Cap’s Bats: The Baseball Bats of Captain Adrian C. Anson

This article was written by Robert H. Schaefer

This article was published in 2003 Baseball Research Journal

Adrian C. Anson was the venerable captain of the famous Chicago White Stockings when they were the kingpins of the baseball world in the 1880s. Anson is more popularly, although slightly incorrectly, known to today’s fans as “Cap.” In his own time, Anson was identified in the press, variously, as “Ans,” “The Big Swede,” and “Baby.” It wasn’t until 1879, when he was appointed captain and manager of the Chicago Nine, that his name appeared in print prefaced by “Captain,” and sometimes “Capt.” but almost never as “Cap.” True, players of that day normally addressed the team captain as “Cap,” but that was a familiarity not usually taken by the reporters. In the last stages of his 26-year career, Anson was known as “Uncle Anson,” “Your Uncle,” “Pop,” “The Old Man,” and finally after he retired in 1897, “The Grand Old Man.” Incidentally, his wife called him “Pop.”

One of Uncle Anson’s many claims to fame is as a hitter. He was the first major league hitter to collect more than 3,000 base hits, including those he accumulated in the National Association. This was despite the fact that during his career the schedule never approached·154 games per season. Between the years 1871 to 1897, Anson participated in a low of 29 games (1871) and a high of 134 games (1889) for a grand total of 2,523. Anson played 247 games in the Association and 2,276 in the League.

Players of the 19th century indulged themselves in an abundance of superstitions. Many players named their bats, and some, notably Pete Browning, believed that each bat contained only a given number of hits. Once all the hits had been knocked out of the bat, you might as well throw it away. A hitter knew exactly when he had exhausted the quota of hits in any given bat — because the base hits just stopped coming. It was a sure sign you needed to change your bat. And that is just what many players did.

But instead of putting the now hitless bat in the trash, hitters who held such mystical beliefs, such as Browning and Anson, retired it with honor to their basements and preserved it. Anson treated his bats with awe and reverence that bordered on superstitious behavior. A bat was not just an inanimate hunk of wood. No, it was a living entity that had to be treated with respect if it was to do its intended work — lining out base hits on a regular basis.

The size and weight of bats in Anson’s time were unique to that period. Following his career as a brilliant hitter George Sisler became a very effective hitting instructor. In addition to performing this service for several major league clubs, Sisler wrote detailed instructional booklets on the art and science of hitting. In 1935 he made the following comparison of bats of that day to bats of the past:

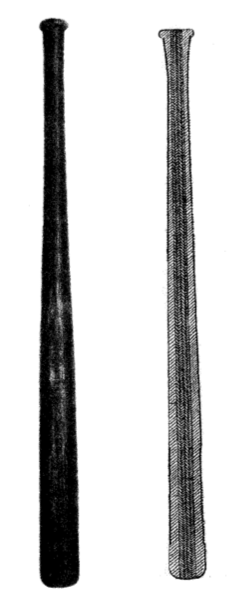

“Have you ever seen specimens of the bats used in the early days of baseball? Veritable wagon tongues they were, not much longer than modem bats but much heavier and much thicker in the handles. The bat used by Pop Anson, whose record, as a leading batsman, almost equals that of Ty Cobb, was 36 inches long and weight 48 ounces and its handle had a circumference of 4 inches.”

John Phillips, in The Riotous 1896 Cleveland Spiders, provides this description of Anson’s bat:

“Tacks Parrott of the Browns uses the longest bat in the League. Uncle Anson, of course, uses the heaviest. Ans says it’s easier to place hits with heavy bats than with light ones. He knows what he’s talking about. His bat is made of hickory and could be broken only by a rock crusher. Nobody would ever steal it because nobody else could swing it.”

