Chicago, Latina Culture, and Community of Women’s Baseball

This article was written by Emalee Nelson

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

While baseball’s origin story began on the East Coast, the Midwest has been a vital part of the growth of America’s pastime. Although a disastrous fire in 1871 temporarily stunted the city’s growth, Chicago at the end of the nineteenth century was a growing hub for commerce and culture. As the United States expanded westward, Chicago turned from being a “city out west” to a midway point between the populated Eastern seaboard and the Western frontier. As a result, baseball quickly followed to the Windy City.

Following the Mexican Revolution in the early twentieth century, an influx of immigrants would find refuge in the Midwest, including Chicago and the surrounding area. Eager to build their new lives, Mexican Americans found solace in their Catholic faith and baseball. While many community teams sprang up for young men, a handful of women’s teams were created during the 1930s and 1940s.

In the years before World War II, local parishes created women’s teams as opportunities for young women to gather in a safe environment and play baseball. Following the war, the Great Lakes region—notably Chicago and surrounding areas—would also attract Latina baseball players through the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. This article will briefly discuss the intersections of women’s sport and Latina culture in Chicago-area baseball. In doing so, this article also hopes to continue filling an understudied gap in the historical tapestry of women’s baseball.

¡HOLA, CHICAGO!

To understand the importance of women playing baseball in Chicago and surrounding areas, it is crucial to begin with the city’s baseball origins. The first club for men was organized in 1856. As with the early teams which formed in New York City, camaraderie and socializing were key aspects of these clubs. Following the Civil War, many Chicagoans looked to the sport as a premier avenue for physical recreation and fellowship. Tournaments held in the city attracted teams from nearby areas such as Detroit, Bloomington, Rockford, Milwaukee, and Freeport.

Unfortunately, these games didn’t include all of the area’s best players, because these teams, such as the Excelsior Club and the Chicago Base Ball Club, largely consisted of only White men. Even in a northern region which collectively mourned the assassination of their homegrown president—the man who delivered the Emancipation Proclamation—racially exclusionary practices were the norm in Chicago. This was evident in 1870 when a Black ball club known as the Blue Stockings was excluded from an amateur city tournament. Although the Blue Stockings would go on to become quite successful in the “colored” circuit of competition—even traveling to a handful of East Coast cities—a prominent theme was evident in Chicago baseball. In short, race mattered.

However, race was not a binary issue of Black or White during a time of increased Latino immigration. The Mexican Revolution was a violent conflict that was drawn out for nearly a decade between 1910 and 1920. Many Mexicans fled the fighting for the prospect of a more peaceful life. The Midwest was an enticing destination for them, and Mexican presence served as a sort of buffer in the middle of the racial divide. Segregation was becoming fully entrenched in the early twentieth century, even in northern cities, with baseball itself became increasingly segregated from the late nineteenth into the early twentieth century. Although professional teams affiliated with the American and National Leagues held to the “gentlemen’s agreement” which excluded Black players from joining, certain Latino players were able to cross this color line.

Segregation throughout league-affiliated baseball in the United States did not discourage non-White athletes from picking up bats and gloves. Many of Chicago’s first baseball fields were built around rail lines. Given that the railroad industry was a popular source of employment for many Mexican immigrants, America’s pastime soon spread to these communities of new citizens. Given the popularity of the sport and the relative ease with which one could find a field and makeshift equipment, baseball helped these young immigrants prove their American-ness, while imitating a familiar memory of playing on teams in the barrios of their homeland.

FATHER, SON, AND HOLY SWING

Though it was a recreational pastime, baseball was crucial in fostering a strong sense of ethnic identity and pride within migrant communities. So was churchgoing, and places of worship were another space where Mexican immigrant families could congregate to create a sense of community and belonging in their new country. Catholic churches played a pivotal role in the formation of Mexican community sports teams, especially for youth. Young players were encouraged to participate for their physical health, but also their parents sought the positive impact teamwork and camaraderie could have on their children.

