Career .300 Batting Averages

This article was written by Bob McConnell

This article was published in 2003 Baseball Research Journal

The magic number for a batting average is .300. When a player hits .300 or better, he has had a good season. A .299 average just doesn’t look as good. Many record books list players with a career average of .300, but they usually their lists to players with 1,000 or more hits. What about the .300 hitters with less than 1,000 hits? You would think that a player who can maintain a .300 average should be able to stick around long enough to accumulate 1,000 hits. Let us look at these in greater detail.

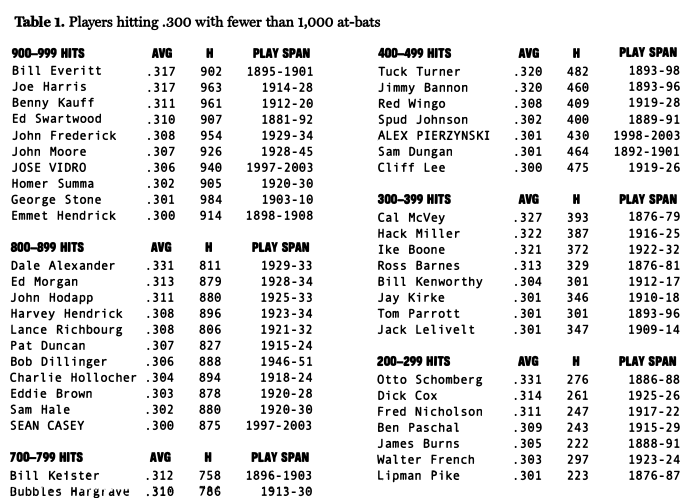

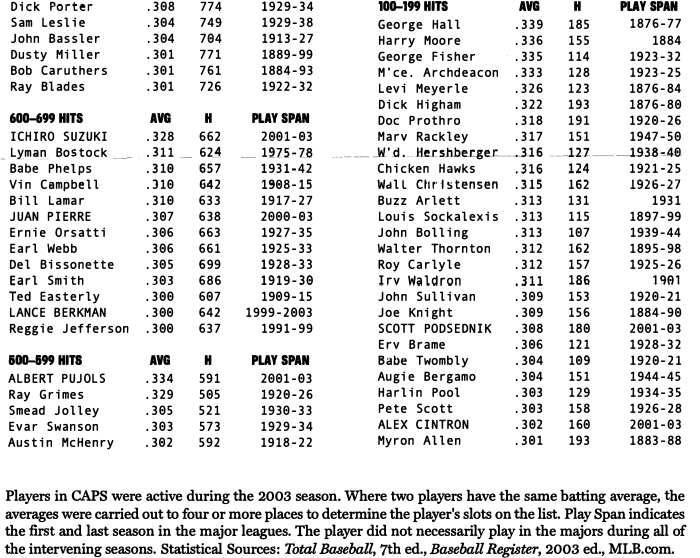

The following table is broken down into nine groups: from players with 900-999 hits down to players with 100-199 hits. Obviously, a player with 100 hits should not be bracketed with a player with over 900 hits.

(Click images to enlarge)

The best explanation for not sticking around is death. Three players died during their active major league careers. Austin McHenry died of a brain tumor shortly after the end of the 1922 season. Willard Hershberger, playing for the Cincinnati Reds, committed suicide in August 1940, while the Reds were making a successful run for the National League pennant. Lyman Bostock was killed in 1978 when he was accidentally shot while riding in a car. The shot was meant for one of the other passengers.

There are nine active players on the list; some of these players would go on to bang out 1,000 hits while maintaining a .300 average and thus get into the record books. Others would fall below .300 as their careers wound down. Duke Snider dropped from .300 to .295 during his last two seasons. Mickey Mantle slipped from .302 to .298 during his last season.

Six players — Ross Barnes, George Hall, Dick Higham, Cal McVey, Levi Meyerle, and Lipman Pike — played in the National League in 1876, Many historians consider this as the first major league season. All six of these players had played for five years in the National Association of 1871-75 and had played on independent clubs prior to that. Barnes had an overall average of .390 in the NA, Meyerle .365, McVey .362, and Pike .332. It can be said that the careers of these players were already on the way down. George Hall was banned from baseball after the 1877 season for throwing games.

