Brother on the Wall: Spike Lee’s Jackie Robinson

This article was written by Joshua Neuman

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

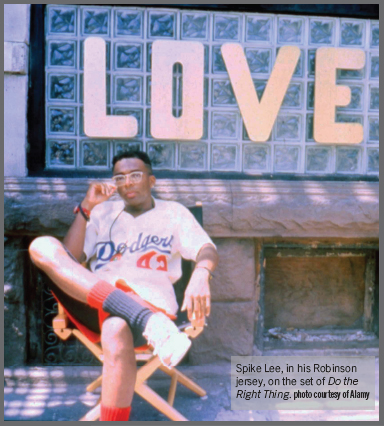

Spike Lee, in his Jackie Robinson jersey, on the set of Do the Right Thing. (Courtesy of Alamy)

In an Instagram post on March 29, 2020, Spike Lee announced that he would be sharing the 155-page fifth draft of a script for a Jackie Robinson biopic, which he wrote in 1996. The project, he wrote, was an “epic dream” of his that was never realized. The post came at the beginning of a global pandemic and worldwide shutdown and with baseball spring training canceled and the regular season delayed, the never-been-seen script was a window into baseball’s past as well as a proxy for its present. As such, it was widely covered by the media with more than a few observers using the occasion to mention that Lee was set to become the first Black president of the Cannes Film Festival,1 an implicit comparison between Robinson’s efforts as a trailblazer and those of Lee.

It wasn’t the first time the comparison had been made. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. once described Lee as “the Jackie Robinson of the film community.”2 Both Robinson and Lee have been celebrated as trailblazers, but also criticized for being too militant by mainstream Whites and as sellouts by some Black critics. As a result, making Robinson his subject in a film would be a way for Lee not merely to interrogate the representation of an African-American icon, but also to think about his own meaning as a Black filmmaker.

The script was not the first time that Lee pays homage to Robinson. There have been several over the course of his work—many referencing one another. School Daze (1988), the follow-up to his debut film, begins with a photo montage depicting the African-American struggle in the United States going all the way back to the slave ships. A Jackie Robinson still is featured first in a sequence of iconic Black athletes including Willie Mays, Muhammad Ali, and Joe Louis. It’s worthy of note because a series of photos lies at the heart of the drama of a film that Lee would release the following year, Do the Right Thing (1989). Those photos belong to the “Wall of Fame” inside Sal’s Famous Pizzeria in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, but they are of Italian-Americans rather than African-Americans— this despite the fact that the vast majority of the establishment’s patrons are Black. Tension builds between the Italian-American owners of the pizzeria and the Black patrons in the community, a tension that eventually explodes into death and destruction.

Do the Right Thing’s main character, Mookie (played by Lee) works as a delivery boy for Sal’s Famous Pizzeria and as such, serves as a mediator of sorts between his White employers and the pizzeria’s Black patrons. When we meet him, he is wearing a white Brooklyn Dodgers home jersey with Jackie Robinson’s name and number 42 on the back. The jersey simultaneously marks Mookie as being on his home turf in Brooklyn, as well as referencing Robinson’s own home turf. Robinson and his wife Rachel stayed in a rented room at 526 MacDonough Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant during his trailblazing 1947 season.

Mookie’s Robinson jersey stands in opposition to the first of several Italian-American icons on the wall that director Lee reveals in a montage, Joe DiMaggio. According to W.J.T. Mitchell, the Wall of Fame functions as a kind of “exclusion from the public sphere” for the Black patrons, a reminder that in this space they are not equal citizens.3 Meanwhile, Mookie in his Robinson jersey foreshadows the tension that Lee would have Robinson embody in his screenplay: a symbol for racial tolerance on the surface, but with feelings of rage lurking just below the surface—rage that, when triggered, can easily overflow into violence. There were other, less consequential Robinson references in Spike Lee films, especially around the time he was working on his script for Jackie Robinson, including Malcolm X (1992), Crooklyn (1994), and Girl 6 (1996).

