sold $1,400 worth of his alcohol to a bootlegger from Galesburg and left town with her lover. On November 20, a woman’s body was found with a bullet wound in her head, lying face-down at the bottom of an embankment near a little-used country road outside of Omaha.94 The Omaha Bee published a gruesome photograph of the corpse asking for help in identifying her, but no one was able to. The crime remained unsolved … for 11 years. In 1930, two enterprising reporters for the Omaha World-Herald, with the help of a Chicago Tribune staffer, located Beulah’s father in nearby Carthage, Illinois, and finally confirmed (through dental records) the identity of the “Omaha Mystery Girl”: Beulah Wagle.95

Back in 1919, Wagle had quietly followed his wife Beulah to Omaha, Nebraska, after she had sold $1,400 worth of his alcohol to a bootlegger from Galesburg and left town with her lover. On November 20, a woman’s body was found with a bullet wound in her head, lying face-down at the bottom of an embankment near a little-used country road outside of Omaha.94 The Omaha Bee published a gruesome photograph of the corpse asking for help in identifying her, but no one was able to. The crime remained unsolved … for 11 years. In 1930, two enterprising reporters for the Omaha World-Herald, with the help of a Chicago Tribune staffer, located Beulah’s father in nearby Carthage, Illinois, and finally confirmed (through dental records) the identity of the “Omaha Mystery Girl”: Beulah Wagle.95

By then, however, Kelly Wagle was dead — murdered in a drive-by shooting on the streets of Colchester on April 8, 1929.96 His death was never officially solved, but as his widow, Blanche, told a local newspaper later, “Everybody knows who did it.” Wagle’s gangland-style death — orchestrated by his former partner-turned-chief rival, Jay Moon, who was engaged to Kelly’s sister97 — was reminiscent of something put on by Al Capone, such as the infamous “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre” that occurred in Chicago earlier that year.98

It also signaled the end of an era for Colchester.

The death of the most notorious man in McDonough County brought about a revitalized effort to enforce Prohibition and bring a stop to the violence and lawlessness of the bootlegging days. After the 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933, Colchester voted not to allow alcohol sales four years later — and the town has been dry ever since.99

Macomb discontinued its Independence Day fair in 1928 and the Fairgrounds was sold to the city’s Board of Education two years later. All the buildings were removed, except for an old horse barn in the southwest corner of the grounds. The baseball field where the Black Sox had once played became the high school’s athletic facility for the next decade, but it fell into disrepair and was abandoned by World War II, then deeded to the state for an armory site.100

But the extraordinary events that took place on September 11, 1921, were never forgotten. For one day, at least, Macomb was a major-league city with major-league baseball. And for that one day, because of the slick ingenuity of Henry “Kelly” Wagle, the Colchester Red Men team was the champion of McDonough County.

* When this article was originally published, this game in Macomb was the first known instance that Jackson, Cicotte, and Risberg all played together after Judge Landis banned them for life. However, new research by Ron Coleman has shown that the trio, along with Chick Gandil, also played in a series of games in Oklahoma during August 1921, just after their criminal trial ended. (See Ron’s article in the June 2018 SABR Black Sox newsletter for details.) More than 1,000 ballgames involving one or more of the Black Sox players following their ban from baseball have now been documented by the author.

Photo Credits

BlackBetsy.com, Chicago History Museum, Western Illinois University / John E. Hallwas, Macomb Journal, Colchester Independent, Chicago Tribune.

Notes

1 “1920 Chicago White Sox,” BaseballLibrary.com; www.baseball-reference.com

2 Crusinberry, James, “Two Sox Confess; Eight Indicted; Inquiry Goes On,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1920; “Men’s Confessions Shock Boston Fans.” Boston Globe, September 29, 1920.

3 Asinof, Eliot, Eight Men Out (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1963), 160-61, 169-74; Gropman, Donald, Say It Ain’t So, Joe (New York: Lynx Books, 1988), 183-85

4 Asinof, 228-31; Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1921. Indictments against the Black Sox and five gamblers were originally returned on November 6, 1920, but a new State’s Attorney was elected in Cook County that fall and complications with the original prosecution led to the strategic dismissal of the first indictments. Another grand jury was convened in the spring of 1921 and new indictments against the Black Sox and a total of ten gamblers were returned on March 26, 1921. For a comprehensive analysis of the Black Sox legal proceedings, see Lamb, William F., Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial, and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina; McFarland & Co., 2013).

5 Crusinberry, James, “Jury Frees Baseball Men.” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1921.

6 Asinof, 273; Crusinberry, “Jury Frees Baseball Men”

7 Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1921.

