Chief Bender: A Marksman at the Traps and on the Mound

This article was written by Robert D. Warrington

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

A circa 1912 portrait of Chief Bender probably taken for advertising purposes when he was a sporting goods salesman/consultant at Wanamaker’s Department Store in Philadelphia. The shotguns in the background have price tags dangling from strings attached to their trigger guards. The gold pendant hanging from a fob on Bender’s waist was given to players by the Athletics’ club for winning the 1911 World Series. (Author’s Collection)

In early twentieth century America, baseball and trapshooting went hand-in-hand for major league ballplayers. Many star players, and those not so prominent, were “scarcely able to wait until the diamond season is ended so they may rush to the gun rack, select their favorite firearms, and strive for records at the traps.”1 For some ballplayers, trapshooting was far more than a recreational activity intended to pass the time enjoyably until spring training. They participated in shooting tournaments that were as intensely competitive as they were financially rewarding. Matches between players became extensions of their rivalries on the diamond, and the trapshooting industry used baseball stars to lure people to take up the sport of shooting. Charles Albert “Chief” Bender excelled in baseball and trapshooting, and both sports played important roles in his life. While his career in baseball has been extensively analyzed, Bender’s success as a trapshooter among major league ballplayers of his era is less well known. His involvement in this sport and its relationship with his baseball profession are examined in this article.2

The Sport of Trapshooting

Trapshooting has been part of America’s sports scene since the late nineteenth century. In it, people shoot at targets—typically with a 12-gauge shotgun—launched into the air by a machine in a direction away from the shooter. The targets are saucer-shaped pieces of baked clay, from which the name clay target is taken. The sport was designed originally to allow bird hunters to practice their skills by shooting at clay targets instead of live pigeons; hence, another oft-used name for the target is clay pigeon. The machine moves continuously to change the angle at which a target is sprung from the trap, providing more realism in simulating bird hunting. Competition among participants involves shooting from a fixed position at a pre-determined number of targets over one or more rounds. Whichever competitor “breaks” the greatest number of targets is the winner.3

Trapshooting achieved considerable popularity throughout America by the early twentieth century. In 1915, there were over 4,000 trapshooting clubs in the nation with more than a half million members.4 Still, trapshooting struggled against an image of being a “rich man’s game” intended for the well-to-do. Only the wealthy, it was widely believed, could pay for trapshooting club memberships, a high-quality shotgun, copious amounts of ammunition and targets, and the fees attendant to match competitions.5

Baseball and Trapshooting: A Synergistic Relationship?

Executives from the business side of trapshooting (e.g., arms and ammunition manufacturers, gun club owners, etc.) sought to entice more Americans to spend time and money at the traps by promoting the theme that the sport was a fitting pastime for the common man. Baseball became an integral part of this campaign. Every American—not just affluent ones—should embrace trapshooting, it was claimed, because of the similarities to the National Game, a supposition demonstrated by the many professional ballplayers who were trapshooters. It was a simple proposition: If you enjoyed baseball, you would enjoy trapshooting.

Articles on trapshooting in the early twentieth century often trumpeted the large number of major leaguers who favored shooting during the offseason. A number of eventual Hall of Famers were identified as avid trapshooters, including Christy Mathewson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Chief Bender, Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Roger Bresnahan, and Frank Baker.6 The author of one article asserted that “virtually every player of prominence” also was a trapshooting enthusiast, and he noted more broadly:

A recent canvass of every player of note showed that forty-nine out of every fifty owned shotguns—some of the players being the owners of more than one gun while several had equipments of five guns, and one boasted of seven guns. Further, all claimed that shooting was their favorite sport.7

Several reasons were offered to explain the affinity ballplayers had for trapshooting. The most prominent was that the sport kept abilities needed on the diamond sharp during the offseason.8 One writer professed, “For shooting and baseball are two of America’s “best bets” in the sports world. Both require a steady nerve, good eye, even temperament, concentration, and A-1 brand of sportsmanship. Indeed, they have many things in common.”9

A sports columnist echoed this refrain in a 1915 article that noted once the baseball season had ended, players instinctively headed for the traps:

Trapshooting has taken such a strong hold upon the players in the past two years that they have now resolved themselves into a series of exchanges of the bat, ball and glove for the gun and shell. They have found from experience that trapshooting is the only recreation for their Fall and Winter period of idleness that will not send them into next season’s campaign overtrained.10

The particular advantage hours spent on a firing line at a trapshooting club had for pitchers was emphasized in one article: “The clay bird game is a sport that, more than any other, keeps eyes keen, steels the nerves and cultivates instant and accurate judgment of speed, distance, the effect of wind, etc.; things that are invaluable to a pitcher.”11

The campaign to attract baseball fans to the traps went beyond highlighting that numerous major leaguers enjoyed the sport. Proponents of trapshooting wanted people participating in the sport, not simply watching it as they did baseball games. Trapshooting had not developed into a spectator sport, and industry officials realized the unlikelihood of convincing people to pay an admission fee to attend matches between trapshooters who, regardless of their skill, were not sports celebrities. While there was ample evidence people would pay to watch famous baseball players participate in shooting matches—as they did to see these same players at the ballpark—the real money was in persuading people to become trapshooters themselves.

Consequently, the allure of the sport was reinforced using the premise that while fans could not compete against ballplayers on the diamond, they could challenge and perhaps even best them in trapshooting competitions. Dangling this prospect served an unmistakable purpose. People were encouraged to see themselves as capable of competing as equals against well-known ballplayers in trapshooting matches. Achieving the talent to contend at this level would, of course, require a significant amount of time and money spent practicing at the traps. But the glory and bragging rights associated with winning such contests were portrayed as powerful inducements to try, including by one author who stressed, “The ‘fan’ is not able to compete with Matty in the pitcher’s box, nor with Cobb at bat and on the bases, but that same fan will gather many crumbs of comfort for himself when he can entice these famous athletes to the traps and show them how to hit the flying targets.”12

The campaign featured other links between baseball and trapshooting with the intent of portraying their shared attraction for ordinary people. Both sports were “truly American” in origin, and “the inherent liking of Americans for baseball and firearms cannot be denied.” In addition, both allowed Americans—living in an increasingly industrialized and urbanized society—to nostalgically relive the country’s pastoral and bucolic past. Baseball and trapshooting took place in the “Great Outdoors,” permitting participants and even those just watching the competition to bask in sunshine, breathe fresh air, enjoy simple pleasures, and escape the stifling oppressiveness and regimentation of the office, the factory, and—for children—the classroom.13

While the many ballplayers shooting at the traps lent credence to the claim that it was a popular sport among major leaguers during the offseason, match competition specifically was cited as the clearest evidence ballplayers—especially stars—believed trapshooting benefited their skills on the diamond. And of all of those who excelled at the ballpark and at the traps, it was Chief Bender who—by combining his baseball talents with his shooting skills—substantiated most convincingly the claim that because both sports are complementary, success in one contributed to success in the other.

