Celebrating the Nons: Many ‘Unofficial’ No-Hitters More Fascinating than the ‘Real’ Ones

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

As we are told by the good-hair talking heads on 24-hour sports networks—as well as by any newspaper, electronic fish wrap, podcast, or blog—the 2021 season featured nine no-hitters. But in 11 games a team was held hitless. Why the discrepancy? Two of those games were seven-inning games, and a 1991 committee had declared that for a no hitter to be “official,” it had to contain at least nine hitless innings. An inexplicably strict adherence to this concept is why the lesser number, nine, is usually cited by media members and fans.

This article will cover the various ways these now “non-official” no-hitters have been treated in the past while looking at a number of interesting no-hit games that have been relegated to lesser status.

1991 COMMITTEE ON STATISTICAL ACCURACY

In August 1991, Commissioner Fay Vincent announced the formation of a “committee on statistical accuracy”1 to settle the issue of whether Roger Maris and Babe Ruth should share the single-season record for home runs. Ruth had commonly been listed as the record holder for a 154-game season and Maris for 162 games. Vincent was influenced by a lengthy Roger Angell article in the May 27, 1991, issue of The New Yorker which included this passage:

There is no wish here to revive the shoutings and buzzings that accompanied the Maris achievement thirty years back, but I think the present commissioner and some brave commit tee should meet one of these days and quietly wield an eraser, instead of waiting for some young slugger to come along and do it for them with his bat.2

Vincent said he told his deputy, Steve Greenberg, “I think Roger [Angell] is right.” Vincent added in a 2022 telephone interview, “We couldn’t have two sets of records. It was an embarrassment. It smacked of Ford Frick determining that Roger Maris was a poor successor to Ruth.”3

The committee proclamation the following month of Maris being the sole record holder was well-received. It was offset by an uproar over a concomitant announcement: an “official” definition of a no-hitter as being games of nine innings or more that ended with no hits.4 The decree lopped from the list those games in which a team was held hitless but came up short of nine innings for the no-hit pitcher. Such games had been truncated for reasons such as darkness, rain, and mutual agreement.

Two no-hitters dropped from the “official list” were ones in which the hitless team did not have to bat in the last of the ninth because it had already won the game. Silver King had done this in 1890: holding Brooklyn hitless but losing the game while pitching for Chicago in the Players’ League. Few fans may have been aware of the King game, but most were familiar with a no-hitter pitched by the Yankees’ Andy Hawkins July 1, 1990, in Chicago. The game, but not the no hitter, had blown up in the last of the eighth when the White Sox scored four runs on two walks and three errors. The game made a bigger splash than most no hitters, leading both news and sports broadcasts that evening and being the top headlines in newspapers the next morning.5

Vincent wasn’t shy about what he saw as excessive excitement over Hawkins’s no-hitter: “I thought it was silly—a reaction by a lot of people who didn’t know much about baseball. Within historical context, it was beyond the baseball knowledge of a lot of people, not enough understanding of the history of how many get broken up. The ninth inning is a grave yard for no-hitters.”6

In recalling the committee activities more than 30 years later, Vincent emphasized he didn’t remember much and speculated that “people on the committee may have brought up the no-hitters.” Eminent base ball historian David Voigt was a member of the committee.7 A family friend of Voigt’s recalls him having a different recollection. Steve Ferenchick said he once asked Voigt if he thought it was fair to take away so many no-hitters. “I still remember him grimacing and saying something like, ‘No. We discussed it and a lot of us had the same view I did, that those no-hitters shouldn’t be removed from the books. But Fay Vincent came in with his opinion, and the rest of us were basically brought in to rubberstamp it. I wouldn’t have changed the rule there but it was his call, not mine.’”8

While the Hawkins no-hitter received oversized attention that still resonates, three subsequent no hitters of this type (full games but with the hitless team not batting in the ninth) have been treated as footnotes: Matt Young of Boston April 12, 1992; Jered Weaver and Jose Arredondo of Anaheim June 28, 2008; and Hunter Greene and Art Warren of Cincinnati May 15, 2022.

