Clemente’s Entry into Organized Baseball: Hidden in Montreal?

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 26, 2006)

This article was selected for inclusion in SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

A lie can travel halfway round the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” Although this quote is often attributed to Mark Twain, at least one Twain researcher claims a different source.1 Beyond the content of the quote, its disputed derivation highlights the need to resist the urge to assume something to be true just because it is repeated often enough or is viewed as “common knowledge.”

A lie can travel halfway round the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” Although this quote is often attributed to Mark Twain, at least one Twain researcher claims a different source.1 Beyond the content of the quote, its disputed derivation highlights the need to resist the urge to assume something to be true just because it is repeated often enough or is viewed as “common knowledge.”

So it is with Roberto Clemente’s sole season in the minor leagues, with the Montreal Royals of the International League in 1954. This saga provides a striking example of a story retold so many times that it takes on a life of its own, eventually becoming so accepted as factual that even a careful researcher may fall into the trap of assuming the claims to be true and not feeling the need to verify them.

Although Clemente spent his entire major league career with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he was originally part of the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. He signed with the Dodgers in February 1954 for a re2ported salary of $5,000 as well as a bonus of $10,000. Rules of the time required a team signing a player for a bonus, including salary, of more than $4,000 to keep him on the major league roster for two years or risk losing him in an off-season draft. Thus, the Dodgers’ choice to have Clemente spend 1954 in the minors meant that they might lose him to another team at the end of the season.3

What has been written about Clemente in Montreal contains a n assertion that th e Dodgers and Royals tried to hide him-that is, play him very little so that other teams wouldn’t notice him. The claim was expressed by Clemente at least as early as 1962 in an article by Howard Cohn in Sport magazine. “Clemente, on the other hand, felt-and still does that the Royals kept him out of the regular lineup so big-league teams would think him a weak prospect and ignore him in the post-season draft for which he’d be available as a bonus player if he4 weren’t elevated to the Brooklyn roster,” wrote Cohn.

Since then, this claim has been trumpeted in much that has been written about Clemente’s entry into organized baseball, including several biographies; one of them, by Arnold Hano, was written during Clemente’s career, in 1968, and revised fol lowing Clemente’s death in 1972; two biographies, by Kal Wagenheim and Phil Musick, were writ ten shortly after Clemente’s death while another, by Bruce Markusen, came out a quarter century later. In early 2006, noted biographer David Maraniss, whose works include Vince Lombardi and Bill Clinton, had a biography of Clemente published.5

The biographers and others who maintain that Clemente was hidden — and beyond that, that the organization may have tried to frustrate Clemente to the point that he would jump the team, making him ineligible to be drafted by another team6 — offer numerous supporting examples. The examples, with few exceptions, turn out to be false.

Decision on Clemente’s Destination

The first question, however, concerns not what happened in Montreal but why the Dodgers did not keep Clemente in Brooklyn in 1954. Many bonus players of this period were kept at the major league level, even though it meant pining on the bench for two years rather than developing in the minors.

As vice president of the Dodgers, Emil “Buzzie” Bavasi had the power to determine Clemente’s fate. In 1955, Bavasi told Pittsburgh writer Les Biederman that the team’s only purpose in signing Clemente had been to keep him away from the New York Giants, even though they knew they would eventually lose him to another team.7

Other explanations offered center around an often cited but never documented informal quota system said to be in effect in the years following the breaking of the color barrier in organized baseball.8 The Dodgers already had five blacks who would play at least semi-regularly on their parent roster in 1954, presumably leaving no room for another player of color. (The claim of an informal quota is another possible myth that has become widely accepted over time. A check of a specific claim made in Wagenheim’s biography — that the Dodgers would never start all five blacks at the same time — is false, and there are other reasons to question the general claim of a quota system, but it is beyond the realm of this article to fully explore the issue.)9

Although Bavasi had claimed at the time that they signed Clemente only to keep him from the Giants, in 2005 he offered a different reason. “I know your sources are not idiots;’ he wrote in e-mail correspondence with the author, “but not one of those things you mentioned are [sic] accurate. Let’s start from the beginning.” Bavasi then wrote that while there was not a quota in effect, race was the factor in their decision to have Clemente play in Montreal rather than Brooklyn:

“[Dodgers owner] Walter O’ Malley had two partners who were concerned about the number of minorities we would be bringing to the Dodgers. … The concern had nothing to do with quotas, but the thought was too many minorities might be a problem with the white players. Not so, I said. Winning was the important thing. I agreed with the board that we should get a player’s opinion and I would be guided by the player’s opinion. The board called in Jackie Robinson. Hell, now I felt great. Jackie was told the problem, and, after thinking about it awhile, he asked me who would be sent out if Clemente took one of the spots. I said George Shuba. Jackie agreed that Shuba would be the one to go. Then he said Shuba was not among the best players on the club, but he was the most popular. With that he shocked me by saying, and I quote: “If I were the GM [general manager], I would not bring Clemente to the club and send Shuba or any other white player down. If I did this, I would be setting our program back five years.”10