8 Los Angeles Times, March 25, 1936; Gropman, p17

9 Washington Post, October 13, 1925; November 29, 1925; Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1927; New York Times, July 12, 1923; Alexandria (Louisiana) Town Talk, July 11, 1923; Atlanta Constitution, August 30, 1923; Bell, John, Shoeless Summer (Carrollton, Georgia: Vabella Publishing, 2001); Bevill, Lynn E., “Outlaw Baseball Players in the Copper League: 1925-27,” master’s thesis, Western New Mexico University, 1989.

10 “Weavers Win Two,” Chicago Tribune, June 13, 1932; June 27, 1932; Lardner, John, “Joe Jackson’s Playing Stirs Up Dixie League,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1934; Muchlinski, Alan, After the Black Sox: The Swede Risberg Story (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2005).

11 Hallwas, John. The Bootlegger (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 59-60, 131-33.

12 Hallwas, 215-17.

13 Colchester Independent, June 23, 1921; July 7, 1921; July 20, 1921; June 1, 1922; Macomb Daily Journal, July 15, 1921; August 22, 1921; August 29, 1921; September 6, 1921.

14 “Macomb Fair Grounds Sold,” Macomb Journal, April 16, 1921; Hallwas, 184

15 Bayless, J.H., “An Awful Beating,” Colchester Independent, June 23, 1921.

16 Ibid. Macomb fans reportedly engaged in “insulting personal remarks,” prompting editor J.H. Bayless to respond, “A person should be broad enough to recognize good play on the part of (his opponent).”

17 Ibid; Macomb Journal, July 5, 1921; Bayless, J.H., “We Win and Lose,” Colchester Independent, July 7, 1921.

18 Hallwas, “Bootlegger notes.” Western Illinois University library archives.

19 Muchlinski, 6-7, 64-66; Dawson, David D., “Baseball Calls: Arkansas Town Baseball in the Twenties,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1995; Bevill, “Outlaw Baseball Players in the Copper League: 1925-27.”

20 Hallwas, “Bootlegger notes;” Bayless, “We win and lose;” Macomb Journal, July 5, 1921.

21 Macomb Journal, July 5, 1921.

22 Bayless, “Wins From Macomb,” Colchester Independent, July 14, 1921; Macomb Journal, July 20, 1921.

23 “Tells Inside of Baseball Scandal,” Macomb Journal, July 20, 1921.

24 Lardner, John, “Remember the Black Sox?” Saturday Evening Post, April 30, 1938; Hallwas, “Bootlegger Notes;” Gropman, 202-04.

25 Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 132, 186; Hallwas, “Bootlegger notes.”

26 “Hold Services For T.H. Wagle at Colchester,” The (Carthage, Illinois) Gazette-News, April 12, 1929; Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1930; Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 156-58, 177-79, 192.

27 Hallwas, 220-21.

28 Ibid, 180.

29 Ibid, 178.

30 Ibid, 155, 178-79, 232-33. In the early 1920s, Wagle bootlegged “mostly to people he knew. … Although he sometimes sold liquor from his house, Kelly often took it to his customers. … It was a safe operation as long as he was cautious.” After he got out of jail in 1927, Hallwas writes, he stopped selling to individuals and sold more to small-time bootleggers: “It was simply safer to deal with men who had the same interest in avoiding the authorities.”

31 “Accused Players Prosper,” New York Times, July 1, 1921; Rundio III, Stephen J., “From Black Sox to Sauk Sox,” 1997 SABR Research Symposium.

32 Classified advertisements, Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1921; June 25; 1921; July 2; 1921.

33 “Black Sox in Heavy Demand,” Boston Globe, July 24, 1921.

34 Kilgallen, James F. “Weaver Now Waiter For Soda Font,” Atlanta Constitution, November 21, 1920; Hallwas, “Bootlegger Notes;” Gropman, 202-04.

35 Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 183-84. As his professional career blossomed in the early 1920s, Kelly Wagle “developed an enormous reputation for good deeds.” He was known for giving kids ice cream on his front porch, bringing food to families in need, offering rides to a neighboring town. In 1921, when Colchester High School organized its first football team, Wagle bought their uniforms and let them practice on his land after the school’s budget came up short.

36 Bayless, “Macomb is Shut Out,” Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921; “Black Sox Here,” Macomb Journal, March 23, 1922.

37 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921; Macomb Journal, March 23, 1922.

38 Gandil, Arnold, as told to Melvin Durslag, “This is My Story of the Black Sox Series.” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956.

39 “Chester Loses to Macomb Vets,” Macomb Journal, August 22, 1921; Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

40 Bayless, “Who are Champions?” Colchester Independent, August 4, 1921.

41 Macomb Daily By-Stander, August 18, 1921.

42 Ibid; Bayless, “Macomb is Winner,” Colchester Independent, August 25, 1921.

43 Macomb Journal, August 22, 1921.

44 Ibid

45 Colchester Independent, August 25, 1921.

46 Macomb Journal, August 22, 1921; “1920 White Sox,” www.baseballlibrary.com

47 Spink, J.G., Judge Landis and Twenty-Five Years in Baseball (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1947); Asinof, 223-24; Gropman, 195-98; Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1921.