PREVIOUS TREATMENT OF NO-HITTERS

Contrary to some reports, no “official” definition of a no-hitter existed before 1991, not that one was needed. The Sporting News, in its record books (One for the Book and later The Official Baseball Record Book) listed all regulation games in which a team was held hitless. The lists included the many times a team was held hit less for fewer than nine innings, and readers in those days were deemed discerning enough to ascribe their opinions to them. Today, people seem to be overly deferential to the 1991 committee definition.

In addition, the TSN record books listed all games in which a team was held hitless for at least the first nine innings but got a hit or hits in extra innings. Of course, these really aren’t no-hitters; on the other hand, how many games are more notable than Harvey Haddix pitching 12 innings before having his perfect game and then no-hitter broken up in the 13th?9

Not as impressive but still noteworthy is Harry McIntire of Brooklyn having a no-hitter for 102/3 innings before giving up a single to Claude Ritchey of Pittsburgh on August 1, 1906. McIntire gave up three more hits and lost the game in 13 innings. A number of pitchers have had a no-hitter through 10 innings, with most of them winning the game at that point. Sam Kimber of Brooklyn did it against Toledo October 4, 1884. George “Hooks” Wiltse of the New York Giants had a perfect game versus Philadelphia July 4, 1908, before hitting a batter; he still completed a 10-inning no-hitter. Cincinnati’s Fred Toney’s 10-inning no-hitter against Chicago on May 2, 1917, stands out because the opposing pitcher, Jim “Hippo” Vaughn, had held the Reds hitless for the first nine innings. In addition, two pitchers—Francisco Cordova and Ricardo Rincon of Pittsburgh—combined for a 10-inning no-hitter on July 12, 1997, against Houston.

Jim Maloney won a 10-inning no-hitter for Cincin nati at Chicago August 19, 1965; earlier in the season he had also pitched 10 hitless innings before giving up a home run in the 11th inning to Johnny Lewis of New York on June 14 (a game in which Maloney struck out 18 batters). Maloney remains the only pitcher to twice pitch hitless ball over the first 10 innings of a game. Maloney got more support from the Reds in his next no-hitter, a 10-0 win over Houston April 30, 1969. How many no-hitters did Maloney have to this point in his career? In their game stories, the Cincinnati Enquirer, Dayton Daily News, and St. Louis Post Dispatch referred to Maloney’s no-hitter being his third. Jim Ferguson, for the Dayton paper, wrote, “Maloney was on his way to the record books as one of only five men in the history of baseball to hurl as many as three no-hitters. Sandy Koufax is alone with four such games while Maloney joins Cy Young, Bob Feller and Larry Corcoran, a name from the 1880s, with three.” On the other hand, United Press International reporter Vito Sellino labeled the gem as Maloney’s second.10

So no-hitters were counted by however one wanted to count them.

NOTABLE NONS

Of the true no-hitters of fewer than nine innings, some are distinctive. They fall into several categories determined by several factors, sometimes unique circumstance and sometimes by the attempts of various teams or leagues to cope.

Played to Natural Conclusions

As for games that truly were no-hitters, but fewer than nine innings, some were not shortened but were played to their natural conclusion. The no-hitters by King, Hawkins, Weaver/Arredondo, and Greene/Warren were nine innings although the hitless team batted in only eight of those.