Chief Bender the Ballplayer

A sizable body of literature exists on Chief Bender’s career in professional baseball; therefore, his record as a major leaguer is only summarized here.14 Bender pitched for manager Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics 1903–14. He was a key member of the A’s “First Dynasty,” which won four American League pennants and three World Series championships, 1910–14.15 Mack considered Bender his “greatest one-game pitcher,” and was quoted as saying, “If everything depended on one game, I just used Albert, the greatest money-pitcher of all time.”16

Bender signed with the Baltimore Terrapins of the Federal League for the 1915 season, and he ended his active major league career by pitching for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1916–17.17 By the time he hung up his spikes, Bender had won 212 games, posted a .625 winning percentage, and pitched a no-hitter. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953—the first Native American accorded that honor. Although informed of his selection, Bender did not live to see his induction into the Hall. The ceremony took place on August 9, 1954, almost three months after his death on May 22, 1954.18

Chief Bender’s Views on Trapshooting

In an interview that appeared in the April 1915 issue of Baseball Magazine, Chief Bender explained his partiality for trapshooting:

I have been shooting clay targets for about thirteen years and with every visit to a trapshooting club the hold of the sport on me grows…It would be pretty hard to give the biggest reason why trapshooting appeals. There are so many reasons and almost any combination of these reasons would hold a man in the game once he had experienced the fascination of shattering a clay saucer that was getting away from him at a rate that made a bird’s flight look lazy…Perhaps you have already suspected it, but to make sure that there be no mistake about it, let me tell you in plain English: I am a gun bug.19

In a short article that appeared under his name that same year, Bender echoed the notions of trapshooting’s popularity among ballplayers, and how it enabled them to keep their baseball skills sharp during the offseason:

Like 95 percent of the baseball players and fans, I find my chief recreation away from the diamond in the gun…I believe the one sport is the complement of the other. It seems to me that all of the baseball fraternity realizes that the one sport or hobby that is necessary to them in the offseason of baseball is shooting…The practice at the traps not only provides a certain amount of physical exercise, but it also trains the eye and mind, develops self-control, and brings the player into close communication with the best type of sportsmen in the world.20

Bender’s relationship with trapshooting, however, was more multifaceted than simply using it as part of his training regimen during the offseason. He was aware of the considerable financial rewards winning match competitions could yield, and that realization as much as any other influenced his affinity for the sport and beckoned him frequently to the traps.

Trapshooting as a Money Sport

Trapshooting was covered extensively in newspapers and sports periodicals during the first decades of the twentieth century when Chief Bender was active in the sport. Sporting Life, for example, included a section, “The World of Shooting,” and a column, “Those Shooters We Know,” which reported in each issue on the results of matches including those in which Bender competed.21 It is from this coverage that we can gain an understanding of the extent of his participation in shooting contests, monetary prizes at stake, and the success Bender enjoyed on the firing line.

Trapshooting competition typically took place in one of four formats:

- An individual match in which shooters competed one-on-one. Both wagered identical sums that became the purse.22 They fired at a specified number of clay saucers, and whoever broke the most targets was the winner. The amount wagered by a shooter in an individual competition was seldom less than $50.

- Tournament play, consisted of multiple shooters—usually between 10 and 20—each paying an entrance fee to participate in the competition. Total fees paid, which typically varied between five and twenty dollars for each entrant, became the purse. The winner again was determined by who broke the greatest number of clay birds, although tournaments didn’t always use the winner-take-all format. Instead, the purse was divided between the first- and second-place finishers.

- A variation of tournament play featuring the “miss-and-out” match. Participants would each shoot at 10 clay birds per round. The first time a shooter missed a target, he was eliminated from the contest. The competition continued until only one shooter was left standing.

- Team contests involving multiple shooters—typically three to five in number—competing together against an equal number of shooters on another team. Each team’s collective total of clay pigeons struck determined the champion, and members of the victorious team divided the winnings equally.

Exact contest purses are in many cases not specified in reporting on trapshooting matches. There are instead references to “big money,” “big purse,” and “neat sum of money.” Enough references to specific amounts exist, however, to gain a good understanding of the amounts at stake.

Chief Bender and other ballplayers in a circa 1915 photo taken at the Beideman Gun Club—Bender’s home range—in Camden, New Jersey. From left: Chief Bender, Fred Plum—National Amateur Trapshooting Champion—Grover Cleveland Alexander (Phillies), and Joe Bush (Athletics). (Author’s Collection)

Purses varied significantly among competitions. For example, in a March 3, 1909, match, Bender and his opponent, S. White, each put up $100 to shoot at 50 targets. Bender broke all of them while White could manage to hit only 43.23 In another match held “in a driving rain” on February 23, 1909, Bender and Nathan Benner engaged in a 50-target contest. Bender cracked 44 clay birds against Benner’s 43 and took home $375.24 Not all purses were so rich. In other individual contests in which Bender participated, the amount bet by each shooter was $50.25

Winnings in the tournament format were determined by the number of participants and the entrance fee.26 For example, Bender participated in a 1909 competition in which 12 participants each paid ten dollars to shoot. Bender won “first money” by cracking 24 of 25 clay birds.27 In a match the previous year in which 15 participants paid $5 each to shoot at 10 targets, Bender came out on top by downing all 10 birds.28