None of those references captured the imagination of the public the way his Instagram video did in 2020, announcing that he would be making his script available to the public. In the video, Lee sits in front of a poster from 1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story—an apt backdrop, because his story immediately situates itself against that film. The fifth draft of Jackie Robinson (1996) kicks off in the Robinsons’ living room in Stamford, Connecticut in 1972. Robinson, 53 and going blind, opts to go to bed instead of sitting with Rachel for a television screening of the 1950 film. “That story should be burned,” he says, heading upstairs and leaving Rachel alone to watch by herself.4 By focusing on Rachel’s experience of the old movie in the absence of her husband, Lee establishes two things: that his depiction of Robinson’s life will at least in part be seen through Rachel’s eyes; and that it will self-consciously critique the icon’s other cultural representations, particularly the first and, at that time, last major motion picture that had been made about Robinson—the 1950 film, starring Robinson as himself.

Rachel chose Lee to spearhead the biopic in October of 1994 despite widespread belief at the time that she would bestow documentarian Ken Burns with the opportunity.5 “I still feel that a black man can understand another black man and all the nuances of his life better than anyone else can,” she said at the time.6 But Rachel and her hand-picked filmmaker had different priorities in rendering Robinson’s icon. Rachel long fought the idea that he was an angry man—and to be sure, there is a tendency to portray Black men who are assertive and aggressive as dangerous and angry—but there has been a countervailing tendency to neuter Robinson of his anger—to make his story safe for White audiences and to make Robinson nonthreatening, which was Lee’s concern.

His script seems intent on upending an image of the hero, put forth in the 1950 biopic, as overly timid. When the bus of his barnstorming Negro League team stops at a rest stop somewhere in the South in The Jackie Robinson Story, Robinson is tasked with going in and getting sandwiches. Sheepishly, he walks in and is rebuffed by the man behind the counter. Robinson hems and haws until a White chef offers to make the players beef and ham and egg sandwiches. Robinson is his most courageous when he deigns to ask, “How about some fried potatoes on the side, chef?” Lee totally turns the episode on its head having Robinson’s Negro League manager, Frank Duncan, politely inquiring. When he is rebuffed, Lee’s Robinson insists that the team refuse to fuel up their bus at the establishment, a gesture that Lee tells us has earned a new “respect for the rookie college boy.”7

Robinson’s timidity in The Jackie Robinson Story is likely the byproduct of its attempt to cast Rickey, its White hero, in the most courageous light. When a petition begins to circulate among some of the Dodgers, opposing Robinson joining the club, the 1950 film focuses on the anger it rouses in Rickey. “You call yourselves Americans?” he admonishes the signers of the petition. When a local ordinance forbids an integrated Dodgers/Royals exhibition during spring training, an oddly contrite Robinson says to Rickey “I’m the cause of the trouble, Mr. Rickey. Maybe you’d like to call it off?” Rickey rebukes him, “Not on your life, boy! We started this together and we’ll finish it together!” In contrast, when Lee’s Robinson (up against not only bureaucracy but real hate) is confronted by a segregation-enforcing sheriff who literally shows up in a cloud of dust that Robinson kicks up sliding into home plate—he follows his manager’s orders to get off the field, but still manages to get in the last word: “Ok, Skipper, tell him that ah’ma gittin’.”8

That Lee emphasizes Robinson’s aggression doesn’t prevent him from also showing his vulnerabilities. He goes to great lengths to chronicle Robinson’s travails in the International League with the Montreal Royals: his stress-induced nausea, exhaustion, and efforts simply to have bat meet ball. The Jackie Robinson Story focuses on the challenges imposed upon Rickey. He has to fend off International League President Frank Shaughnessy’s last-ditch effort to pressure Rickey into re-thinking his great experiment. As for Robinson, he confesses to Rachel to being a “little nervous, maybe,” but given what Shaughnessy has told Rickey about the calamities that are about to befall the league, Robinson seems less courageous than naïve.

