Carl Hubbell’s 24 Straight Victories in 1936-37

This article was written by George Bulkley

This article was published in 1983 Baseball Research Journal

Old Rube Marquard (he was 90 when he went to his last reward) was firmly convinced that the record keepers had it all wrong. The way he saw it he won 20 straight games in 1912, not the 19 he is credited with in all the books. And Rube could, on occasion, be quite persuasive. More than one sportswriter, looking for a fresh angle, took up the Rube’s cause in print.

Alas, to no avail. Keepers of the records from the first held that Marquard had no case. It was true, they admitted, that under present scoring rules he had a point. But, they hurried to add, Marquard won his games in 1912, not today, and under the rules of 1912, he won only 19 straight.

Marquard may have gained some satisfaction when early researchers discovered he really had won 20 straight by reason of a victory in his last 1911 game, but this feeling suffered somewhat when another New York Giant southpaw came along in the next generation who put together an undisputed chain of 24 wins over a two-year period. That would be Carl Hubbell, and there is no gainsaying he screw-balled his way to a record that, as is said about too many records, may well last forever.

But to start at the usual place – the beginning – 1936 was an unusual year as far as the Giants were concerned. World’s champions in 1933 and late season goof-ups in the next two seasons, they began 1936 as though winning was as bad as stealing.

Something was wrong with the club, and there were some unkind enough to say that everything was wrong with it. Their pitching staff was a shambles. Slick Castleman couldn’t get started. Schumacher’s arm was ailing. Veteran Fred Fitzsimmons just wasn’t ready. Frank Gabler was a risk. Hubbell was overworked, although he had managed ten wins against six losses. The promising Al Smith had his bad days.

But it was more than pitching. The aging Travis Jackson had a bad knee and was covering fully as much ground as his shadow. Dick Bartell at shortstop was making wild heaves past first base. Burgess Whitehead wasn’t hitting. Sam Leslie was lumbering around first base on damaged legs. Mel Ott and Joe Moore, the old reliables, had both fallen into hitting slumps. Manager Bill Terry had to drag his battered frame out on the diamond. Their defense, to sum it up, was as full of holes as a carload of Swiss cheese.

It was a time of disaster. Strategy was a dirty word. If Terry made a move it was sure to be a big help to the ball club — the ball club the Giants happened to be playing. If a Giant made a hit, it was with two out and nobody but the coaches near the bases. If a Giant made an error it was just in time to hand the other gents the ball game. Terry was on the grill and his critics were building a gorgeous bonfire under him.

Giant fans surely were not optimistic over their team’s chances when they opened their July 17 newspapers to find the club bogged down in fifth place with an uninspiring 42-41 record, 10-1/2 games back of league-leading Chicago. The low point in the season’s fortune seemed to come in Hubbell’s last defeat of the season. Playing in Chicago on July 13th (not a Friday, but a Monday) when Carl held the home team to two measly singles yet lost a 1-0 game when Whitehead made a throw that was both ill-advised and far over Bartell’s head.

The New Yorkers moved on to Pittsburgh and, suddenly, everything was changed. Bill Swift started for Pittsburgh and headed for the showers within minutes as Moore, Ott and Hank Leiber unloaded three-baggers in the first inning. Brought on in relief, Big Jim Weaver was tagged for a fourth triple in the same inning by utility infielder Eddie Mayo. Hubbell, poised as a poplar, coasted to a 6-0 win. The fairy godmother had waved her wand and the mice turned into beautiful stallions.

It would be folly to claim that Carl Hubbell, alone, won the oennant that year for New York, but there can be no gainsaying he was a key factor; nay, more, he was THE key factor. As he swung into his 16-game winning streak the rest of the pitching staff braced. Game after game was won on strong pitching and timely hitting.

The defense stiffened. When a fielder made a circus catch it was just in time to save the ball game. Where Mancuso had been the only man who could make a hit when it counted, Ott, Moore and Ripple began slapping out the hits that brought in the runs at the right time. Bartell settled down to accurate pegging and hammered out a couple of homers when they did the most good. If a fielder made an error, he picked the proper time and made it when it didn’t count in the scoring.

Every managerial move Terry made turned out to be perfect strategy. He was once again the mastermind of 1933. Take the day the Giants bounded over the Cardinals to the top. Terry put Leiber in and he delivered the blow that won the game. Bill took Leiber out and inserted George Davis for his fielding. George saved the game with his brilliant catches. If Terry had tried that six weeks before, Leiber would have gone 0 for 4 and Davis would have fallen on his face chasing the first foul hit near him.