The totality of reporting on Bender’s prowess as a trapshooter reveals he won, or at least finished “in the money,” considerably more often than he did not. But Bender was not always victorious.29 A match in 1915 paired him against Lt. George Marker of the Pennsylvania Railroad police for the handsome sum of $500. In an unusual twist, the contest was not held at a gun club, but at the Charleroi Baseball Park in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. Presumably, this was done to accommodate more spectators who were charged an admission fee to watch the event. Given the amount of money at stake, the number of clay bird targets was set at a modest 25 for each shooter. Marker prevailed by a score of 20 to 16.30

Gambling at Trapshooting Matches

An assessment of trapshooting as a money sport and its relationship with baseball is incomplete without a discussion of gambling. Like other major sports, trapshooting drew gamblers to contests who were there primarily to place bets, not to marvel at the brilliance of outstanding shooters. Depending on the competition format, wagers could be placed in a number of ways: the individual or team that would be victorious; the number of targets a shooter or team would break; the difference in scores between shooters in individual matches or teams in tournament contests; the order in which shooters on a team would finish; and so forth.

Reporting on matches occasionally contains oblique references to gambling since it was illegal—but mostly tolerated—in many places contests were held. Admitting that gambling attracted some people to the traps was contrary to the campaign promoting the sport as a pastoral “truly American” pastime rooted in the “Great Outdoors.”31

Matches that featured baseball stars unquestionably encouraged gambling by attracting larger crowds, but from a business standpoint, the presence of gamblers was an unintended consequence, not a goal. The trapshooting industry wanted people to become trapshooters, not bet on trapshooters, but there is no doubt that the opportunity to gamble on the outcomes of trapshooting contests was a key motivation for many people to attend matches. It wasn’t all about seeing a famous ballplayer in person.

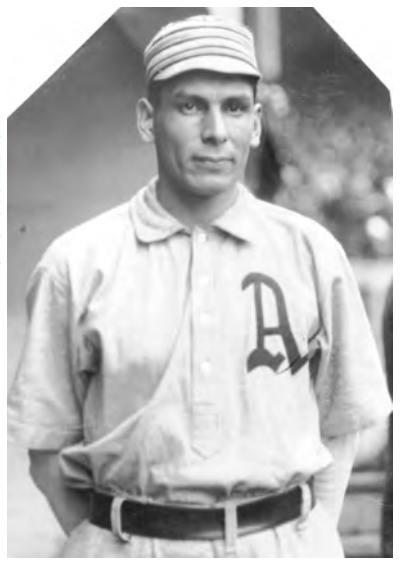

Bender, wearing his A’s uniform in a circa 1910 photo, believed trapshooting helped keep his baseball skills sharp during the offseason. (Author’s Collection)

The typical euphemism used to acknowledge gambling at trapshooting events was money “changing hands” among spectators. On rare occasions, however, actual amounts wagered on contests were mentioned in reporting, and that information indicates monies gambled could be huge. For example, in a 1908 two-person match that did not include Bender, “over $6,000 in side bets changed hands.”32 By comparison, the average American worker’s annual salary that year was $700.33

Gambling was not limited to spectators. Shooters often bet on themselves to augment their winnings in matches. This included Chief Bender.

Trapshooting as a Source of Income for Bender: Ballplayer versus Trapshooter

Comparing Chief Bender’s income from baseball versus shooting is hindered by a lack of data on his earnings in both sports. Bender’s salary as a ballplayer is unknown for most years and can only be estimated.34 It is documented he received $5,000 and $4,000 while playing for the Philadelphia A’s in 1911 and 1914, respectively, and reaped his biggest salary of $8,500 while a member of the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins in 1915.35 These were among his highest earnings, and in other years he received considerably less.36

In the same vein, Bender’s trapshooting winnings are in most cases described vaguely with phrases like “a big purse” and “first money.” While specific prize amounts are noted frequently enough in reporting to indicate trapshooting was a financially lucrative sport for those who were successful at it, information on most matches does not include actual purse amounts.

Even with these empirical limitations, some general comparisons can be made between Bender’s incomes from baseball and trapshooting in individual years. For example, following a mediocre performance in 1908 (8–9 record in 17 games started) on an underperforming Athletics’ team that finished in sixth place, an irate Connie Mack sent Bender a contract for 1909 that, according to Mack, “will call for a salary so small that he will no doubt scoff at it.”37,38 Although the exact amount is unknown, given other A’s players’ salaries for that year, Mack probably offered Bender around $1,800.39

The minimal contract tendered to him in 1909 illustrates the significant role trapshooting could play as a second source of income for Bender.40 He knew all too well his pay as a baseball player could go down as easily—perhaps more easily—as it could go up. Mack predicted that when Bender saw the “salary clause in the contract which I will tender him, he will feel like giving up pitching.”41 Bender earned over $1,200 in winning or “sharing in the money” in a mere eight trapshooting competitions that year. This is a base figure because he won additional matches in which prize amounts are not specified in reporting.42 It is highly likely Bender earned more—likely substantially more—in the traps than on the diamond in 1909.

Paid Appearances

Potential earnings from trapshooting were not limited to competing in matches. It is almost certain—albeit unreported, since deals were privately negotiated—that Bender was often paid by gun clubs to appear in contests so large crowds would attend.43 Many spectators were drawn to a match more by his celebrity status than the contest itself. For example, nearly 400 people showed up at the Belmont Gun Club in Narberth, Pennsylvania, to watch Bender shoot against other competitors in a “miss-and-out” tournament in 1909. The event was described as “the biggest shoot ever held by the gun club,” and the large turnout was clearly attributable to Bender’s presence.44 That same year, Bender was the “chief attraction” and “continually cheered by a large crowd that had assembled to see the Indian shoot” in a match held in Morrisville, New Jersey.45 Gun club owners eagerly hoped those who came to see Bender might be intrigued enough with the sport to take up trapshooting themselves.

Betting on Himself

A 1909 article in the Washington Post stated that Bender bet on himself to win trapshooting matches.46 Given the prevalence of gambling surrounding the sport, it is not surprising he engaged in the practice. Wagers probably were made with other shooters and attendees. No data exist on how often he gambled on himself at contests or the financial gains he secured by doing so, but it is virtually certain he came out ahead, given his talent as an exceptional marksman and how frequently he was victorious in shooting contests.