Clemente in Montreal

So Clemente was headed for Montreal to play for manager Max Macon. According to statements attributed to Clemente in a 1966 Sports Illustrated article by Myron Cope, and later picked up by the biographers, the treatment he faced went beyond an attempt to hide him: “The idea was to make me look bad. If I struck out, I stayed in there; if I played well, I was benched.”11

Musick, in Who Was Roberto?, added, “A free swinger, Clemente suffered through stretches when he was not making contact with the ball. Fighting those slumps, he was showcased to disadvantage and stayed in the lineup days at a time.”12

However, box scores from The Sporting News reveal that Macon started Clemente in five straight games early in the season, a strange strategy if a team was trying to hide a player. Clemente had one hit in the first of those games, started again, had three hits, and started the next three games, coming out of the starting lineup only after going hitless in those final three games. This would seem to belie the claims that the organization was trying to make him look bad by rewarding a good performance with a benching and vice versa.

After those five starts Clemente played sparing ly over the next few months. Clemente may have, in part, been a victim of a crowded outfield situation in Montreal, which included Jack Cassini, Dick Whitman, and Don Thompson as well as Sandy Amoros, who was sent down from Brooklyn in mid May and recalled by the Dodgers in mid-July, and Gino Cimoli, who was transferred to Montreal from the Dodgers’ other Triple-A farm team, the St. Paul Saints, in early May. (Clemente’s opportunities to play may not have been any greater had he been assigned to St. Paul rather than Montreal. With Bud Hutson, John Golich, Bert Hamric, Ed Moore, and Walt Moryn, the Saints, like the Royals, were also heavy on outfielders.)

When Clemente did play, he struggled with his hitting. In early July, his batting average was barely above .200. Part of that may be attributed to his infrequent playing time; it’s hard for a batter to get in a groove and hit well when he doesn’t play regularly. On the other hand, it’s hard for a player to get regular playing time if he’s not hitting well.

Macon said the reason he didn’t use him much at that time was that he “swung wildly,” especially at pitches that were outside of the strike zone. “If you had been in Montreal that year, you wouldn’t have believed how ridiculous some pitchers made him look,” Macon said of Clemente.13

Macon was known around the league for platooning his hitters,14 and that is what happened with Clemente over the latter part of the season. In the first game of a doubleheader against Havana on July 25, Clemente entered the game in the ninth inning, came to the plate in the bottom of the 10th, and hit a game-ending home run.

He started the second game of the doubleheader, against lefthander Clarence “Hooks” Iotts; for the rest of the regular season and through the playoffs, the right-handed-hitting Clemente started every game in which the opposing starter was left-handed and did not start any games against right-handed starters. After July 25, Clemente’s usage was determined by the status of the opposing starting pitcher.

Other claims made to support the notion of Clemente being hidden:

- Clemente hit a long home run in the first week of the season and was benched in the next game.15 (Clemente did not homer until July 25, and he started the next game. His only other home run came on September 5, and, like his earlier homer, was a game-ending shot. Clemente did not start the next game as a right hander, Bob Trice, was the starting pitcher for Ottawa.)

- Clemente was benched after a game in which he had three triples.16 (Clemente did not have three triples in any game in 1954.)

- Clemente was often used only in the second game of a doubleheader, after the scouts had left. 17 (No such pattern of usage is indicated.)

The errors noted above were made by Wagenheim, Musick, and Markusen in their biographies. Maraniss, who went through Montreal newspapers for the 1954 season, avoided many of the inaccurate supporting examples made by the others. However, Maraniss parroted the claim that Clemente was being set up to fail, writing, “It seemed that whenever he got a chance to play and played well, Macon benched him.”18 Maraniss also wrote, ”After the first four games, Clemente was leading the team in batting, going four for eight. Then he disappeared again.”19 However, Clemente’s disappearance after getting three hits in the team’s fifth (not fourth) game was not that abrupt; he started and went hitless in the next three games before going back to the bench.

Overall, Maraniss stuck to the standard story of Clemente being hidden and did not perform any real analysis of the claim. He also did not pick up on the pattern of usage that eventually developed, in which Clemente started regularly against left-handed pitching. As a result, Maraniss cites instances of Clemente not playing over the final seven weeks as evidence of attempts to hide him, rather than the fact that a right-handed pitcher was starting for the opposing team.

One claim made by biographers that is true regards Clemente being pulled for a pinch-hitter in the top of the first inning of a game. It occurred June 7 at Havana. The Royals had two runs in and the bases loaded with two out when Havana changed pitchers right-hander Raul Sanchez coming in for left-hander Hooks Iotts. Left-handed Dick Whitman then hit for Clemente. Although the story is presented as more evidence of how poorly Clemente was treated by Max Macon, it appears clear from the circumstances that it had more to do with Macon’s affinity for platooning and a desire to try and break the game open.

An essentially opposite situation occurred two months later as Toronto manager Luke Sewell, trying to counteract Macon’s platooning, employed a decoy starter. In the first game of an August 3 doubleheader, Sewell started right hander Arnie Landeck against the Royals and then relieved him with left hander Vic Lombardi in the second inning. As a result, Dick Whitman started for Montreal and was pinch-hit for by Clemente before Whitman could bat even once. Conveniently, this counterpoint to the June 7 story is never mentioned.