During the period when doubleheaders were scheduled for seven innings under “COVID rules” in 2020 and 2021, two no-hitters took place: Madison Bumgarner of Arizona no-hit Atlanta on April 25, 2021, and Collin McHugh, Josh Fleming, Diego Castillo, Matt Wisler, and Pete Fairbanks of Tampa Bay held Cleveland hitless on July 7, 2021. Both of these occurred in the second games of seven-inning doubleheaders.11

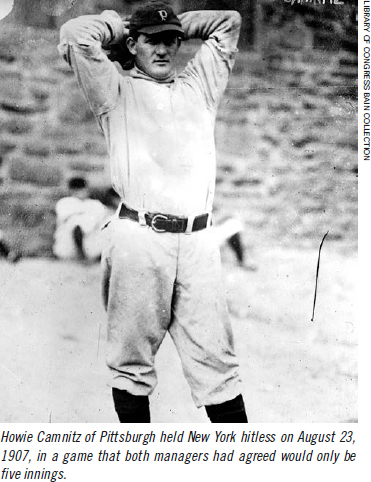

In addition, some no-hitters happened in games that, by mutual agreement of the teams, were scheduled for fewer than nine innings. Fred Shaw of Providence did it at Buffalo in the first game of a doubleheader on October 7, 1885; “By mutual consent the clubs played only the innings needed to make a record, and the players, umpire, reporters, and the dozen spectators were glad when the two hours in the cold were ended,” wrote the Buffalo Express. Jake Weimer of Cincinnati no-hit Brooklyn on August 24, 1906, and won in the last of the seventh when the Reds scored; the second game of a doubleheader, it was scheduled for seven innings by pre-agreement. Howie Camnitz of Pittsburgh held New York hitless on August 23, 1907, in the second game of a doubleheader, scheduled for five innings by agreement of both managers.12

Ed Karger of the St. Louis Cardinals pitched a perfect game of seven innings August 11, 1907; the second game of a doubleheader, it was set for seven innings by a prior mutual agreement of St. Louis and Boston.13

Resurrection

On June 12, 1959, Mike McCormick of San Francisco carried a no-hitter into the last of the sixth at Philadelphia. After walking two batters, McCormick gave up a single to Richie Ashburn to load the bases. With Gene Freese next up, time was called because of rain, and eventually the game was called. Because it was an uncompleted inning, the game reverted to the last full inning, San Francisco winning 3-0 and McCormick getting his no-hitter back. (A 1962 rule change called for the reversion to occur only if what happened in the top of an uncompleted inning affected the outcome of the game; in 1980, the rules changed to eliminate any reversions by making these suspended games.)14

A no-hitter by Jimmy Dygert and Rube Waddell of the Philadelphia Athletics on August 29, 1906, may have been resurrected in similar fashion to McCormick’s although it is unclear if a play in the third inning of the game was called a hit or an error. Dygert pitched the first three innings with Chicago’s Ed Hahn reaching base in the third when third baseman John Knight fumbled his bunt. Newspaper accounts and box scores differed on if it had been called a hit or error. Waddell relieved Dygert in the fourth—and gave up a run with out a hit15—and then pitched a hitless fifth. Chicago rallied in the top of the sixth and scored two runs to take a 5-4 lead with a walk, error, and singles by Jiggs Donahue and Billy Sullivan. However, with the Athletics batting in the last of the sixth, the game was called by rain and reverted to the bottom of the fifth, wiping out two White Sox runs and hits.

Uncertainty over the status of the scoring decision on Hahn’s third-inning bunt lingered. The game was listed among the no-hitters in The Sporting News Official Baseball Record Book of 1974, but by the 1977 edition of the book, it had been removed.

Another disputed no-hitter, also involving Waddell, was on August 15, 1905, when the Athletics beat St. Louis, 2-0, in a game called by rain after five innings. Morning newspapers in St. Louis and Philadelphia noted one hit for St. Louis, the result of Waddell slip ping while fielding a grounder, but by the afternoon editions, the hit had been removed from the box scores.