Endorsements

Chief Bender’s domination among ballplayers as a marksman afforded another opportunity for earnings—endorsing products. From the nineteenth century through today, baseball players—especially stars—have endorsed products for a fee. Bender was no different, and some of the merchandise he backed was associated with trapshooting. These included appearing in a Du Pont Gun Powder Company advertisement extolling the “irresistible fascination” of the traps, and another for the company promoting the superior performance of Du Pont’s “Hand Trap,” used to hurl clay pigeons into the air.47 In addition, Bender touted the quality of U.M.C. Arrow shotgun shells, and publicized the Parker shotgun, which he “uses in all his contests.”48

Bender also parlayed his celebrity status as a ballplayer and trapshooter into employment during the offseason as a salesman/consultant for sporting goods and other merchandise in Philadelphia-area department stores. Early in his career, he was employed in that capacity by Wanamaker’s Department Store, and after his baseball career by Gimbels Department Store.49

While Bender wrote about the intrinsic joy of trapshooting and its beneficial effects on his baseball abilities, the multiple ways the sport augmented his income motivated his drive for excellence and participation in shooting competitions. It also was not lost on Bender that trapshooting could be a profitable source of income for him long after his days as a major league ballplayer had ended.

The Vaudeville Pause

Chief Bender was actively involved on the shooting circuit when not on the baseball diamond throughout his major league career save one year—1911. An article in Sporting Life reported:

Chief Bender, the wonderful Indian pitcher of the World’s Champions Athletics will not be able to indulge in any shooting this Fall and Winter, as he is booked clear through the offseason in vaudeville. Chief is one of the best live bird shots in the country and an extremely good target shot. He had planned to shoot some big matches this season, but the theatrical engagements prevent.50

The vaudeville sketch was called “Learning the Game,” and it featured Bender along with fellow Athletics’ pitchers Cy Morgan and Jack Coombs.51 Cornball humor dominated the act, which took place in a garden supposedly outside Shibe Park. In Bender’s big scene, he would be dressed in an A’s uniform to play the role of a “bashful Chippewa” by the name of “Strong Heart.” Upon leaving the ballpark, Strong Heart encounters a young lady who knows almost nothing about baseball. She strikes up a conversation: “I hear you pitched a great game against the Giants today.” Bender’s reply: “Oh, yes, but Larry Doyle hit me twice.” Believing he had been physically assaulted, the horrified woman asks, “Why?”52

Another scene in which all three pitchers appeared had them showing the audience how they held a baseball to throw their signature pitches. Morgan demonstrated throwing “the spitter,” Coombs followed with his celebrated curve, and Bender finished up by displaying how he performed his knuckle delivery. A stage hand did the catching.53

But in vaudeville, as elsewhere in is life, Bender suffered indignities rooted in the prejudice and discrimination that permeated American society in the early twentieth century.54 When the act was playing in Atlantic City, Bender, Coombs and Morgan were in the lobby at Young’s Hotel waiting to cross the boardwalk to perform at the Steel Pier. A “southerner” who was staying at the hotel saw Bender and demanded of manager Jimmy Walsh to know if he was a guest. Walsh acknowledged he was and inquired, “What’s the matter?” The man observed Bender was “a person of color” and declared, “I won’t stop at a place like this!” Walsh replied, “Why that man’s an Indian. He’s Chief Bender of the World Champion Athletics. The best is none too good for him.” Astonished, the man adjourned to the bar, but whether he stayed or departed for another hotel is not known.55

A circa 1917 photo of Chief Bender holding the tool of his trapshooting trade. (Author’s Collection)

Encounter with Annie Oakley

While the Philadelphia Athletics were conducting spring training in New Orleans in 1908, several players—Chief Bender, Jack Coombs, Doc Powers, Eddie Plank, and Simon Nicholls—spent one morning at the shooting range where Bender and Coombs cracked over 90 percent of their targets. That afternoon during an exhibition game between the A’s and the New Orleans Pelicans, famous sharpshooter Annie Oakley appeared and took in the game. Unfamiliar with baseball, she was tutored by Coombs on its finer points. One of the questions she asked was why Athletics’ players on base didn’t try to score when a foul ball was hit over the grandstand, believing they could do so while the ball was retrieved and brought back into the ballpark.56

Although Bender and Oakley met on this day—their only recorded meeting—they did not engage in a shooting contest. It would have been a memorable moment for the sports of trapshooting and baseball to have had them compete against each other.

Ballplayers’ Trapshooting Trip

The highpoint of the baseball-trapshooting relationship during Bender’s era came following the 1915 season when the Du Pont Gun Powder Company decided to sponsor a three-week tour by a squad of baseball stars to compete against the best shots at gun clubs in the East and Midwest. The purpose of the trip—and Du Pont’s goal in sponsoring it—was to attract more people to become trapshooters:

The participants in this tour will be a group of prominent major league baseball stars, men of wide repute in the field, but also skilled as trapshooters. They plan to travel from the Atlantic half way across the continent, shooting in the leading trapshooting centers against the prominent local clubs in the belief that the natural attraction that these stars of the diamond would exert, will bring the sport prominently to the notice of a great army of sportsmen who could easily be brought into the field of the clay target pastime … The trapshooting of such a squad will not only draw the regular shooters, but thousands of baseball fans, who know and admire these players and who may by this means be converts to the sport.57

The ballplayers selected initially for the tour were Chief Bender, Eddie Plank, Harry Davis, and Christy Mathewson. Plank, however, had a son born on October 18 and decided to remain with his family. James “Doc” Crandall replaced him.58 The players’ team was augmented by a “guest” local shooter at each stop.59

A match consisted of 1000 targets. Each five-person team shot at 500 clay birds—100 per man. Whichever team collectively broke the most targets won.60 But in some of the contests, players on opposing teams were also paired individually to expand the levels of competition. For example, when the ballplayers shot against the West End Gun Club in Richmond, Virginia, Chief Bender was paired against E. H. Storr of the club. Bender “walked away with his scalp,” breaking 96 targets to Storr’s 95.61