Also, the details of Clemente getting pulled in the first inning get botched by the biographers. Markusen says the incident happened against Richmond in the second week of the season.21 Musick also says it occurred in a game against Richmond. However, a few pages later, Musick contradicts himself and says the game was in Rochester (wrong in both cases), that it was the last game of the season (not true), and it was against Rochester’s Jackie Collum (strike three).23

The name of Jackie Collum comes up again in an unrelated story by Wagenheim, who wrote that Clemente had two doubles and a triple off Collum and then was pulled for a pinch-hitter his next time up.24 Nothing like this happened — regardless of the pitcher.

And one has to wonder about references to Collum by two different biographers. Collum did not even pitch for Rochester, or in the International League at all in 1954.

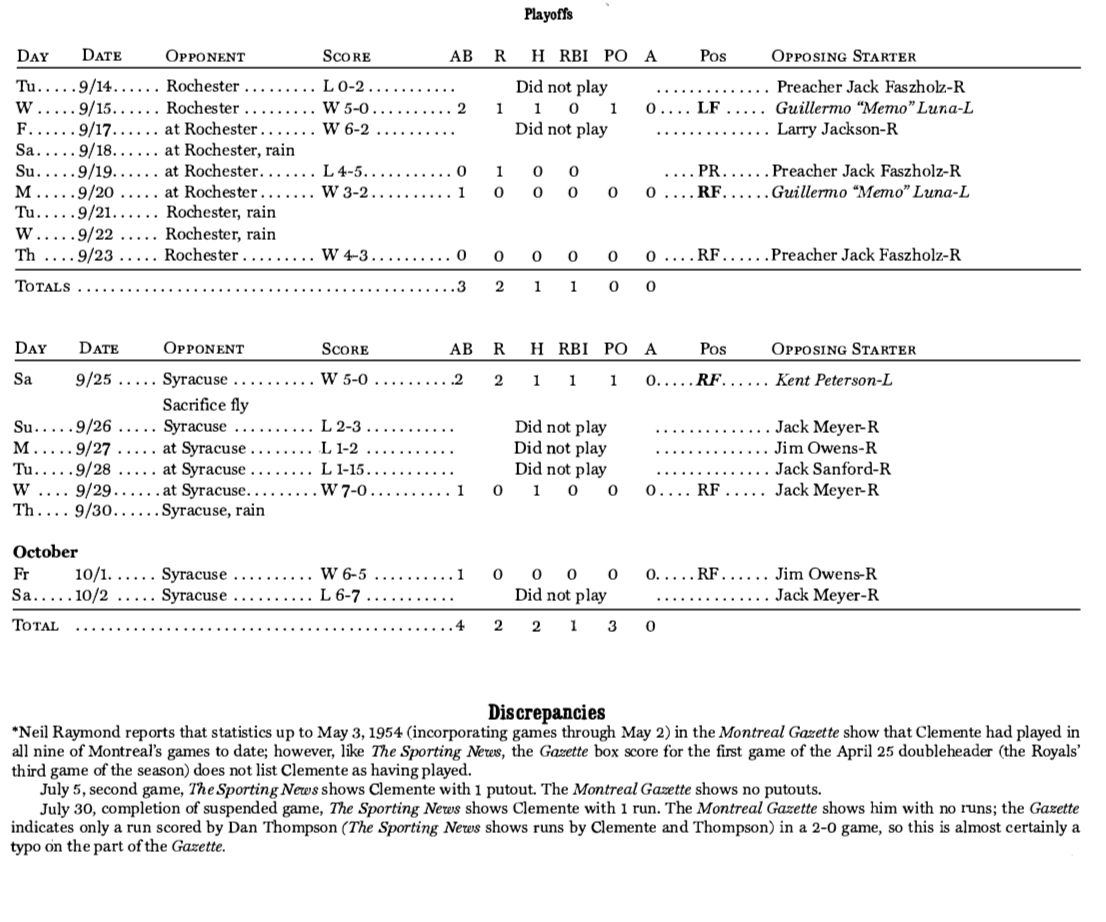

SABR member and Montreal Royals historian Neil Raymond cross-checked the summary compiled by the author from The Sporting News box scores with game accounts and box scores from Montreal news papers. (See Clemente’s game-by-game compilation at the end of the article.) “What becomes apparent going through the Montreal papers daily (La Presse, The Gazette, The Star) is that this team was not perceived as a player-development exercise;’ maintained Raymond. “They were expected to win. Translation: Sandy Amoros’s at-bats were deemed a lot more valuable than learning what Clemente could do, building his confidence, or training him by exposing him to opportunities to fail by being overmatched.

“I feel safe in saying that Clemente made very little impression on those who wrote about him during the 1954 campaign. These were iconoclastic writers. Their copy was eagerly sought-after breakfast or dinner fodder. If Clemente was being ‘hidden’ to the detriment of the team’s ability to perform, they would have peeped up. Not once in my newspaper research is there an allusion to this possibility, or a subtle wink at the canniness of the ‘brain trust.’ As difficult as it may be to accept to those who, like me, marveled at Clemente’s multifarious skills and dynamism throughout the 1960s (the bad-ball hitting, the cannon-like arm, the heady base running, etc.), it’s abundantly clear that he was almost an invisible man in Montreal in 1954.”25

A More Plausible Argument?

