Cliff Kachline: Baseball Man and SABR Pioneer

This article was written by Bob Obojski

This article was published in 2001 Baseball Research Journal

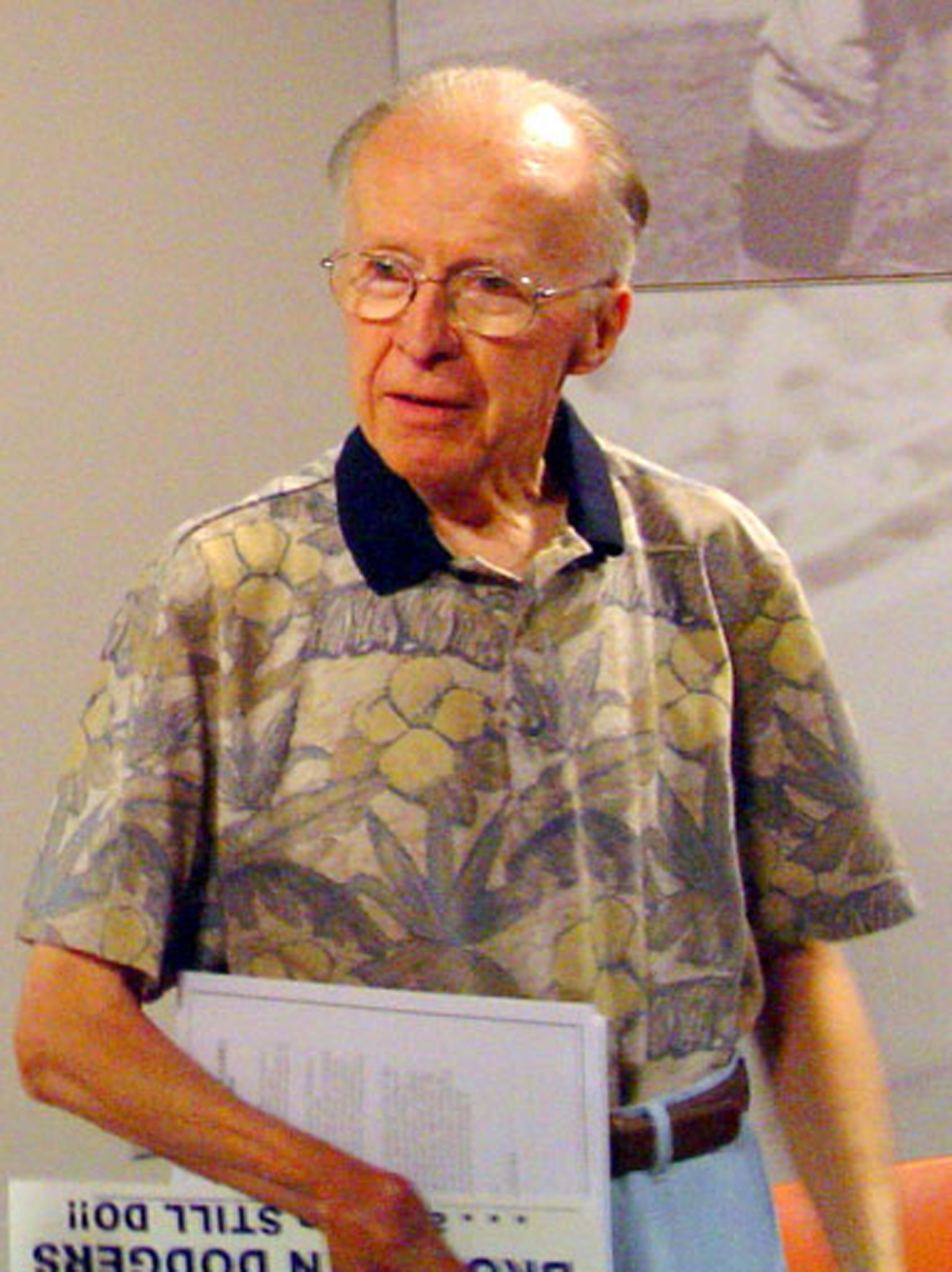

Cliff Kachline has been deeply involved in sports: writing, sports memorabilia, and almost everything else connected with sports — especially baseball — for more than a half century, and through it all he’s maintained his boundless energy, youthful high spirits, and keen sense of humor.

Cliff Kachline has been deeply involved in sports: writing, sports memorabilia, and almost everything else connected with sports — especially baseball — for more than a half century, and through it all he’s maintained his boundless energy, youthful high spirits, and keen sense of humor.