The tour schedule was rigorous—matches in 18 cities in 20 days. Table 1 shows the November dates, gun clubs, locations and results for the players’ team.62, 63

Among the baseball players, Bender was called “the star of the group.”64 During the tour, each player shot at 1800 clay birds—100 targets per player at each of 18 stops. Bender claimed top spot by breaking 1658 of them. Crandall downed 1287, while Mathewson followed closely behind at 1285.65 Davis finished last with 1232.66

Although the players lost far more often than they won, the tour was an enormous success from the perspectives of sponsor Du Pont and the gun clubs that hosted the matches. Reports from throughout the trip highlighted the extraordinary number of people who came to witness the competition, many of whom had never before set foot on a trapshooting range. Examples include:

- The visiting squad of baseball players drew a great gathering of spectators to the West End Gun Club on November 8, the crowd being the largest that has ever attended a shooting event in this city. (Richmond match)67

- The interest manifested by the baseball shooters is very satisfactory. Large delegations from Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and the down-State shooters of Missouri were present. The baseball fans were also much in evidence, playing their favorites off the boards. (Kansas City match)68

- A gallery of more than 400, including many women and baseball fans, was on hand early… The presence of the ballplayers attracted a large number of marksmen from New Hampshire and Maine. (Boston match)69

A Sporting Life article written after the tour emphasized its success, and concluded the endeavor had achieved its intended purpose:

One of the most successful trapshooting promotion trips undertaken in recent years came to a close on Saturday, November 27, in Boston, when the team of touring major league baseball players competed against the Paleface Gun Club combination…Along the entire route the shooters were greeted not only by trapshooters, but also by thousands of baseball fans who were interested in the players, but who had never seen a trapshooting event. Needless to say, many of these have now been inoculated with the trapshooting germ, which will make them lovers of the sport for life, and the Du Pont Powder Company, the sponsors of the trip, deserve unlimited credit for the benefit of the sport.70

How much the players were compensated for their involvement in the trip—in addition to expenses—is not revealed in reporting on the event. They themselves expressed delight at how well they were treated—for example, a large banquet was held in their honor at every stop—and there was speculation a second trip would be planned for 1916.71

Trapshooting in Bender’s Life

As his baseball career wound down, Bender continued to be active in trapshooting circles. During the winter of 1916–17, he engaged in several matches with other Philadelphia-based baseball players. In a contest staged at the Whitemarsh Country Club, Bender bested fellow pitcher Joe Bush in a 50-bird shoot, 50 to 46. In another match of 500 clay targets a side, Bender teamed with Phillies’ catcher Billy Killefer against the team of Bush and Grover Cleveland Alexander. On this occasion, in reporting that gratuitously highlighted Bender’s heritage, “Bush’s team beat the Indian’s team 420 to 403.”72

Late in life, Bender evinced some regret that he had not focused more on developing a second career in business while he was performing in the major leagues.73 In an interview with J.G. Taylor Spink months before he died, Bender observed:

Practically all I did was hunt and fish, but in those days it was not impressed on our minds that we should prepare ourselves for the future. Today all the fellows are interested in learning or lining up some business for the time when they can no longer play.74

And in a departure from his perspective of 40 years earlier that trapshooting was the finest sport for ballplayers to pursue when not on the diamond, he advised, “One thing that always helped me though, and I think it would help every pitcher without taking too much time, is bowling. You’d be surprised how it keeps the legs in shape, and the arm and shoulder muscles loose.”75

Bender’s lamentation about not planning ahead more fastidiously for his financial future probably was prompted by the serious money issues he experienced later in life. When “Chief Bender Night” was held at Shibe Park in 1952, he was given a check for over $6,000 because Bender needed money more than expensive gifts like a car or vacation trip to some exotic location.76

While Bender’s pecuniary problems adversely affected his later years, they in no way diminish his remarkable accomplishments on the mound and at the traps earlier in life.77 He was the finest marksman among active major league players of his day, a fact acknowledged by The American Shooter magazine when it named him “King of the Ballplayers at the Traps” in 1916.78,79 The extraordinary recognition he received in being inducted into a Trapshooting Hall of Fame as well as the National Baseball Hall of Fame is further proof of the breadth and impressiveness of his achievements.80

Success in both sports enabled Chief Bender to transcend being a talented ballplayer and an expert shooter. Together, they made him a true sportsman, which Bender probably would have regarded as the greatest honor of all he could have been accorded.

ROBERT D. WARRINGTON is a native Philadelphian who writes about the city’s baseball history.

Notes

1. “Ball Players Hit ’Em With a Gun,” The American Shooter, January 1, 1916. The article notes ballplayers also enjoyed hunting as an offseason recreational activity.

2. Trapshooting and trapshooter can be spelled as one or two words. In this article, both are spelled as single words. In the early twentieth century, baseball and ballplayer were spelled as two words, as they were in several quotations used from that period in this article. For the sake of consistency, both are spelled as one word, including when they appear in those quotations.

3. Trapshooting has evolved dramatically since the days of Chief Bender. In addition to trapshooting, there are now different disciplines of clay target shooting, including skeet shooting and sporting clays, and even further variations within each of those categories. The targets themselves are made of other materials in addition to clay. To learn more about the history and evolution of trapshooting as a sport in the United States and around the world, see, “Trap Shooting,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Trap_shooting. For more details about the rules and technical specifications of trapshooting, see, http://www.craigcolvin.com/photogrsaphy/ index.php/what-is-trapshooting.

4. Pennsylvania led all states with almost 400 clubs. Men dominated the sport, not surprisingly, but women also were counted among the ranks of trapshooters. Wilmington, Delaware, had the largest women’s club—the Nemours—and the largest men’s club—the Du Pont—based on membership. Women preferred shooting at targets hurled into the air by hand rather than by a mechanical arm on a machine—the former requiring less skill of the two techniques. Samuel Wesley Long, “What is the National Sport,” Baseball Magazine, June 1915.

5. The longstanding campaign to expunge the perception of trapshooting being largely confined to the affluent is acknowledged in “The Shooting Game,” www.clearleaderinc.com/site/shooting-game.html. That trapshooting began and remains a sport reserved for the rich who can afford it is asserted in, www.trapshooting.com/threads/shooting.