Within a week’s time, the Giants slipped into third place and from then on it was a three-way contest among New York, St. Louis and Chicago. By August 2, by which time Hubbell had won five straight, the Terrymen had won 15 of their last 19, a pace that had them within five lengths of the leaders. During the second week of August the Polo Grounders began a terrific gait that kept the pressure on Cards and Cubs alike and didn’t end until August 29, when the Gothamites lost to the Pirates after winning 15 in a row. At that point they had captured 35 out of their last 40 games.

New York Timesman John Kieran rhapsodized thusly in his “Sports of The Times” column:

Out of the fog that blurred their game,

Up from the dark that wrapped them `round,

Through bitter weeks to happy days –

Behold the Giants, pennant-bound!

In the fell clutch of batting slumps,

Bludgeoned by Pirates, Cards and Cubs,

The Giants looked the part of chumps

And played the role of diving dubs.

Clear from the fifth-place vale of tears,

Gaining by inning and by inch,

Turning the rasping jeers to cheers,

They came back slugging in the pinch.

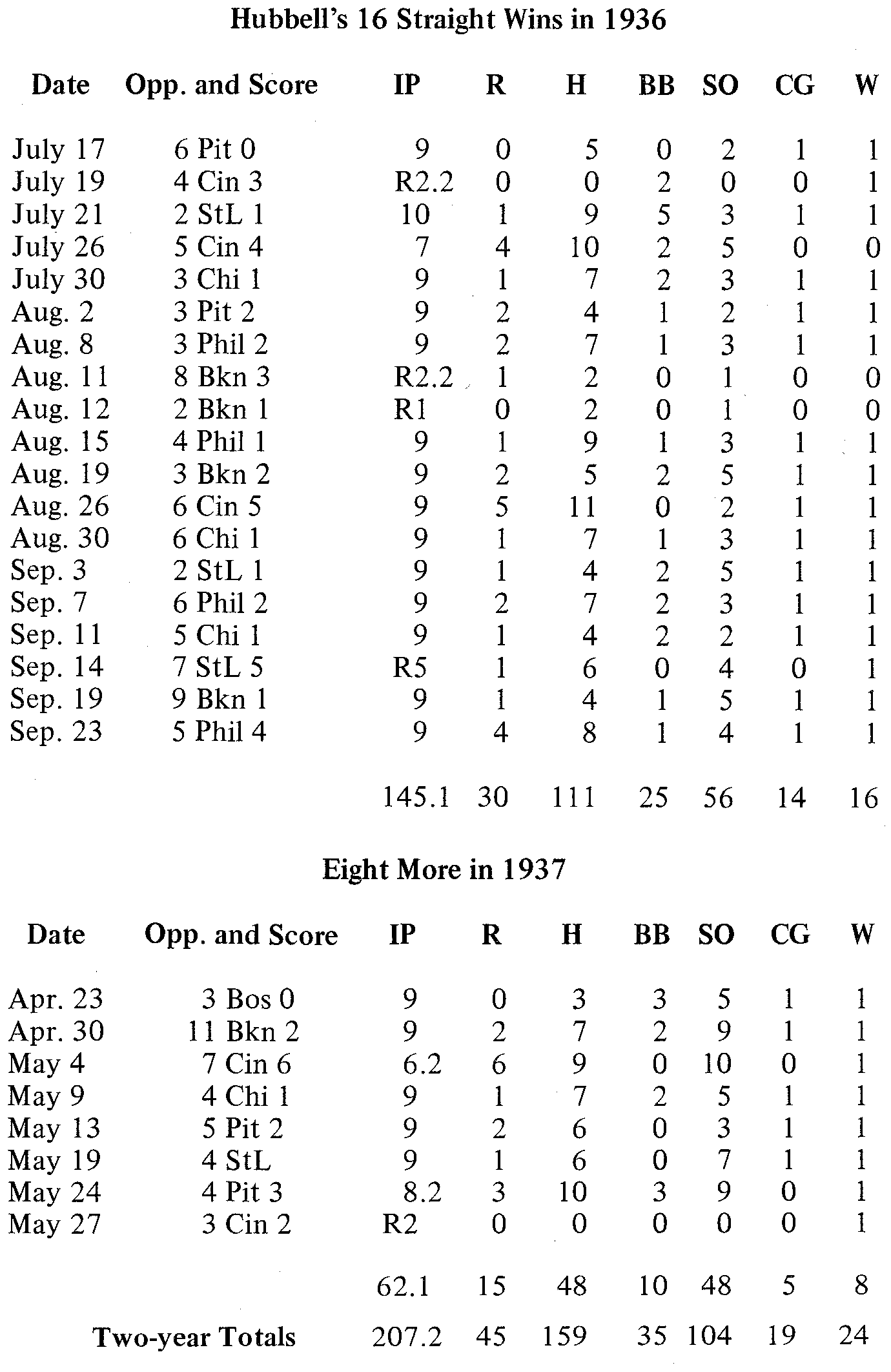

It was the month of August that put the Giants over. In third place at the start of that month, they swept into a lead of 3½ games by the 31st and went on to win the 1936 NL Pennant. Carl won 26 games, 16 of which were consecutive victories. He lost one of two decisions against the Yankees in the World Series, but the next season he picked right up again and won his first eight games.