It’s possible that the strongest argument for a theory of hiding could revolve around the timing of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ discovery of Clemente and when Clemente began starting regularly against left handed pitching.

The accounts surrounding the discovery are consistent in some ways, albeit consistently inaccurate on some details: Clyde Sukeforth, then a Pirates coach, was dispatched on a scouting mission by Branch Rickey, then the Pirates executive vice president general manager, to check out Montreal pitcher Joe Black. All accounts say this occurred during a Royals series against Richmond in July. Almost every story says this series was in Richmond, with some of the accounts specifically mentioning Richmond’s Parker Field, although the only series between the two teams that month was in Montreal.

Sukeforth said Black did not pitch that series (not true, he did) and that Clemente’s only appearance was as a pinch-hitter (also not true; his only appearance in the series was as a pinch-runner). Even though Clemente barely appeared in the series, Sukeforth said he noticed, and was impressed by, Clemente while watching him bat and throw in pregame practice. On the basis of Sukeforth’s report, Rickey sent scout Howie Haak for a follow-up visit.

The accounts vary to a much greater degree as to when the Pirates informed the Dodgers and/or Royals that they had discovered Clemente and planned on drafting him. Some reports contend that Sukeforth immediately told Macon of the Pirates’ interest in Clemente.26

The key is when the Dodgers organization found out that the Pirates were planning to draft Clemente. If Clemente was first discovered in the Richmond series in July (meaning that the essence of the story of Sukeforth’s scouting trip is correct even if the specific details are not), and if Sukeforth immediately informed Macon, it raises an interesting possibility. The Richmond series was immediately before the Havana series in which Clemente began starting regularly against left-handers.

If the Royals began playing Clemente more after being informed of the Pirates’ interest, then perhaps it could be argued that the Royals had been hiding Clemente up to that point; however, informed that their gambit had failed, they then decided to play Clemente more.

Even if all these ifs line up, the argument is still a stretch and nothing more than conjecture; however, it is still the most plausible one.

Interestingly, however, this is not the argument advanced by the biographers or anyone else claim ing that Clemente was being hidden. In fact, most go in the other direction, saying that the Royals used Clemente even less after being informed of Pittsburgh’s interest. Wagenheim and Markusen even make the outrageous and totally incorrect claim that Clemente did not play in any of the Royals’ final 25 games.27 Although Musick does not make the claim of Clemente not playing in the last 25 games, he writes that Macon restricted Clemente’s playing time even more after Sukeforth’s scouting trip and alleged revelation to Macon.28

Treatment of Max Macon

Maruksen at least provided some balance with quotes from Macon in which the manager denied being under orders to hide Clemente.29 Musick also provided some of Macon’s denials as well as Macon’s contention that pitchers were making Clemente look ridiculous. However, Musick offered these explanations on Macon’s part in a patronizing manner as he wrote, “Macon pleads innocence for his former employer twenty years after the fact, but his pleas bring bemused grins to the faces of his contemporaries. And he is part of a baseball establishment that is superprotective of its leaders. There are no skeletons in baseball’s closet: They are quickly ground to dust and scattered to the four winds, lest men of stature be embarrassed.” Musick also refers to Macon’s “southern drawl” becoming “increasingly less reassuring to the player’s Puerto Rican ears.”30

Drafted by Pittsburgh

By the end of the 1954 season, it had become clear to Bavasi and the rest of the Brooklyn brass that other teams were interested in Clemente. However, Bavasi said he still wasn’t ready to give up. The Pirates, by having the worst record in the majors in 1954, had the first pick in the November draft.

If Bavasi could get the Pirates to draft a different player off the Montreal Royals roster, Clemente would remain with the Dodgers organization. (Each team could lose only one player, so if a different Montreal player was taken, then no other team could draft Clemente or any other Royals player.)

Bavasi said he went to Branch Rickey, who had run the Brooklyn Dodgers before going to Pittsburgh. Bavasi had declined Rickey’s offer at that time to follow him to the Pirates, but, according to Bavasi, Rickey then told him, “Should I [Bavasi] need help at anytime, all I had to do was pick up the phone.”

Bavasi said he used this offer of help in 1954 to get Rickey to agree to draft a different player, pitcher John Rutherford, off the Royals roster. However, Bavasi was dismayed to learn two days later that the deal was off and that the Pirates were going to draft Clemente. “It seemed that Walter O’Malley and Mr. Rickey got in another argument, and it seems Walter called Mr. Rickey every name in the book,” Bavasi explained. “Thus, we lost Roberto.”31

Summary

Some stories and claims may be difficult to fully verify or refute, and it’s possible that the contention that Clemente was being hidden and/or mistreated in Montreal is one of them. While this analysis may not provide a definitive answer one way or another, it is telling that the examples used to support the hiding claim are so consistently incorrect.