In The Politics of Glory: How the Baseball Hall of Fame Really Works, Bill James devoted an entire chapter to Kachline’s near fourteen-year tenure as the Hall of Fame’s historian, from 1969 to late 1982.

Kachline, a native of Quakerstown, Pennsylvania (a town of about 7,000, thirty-five miles north of Philadelphia), began his career in 1940 as a $7-a week printer’s apprentice and writer with his hometown weekly. Shortly after taking the job he almost lost his right hand in a printing press accident. Despite winding up with a stiff, slightly-crooked right wrist, he quickly learned to type rapidly and accurately. The following summer he became a full-time correspondent for a nearby daily, the Bethlehem Globe-Times. In the fall of 1942, he was named sports editor of The North Penn Reporter, a daily in Lansdale.

Early in 1940, The Sporting News carried an advertisement promoting the first edition of its new Baseball Register. The ad showed the year-by-year stats of two prominent players as they were to appear in the Register. Kachline noticed three mistakes in the record of one player — Frank McCormick, the 1939 National League MVP — and dashed off a letter to publisher, J. G. Taylor Spink, in hopes that the errors could be corrected before publication.

Within a matter of days, Spink wrote back to ask if Cliff would be interested in proofreading the entire Register. He jumped at the opportunity and soon received a huge package containing galley proofs of the major and minor league career records of 400 players. The book was due to go to press, so he had only a week to check the material.

The following winter, by then recovering from his hand injury, he was again asked by Spink to check the records. Now armed with a copy of Who’s Who in Baseball and other sources, he spent four weeks at the family’s kitchen table with the help of his mother, comparing and reviewing the latest proofs and correcting many errors and typos. Early in April, 1943, Spink invited the twenty-one-year-old Kachline to come to St. Louis to work full-time on the publication’s staff. In those days, The Sporting News covered major and minor league baseball only, and nearly all its reference books were baseball oriented.

For nearly a quarter century, Kachline wrote countless features and news articles, credited and uncredited, for TSN, and by the early 1950s his byline began appearing on front page news stories as well as on features on the inside pages. For much of that time, he also edited all of The Sporting News standard reference books, including the annual Official Baseball Guide, the Baseball Dope Book, Baseball Register, Knotty Problems and others. These annuals are now collector’s items, and it doesn’t take the baseball hobbyist long to find out that vintage editions in good shape sell at many, many times their cover price.

The Official Baseball Guide represented a prime off, season assignment for him starting in 1948. Spalding and Reach had published guides from the early 1880s through 1939. In 1940 and 1941 they joined forces to produce a single annual. In 1942 The Sporting News took over the publication of the annual and has continued to do so to this day. For the first few years, the TSN guides rated a bit below the caliber of the old Reach and Spalding annuals, but once Kachline got fully in harness in St. Louis in the late 1940s, the contents were much improved.

TSN guides of that period are now considered classics. The 1954 volume, for example, contains 576 pages, lots of photographs, the official averages of the majors and the thirty-eight minor leagues, and the official playing and scoring rules. The few full-page ads are primarily from sporting goods companies. The price of the publication was $1, but as Kachline noted: “I don’t think Taylor Spink was too concerned about making any real profit from the Guides.”

In its earliest issues, TSN cut down on the space given to obituaries of baseball figures, but under Kachline, the obit section of the guide contained accounts of anyone who played even a single game in the majors. Each year starting in 1947 he collected dozens of interesting and noteworthy filler items to round out the pages, wrote special features, and created a detailed account of the history of the preceding major league season, an account that dominated the forepart of the TSN guides.

Kachline was also a stickler for getting his stats straight. For example, when Bob Feller, Cleveland’s fireballing righthander, struck out 348 batters in 1946, his accomplishment was thought to be the all-time major league strikeout record for one season, surpassing the 343 K’s chalked up by lefthander Rube Waddell of the Philadelphia Athletics in 1904. Kachline, however, researched Waddell’s 1904 season boxscore by boxscore, and proved that Waddell had actually fanned 349, a figure that was eventually accepted by the baseball establishment. (Waddell’s record was subsequently broken by Sandy Koufax and Nolan Ryan, though he still holds the single-season American League record for a lefthander.)

“You’d be surprised at the number of mistakes that official scorers make when they turn in their scoresheets,” Kachline emphasized. “Lots of times they’re under deadline pressure to complete those scoresheets, and they don’t bother to check out all the key stats.”

In 1983, The Sporting News received game-by-game breakdowns of Nap Lajoie’s 1901 batting record, which two researchers from different parts of the country had compiled from boxscores. For years Lajoie had been listed with 220 hits and a .405 average for that season instead of the .422 with which he was originally credited. One of the researchers came up with 229 hits, the other with 232. Spink turned the matter over to Kachline. Because the official American League statistical compilations no longer existed, this presented a problem similar to that involving the Waddell strikeout total.