Even when Montreal heads (presumably) to Louisville in The Jackie Robinson Story, it’s unclear how the boos cascading from the stands affect Robinson. When a trio of White racists calling themselves “the welcoming committee” confront him outside the Royals locker room, it is Rickey (not even present!) who is center stage as we hear his words “you can’t fight back” echoing in Robinson’s mind—just long enough until his (White) Royals teammates can arrive and diffuse the situation. Back on the field, the film transitions to a montage of racist fans and opposing players and coaches hurling epithets at him. Some White fans taunt him with a black cat who he invites into the dugout and cuddles. He’s called a “shine” and a “sambo” and mocked by an opposing coach chomping on a giant piece of watermelon, but the film cross-cuts into dissolves not just to Robinson, but to his (formerly?) racist manager Clay Hopper, being won over to Robinson’s cause.

In Lee’s script, the watermelon incident (not mentioned in his memoir) happens in the majors when the Dodgers meet the Phillies in Ebbets Field in 1947. In a scene since immortalized in Brian Helgeland’s 42, Lee has Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman lay into Robinson with the most hateful, racist torments of the entire screenplay. As Robinson walks to the plate, the Phillies players hold up watermelons as Chapman hollers “Hey n_____, hey, n_____, you want a cold slice of watermelon?”9 The over-the-top, almost caricatured racism of the insults hurled at Robinson feels like the quick-cutting montage of racist slurs in Do the Right Thing and both have a similar effect: simultaneously demonstrating their absurdity and their cruelty.10

Just as it’s hard to separate Do the Right Thing from Lee’s Robinson screenplay when thinking about the writer/director’s use of racist slurs, it is difficult not to imagine his image of Robinson holding a baseball bat and not think about Do the Right Thing’s Sal brandishing a bat as a weapon. In Lee’s 1989 film, the bat was an overt reference to the murder of Michael Griffith, who in 1986, was beaten with a baseball bat by a group of White youths outside a pizza parlor in Howard Beach in Queens and then chased onto a highway where he was fatally struck by a car.

Perhaps more subtle is a visual cue he slips into his Jackie Robinson script when the Dodgers lose the 1947 World Series to the New York Yankees— the image of Joe DiMaggio, whose icon was the first Lee revealed in his “Wall of Fame” montage in Do the Right Thing. Going back to W.J.T. Mitchell’s notion that the display inside Sal’s Pizzeria functioned as a kind of “exclusion from the public sphere” for its Black patrons, the image of DiMaggio (first in the montage and in the center of the Wall of Fame) makes it resonate even more bitterly when it is revealed in Jackie Robinson at the precise moment when the Dodgers are denied a world championship. In this sense, DiMaggio’s image isn’t just a symbol of Dodger defeat, but an incitement of sorts—that in New York City, the integrated Dodgers are still not the equals of the lilywhite Yankees.11 The image of DiMaggio is the perfect pivot point in the script for Robinson’s evolution in Lee’s story. Not long after he has Branch Rickey visit Robinson in his hotel room to tell he no longer needs to turn the other cheek, that it’s time to “fight back.”12

In a scene in Lee’s script based on a moment in I Never Had It Made, Robinson confesses that the abuse out of the Phillies dugout drove him to think, “To hell with the image of the patient black freak I was supposed to create. I could throw down my bat, stride over to the Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist.”13 Lee’s Robinson doesn’t throw down his bat, but rather, charges into the Philadelphia dugout with his Louisville Slugger. He smashes the Phillies players who Lee depicts, screaming in pain. Then, he has Robinson smash Chapman in the mouth, leaving the Philadelphia manager “out cold, bloody and down for the count.”14 When Lee cuts back to Robinson stepping back into the batter’s box, his violent fantasy having ended, we have a heightened understanding of the strain he is under, and are less willing to take his peacefulness for granted, or to dare to think of it as “timidity.”