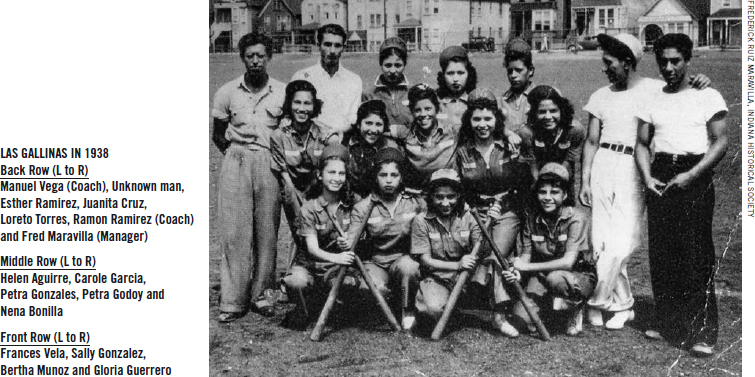

These teams were not just available for young boys in Chicago; teams for girls and women were formed, as well. One such was Las Gallinas, which emerged as a team affiliated with Our Lady of Guadalupe, a Catholic church in East Chicago, Indiana. Such women’s teams were usually managed by all-male staff.

The women’s teams would often play on a field nearby where the men’s teams were playing at the same time. Sometimes, the women would play in the morning and the men in the afternoon. The men’s and women’s teams would often travel together. This was evident with Las Gallinas (The Hens), the lady counterpart to Los Gallos (The Roosters). The church provided the equipment, the uniforms, and even a (male) coach for Las Gallinas. Frederick Maravila was the team manager of Las Gallinas during the 1937 season, but also played on the men’s baseball team.

Almost all the girls had some sort of affiliation with the church, according to Gloria Guerrero Fraire, a former player for Las Gallinas. Amidst the competitive spirit, religious tones of modesty were evident. Fraire recalls, “You could tell from the uniforms that the sisters wanted them to dress modestly. No shorts, and limbs were covered.” This sentiment furthered the notion of religious influence and importance within the larger Mexican immigrant culture.

Fraire continues, “We used to play and then the Gallos used to play. It was a big festival day. Everybody would go out there and watch us play baseballs So with two games, it was a long day. Lots of people would take their sandwiches and tacos.” Her teammate, Carol Garcia Martinez, also remembers, “Some young women were active in all types of sports in school. We formed community teams because we enjoyed sports. Most of our parents were supportive as long as our older brothers and male friends were watching over us. We played nine innings and basically played by the same rules as the men. Our games were extremely competitive.” These women were pioneers in their time during the 1930s and 1940s, often becoming some of the first girls to compete in varsity sports at their local high school, years before Title IX. The women were talented, deserving athletes, sometimes drawing crowds of a few hundred to their games.

Both men’s and women’s teams often had the responsibility to promote themselves and to find teams to barnstorm against. They would feature themselves in local newspapers to try to find a worthy competitor. Las Gallinas would play against teams in South Chicago, Whiting, Gary, and Hessville, indicating they would travel, but mostly within the state. Word of mouth remained the best method to find an opponent.

Surprisingly, most of the women playing were in their teenage years, not yet adults. This made them first generation Mexican Americans, rather than immigrants from Mexico like their parents. These parents made sure the girls were on time for all games and practice, implying that they were supportive of these young women playing baseball. This was quite opposite of the usual stigma associated with women participating in sport, especially a physically demanding sport like baseball. Furthermore, parents were supportive of their children joining sport teams because it gave them useful skills to be utilized in the political arena and fight for social justice.

A CUBAN CATCH

Although many of these smaller, church-affiliated teams folded during the wartime years, Latina presence would return to Chicago ballfields following World War II. During the war years, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) was the creation of Chicago-based business magnates Philip Wrigley and Arthur Meyerhoff. The first teams called cities in the Great Lakes region their homes. After a handful of successful years, the AAGPBL expanded their efforts by creating a barnstorming tour outside of the Midwest to expand their fanbase, while also attracting the more talent. Before the 1947 season, the league held spring training in Havana, Cuba.