First Win for a Forgotten Team

Minnesota’s first major-league team—an 1884 St. Paul squad that was one of the last survivors of the minor-league Northwestern League, finishing its season in the now-recognized-as-major Union Association—is an unremarkable story. The nine games it played were all on the road, and St. Paul lost its first four. It played in St. Louis October 5. Charlie Sweeney struck out six St. Paul batters in the first two innings before switching spots with left fielder Henry Boyle. The fielders did well on the slippery grounds except for the fourth inning, when St. Louis made two errors to allow St. Paul to score a run. Heavy rain came down after the fifth inning, causing a delay. The rain stopped but umpire Harry McCaffery deemed the field too wet to play and called the game. St. Paul had a 1-0 win in a game in which it did not tally a hit.16

Debuts

Cincinnati’s Bumpus Jones, in his first major-league game, no-hit Pittsburg October 15, 1892, and is often credited as the only pitcher to hurl a no-hitter in his debut.17 However, he was pre-dated in this feat by George Nicol of St. Louis in the American Association. On September 23, 1890, Nicol beat a reorganized and hapless Athletic team of Philadelphia following an en masse resignation of Athletic players a week before when the team couldn’t meet its payroll. With the score 21-2 for St. Louis and darkness setting in, the game was stopped after seven innings.

Leon “Red” Ames of the New York Giants pitched his first game in the majors on September 14, 1903, and held St. Louis hitless in the second game of a double header, which was called after five innings either by darkness or threatening weather, depending on which St. Louis newspaper you choose to rely on.18

Last by Darkness

The last game called—not suspended—by darkness was at Wrigley Field September 8, 1985.19 The last no hitter stopped by darkness, rather than weather, was the second game of a doubleheader at Braves Field June 22, 1944. Boston’s Jim Tobin held Philadelphia hitless over five innings before it was too late to continue under existing light.

OTHER “NON” TIDBITS

In a Montreal at San Diego game June 3, 1995, Pedro Martinez became the only pitcher to have a chance to complete an extra-inning perfect game. Unlike Harvey Haddix—who perpetually knew he would have to keep laboring for at least two more innings for a perfect game—Martinez took the mound with a lead in the last of the 10th. However, he gave up a leadoff double to Bip Roberts before being relieved by Mel Rojas, who retired the final three batters.

Tom Hughes of New York was credited as a no-hit pitcher who gave up the most runs when he lost, 5-0 to Cleveland in the second game of a doubleheader August 30, 1910.20 However, this was recognized among lists of no-hitters only because he had pitched nine hitless innings before giving up a hit in the 10th and six more in the 11th. Among true no-hit pitchers, Andy Hawkins gave up the most runs in his 4-0 loss to the White Sox July 1, 1990.

CONCLUSION

As luminaries ranging from Leonard Koppett to Dave Smith have stated, “official” means nothing more than “of the office.” It does not necessarily mean correct. It doesn’t mean that fans, researchers, and historians have to accept Ty Cobb‘s “official” career-hit total as 4,191 or that he had a higher batting average than Napoleon Lajoie in 1910 or that the historical records of the 1901-60 Washington American League team belong to the 1961-71 Washington Senators.21 And it certainly does not require the delusion that a regulation game in which a team is held hitless is not a no-hitter.22

Vincent acknowledged the controversy over the decision on no-hitters but wasn’t fazed by it. He said that he and Bart Giamatti, his predecessor as commissioner, had a philosophy: “Those are the issues that make baseball great, issues that aren’t life and death but that generate disagreement and discussion.”

STEW THORNLEY has been a SABR member since 1979 and helped to found the Halsey Hall Chapter (Where the Action Is!) in 1985. He has received the SABR-Macmillan Baseball Research Award in 1988, the USA Today Baseball Weekly Award (for the best convention research presentation) in 1998, and the Bob Davids Award in 2016.

Author’s Note

Repetitious as they are, the quotation marks around “official” are used intentionally. If readers interpret this overuse as a sign of the author’s disdain for an “official” definition, they are invited to make such an inference.

The author appreciates the help of many SABR members, including John Thorn, Scott Merzbach, Steve Ferenchick, Bob Komoroski, Dave Lande, and Steve Gietschier.

Fay Vincent and/or his committee attempted to de-officialize many no-hitters; fortunately several sources still list them. One of the best is Dirk Lammers’s site, nonohitters.com. In addition to all the “official” no-hitters listed for the White and integrated leagues (with more coming from Negro Leagues from 1920 to 1948), the site has the so-called “non” no-hitters as well as no-hitters from around the world and no-hitters from the All-American Girls Professional Base Ball League.