On July 9, 1884, The Sporting Life published the following report on what was reputedly a revolutionary technique in bat design and construction:

Anson’s New Bat – Something New

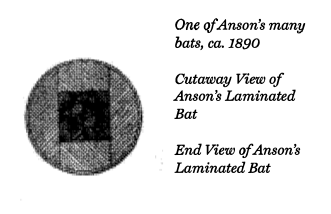

A Bat Which is Calculated to Flatten Batting AveragesCaptain Anson in the game of the 23rd made a trial of a new style of bat just made as an experiment. The bat is made of several pieces of ash, jointed and glued together lengthwise, while in the center is inserted a rattan rod about one inch square, and composed of twelve strips of rattan firmly glued together, running from end to end of the bat. The handle is wound with linen cord. This wrapping of the handle, however, is technically a violation of the rule, which requires the bat to be made “wholly of wood,” but it is a rule which nobody will object to changing if the wound handle proves to be an improvement. The object of the glue joints and the rattan rod in the center is to make the bat less liable to break and at the same time to give it more spring. That both of these objects are accomplished there can be no doubt. The first ball hit by Anson with the new bat was a terrific liner to left field for two bases, and he used it throughout the game with great success, Captain Morrill having agreed to waive any objection to the wrapping of the handle. Heretofore bats have been made of a single stick, and the improvement adds materially to the expense of manufacture. Players who have tried it say that the ball can be driven 25% farther by the exercise of equal force than the common bat. Anson certainly made a remarkable record in the two games in which he used it. On June 23, Buffington pitcher, in three times at bat he made a single and a double; on June 24, Whitney pitcher, four times at bat, two singles, one double, and a home run. The cost of the new bat will be about $5 each.

The premium wooden bats of 1884 cost from $1.00 to $1.25 each, so the proposed cost of Anson’s new bat, five dollars, was extremely high. The matter of wrapping the handle with linen cord was but a trifle to deal with. In 1885 the rules were amended to allow the bat to be wound with twine for a distance of 18 inches from its end so that objection disappeared.

An interesting aspect of Anson’s “new” bat of 1884 is that it wasn’t really a “new” concept. Henry Chadwick, of the New York Clipper, reported on May 3, 1874, that he was shown a new type of bat at George Wright’s sporting goods store in Boston. This bat was made with a cane fitted through the whole length of the bat. The purpose of this cane was two-fold: to prevent the bat from breaking, and to impart elasticity, which drives the ball farther. It was claimed that the bat would last the entire season. The bat only weighed thirty-two ounces, extremely light for the time. It was also very expensive, costing $4.00. Wright’s bat of 1874 sounds almost identical to Anson’s bat of 1884.

Specific follow-up reports of George Wright’s bat being used in games, or subsequent use of Anson’s similar bat of 1884, have not been uncovered at the present time. The rule governing bat design in 1884 simply stated that the bat was to be made wholly of wood so that both Wright’s bat and Anson’s bat were in compliance. It wasn’t until 1940 that the rule governing bat construction was amended to specify, “The bat must be made entirely of hardwood in one piece.” Clearly, Anson’s bat met all the applicable rules of 1884.

A discussion on the use of multi-wood bat construction appeared in the Spalding Official Base Ball Guide for 1925, long after Anson’s time in baseball. The 1925 guide included an article about Jack Pickett, who had passed away in Chicago during the summer of 1922. Pickett had been the chief bat designer for the Spalding factory, and it was claimed that he had designed more baseball bats than any other man in the world.

“The heaviest bat that Pickett ever put together was one that was used by Anson, and those who recall Anson in his prime will also remember that the bat which he took to the plate with him was left severely alone by the other players. They couldn’t swing it. Anson had a core of hickory in the bat and over it was split bamboo, or occasionally ash. The bat was so heavy that players who were fast swingers with light sticks could not get Anson’s hardwood war club around in time to meet the ball.”

From this account, it is reasonable to infer that Anson used bats of laminated construction throughout his career, although not exclusively, as he used many bats of traditional design, and fashioned from a single piece of hardwood.

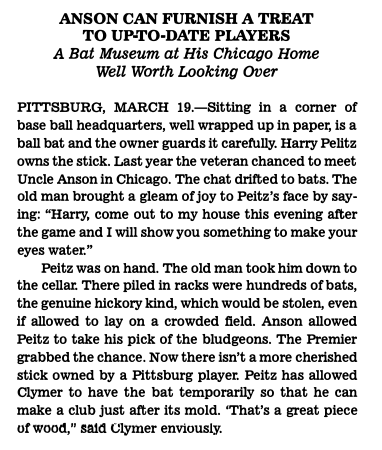

Pop was continually experimenting in an attempt to find the perfect piece of lumber with which to sting the ball. Legend has it that he would drive his horse drawn rig throughout the countryside, keeping a sharp eye peeled for candidate lumber that was properly seasoned. Sometimes an old fence post caught his fancy; other times he became enamored of a fallen log or a stump. Anson would then strike a bargain with the farmer on whose land he discovered the raw material for his new bat, load the lumber into his rig, haul it home, and have it converted to a war club. Over the course of his 26-year career, Anson constantly changed bats, but he never disposed of a single one. Anson “retired” his bats to his basement.