The AAGPBL teams played a series of exhibition games against each other while in Cuba, but also played a team of the best Cuban women baseball players. This proved to be top notch entertainment on the Caribbean island, since the women’s games out-drew the crowds of the men’s teams also training in Cuba, notably the Brooklyn Dodgers and their up-and-coming phenom Jackie Robinson. Wrigley and Meyerhoff used these exhibitions to scout additional talent to join the league. As a result, a handful of Cuban women signed contracts and packed their bags for the United States.

While this was an unprecedented opportunity to play professional baseball, these women understood the significance of departing a country on the verge of turmoil. Similar to those only a few decades prior escaping the turbulent Mexican Revolution, the Midwest provided a haven of opportunity. Isabel Alvarez, who played for the Fort Wayne Daisies and other teams, recalls, “I left home tired and tense from all the endless preparations and from all the warnings about my safety in Communist country.” Yet, Alvarez and her Cuban league-mates found a community of solidarity in sport.

Migdalia “Mickey” Perez bounced around between Chicago, Springfield, and Battle Creek before landing with the Rockford Peaches from 1952 through 1954. She was known for being a savvy, skillful utility player and pitcher, who “used a hole in a back fence as her pitching target and was never satisfied until she could hurl ten balls in a row without missing.” While growing up in Cuba, she studied English and became the “official translator and foster mother of the other Cuban girls.” During her time in Rockford, she met James Jinright, the groundskeeper for the Peaches. The pair tied the knot in July 1952, eventually residing in Florida until she passed away in October 2019.

However, when Mickey was not present, the language barrier did materialize. Ysora Castillo Kinney left Cuba when she was still a teenager to play for the Chicago Colleens in 1947. During the 1950 season, she played for the Kalamazoo Lassies, and was kicked out of a game for talking back to an umpire in Spanish. She hardly remembers the incident. Instead, she recalls in an interview with Buffington Post Miami, “I said something I wasn’t supposed to say. I don’t remember. I was real happy all the time, and I was yelling all the time.” The Daily Oklahoman referred to Castillo-Kinney as “the pretty Cuban third- baseman…[who] does not speak English, but she is a Spanish pepperpot once the game gets underway.” With this spirited persona, she would serenade audiences in her native language, notably a Spanish rendition of “Yours (Quiéreme Mucho)” prior to a July 1949 scrimmage between the Springfield Sallies and Chicago Colleens in Austin, Texas.

In 1950, Isabel Alvarez was traded after the season from the Colleens to the Fort Wayne Daisies. Professionally for Alvarez, this was an upgrade, as the Daisies were a full-fledged league team, as opposed to the rookie-level touring Colleens. Unfortunately for Alvarez, none of her Cuban teammates were traded with her. She recalls her transition: “I was alone in Fort Wayne. Sometimes when you can’t communicate, you feel maybe [others] don’t want you around. Everyone has a clique, they run around in groups.” In addition to feeling socially isolated, Alvarez believed the language barrier also inhibited her ability as a baseball player given her immense difficulty communicating with her new teammates.

These feelings of loneliness and isolation were not unique to this small group of Cuban women. “Indeed, the cultural chasm between U.S. and Latin societies, which included historical, religious, ethnic, and language differences was formidable and sometimes impassible.” Even the most successful of players, male or female, were subject to discouragement, even questioning their purpose for playing baseball in the United States. For Alvarez, the homesickness was evident, and she returned to Cuba following the season. By then she had been in the league for two years but was just seventeen years old. At home, she told her mother of her difficulties communicating with her new teammates. She was sad and discouraged. Her mother, who had urged Alvarez to join the league two years prior, reminded her “[she] had to do her job and forget about Cuba.” To her mother’s happiness, she did return to Fort Wayne for the 1951 campaign.

Awaiting Alvarez in Fort Wayne for the 1951 season was sixteen-year-old Catherine “Katie” Horstman, the newest member of the Daisies. In an interview many years later, Katie laughingly recalled a particular encounter with her new teammate. “When I first started with Fort Wayne in 1951, I pitched a lot of batting practice. The very first girl I met spoke Spanish. It was Isabel Alvarez, who was Cuban. I thought, ‘They’ve got Cubans on their team. I live sixty-five miles from Fort Wayne, and I never even heard of women’s pro baseball!’”