In a rather supercilious manner, Phil Musick wrote, “Whether or not the Dodgers consciously tried to hide Clemente from the prying eyes of scouts from other major league clubs is questionable-barely. The evidence insists that the Dodgers ordered him into virtual seclusion in Montreal; Macon insists other wise. The evidence does not support his claim.”32

In reality, the claims not supported by the evidence are those made by Musick and the other biographers.

A SABR member since 1979, STEW THORNLEY received the SABR-Macmillan Baseball Research Award in 1988 and the USA Today Baseball Weekly Award for the best research presentation at the 1998 SABR convention in San Mateo, California.

Notes

1. Barbara Schmidt’s web site on Mark Twain (www.twainquotes.com/ Lies.html) says this quote has never been verified as originating with Twain and that a related quote may have originated with British preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon, who attributed it to a proverb that he once used in a sermon.

2. The Sporting News, March 3, 1954, 26.

3. The bonus rule in effect at that time is chronicled in Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953-1957 by Brent Kelley, Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1997. The rule is also discussed in a Baseball America article (“Despite Baseball’s Best Efforts, Bonuses Just Keep Growing” by Allan Simpson, June 20-July 3, 2005, 10-12). This article says, “Players with less than 90 days of pro experience were designated as bonus players if they signed multi-year contracts or were promised more than $4,000 from a major league team. Bonus players kept their tag for two years. They had to be placed on major league rosters immediately and could not be optioned to the minors unless they cleared waivers.”

4. “Roberto Clemente’s Problem” by Howard Cohn, Sport, May 1962, 56.

5. Roberto Clemente: Batting King by Arnold Hano, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1973 (update of 1968 edition); Clemente! by Kal Wagenheim, New York: Praeger, 1973; Who Was Roberto? A Biography of Roberto Clemente by Phil Musick, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974; Roberto Clemente: The Great One by Bruce Markusen, Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 1998; Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero by David Maraniss, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

6. Musick, 80, 87; Markusen, 26.

7. “Dodgers Signed Clemente Just to Balk Giants” by Les Biederman, The Sporting News, May 25, 1955, 11.

8. Wagenheim, p. 35; Markusen, 33-34.

9. The claim that the Dodgers would not start five blacks in the same game was made by Wagenheim on page 35 of Clemente! Box scores of Brooklyn Dodgers games in 1954 from The Sporting News indicate four instances in which Jim Gilliam, Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, Sandy Amoros, and Roy Campanella were all in the starting lineup: July 17, August 24, September 6 (second game), and September 15. (The Dodgers had one other black player, pitcher Joe Black, briefly on their roster in 1954, but Black did not start any of the five games in which he pitched.)

10. E-mail correspondence with Buzzie Bavasi, June 3, 2005.

11. A quote from Clemente that contains these claims is in ”Aches and Pains and Three Batting Titles” by Myron Cope, Sports Illustrated, March 7, 1966, 34. One or both of the sentences in the Clemente quote listed in this article are from Wagenheim, 40; Musick, 81; and Markusen, 26.

12. Musick, 81.

13. Musick, 89.

14. The Sporting News, August 18, 1954, 34.

15. Musick, 80-81; Markusen, 18-19.

16. This claim is made in the quote attributed to Clemente in Cope’s 1966 Sports Illustrated article and also picked up by Hano, 27; Wagenheim, 40; Musick, 81; Markusen, 19.

17. Markusen, 27.

18. Maraniss, 46.

19. Maraniss, 43.

20. On page 51, Maraniss tells of a visit by Dodgers front-office personnel but that “it was back to the bench” upon their departure. He also does the same thing on pages 51-53 with stories of the trips by Pittsburgh Pirates scouts to see Clemente, claiming that Macon refused to play Clemente when scout Howie Haak visited. In reality, from the time that Clemente began platooning regularly, there were never more than two consecutive games in which he did not play, and, of course, these were games in which the opposing starting pitcher was right-handed.

21. Markusen, 19.

22. Musick, 81.

23. Musick, 87.

24. Wagenheim, 42.

25. E-mail correspondence with Neil Raymond, July 2005.

26. The discovery of Clemente is described in Cope’s 1966 Sports Illustrated article, 34; also by Hano, 29-30; Wagenheim, 41-42; Musick, 84- 87; and Markusen, 22-24; Maraniss, 51-53, and it is also covered in Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh: Baseball’s Trailblazing General Manager for the Pirates,1950-1955 by Andrew O’Toole, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000, 140-143.