48 Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1921; Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1921.

49 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

50 Asinof, 90-91, 100-01, 103.

51 Muchlinski, 3-4, 8-11, 34-35, 44-45.

52 The contract cards that Chicago White Sox management filed to the American League president’s office for the 1919 season are held in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s library archives in Cooperstown, N.Y. According to the cards, Joe Jackson was contracted to be paid $6,000 for the season. Eddie Cicotte was contracted to be paid $5,115. Swede Risberg was contracted to be paid $3,250. How much was actually paid out to the players by the Chicago White Sox team is unknown.

53 Asinof, 179-80.

54 Asinof, 288-292; Gropman, 208-211. Joe Jackson’s civil case against the White Sox went to trial in January 1924 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. When he took the stand, he was confronted with his grand jury testimony from 1920 and denied giving any of that testimony even when it was read back to him. The Milwaukee jury awarded him more than $16,000 of back pay, but the judge immediately vacated the verdict and ruled that Jackson had perjured himself. Weaver, Risberg, and Felsch’s lawsuits against the White Sox were quietly settled. For a more detailed analysis, see Lamb’s Black Sox in the Courtroom.

55 “Macomb Will Have A Strong Team,” Macomb Journal, September 9, 1921.

56 Ibid.

57 “Macomb Fair Grounds Sold,” Macomb Journal, April 16, 1921.

58 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

59 Ibid.

60 Bayless, “Big Game Sunday,” Colchester Independent, September 8, 1921.

61 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921; “ ‘Black Sox’ Give Macomb A Lacing,” Macomb Daily By-Stander, September 12, 1921.

62 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

63 Ibid

64 Macomb Daily By-Stander, September 12, 1921; Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

65 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

66 Macomb Daily By-Stander, September 12, 1921; “Colchester Slips One Over and Wins,” Macomb Journal, September 12, 1921; Stein, Irving, The Ginger Kid: The Buck Weaver Story (Dubuque, Iowa: Elysian Fields Press, 1992), 99.

67 “Eddie Cicotte,” www.baseball-reference.com.

68 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921; “A Line O’ Type or Two: Mr. Wagle,” Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1962.

69 Hallwas, “Bootlegger notes;” Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

70 Macomb Journal, September 12, 1921; Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 186.

71 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

72 Ibid.

73 Macomb Daily By-Stander, September 12, 1921; Macomb Journal, September 12, 1921; “The Black Sox,” Macomb Daily By-Stander, September 16, 1921.

74 Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

75 Ibid.

76 “Championship Baseball Game,” Colchester Independent, September 15, 1921.

77 Gropman, 202-04; Bell, Shoeless Summer.

78 Gropman, 218; New York Times, December 6, 1951.

79 Bisher, Furman. “This Is The Truth!” Sport Magazine, October 1949.

80 New York Times, December 6, 1951; Asinof, 292-93; Gropman, 225-29.

81 Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1922; Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1922.

82 New York Times, May 9, 1969; Lardner, John, “Remember The Black Sox?” Saturday Evening Post, April 30, 1938; Asinof, Eight Men Out.

83 Falls, Joe, “46 Years Later — A Visit With Ed Cicotte,” Baseball Digest, February 1966; New York Times, May 9, 1969.

84 Muchlinski, After the Black Sox: The Swede Risberg Story.

85 Washington Post, January 10, 1927; Lardner, “Remember The Black Sox?”; Muchlinski, 56-61.

86 Chicago Tribune, January 5-7, 1927; March 13, 1927; New York Times, October 16, 1975.

87 Muchlinski, 107-08.

88 Ibid.

89 Red Bluff (California) Daily News, October 9, 1970; October 12, 1970; October 16, 1970.

90 Smith, Red, “Last of the Black Sox,” New York Times, November 2, 1975.

91 Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 229-32.

92 Ibid, 228.

93 Ibid, 205-08. In one incident, Kelly Wagle was suspected of bombing the Macomb City Hall and circuit court judge T.H. Miller’s house in 1925, soon after he was arrested for “possessing, storing, and transporting intoxicating liquor in the City of Colchester.” He was found not guilty after the evidence — two gallons of liquor confiscated from his home — was “stolen,” presumably by Wagle himself.

94 Ibid, 164; “Slain Woman is Identified by Kin After 11 Years,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1930.

95 Hallwas, 258; Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1930; “Mystery Girl, Dead 11 Years, Identified,” Washington Post, August 24, 1930.

96 Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 247-52; Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1930.

97 Hallwas, The Bootlegger, 227, 248-49, 262-66.

98 Helmer, William J. and Bilek, Arthur J., The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (Nashville, Tennessee: Cumberland House Publishing, 2006.

99 Ibid, 266.

100 Western Illinois University archives, “Macomb Fairgrounds.”