Since the league’s president, Ban Johnson, and statistician were both headquartered in Chicago, Cliff figured the final official 1901 averages would first have been published in Chicago newspapers. He arranged to obtain photocopies; they credited Lajoie with 229 hits and a .422 average. Kachline, with his knowledge of printing, realized that type-set proofs of the averages could easily have had a smudged “9” that was interpreted as a zero, thus explaining the erroneous 220 hits instead of 229.

More recently Kachline was involved in the research of several other records which were in dispute, including Hack Wilson’s major league RBI record. In 1999 the Commissioner’s office formally endorsed the finding that Wilson had 191 RBIs — rather than 190 — for the Chicago Cubs in 1930.

The two standard references in recent years — The Baseball Encyclopedia and Total Baseball — have disagreed on the stats of numerous players. Kachline believes there should be one authority to rule on discrepancies-such as the Official Records Committee that functioned from 1975 through 1982 with the approval of the Commissioner’s office.

In the mid-1960s Kachline served a two-year term as president of the St. Louis chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. He was the first TSN staff member ever to hold that position. BBWAA officers are usually affiliated with metropolitan dailies based in and around major league cities. He remains an honorary BBWAA member.

On to the Hall of Fame

In May 1967, Kachline left The Sporting News after twenty-four years to become public relations director of the newly-formed United Soccer Association, then headquartered in New York City. The owners of several major league baseball clubs, including Roy Hofheinz, Gabe Paul, and John Allyn, as well as such sports entrepreneurs as Lamar Hunt and Jack Kent Cooke, had teams in the league. Late that year, following a merger with a rival circuit, the league was renamed North American Soccer League. After two seasons, it folded, and Kachline found himself in the job market.

When Lee Allen, historian of the Baseball Hall of Fame, died in May 1969, Hall president Paul Kerr contacted former baseball Commissioner Ford Frick for his recommendation of someone to fill the position. Frick recommended Kachline, and he occupied the role of Hall of Fame historian for nearly fourteen years before being dismissed at the end of October 1982 in what Bill Madden, prominent New York Daily News baseball writer, termed “a surprise move that reeks of in-house politics.”

The Hall of Fame historian post wielded considerable influence through the whole baseball community. Because Kachline possessed a strong personality and an encyclopedic knowledge of the sport, he helped to make the position more significant than ever before.

One important and time-consuming chore involved responding to the hundreds upon hundreds of letters and phone calls from fans, visitors, writers, major league clubs, and even former players seeking information.

He developed a booklet that detailed the history of the Hall of Fame, and included historical and statistical information on each member. He also prepared the inscriptions for the bronze plaques of newly elected HOF inductees. When a major $3,000,000 expansion, renovation and updating of the institution was begun in the mid-1970s, he was given the assignment of coordinating efforts with the design firm and editing the captions of the new exhibits.

The contacts he had developed with many baseball officials during his years at The Sporting News proved of immense benefit to the Hall of Fame. During his first year there he realized that many major league teams were storing historically valuable material such as correspondence, contracts, financial records, and old publications, and that this material might eventually be disposed of. He wrote to all twenty-six clubs suggesting that the Hall would be interested in looking over such material and salvaging important items for the Hall of Fame archives.

Dick Wagner, Cincinnati’s assistant general manager, was the first to respond. The Reds were preparing to move from old Crosley Field to new Riverfront Stadium later in the season, and Wagner invited Kachline to come to Cincinnati to sift through the storage area under Crosley’s stands. After a quick look, he realized he had come across a veritable goldmine of baseball players, both major and minor league. The cards, dating back to 1902 and compiled under the aegis of club president Garry Herrmann, listed the clubs to which the player belonged each year.

Kachline visited many clubs during the next few years, before his involvement in the museum expansion forced him to change his focus. Among his other acquisitions were Yankees’ financial ledgers from the 1920s and 1930s, historic documents from the files of the Commissioner’s office, and the player card files that the National Association no longer needed when the minor league headquarters were moved from Columbus, Ohio, to Florida.

“With the materials we found on those scavenging expeditions and those donated by various clubs and the Commissioner’s office, the Hall of Fame Library grew into an enormous collection of valuable source material, such as team yearbooks, roster guides, World Series programs, World Series films, photographs, old scorecards, documents and similar items,” Kachline commented. “And almost all has been liberally used by researchers.”