Notes

1. Jim Donaghy, Associated Press, “Extra Inning,” September 5, 1991, https://apnews.com/article/9a48ac96f06749fa10d0a8d97f2fc8df.

2. Roger Angell, “The Sporting Scene: Homeric Tales” The New Yorker, May 27, 1991: 69.

3. Author telephone interview with Fay Vincent, July 18, 2022.

4. Steve Gietschier, “Year in Review: Two Record-Keeping Revisions,” The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide, 1991: 169, and Donaghy, “Extra Inning,” Associated Press, September 5, 1991, https://apnews.com/article/9a48ac96f06749fa10d0a8d97f2fc8df. Gietschier’s piece covered the home-run record and the no-hitter definition. Donaghy did not even mention the issue of the record for home runs, even though this had been the focus of news when the committee was announced. Regardless of the committee’s decision, in the ensuing years The Sporting News Complete Baseball Record Book continued to list the single-season records for home runs for both a 154-game and 162-game season as well as listing all types of no-hitters, including the “non-official” ones.

5. The no-hitter was at the top of the front page—the front page of the entire newspaper, not the sports page—in USA Today on July 2, 1990.

6. Interview with Vincent, July 18, 2022. Vincent is correct that many no-hitters get broken up in the ninth. Since 1961, approximately 48 percent of no-hit games carried into the ninth inning have been broken up in the ninth. https://milkeespress.com/lostninth.html.

7. In addition to Vincent and Voigt, then a professor of sociology at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania, the other committee members were Rich Levin, director of public relations for the commissioner’s office; Michael Bernstein, manager of publishing of Major League Baseball Properties; Seymour Siwoff, general manager of the Elias Sports Bureau; Jack Lang, executive secretary of the Baseball Writer’s Association of America; Joe Durso, reporter for The New York Times, and George Kirsch, professor of history at Manhattan College in New York.

8. Submission from Steve Ferenchick on SABR-L, the SABR listserv, June 25, 2022.

9. A typically inane exchange between Archie and Meathead on All in the Family (Season 3, Episode 17—Archie Goes Too Far, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3mesNGrPcE) centers on whether Haddix did or did not pitch a perfect game. With 25 cents at stake, the pair never resolved the bet.

10. Bob Hertzel, “Maloney Throws No-Hitter!,’” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 1969: 61; Jim Ferguson, “Chaney‘s Fielding Gem Helps Maloney,” Dayton Daily News, May 1, 1969: 22; “Maloney Takes Casual Approach to No-Hitter,” St Louis Post-Dispatch (reference to third no-hitter in caption for UPI Telephoto), May 1, 1969: 1E. Vito Stellino, “Cincinnati’s Jim Maloney No-Hits Astros,” (UPI), Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), May 1, 1969: 12.

11. Although the Official Baseball Rules define a “double-header” as “two regularly scheduled or rescheduled games, played in immediate succession,” the term doubleheader is common parlance for two games in the same day and is used here, even though Bumgarner’s no-hitter was in the second game of a day-night twinbill.

12. “Good-By Baseball,” Buffalo Express, October 8, 1885: 2; “All Out Easy,” Cincinnati Post, August 25, 1906: 6; “Two Wins Put Pirates Back in Second Place,” Pittsburgh Post, August 24, 1907: 6. Another no-hitter, by Jack Stivetts of Boston versus Washington on October 15, 1892, was called by mutual agreement after five innings to allow Boston to catch a train; however, this was not a pre-game agreement for a set number of innings. King Cole of the Chicago Cubs pitched a truncated no-hitter at St. Louis July 31, 1910, in a game called by a predetermined end time (not a predetermined innings limit) to allow both teams to catch a train to New York.