For the 1887 season, bases on balls were counted as hits, which really inflated batting averages. Myron Allen, Bob Caruthers, Otto Schomberg, and Ed Swartwood all played in 1887, and they greatly benefited from this rule. By recalculating their career averages by taking away their hits as a result of bases on balls, the averages for all four players drop below .300 (Swartwood to .2994).

The Federal League of 1914-15 is listed in most baseball books as a major league. However, it was a notch below the other two major leagues of its time in the quality of play. Benny Kauff led the league in batting for both years of its existence with averages of .370 and .342. Benny was called the “Ty Cobb of the Federal League.” Without his Federal League numbers, Kauff’s major league average was .287. Ted Easterly and Bill Kenworthy would also slip below .300 without the benefit of their Federal League stats.

A fourth Federal Leaguer, Vin Campbell, is an interesting character. He played in the National League for several years prior to jumping to the FL. His overall average in the NL was .306. He had a good rookie year with Pittsburgh in 1910 but then quit to enter the brokerage business in St. Louis. He had a change of heart and rejoined Pittsburgh in the middle of the 1911 season. The Pirates traded him to the Boston Braves, and he had another good season in 1912. He refused to report in 1913, and it is not known how he spent that summer.

In 1914 he signed a three-year contract for $25,000 with the Indianapolis club in the Federal League. The club moved to Newark for the 1915 season, and the league folded before the 1916 campaign. As part of the peace agreement, Newark owner Harry Sinclair was allowed to sell many of his players to Organized Baseball Clubs. Campbell was sold to the St. Louis Browns in late February, but he never reported. Instead, he went into the auto business in Pittsburgh. He sued Sinclair for his 1916 salary and collected.

As all fans know, the level of play really dropped during World War II. Two players on the list played during the war. John Bolling hit .351 in 1944 after hitting .289 in 1939, his only other season in the majors. Augie Bergamo hit .286 in 1944 and .316 in 1945 for an overall average of .304 for his two major league seasons. Bob Dillinger had a very good season at Toledo (American Association) in 1942. He then spent the next three years in military service before going up to the St. Louis Browns in 1946. He surely would have garnered the 112 hits that he needed to push him over the 1,000 mark had it not been for the war. Joe Harris, with 963 hits, certainly would have reached the 1,000 level, but for the fact that he spent 1918 in military service.

There are four pitchers on the list. Three of them — Bob Caruthers, Tom Parrott, and Walter Thornton — played during the 19th century. Many pitchers in those days filled in as position players from time to time. This was the case with Caruthers, Parrot, and Thornton. However, they were getting paid to pitch, and their stay in the majors depended on how well they performed on the mound. Caruthers did stick around long enough to win 218 games. Erv Brame, the fourth pitcher, played in the 20th century and was used only as a pitcher.

Catchers do get into many more games than pitchers, but still not as many as other position players. Two catchers on the list — Willard Hershberger and Ted Easterly — have already been mentioned. Four additional catchers — John Bassler, Bubbles Hargrave, Babe Phelps, and Earl Smith — all played for at least nine years in the majors. They just didn’t get into enough games to reach the 1,000 mark.

Three all-time minor league greats — Buzz Arlett, Ike Boone, and Smead Jolley — had brief stays in the majors. Arlett had a minor league career batting aver age of .341 with 2,726 hits, 598 doubles, 432 homers, and 1,786 RBI. Boone hit .370 with 2,521 hits, 477 doubles, 128 triples, 217 homers, and 1,334 RBI. Jolley hit .366 with 3,037 hits, 636 doubles, 336 homers, and 1,593 RBI.

These players were stuck with the good-hit, no-field label. It is hard to imagine them being that bad as fielders. After all, Zeke Bonura (who was a notoriously poor fielder) lasted long enough in the majors to collect 1,000 hits. Dick Porter spent eight years with Baltimore of the International League (1921-28) before reaching the majors. During that period, Baltimore players were not subject to the major league draft and the club held back a number of good players. Other players who, for some reason, took a long time to reach the majors were Eddie Brown, John Frederick, Ben Paschal, Lance Richbourg, and Earl Webb.

Jay Kirke was an interesting and, some say, eccentric person. He played for Joe McCarthy in Louisville and Joe loved to tell funny stories about him. Kirke played in the minors for 21+ years in addition to one full season and parts of six others in the majors. An anonymous quote might explain one reason why Kirke didn’t stay longer: “He can hit, but as a fielder, he can only retrieve.”