CONCLUSION

While Chicago’s baseball historical tapestry is typically represented by the ivy-covered walls of Wrigley and the 1919 Black Sox scandal, it is important to acknowledge that the city and surrounding area is home to many lively sporting histories on smaller sandlots. Immigration and the Manifest Destiny narrative are essential pieces of America’s nineteenth century—and so is baseball. The promises of freedom and opportunity attracted migrants from all corners of the world eager to vie for a chance at the American dream. If any sport could embody this desire, baseball proved to be the perfect vehicle to celebrate new opportunity and build community pride.

EMALEE NELSON is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on the experience of women in sport during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, including topics of gender, sexuality, expressions of femininity, and race. She also works for Texas Athletics, enjoys cheering on the Texas Longhorns and listening to her hometown Kansas City Royals baseball games on the radio.

Notes

1. Peter Morris, Baseball Pioneers: 1850-1870, “Excelsiors of Chicago, Prewar” (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Inc., 2012).

2. Brian McKenna, “Sputtering Towards Respectability: Chicago’s Journey to the Big Leagues,” in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago, Society for American Baseball Research, 2015, https://sabr.org/journal/article/sputtering-towards-respectability-chicagos-journey-to-the-big-leagues. Accessed June 11, 2023.

3. McKenna, “Sputtering Towards Respectability: Chicago’s Journey to the Big Leagues;” see also Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1870.

4. Adrian Burgos, Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

5. McKenna, “Sputtering Towards Respectability: Chicago’s Journey to the Big Leagues.”

6. Richard Santillán, Gene T. Chavez, Rod Martínez, et. al., Mexican American Baseball in Kansas City (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2018), 25.

7. East Chicago is aptly named, located so near to Chicago, Illinois, today it takes less than half an hour to drive from the site of the old Comiskey Park to Our Lady of Guadalupe. See Google Maps https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Our+Lady+of+Guadalupe+Church,+Deodar+Street,+East+Chicago,+Indiana/Guaranteed+Rate+Field,+333+W+35th+St,+Chicago,+IL+60616.

8. John Fraire. “Mexicans Playing Baseball in Indiana Harbor, 1925-1942.” Indiana Magazine of History 110, no. 2 (2014): 120-45. https://doi.org/10.5378/indimagahist.110.2.0120.

12. John Fraire. “Mexicans Playing Baseball.”

13. John Fraire. “Mexicans Playing Baseball.”

14. John Fraire. “Mexicans Playing Baseball.”

16. John Fraire. “Mexicans Playing Baseball.”

17. Meaghann Campbell, #Shortstops: Spring Training in Cuba, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Accessed June 4, 2023, https://baseballhall.org/discover/shortstops/spring-training%20in%20Cuba.

18. Terry Doran, “In Cuba, people are important,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, April 28, 1996.

19. For a comprehensive summary of Isabel Alvarez’s life, see Kat Williams’s Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez: The Improbable Life of a Cuban American Baseball Star (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020).

20. All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, “Migdalia Perez” Press Release, 1950.

21. “Migdalia Perez” Press Release, 1950.

22. W.C. Madden, The Women of the AAGPBL: A Biographical Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1997), 192.

23. Christiana Lilly, “Ysora Kinney, 79-Year-Old Hospital Volunteer, Talks Pioneering Past in Women’s Baseball,” Huffington Post Miami, May 9, 2012, accessed March 18, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/04/04/ysora-kinney-womens-baseball_n_1403283.html. Accessed June 11, 2023.

24. Wally Wallis, “These Gals Expert at Running Bases,” Daily Oklahoman, 1949.

25. “Colleens and Sallies Steam Up For Final Thriller Here Tonight,” Austin American, July 8, 1949.

26. Marilyn Cohen, No Women in the Clubhouse (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009), 67.

27. Samuel Regalado, Viva Baseball: Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998) 93.

29. Jim Sargent, We Were the All-American Girls; Interviews with Players of the AAGPBL, 1943-1954 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013) 15.