Hubbell’s figures, of course, were outstanding. Over the course of his two-year win streak he hurled the equivalent of 23 nine-inning games. He allowed, roughly 7 hits and 2 runs per game and fanned 4.5 and walked 1.5 men per nine innings. While he pitched only two shutouts he held the opposition to a single run in nine other games. That he usually finished what he started is indicated by his complete game record. Of the 22 games he started during this long stretch, he completed 19 and required relief only three times.

Terry didn’t hesitate to use his ace in a relief role as the occasion required. When Coffman found himself in a jam on July 19, 1936, Carl came on to pitch a couple of excellent relief innings and “saved” the game, as it would be called today. And he was used in the same capacity several other times.

His best rescue job came in his 24th win on May 27, 1937. Again called on to replace Coffman, with the score tied in the eighth frame, he retired three Cincinnati batsmen on infield grounders, and in the last session got three more on pop flies. No one reached first.

More than once Carl, not especially noted for his batting, helped his cause with timely hits. On July 30, 1936, he drove in the tying run, then checked the Cubs for the rest of the game. Again on August 8, his “blazing single” after two were out in the seventh led to the winning score.

Probably his most satisfying blow came in a late season 1936 game against St. Louis. The score was tied in the ninth inning, as you must have surmised, and there were men on second and third, with one man out and Hubbell due to hit. The book, of course, cried for a pinch hitter, but Terry had the bit in his teeth by this time, and he waved Carl to the plate.

Hubbell missed two mighty swings, then lifted a puny fly to Pepper Martin in short right-center, a pop that fell only a few yards back of the clay infield. Whitehead, rushing in from third after the catch, found himself blocked off the plate by burly Spud Davis and slithered past the scoring station without touching it. But Burgess twisted and squirmed and somehow managed to reach past Davis’ blocking legs and touch the plate an instant before the catcher grabbed the ball.

Any long skein of victories is bound to be marked by controversies, and this one was no exception. There was, for instance, the famous “balk” incident of May 19, 1937, when Carl was seeking win No. 22. The Giants and the Cards were again fighting it out, this time for second place, when they met in St. Louis.

Trailing by one run in the top of the sixth, Whitehead led off with a single and Hubbell sacrificed him to second. While pitching to Dick Bartell, Dizzy Dean half turned toward second base and then, without halting his motion, fired to the plate. Bartell lifted an easy fly to left for what should have been the second out, but Umpire Barr ruled out the play and called a balk on Dean for failing to pause a full second in his delivery.

Whitehead was motioned to third and, after the ensuing argument had subsided, Bartell, batting again, sent a line drive to right-center which Martin dropped. There followed a couple of base hits and the resultant three runs sewed up the game.

Dizzy was so upset at the turn of events he took to throwing “knockdown” pitches at any one who dared show up at the plate with a bat in his hands. The Giants soon tired of this foolish game and presently Jimmy Ripple challenged Jerome, the challenge was accepted, and both teams tangled in one of those free-for-ails that enliven every season.

National League President Ford Frick slapped $50 fines on both Dean and Ripple and threw in a sharp reprimand for the pitcher, pointing out that every one had been warned in advance that the balk rule would be strictly enforced and, further, that Dean had already committed two balks in the game in question, each time being warned by the umpire.

Unabashed, Dizzy, loose-tongued as Memnon, counter-attacked by offering $1,000 to anybody who would print what he thought of his league president. Further, he shouted, he would not — positively not – appear in the All-Star game that year. If Dean had lived up to that threat he would have done himself a tremendous favor. It was in that All-Star game that Earl Averill stroked a line drive that broke Dizzy’s toe. As every one knows, Dean, rushing back into action before the toe mended, altered his pitching style to favor the injury and irreparably damaged his arm.

Brooklyn, the team that always gave Carl the most trouble, finally brought him down. On May 31st, before the second largest crowd in Polo Grounds history up to that time, the Dodgers combed him for 7 hits in the opening game of a doubleheader. They also drew 3 walks in the 3.1 innings he was on the mound. When he trudged down the center of the field in the middle of the fourth frame he was trailing 5-2. The final count was 10-3.

Between games of that twinbill there was a little ceremony. Hubbell was awarded the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award for the 1936 season. The fat man who handed that award to him was none other than Babe Ruth.