6. American Shooter, January 1, 1916.

7. Long, Baseball Magazine, June 1915. Other than citing “a recent canvass,” Long provides no information about how the survey was done, by whom, which ballplayers participated, and how the questions asked were phrased. Long acknowledged that not every ballplayer who owned a shotgun was a trapshooter, but using a somewhat torturous line of reasoning, argued that all owners “are interested in trapshooting from a very personal standpoint because of familiarity with the shotgun, the principal accessory of the sport.” Even if most major league ballplayers possessed firearms at that point in time, the accuracy of the claim that “forty-nine out of every fifty players owned shotguns” is impossible to verify empirically.

8. The veracity of this claim is open to question. While some Hall of Fame ballplayers were avid trapshooters, others were not. Moreover, some ballplayers who also were ardent trapshooters do not reside in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Harry Davis, Otis Crandall, Jack Coombs, George Stallings, Nap Rucker and Jake Daubert. That offseason shooting was advantageous to performance on the diamond is an argument built through assertion, not empirical evidence and logical argumentation. While it is not unreasonable to believe trapshooting afforded some benefits to players who engaged it in during the offseason, and certainly was preferable to staring out the window and waiting for spring—to quote Rogers Hornsby—the same could be said of other sports like tennis and bowling. It will never be known if those who became Hall of Famers would have performed less capably on the diamond had they not been fervent shooters in the offseason. American Shooter, January 1, 1916.

9. Ibid.

10. Thomas D. Richter, “Baseball Players as Shooters,” Sporting Life, November 6, 1915.

11. Samuel Wesley Long, ““Chief” Bender Goes Back to Organized Baseball,” Baseball Magazine, April 1916.

12. American Shooter, January 1, 1916. Another article with a similar theme noted that comparatively few men play baseball at the major league level while thousands of spectators watch. As a sport, trapshooting is much more egalitarian because it permits a far greater number of people to compete in matches—including against major leaguers—instead of being relegated to the passive role of observer, as in baseball. Long, Baseball Magazine, June 1915.

13. Long, Baseball Magazine, June, 1915. While enchanting, these assertions are dubious and cannot be accepted at face value. Fans attending games at ballparks located in major cities breathed the same air as the rest of the people who lived there. Ballpark air wasn’t less polluted. This fact is highlighted by the Reading Railroad tracks that ran across the street from the Phillies’ National League Park. Billowing smoke and embers from passing locomotives would come down on patrons in the stands—hardly the fresh air of the “Great Outdoors.” Rich Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 29. As far as baseball being “truly American” in origin, the Mills Commission report that baseball was a purely indigenous American sport invented by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York, in 1839 has long been discredited. Baseball is in part derived from the English games of rounders and cricket. G. Edward White, Creating the National Pastime (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 122–25.

14. Tom Swift, Chief Bender’s Burden: The Silent Struggle of a Baseball Star (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008). William C. Kashatus, Money Pitcher: Chief Bender and the Tragedy of Indian Assimilation (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006).

15. David M. Jordan, The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901–1954 (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 1999), 30, 42–62.

16. Associated Press Biographical Service, “Biographical Sketch of Charles Bender” (May 15, 1942), Bender file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library, Cooperstown, New York. Mack always referred to Bender and addressed him personally using his middle name, “Albert.”

17. Chief Bender pitched a single inning in a game in 1925 while working as a coach for the Chicago White Sox. The team was managed by his friend and former A’s teammate Eddie Collins, and Bender’s appearance on the mound was primarily a stunt. The Sox were playing the Boston Red Sox that day, the team Bender had beaten to gain his first major league victory in 1903. Tom Swift, “Chief Bender,” Baseball Biography Project, http://bioproj.sabr.org.

18. After retiring as a major leaguer, Bender spent many years pitching, managing, and coaching in the minor leagues. His last job was as a pitching coach with the Philadelphia Athletics. http://www.thebaseballpage.com/ player/bendech01/bio.

19. “What a Famous Pitcher Thinks of Trap Shooting,” Baseball Magazine, April 1915.

20. Chief Bender, “Ball Players as Shooters” (March 6, 1915), Bender file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library, Cooperstown, New York.

21. Bender’s home trapshooting facility was the Beideman Gun Club in Camden, New Jersey. He trained there, put on shooting exhibitions and participated in matches sponsored by the club. “Baseball Players Thrive as Trap Shots,” Sporting Life, April 7, 1917. In a display of his shooting prowess at Beideman, Bender once went through 100 targets without a miss and broke 38 more in a row before a saucer finally got by him. A reporter who watched the demonstration called it “one of the most remarkable exhibitions of trapshooting ever seen in this section of the country.” “Bender Breaks 138 Straight,” Sporting Life, February 13, 1915.

22. Sometimes, gun clubs would put up the purse to attract sports celebrities to the range in hope of drawing a big crowd to watch them shoot. If spectators were charged an admission fee, the purse could be “sweetened” by adding to it a percentage of gate receipts. In either case, persuading people to attend a match so they might become trapshooters themselves was the ultimate goal of the club owners.

23. Thomas S. Dando, “Those We Know,” Sporting Life, May 22, 1909. Two months earlier, White had challenged Bender to a contest for the same stakes, that time shooting at live pigeons instead of clay birds. Bender obliged and shooting “in his best form,” according to a report describing the event, walked away with another $100 of White’s money. Thomas S. Dando, “Those We Know,” Sporting Life, March 13, 1909.

24. Thomas S. Dando, “Those We Know,” Sporting Life, February 20, 1909. Dando reported the results of the contest in his column that appeared in the February 27, 1909, issue of Sporting Life. In this case, Bender also received a portion of the “gate receipts” for winning, but the amount is not specified.

25. In a 1909 match at the Rod and Gun Club in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Bender cracked 19 of 20 birds “and walked off with $50 of the money.” Sporting Life, February 13, 1909. Bender won the same sum defeating A.A. Felix in a live bird shoot at the Point Breeze Gun Club in Philadelphia in 1907. Sporting Life, January 4, 1908.