27. Wagenheim, 42; Markusen, 26-27.

28. Musick, 84, 86.

29. Markusen, 26-27.

30. Musick, 86, 88-89.

31. E-mail correspondence with Buzzie Bavasi, June 3, 2005.

32. Musick, 80.

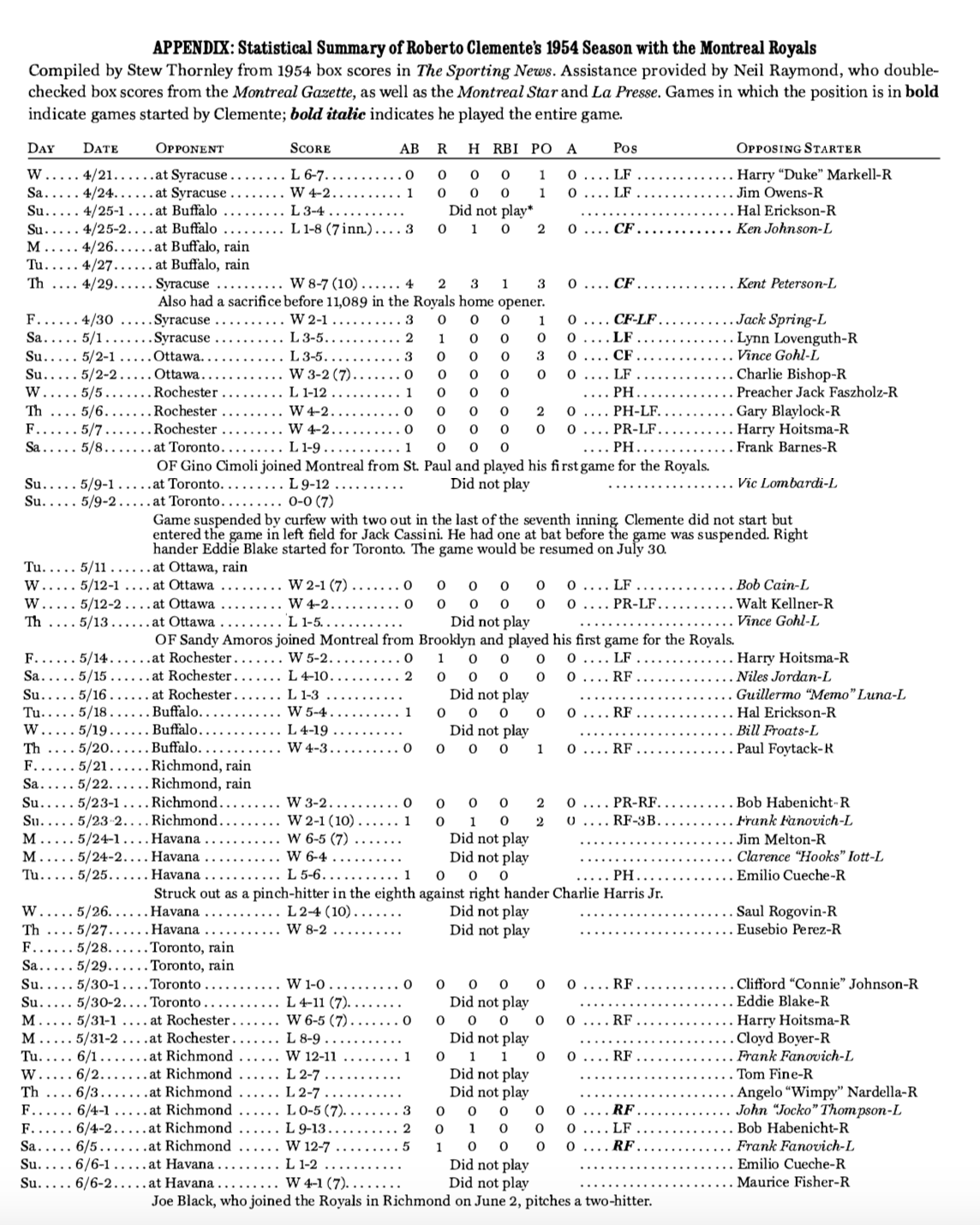

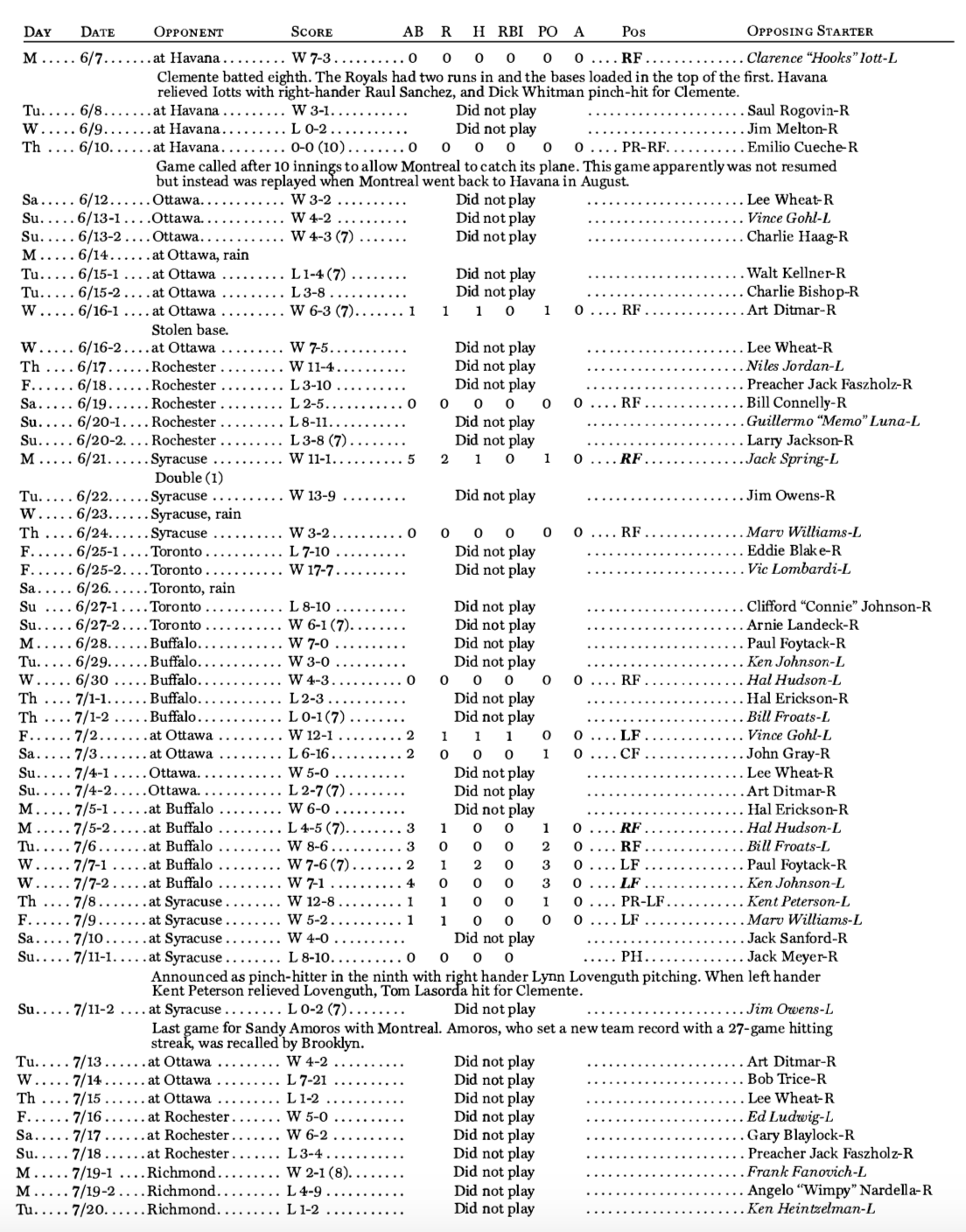

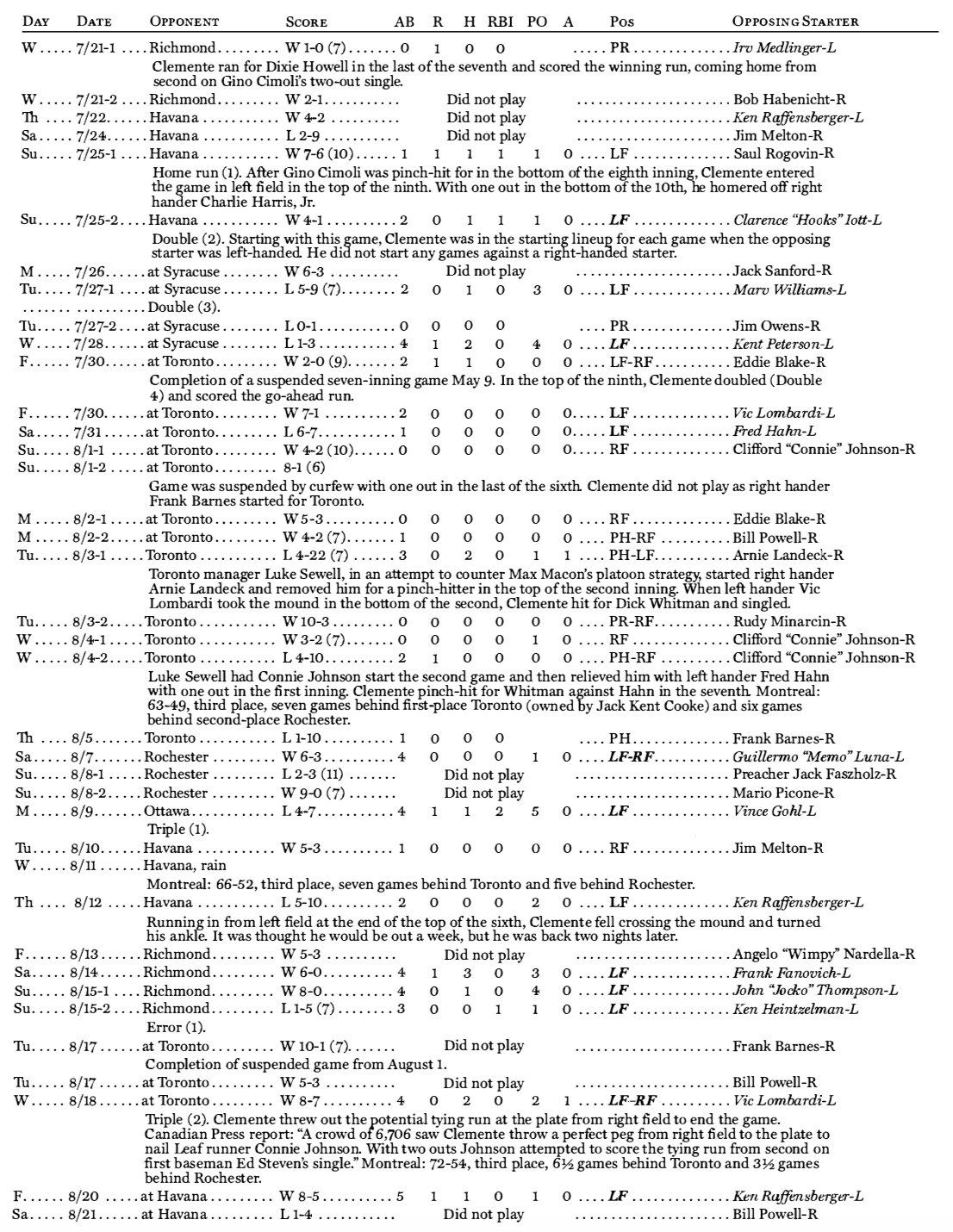