Part of what that meant for Lee was exercising the license to paint a complex picture of Robinson. The Robinson of The Jackie Robinson Story is Rickey’s obedient, suffering servant being sent to be crucified. We are given no window into his inner turmoil— that, as he tells us in his memoir, “I couldn’t sleep and often couldn’t eat. Rachel was worried, and we sought the advice of a doctor who was afraid I was going to have a nervous breakdown.”15 In Lee’s script, Rachel worries as the Phillies shout racist expletives because “she knows her husband could easily snap.”16

Lee’s Robinson is all too human and as such possesses faults. At times, he really is timid. He is afraid to ask Branch Rickey for a raise17 and to stand up for himself with Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley.18 Other times, he’s bull-headed. He pushes a fatigued Don Newcombe back to the mound in the ninth inning of the deciding playoff game against the Giants in 1951, causing the Dodgers 4-0 lead to be split in half.19 Bullheadedness is also framed as the reason he can’t bring himself into backing John F. Kennedy for president after he claims Kennedy can’t “look him in the eye.”20 Lee’s Robinson goes so far as to acknowledge his prideful mistake. Lee has him share via voiceover: “I do not consider my decision to back Richard Nixon over John F. Kennedy for the Presidency in 1960 one of my finer ones.”21

Most of all, Lee suggests that Robinson’s biggest flaw was his impatience. When Jackie, Jr. is 11, Robinson grows impatient with his son’s lack of baseball aptitude. He scolds him when he swings and misses at an underhand pitch, “How can you miss that?”22 And his zealous crusade for integration and incremental change (no matter how small) sometimes seems shortsighted, as does his insistence at staying at the Chase Hotel in St. Louis even though management still refuses to allow Blacks to enter its dining room, night club, or swimming pool. “Why give them white folks my money when I can’t get the same privileges as the next man?,” asks Roy Campanella. “We’re patronizing black businesses,” adds Don Newcombe.23

Though Robinson’s impatience also seems to be an occasional virtue. In a line cribbed straight from I Never Had It Made, he has Robinson say of his decision to steal home in Game One of the 1955 World Series: “I took off. I really didn’t care whether I made it or not. I was just tired of waiting.” And just as his zealous impatience produced a momentum shift in the World Series, so too does it produce an unexpected outcome at the Chase. Newcombe ends up joining Robinson at the hotel and the two even gain entry to the hotel dining room.24

Lee’s biopic also presents more complex views of racism than previous films about Robinson. Dodgers teammate Hugh Casey flippantly tells Robinson that when he was down in Georgia having bad luck at poker, he’d rub “the teat of the biggest, blackest n__ woman I could find.’ In Lee’s description of the action, the screenwriter pauses to editorialize, “AHHH SHIT!!!!!” though Robinson, the character, doesn’t find any humor in the slipup. He tells Wendell Smith: “Do you have any idea what it took on my part not to kill that cracker?”25 But Lee cleverly distinguishes Casey’s casual racism from the willful and sadistic strain belonging to Ben Chapman. It is not the obvious White allies (Pee Wee Reese or Ralph Branca) who Lee has rush to Robinson’s defense when Enos Slaughter spikes him in St. Louis, but Casey who only moments earlier had uttered a racist epithet.26 The effect is not to diminish the significance of Casey’s bigotry, but to show a more complicated (and perhaps more modern) version of racism at work—one not necessarily reducible to willful, discriminatory hatred.

Lee’s characterization of Leo Durocher also explores this idea. Lee introduces him as a character during spring training prior to the 1947 season when the infamous petition is circulating, and the Dodgers manager is irate. He scolds his players, “I don’t care if the guy is yellow or black or if he has stripes like a fuckin’ zebra, I’m the manager and I say he plays.”27 But Durocher’s egalitarian spirit is nowhere to be found when supporting Robinson is no longer in his interest. We meet him again in 1951 during the Dodgers’ three-game series with the New York Giants who he is now managing. Pulling aside Black players Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, and Ray Noble in the Giant’s clubhouse, he warns his players that “if the game gets close into the late innings I may be shouting n____ and watermelon at the guys on other side like Robinson.”28

Lee never secured financing for his Jackie Robinson script, claiming that he had wanted Denzel Washington to play the role of Robinson but that the then-42-year-old actor thought he was too old. The truth is a little more complicated. When Lee wrote the script, his power in the industry was waning. After a disappointing $48 million at the box office for Malcolm X (1992), ticket sales for his films followed a general downward trend. Crooklyn (1994) made only $14 million against a $14 million budget. Clockers (1995) generated $13 million domestic gross from a $25 million budget, and Girl 6, released the same year that Lee finished the fifth draft of his Robinson screenplay, earned a paltry $4.9 million against a $12 million budget. Without Denzel Washington in the starring role, few were willing to provide the $40 million budget Lee wanted for production.29