26. Occasionally, a gun club would offer a special prize to the winner of a match in addition to the purse. In a 1908 tournament competition held at the Penrose Gun Club in Philadelphia, Bender won a shotgun in addition to first-place money. “The Live Bird Shooters of Philadelphia Enjoy the Holiday,” Sporting Life, January 2, 1909.

27. “Bender’s Honors,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1909. The article does not specify the amount Bender won, but based on the division of winnings in other tournaments held during the same period, he likely received two-thirds of the purse, with the second-place finisher taking home one-third.

28. “Bender a Winner,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1908.

29. In early 1915, Bender engaged in a 100-bird match with Carroll W. Rasin, president of the Baltimore Federal League Baseball Club, with whom Bender had signed to play that season. Rasin won by the razor-thin margin of 89 to 88. One can only wonder if Bender let him win as a courtesy to his new boss. “The World of Shooting,” Sporting Life, February 13, 1915.

30. “Those Shooters We Know,” Sporting Life, October 16, 1915. The match was announced in an article in Sporting Life, October 2, 1915. Why both men, especially Bender, shot so poorly is not explained. It may have had something to do with the unusual setting for the contest—a baseball park—and/or the weather.

31. Gambling in trapshooting also raised the prospect of matches being fixed by those willing to bribe participants to bet on a “sure thing.” The extent to which, if at all, fixed trapshooting contests were a problem in the sport is beyond the scope of this paper, but none of the research completed by this author uncovered any allegations or evidence that competitions were anything other than honest.

32. “Roughton Outshoots Benner,” Sporting Life, February 29, 1908.

33. Meryl Baer, “The History of American Income,” eHow, http://www.ehow.com/info_7769323_history-american-income.htm (accessed September 14, 2016). To make a further comparison, major league baseball’s highest paid player in 1908, Cleveland’s Nap Lajoie, earned $8,500. See Michael Haupert, “MLB’s annual salary leaders, 1874–2012,” at SABR.org, http://sabr.org/research/mlbs-annual-salary-leaders-1874-2012 (accessed September 14, 2016).

34. For the 16 years Bender pitched in the major leagues—including his one-game stint in 1925 with the White Sox—his salary is reported for five years (1903, 1911, 1914, 1915 and 1925), and is “undetermined” for the other 11 years. http://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/ player.php?p=bendech0.

35. Ibid.

36. Kashatus, Money Pitcher, 111, 125–26.

37. Jordan, Athletics of Philadelphia, 40–41.

38. Thomas D. Richter, “Philly Jogged,” Sporting Life, February 27, 1909. Bender grudgingly accepted Mack’s parsimonious offer. Kashatus, Money Pitcher, 111.

39. If accurate, this would have been only $600 more than Bender received when he first signed with the Athletics in 1903. http://www.baseballalmanac.com/players/player.php?p=bendech0.

40. Mack probably had an ambivalent attitude toward Bender and trapshooting. He understood Bender’s affinity for the sport, recognized his ascendant talent as a shooter, and appreciated how competing augmented his yearly income. Indeed, in 1908, Mack gave Bender a week’s vacation during the season to attend the Pennsylvania State Championship Shoot in Bradford, Pennsylvania. At the same time, Mack would not permit any outside activity, regardless of its profitability, to interfere with a player’s commitment to the Athletics and maintaining peak performance on the diamond. Mack’s willingness to let Bender attend the state championship competition is described in, “Those We Know,” Sporting Life, May 30, 1908.

41. Richter, Sporting Life, February 27, 1909.

42. Sporting Life, various issues in 1909.

43. A gun club’s desire to downplay compensation for Bender, or any ballplayer, to compete in a match or shoot in an exhibition is certainly understandable. A club wanted to promote the belief the player was there because of his intrinsic devotion to the sport—a passion spectators also could experience by becoming involved in trapshooting. Acknowledging a player was paid to appear was inconsistent with that image.

44. Bender came in second place but still “shared in the money.” “Chief Bender Fell Down on Ninth Bird at Belmont,” Sporting Life, February 6, 1909.

45. “Kills 19 Straight, Pitcher Bender is Chief Attraction at Morrisville Shoot,” Sporting Life, January 23, 1909.

46. A reference to the June 6, 1909, edition of the Washington Post edition noting Bender wagered on himself in trapshooting contests is contained in Swift, Bender’s Burden, 303.

47. The Du Pont advertisement on the attraction of trapshooting as a sport appears in Sporting Life, April 10, 1915. The Du Pont advertisement publicizing the company’s “Hand Trap” is found in Sporting Life, May 22, 1915.

48. The reference to using U.M.C. Arrow shotgun shells is contained in an article describing a trapshooting match Bender won. Sporting Life, May 22, 1909. That Bender used a Parker shotgun for shooting competitively is featured in an article describing his abilities as a marksman. “Those We Know,” Sporting Life, February 25, 1908.

49. Bender’s employment with Wanamaker’s is mentioned in Kashatus, Money Pitcher, 140, and his job with Gimbels in Swift, Bender’s Burden, 278.

50. Thomas D. Richter, “In Re Shooters,” Sporting Life, November 11, 1911.

51. The selection of Athletics’ players to appear in the show was no doubt influenced by the fact the club had won back-to-back World Series championships in 1910–11.

52. A reporter who described the act noted, “The dressing room made him (Bender) appear lighter (in skin tone) than he really is.” “Stars Every Way,” Sporting Life, November 18, 1911. The choice of the Giants in the sketch dialogue is odd since the A’s did not play that club during the regular season. It probably was a reference to the just-completed 1911 World Series in which the Athletics defeated the Giants.

53. Ibid. The real star of the show among the ballplayers was Cy Morgan who had experience in vaudeville and, according to this article, “was a big hit with his song numbers.”

54. In addition to describing his baseball career, the biographies of Bender by Kashatus and Swift cited earlier assess the injustices he experienced as a part-Chippewa American Indian occupying the high-profile position of major league pitcher in a racially intolerant society. Bender is habitually identified as an “Indian” pitcher in Sporting Life reporting on his trapshooting exploits, although the race of other baseball players is never mentioned, presumably because they were all white. Bender made it clear he wanted to be presented to the public as a pitcher, not as an Indian. Newspapermen chose to ignore this request. Swift, Bender’s Burden, 4.