Emmet Hendrick quit baseball to go to work on the railroad. By coincidence, his brother was the president of the railroad. Could there have been a salary increase involved?

A number of other players on the list had long and successful minor-league careers. Were they all bad fielders? Among other long-time minor league players on the list are Jim Bannon, Del Bissonette, Pat Duncan, George Fisher, Bill Keister, Bill Lamar, Cliff Lee, Jack Lelivelt, Fred Nicholson, and Babe Twombly. Was Keister a bad fielder?; the answer is yes. Bill holds the major league record for lowest fielding average for a shortstop in 100 games or more games with a mark of .861. Playing for Baltimore in 1901, he made 88 errors in 114 games.

Maurice Archdeacon is another interesting story. Ty Cobb had scouted him and reported that he would never hit in the majors. However, the White Sox paid a hefty price for him. He went up to the Sox in late 1923 and hit .401 in 22 games. Johnny Mostil beat him out of the center field job the following year but missed a number of games due to illness and injuries. This gave Archdeacon playing time, and by August 1 he was hitting .386. His career average at that point was .391, possibly the best start for any player in history. But that was his high point. He hit .185 for the balance of his major league career, and the White Sox practically gave him to Baltimore in early 1925. Archdeacon’s main asset was speed, although he was not a great base stealer. He beat out many grounders, and infielders probably would have learned how to play him.

Then there are those players who were asked the question, ”Yeah, but what have you done recently?” These players started their major league careers strongly but slumped during their last year or two and earned a one-way ticket back to the minors. Tuck Turner hit .418 in his second season in the majors. He hit .243, .291, and .199 in his last three seasons. Other players who had a poor final season were Charlie Hollocher, Sam Leslie, Dusty Miller, Ed Morgan, Fred Nicholson, Ernie Orsatti, Harlan Poole, and George Stone. Hollocher missed a great deal of time due to various illnesses. He had a reputation of being a hypochondriac and he eventually committed suicide.

Louis Sockalexis (what a great name for a slugger) is a sad case. He was a Penobscot Indian from Old Town, Maine, and he starred in baseball at Holy Cross College. With much fanfare, he went directly to the majors with Cleveland in 1897. He proceeded to hit .338 in 66 games. He soon began to drink heavily. The club put up with his problem for two more years but finally had to let him go. He died at the early age of 42.

Harry Moore was a mystery player until recently. He played a full schedule for Washington in the Union Association of 1884. Yet the record books have no biographical data on him. Two researchers have been working on him and have uncovered a great deal of information. His correct name is Henry Scott Moore and he was born around 1862 in California, probably in San Francisco, where he spent his early childhood. He started his pro career with Reading of the Interstate Association in 1883. After his stint with Washington in 1884, he played for Washington and Norfolk of the Eastern League in 1885. Other stops in the minors were at Atlanta, Topeka, Sacramento, Stockton, and San Francisco.

Cuckoo Christensen and Glass Arm Brown made the list. Is there any connection between their nicknames and the fact that they didn’t last long in the majors?

The following are interesting bits of information about players on the list:

- Tuck Turner played in the great Philadelphia out field of 1894 (Turner .418, Sam Thompson .415, Ed Delahanty .404, Billy Hamilton .403).

- Red Wingo, the brother of Ivy, played a career-high 130 games in the Detroit Tigers outfield of 1925 (Harry Heilmann .393, Ty Cobb .378, Wingo .370, Bob Fothergill .353).

- Ross Barnes led the NL in batting in 1876, George Stone led the AL in 1906, Benny Kauff led the FL in 1914 and 1915, Bubbles Hargrave led the NL in 1926, and Dale Alexander led the AL in 1932.

- Pat Duncan was one of the stars of the 1919 World Series, and Joe Harris starred in the 1925 Series.

- Oscar Ray Grimes had a twin brother, Roy, who played in the majors. His son Oscar Jr. also played in the majors.

- Earl Webb holds the major league record for most doubles in a season with 67, set in 1931.

There are, no doubt, stories to be told about the other players on the list. Maybe SABR members can dig up some of them.

BOB MCCONNELL lives in Wilmington, Delaware, and is a founding member of SABR. He was the first recipient of the Bob Davids Award, SABR’s highest honor.