It’s a shame because, even more so than Malcolm X, Lee seems comfortable channeling Robinson’s voice. He explores the unspoken class tensions between Robinson and his Kansas City Monarch teammates. Satchel Paige tells Robinson to go back to “U.C. of the L.A.” for “some mo’ schoolin’”30 and calls him “college boy.”31 When Lee’s Wendell Smith calls up Robinson to ask him to venture to Boston for the tryout with the Red Sox in 1945 he tells him, “We need players of your background and ability.”32 When Robinson meets Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams neither of them speak with the Black dialect in which Lee had the Negro Leaguers speak. Nor does John Wright, the African-American pitcher who joined Robinson at spring training in Daytona Beach, Florida prior to his season with Montreal. When Branch Rickey Jr. steps to the microphone at the press conference announcing Robinson’s signing by the Montreal Royals he characterizes Robinson as “a fine type of young man, intelligent, and college bred…”33 When Paige hears the news he bemoans that “I should have been the one” and that “it’s just because Jackie has an education [that he was chosen].”34

The idea that Robinson was or wasn’t fit to represent the Black people because of his middle-class status is an idea that Lee was particularly in touch with. During the leadup to Malcolm X, a rally was held in Harlem in an attempt to urge Lee not to “mess up Malcolm’s life.” According to the poet Amiri Baraka who had a hand in leading the protest, “We will not let Malcolm X’s life be trashed to make middle-class Negroes sleep easier.”35

It should perhaps come as little surprise that Lee shows Robinson being booed in Harlem by a crowd of “afros, dashikis and raised clinched fists.”36 Robinson’s passion for incrementalism which inspired him to endure taunts, attacks, and injustices is precisely what gets called into question. Lee’s Robinson defends Nelson Rockefeller’s efforts to build a Harlem State Building, “Maybe this isn’t the best thing in the world, but it’s something” as a new generation of activists accuse him of being a “sellout” and an “Uncle Tom.”37

Balancing out (or perhaps cancelling out) the critique of Robinson as “sellout” is the idea that he was too controversial, too ideological, too strident— paradoxical claims that have also been leveled at Lee. In the script, Robinson uses the New York Daily News columnist Dick Young to articulate a view sometimes referred to today as “shut up and dribble.” He contrasts Robinson’s frosty relationship with the media with that of his teammate, Roy Campanella. “A lot of newspapermen are saying that Campy’s the kind of guy they can like but that your aggressiveness, you’re wearing your race on your sleeve, makes enemies,” he informs Robinson.38

The Jackie Robinson Story (1950) ends with Robinson approaching Rickey in the dugout after the Dodgers have won the pennant and asking whether he should accept an invitation to Washington to speak to the American people about Democracy and, in Rickey’s words, “about a threat to peace that’s on everybody’s mind.” After testifying that “Democracy works for those who are willing to fight for it,” the camera dissolves to a shot of the Statue of Liberty and the score swells into rendition of “America the Beautiful.” The White narrator then proclaims: “Yes, this is the Jackie Robinson story, but it is not his story alone, not his victory alone. It is one that each of us shares…”

Spike Lee’s Robinson script ends with Robinson proclaiming that he cannot stand and sing the American anthem or salute the flag knowing that he is a Black man in a White world. The script not only re-situates Robinson as the hero of his own story, renders him a complex three-dimensional person, and paints a picture of a great experiment that was tense, combustible and far from a sure thing. It also gives a greater sense of what his experience means to the Black community.

Until the Dodgers pennant-winning game in 1947 that is the climax of The Jackie Robinson Story, Rachel is the only African-American represented in the stands. (And even in that pennant-winning game, the lone additions to Rachel are Robinson’s brother Mack, mother Mallie, and a random Black couple who are there for the payoff on a joke about a formerly racist fan being won over by Robinson.) Lee, meanwhile, goes to great length to show the impact that Robinson is having on the Black community—the hundreds of cops enforcing racial quotas at the gates of the stadiums in which he plays, turning away large numbers of Black fans who understand that Rickey’s “great experiment” is theirs as much as it is his.