Kachline quickly realized that the number of visitors to the Hall of Fame fell far short of what he felt it should be. Attendance during his first year there (1969) was reported as 191,000. With the approval of the Hall’s higher-ups, he worked with Tom Dawson, then director of radio and TV for the Commissioner’s office, to arrange for free promos for the Hall on Game of the Week telecasts, and he induced the individual clubs to run the spots, too. The museum’s attendance began rising steadily.

Noting that almost no major league club officials ever visited Cooperstown except when their team played in the annual Hall of Fame game, Kachline suggested in 1973 that an attempt be made to get the general managers to hold their annual fall meeting in the so-called “Home of Baseball.” At the time the village’s only hotel, which like the Hall of Fame was controlled by the Clark family, closed before the World Series ended, but he nevertheless was given the okay to pursue the idea.

Through his contacts with Frank Cashen, then with the Baltimore Orioles, a proposal to have the general managers meet in Cooperstown the following year was approved at the GMs’ October 1973 session in Scottsdale, Arizona. Unfortunately, when Kachline relayed word of the decision, Hall president Paul Kerr changed his mind about keeping the hotel open a few extra days to accommodate the group. As a result, Cooperstown did not host an official meeting of major league executives until the owners’ meeting there in the fall of 1999.

An indication of the respect which baseball officials had for Kachline was exhibited when he was asked to serve as editor of the Official World Series program. Prior to 1974, each World Series team produced its own program. With expansion and the divisional playoffs, there were occasions when eight or more clubs spent considerable time and money preparing a program, only to fail to reach the Series. To eliminate the wasted efforts, it was agreed that the Commissioner’s office would handle production of the Series programs. Kachline served as editor from 1974 through 1977 before the Commissioner’s office decided to handle the entire project in-house.

Another tribute to Kachline’s abilities and dedication came late in 1979. A dozen years after he had left The Sporting News, the publisher called to inquire if he would again write the lengthy Review of the Year that he had made an important feature of the Official Baseball Guide. Chicago writer Jerome Holtzman had handled this assignment during the intervening twelve years but had decided to discontinue doing so. Kachline’s accounts appeared in the Guides of 1980 through 1991 before he chose to relinquish the role.

Other significant innovations which Kachline was responsible for during his tenure with the Hall of Fame included the Baseball Today exhibit and having Museum attendants outfitted in distinctive red jackets. “The Museum had attendants available to assist visitors who might have questions, but it was almost impossible to distinguish them from visitors,” Kachline said. “On a scavenging trip to St. Louis, I spotted a long rack of red jackets. It turned out the ushers at Cardinal games wore them one season, but complained it was too hot for jackets. The Hall of Fame arranged to buy a dozen or so from the Cardinals.”

As for the Baseball Today exhibit, the Museum previously had essentially no display devoted to the current teams. The new exhibit featured the uniform, player, manager, and stadium photos, of each major league team and proved to be extremely popular, especially among younger visitors.

Shortly after Kachline’s departure from the Hall of Fame in 1982, he sent an open two-page letter addressed “To the Commissioner, league presidents, general managers, PR directors and other interested parties” detailing events that led up to his dismissal. The strongly-worded letter concluded with this statement: “If all of this has you puzzled, you can appreciate my bafflement. After 40 years of close association with baseball-dating from my start with The Sporting News in 1943-developments at the Baseball Hall of Fame have left me wondering whether the best interests of baseball are always being served.”

Since Kachline’s departure, the title “Hall of Fame historian” has also disappeared. Functions of that office are now spread out among several members of the Hall of Fame staff.

SABR

Early in 1983, Cliff accepted the newly-created position of executive director of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). He was one of sixteen baseball aficionados who gathered for the organization’s founding meeting in the Hall of Fame Library in August 1971. By the end of 1982, SABR membership had risen to 1,800 and the Board decided that a full-time paid administrator was required. In his three years as executive director before retiring, he saw membership climb to 6,200.

Prior to Kachline’s appointment, founder Bob Davids had written SABR’s bimonthly newsletter and edited the annual Baseball Research Journal as well as most other SABR publications. Once Cliff was named administrative head of the organization, Davids turned those writing and editing chores over to him. Many of the early SABR publications are now regarded as baseball classics and rate as prime collector’s items among those who specialize in baseball publications.

Cliff and his wife Evelyn, who handled the SABR financial records and membership rolls from 1975 through 1985, own a home on a two-acre property on the outskirts of Cooperstown. Among their prized possessions are four reddish-orange seats from old Sportsman’s Park, the one-time home of the St. Louis Cardinals and St. Louis Browns. The Kachlines have two married daughters: Jeri, who lives in suburban Atlanta, Georgia, and has two boys, and Joyce, who resides in central Illinois and has two girls.