55. According to the article in which this anecdote appears, the southerner did not actually call Bender a “person of color,” but “used entirely different words” that Sporting Life chose not to repeat in print. It is not for this author to speculate what bigoted term was uttered. “This Was Different,” Sporting Life, November 25, 1911.

56. Thomas A. Marshall, “Marksmen in Dixie Land Heartily Welcome Experts at Various Points—Shoot with Ball Players—Incidents of Tour,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1908.

57. Thomas D. Richter, “Ball Players Follow Shooting Circuit,” Sporting Life, October 16, 1915. Bender, Plank, and Crandall played in the Federal League during the 1915 season. Mathewson was with the New York Giants, while Davis was a coach with the Athletics, although he did appear in five games with the team that year. www.baseball-reference.com/players.

58. “Stars Added to Ball Players’ Trap Shooting Trip,” Sporting Life, October 23, 1915.

59. Why a local shooter was added to the players’ team at each stop instead of using five players throughout the tour was not explained. It is possible that doing so heightened the level of competition since the local shooting team would not only be competing against famous ballplayers but also one of their own.

60. “Players Ready for Shooting Trip,” Sporting Life, November 6, 1915.

61. “Ball Players’ Shoot Tour a Success,” Sporting Life, November 20, 1915. The metaphor of Bender taking Storr’s scalp is a derogatory reference to Bender’s Indian heritage. Another example of a disparaging reference to Bender’s Indian heritage is an article that reported Bender was “on the warpath against clay pigeons.” “Trap Gossip,” Baseball Magazine, December, 1916.

62. All of the information on the tour is taken from the following issues of Sporting Life: October 16, 23, 30, 1915; November 6, 20, 27, 1915; and, December 4, 1915.

63. For reasons that are not clear, Sporting Life did not print the results of the matches held in Toledo on November 22 and Syracuse on November 24. The January 1, 1916, issue of American Shooter lists the scores of each player at every stop on the tour, including those in Toledo and Syracuse, indicating the matches were held.

64. Richter, Sporting Life, November 6, 1915. There were added bonuses for being the best shot. In Chicago at the Lincoln Park Gun Club, for example, Bender received a gold medal for marksmanship in striking 95 of the targets. Sporting Life, December 4, 1915.

65. Following the tour, Mathewson was quoted as saying, “Chief Bender is one of the best trap shots I ever saw.” “Mathewson on Shooting,” Sporting Life, December 18, 1915.

66. American Shooter, January 1, 1916. As noted in footnote 53, this article contains a table showing the number of clay pigeons broken by the four players individually in each of the 18 matches. Mathewson did not participate in the contest in St. Louis, Missouri. His total was calculated by averaging his score over the other 17 matches and adding that figure to his total number of birds hit.

67. Sporting Life, November 20, 1915.

68. Sporting Life, November 27, 1915.

69. Sporting Life, December 4, 1915. Note the emphasis in the reporting on the ballplayers’ presence being more influential in attracting a large crowd than the match, itself.

70. Ibid.

71. Sporting Life, November 27, 1915.

72. Sporting Life, April 7, 1917.

73. The Bender file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame includes a 1915 newspaper advertisement for the Chief Bender Sporting Goods Company located at 1306 Arch Street in Philadelphia. According to the advertisement, “The Chief knows what’s what in baseball and baseball toggery! Everything you get here you can bank on will be O.K. Suits, bats, balls, gloves, shoes, accessories! Best of quality throughout. Prices are right. Glad to give suggestions. Come in and talk it over.” Bender file. National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library, Cooperstown, New York. Bender’s store is referenced in Kashatus, Money Pitcher, 140.

74. J.G. Taylor Spink, “Looping the Loop,” Sporting News, December 30, 1953. There were occasional references to Bender going into business following his baseball career and his continued participation in trapshooting competitions. An early 1917 Sporting Life article noted, “However, there is a possibility Bender will retire from baseball and go into business this season in which event he will shoot in the Pennsylvania State Tournament next May and will be one of the favorites for the individual championship.” Bender played for the Phillies that year, his final regular season as a major leaguer. “News Notes of Trapshooting,” Sporting Life, January 6, 1917.

75. Spink, The Sporting News, December 30, 1953.

76. Swift, Bender’s Burden, 278.

77. A noteworthy shooting episode that did not occur at the traps involved Bender downing a vulture in 1907 while the team conducted spring training in Texas. The bird had been hovering over the A’s practice field when Bender brought him down with a rifle, explaining his action by sayng the club wasn’t so moribund to attract such a creature. The local sheriff heard of the incident and traveled to the Athletics training camp to arrest Bender. It was illegal to shoot vultures, according to the sheriff. It took all of Connie Mack’s diplomacy and persuasive charm to convince the sheriff to let Bender go, assuring him had the pitcher been aware of the prohibition he never would have shot the vulture. Spink, Sporting News, December 30, 1953.

78. Other baseball players attained remarkable success as trapshooters, a noteworthy example of which is Lester German, who pitched for the Baltimore Orioles, New York Giants and Washington Senators from 1890–97. Following his career in baseball, German, an expert trapshooter, toured with the Parker Gun Company and DuPont Company participating in exhibition matches. In 1915, for example, he set a world trapshooting record by breaking 499 out of 500 clay pigeons in a shoot in Atlantic City, New Jersey. While Bender was the better pitcher of the two—German tallied a dismal 34–63 record as a major league pitcher—unlike Bender, German did get to perform in shooting matches with Annie Oakley. www.trapshoot.org/People-Stories/baseball-and-trapshooting.html.

79. American Shooter, January 1, 1916.

80. In the Bibliographical Essay section of his book, Chief Bender’s Burden, Tom Swift notes on page 297 an article dated November 25, 1917, and found in Temple University’s Urban Archives states that Chief Bender and another individual had been recently inducted into the Trapshooting Hall of Fame. The National Trapshooting Hall of Fame website (www.traphof.org) does not list Bender as an inductee, but that Hall of Fame was not established until 1968. It is likely, therefore, that the Hall of Fame into which Bender was inducted was sponsored by a local or state trapshooting organization.