Lee never got to make his Robinson film, but he was able to make a three-minute short film for Budweiser called Impact, celebrating Robinson’s 100th birthday in 2019. Cutting between a bar filled with Black patrons listening to his first major-league at-bat on the radio and a contemporary naturalization ceremony in which immigrants (including a woman in a Robinson jersey) are taking an oath of allegiance to the country, and narrated by Robinson’s daughter Sharon, the film ends with a montage of 11 contemporary activists who presumably had been touched by his “everlasting impact.”39

Not to minimize the courage it took for Budweiser to connect Robinson’s legacy with immigration at the height of then-President Donald Trump’s attack against those coming to the U.S. to seek a better life, but there is a certain irony to Spike Lee so thoroughly universalizing Robinson’s story after struggling for years to make a film that once and for all captured a particular experience that would be grounded in blackness. “Like a ball hit just right,” Sharon Robinson narrates, “he sent us on an irreversible trajectory, reminding us all that not only baseball but that life itself is a game of impact.” In the midst of a montage of Robinson artifacts, there is a brief shot of Lee costumed as Mookie on the streets of Bed Stuy: staring straight at us, arms crossed. At first it feels like he’s there to stand in judgment of its own inclusion, but he’s also there in tacit recognition that Robinson’s “impact” today, at least in part, emerges from contemporary conversations about his meaning. Though Spike Lee never got to make his Robinson biopic, he is still very much part of those conversations.

JOSHUA NEUMAN is a writer and producer whose work has appeared in Slate, Esquire, Vice, Los Angeles Magazine, Victory Journal, and Heeb (which he edited for nearly a decade). He is currently working on a book about former owners of the L.A. Rams, Carroll Rosenbloom and Georgia Frontiere.

Notes

1 Ryan Lattanzio, “Spike Lee Shares Script for Unmade Jackie Robinson Passion Project – Read Now,” IndieWire.com, March 29, 2020. https://www.indiewire.com/2020/03/spike-lee-jackie-robinsonscript-1202221317/, Accessed December 20, 2021.

2 Spike Lee as told to Kaleem Aftab, That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2005), 174.

3 W.J.T. Mitchell, “The Violence of Public Art: Do the Right Thing,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 16, no. 4 (1990): 894.

4 Lee, 3.

5 William C. Rhoden, “Jackie Robinson, Warrior Hero, Through Spike Lee’s Lens,” New York Times, October 30, 1994. Lens, https://www.nytimes.com/1994/10/30/sports/sports-of-the-times-jackie-robinsonwarrior-hero-through-spike-lee-s-lens.html Accessed December 20, 2021.

6 Rhoden, “Jackie Robinson, Warrior Hero, Through Spike Lee’s Lens.”

7 Lee, 23.

8 Lee, 51.

9 Lee, 73.

10 Do the Right Thing movie clip, https://youtu.be/gLYTObRhcSY

11 Spike Lee, Jackie Robinson, unpublished manuscript, 1986: 85.

12 Lee, 86.

13 Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had it Made (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 59.

14 Lee, 74.

15 Robinson, 49.

16 Lee, 73.

17 Lee, 90.

18 Lee, 103.

19 Lee, 98.

20 Lee, 130.

21 Lee, 129.

22 Lee, 117.

23 Lee, 110.

24 Lee, 112.

25 Lee, 79.

26 Lee, 83.

27 Lee, 66-67.

28 Lee, 95.

29 Lee as told to Aftab, 211.

30 Lee, 16-17.

31 Lee, 18.

32 Lee, 19.

33 Lee, 36.

34 Lee, 36.

35 Evelyn Nieves, “Malcolm X: Firestorm Over A Film Script,” New York Times, August 9, 1991: B1. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/08/09/nyregion/malcolm-x-firestorm-over-a-film-script.html Accessed December 20,2021.

36 Lee, 136.

37 Lee, 136.

38 Lee, 106.

39 Budweiser ad clip, https://youtu.be/KBvNSznpg0s?t=146