On March 24, 1906, The Sporting Life carried the following report:

In a private letter now on file in the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown, NY, dated February 20, 1957, Jack Corbett1 of the Hollywood Star Base, tells this tale of Anson’s devotion to his lumber: “Anson had over 400 bats in his cellar when he quit playing. All were oiled and dusted every day except Sunday up until 1907. While we were playing poker at Cap’s home one evening [in 1907] Mrs. Anson told me that there would be a present for me outside one of the cellar windows when I left for home. There was — one of the Cap’s bats that he had sworn he would never part with.

“I took it to the old Spalding bat factory and Jack Pickett put it in a lathe and turned off just enough to make it look fresh. When I stepped out on the clubhouse porch with it Cap was sitting in the stands at least fifty yards off. He looked at me and then the stick – he got up and roared at me – “Where did you get that bat?” I told him I had swiped it out of the cellar and after kicking that around a little he said, ”Well, now that you have it, use it and be sure you get some hits with it.”

Corbett continued with his tale of Cap’s bats:

“When we later played Callahan I let Mike Donline use it. He showed it to Callahan and Jimmy got hold of the Cap and gave him $7.00 per bat for all he had.”

This evidently was the fate of the bats Anson had stored in his cellar. The Old Man must have been hard-pressed for money in order to sell his most cherished possessions in that manner.

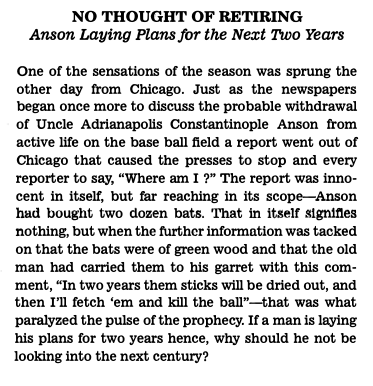

As Anson’s career wore on, speculation abounded each winter over when The Old Man would retire from the diamond. By 1893 Anson had achieved the ripe old age of 42, and more than half of the summers of his life had been spent in professional baseball. On February 5, The Sporting Life carried the following report:

Although Anson was forced into retirement at the end of the 1897 season, his legendary bats continued to do their work on the diamond well into the 20th century. On May 25, 1911, The Sporting News reported the current use of one of Anson’s bats:

“John Titus, the Philadelphia right fielder, is using a bat that has some history connected with it. In 1894 Captain Anson discovered a piece of timber that is considered ideal wood for a baseball bat and he proceeded to have it turned into a cudgel. Anson in his day merely had to swing it and the ball would go to the fence. It is so heavy, however, that many an ordinary player would hardly care to handle it. When Pop Anson retired from the game he retained this great stick as a treasure. At last, when the former star’s belongings went under the hammer Pat Moran purchased this bat, and when Pat was bought from the Cubs he brought it to Philadelphia. Titus coaxed and finally, Moran consented to let him have the bat. His first hit was a home run over the fence off Bob Harmon, of St. Louis. Titus has been batting consistently ever since he came into possession of Pop’s old lumber.”

John Titus played in 76 games in 1911 and posted a .284 batting average, not much over his .282 lifetime mark. However, he achieved career highs for both slugging average and home runs. How much credit for this performance was due to Pop’s old bat?

BOB SCHAEFER is retired from the aerospace industry. He is a long-time contributor to SABR publications.

Notes

1 SABR member Daniel Ginsburg relates that Jack Corbett was a lifetime baseball man. He played in the minor leagues, as well as outlaw leagues, for 14 years, mostly during the Deadball Era. Later Corbett owned teams in Atlanta, Jersey City, Syracuse, and El Paso.