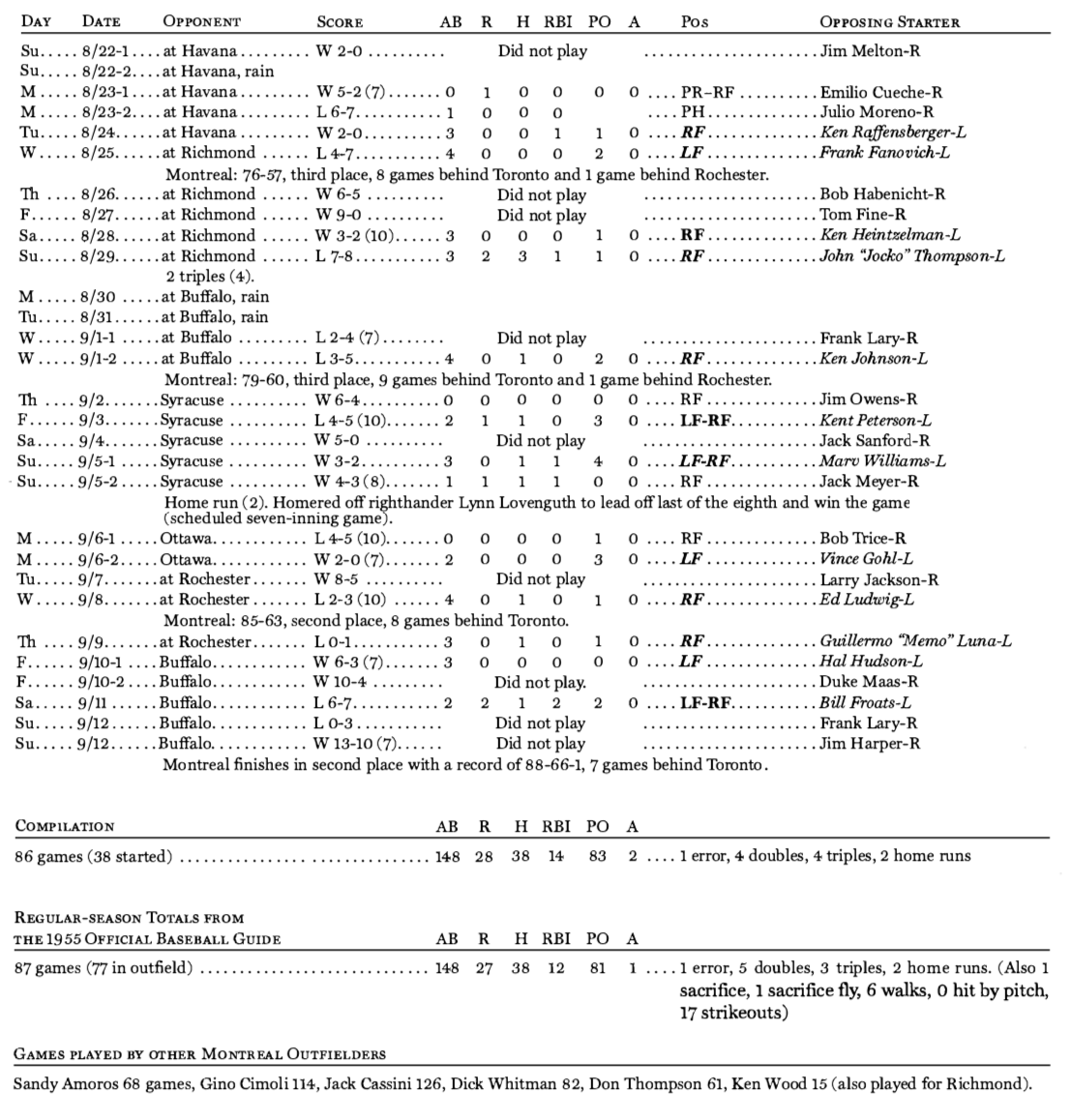

APPENDIX: Statistical Summary of Roberto Clemente’s 1954 Season with the Montreal Royals

(Click images to enlarge)