13. Three other pitchers have perfect games of fewer than nine innings: Rube Vickers of the Philadelphia Athletics versus Washington October 5, 1907 (second game of doubleheader), called by darkness after five innings; Dean Chance of Minnesota versus Boston August 6, 1967, called by rain in the last of the fifth; and David Palmer of Montreal versus St. Louis April 21, 1984 (second game of doubleheader), called by rain after five innings.

14. San Francisco had a run scored in the top of the sixth erased, making the final a 3-0 win for the Giants. Prior to this, the erasing of an uncompleted inning that did not affect the game outcome was inconsistent and uncertain. These included several no-hitters although none of them erased a hit that resurrected a no-hitter such as was the case for McCormick. George Van Haltren of Chicago no-hit Pittsburg in a six- or seven-inning game on June 21, 1888; the Chicago and Pittsburg newspapers differed on whether or not the uncompleted seventh inning remained part of the game. King Cole’s July 31, 1910, game is also fuzzy as to whether an uncompleted inning was kept on the books. Two pitchers had no-hitters in games in which completed innings apparently were counted: Ed Stein of Brooklyn June 2, 1894, and Elton “Ice Box” Chamberlain of Cincinnati September 23, 1893.

15. Beyond the disagreement on a hit or error on Hahn’s batted ball in the third, line scores differ regarding the innings in which runs were scored. The August 30, 1906, (page 13) Philadelphia Inquirer shows 012 00 for Chicago and 110 01 for Philadelphia. The August 30, 1906, (page 8) Scranton Times has 110 10 for Chicago and 112 00 for Philadelphia. Retrosheet (https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1906/B08290PHA1906.htm) has a line score similar to that of the Philadelphia paper and also indicates a hit for Hahn.

16. “The St. Paul Unions: Minnesota’s First Major League Team” by Stew Thornley, https://stewthornley.net/unions.html.

17. Note on the use of “Pittsburg”: In a post on SABR-L June 25, 2022, John Husman cited a page from the Popular Pittsburgh website and wrote, “In 1890, the United States Board of Geographic Names, which was created to bring consistency to the spellings of locations throughout the country, deemed that all cities ending in ‘burgh’ must drop the ‘h’ in the spirit of uniformity…Eventually, a special meeting of the U.S. Board of Geographic Names was arranged. On July 19, 1911, the board met. A preponderance of evidence citing Pittsburgh spelled with the ‘h’ over the decades convinced the board to reinstate the final letter.”

18. On Opening Day in 1909 (April 15), Ames had a no-hitter for 91/3 innings for the Giants against Brooklyn. He lost the no-hitter in the 10th inning and the game in the 13th.

19. The Cincinnati-Chicago game—in which Pete Rose got his 4,191st hit— was stopped by darkness after nine innings with the score tied, 5-5. It was determined that the game would be replayed in its entirety if it was necessary (it was not) to bring the teams back together to determine a division title. However, in 1969 the National League had changed its rules so that regulation games stopped by darkness would be suspended, not called. This happened after a controversial Cubs loss to Montreal June 22, 1969, when the game was called by darkness.

20. ESPN made this oranges-to-apples comparison in its coverage of Andy Hawkins’s July 1, 1990, no-hitter, comparing the four runs Hawkins gave up without a hit to the runs Hughes gave up with multiple hits in extra innings, a comparison that is not valid.

21. Tom Mee, who was part of the Minnesota Twins public-relations department from 1961 to 1991, claimed that American League president Joe Cronin in the 1960s declared that the expansion Senators owned the records and history of the Washington Nationals of Walter Johnson, Cecil Travis, and Ossie Bluege. Historians never bought into this manipulation, and in 2020 the Twins even publicly displayed their heritage with banners at their ballpark for the 1924, 1925, and 1933 American League pennants won by the Nationals (1924 also being a world championship).

22. Many of the fewer-than-nine-inning no-hitters featured in the SABR Baseball Games Project include a disclaimer with language along the lines of the no-hitter being counted as until 1991, when a committee edict removed them from the ranks. These, of course, are still no-hitters, just not ones “officially” recognized by Major League Baseball.