Clyde Sukeforth: The Dodgers’ Yankee and Branch Rickey’s Maine Man

This article was written by Karl Lindholm

This article was published in Spring 2014 Baseball Research Journal

“But then Clyde Sukeforth is an unusual fellow. He is a medium-sized, lithe-limbed chap with the expression of eternal youth in his sharp but regular features. He hails from up in the state of Maine and leads a rugged outdoor life the year round.” — Tommy Holmes1

Clyde Sukeforth shrugged off his importance to the Jackie Robinson story, but Robinson didn’t. (BARNEY STEIN / COURTESY OF KARL LINDHOLM)

Clyde Sukeforth was the consummate Yankee, though he was never associated with the New York Yankees baseball club, and for 20 of the 48 years he drew a paycheck in baseball, he was a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Yankees’ arch-rivals. Sukeforth was a Yankee from Maine.

As Branch Rickey’s collaborator and confidant, Sukeforth is well-known for his role in the Jackie Robinson integration saga. He was the scout who met with Robinson in Chicago in August of 1945 and accompanied him to Brooklyn for the historic meeting in which Rickey informed Robinson he wanted a “man with guts enough not to fight back.”2

Sukeforth was in the room that day, and on the bench as manager of the Dodgers for Robinson’s first game as a major leaguer on April 15, 1947. “Sukey,” as he was known, shrugged off the importance of his contribution: “I was just the right person at the right place at the right time.”3

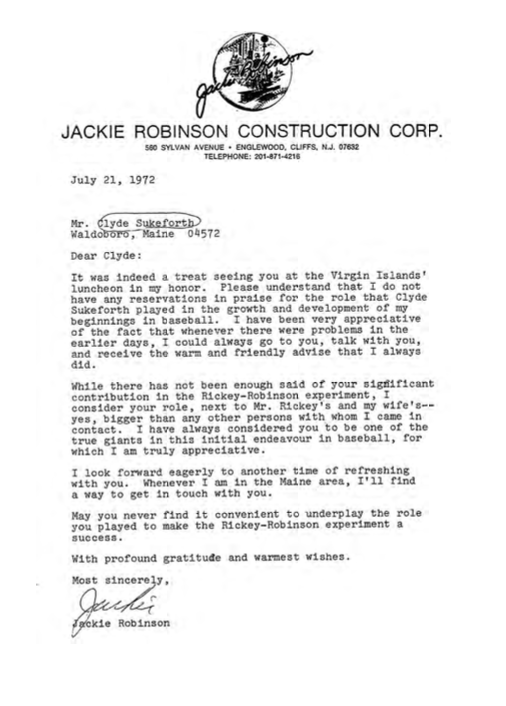

Jackie Robinson, however, felt otherwise. Near the end of his life (he died in 1972 at age 52), he expressed his appreciation in a letter to Sukeforth at his home in Waldoboro, Maine:

While there has not been enough said of your significant contribution in the Rickey-Robinson experiment, I consider your role, next to Mr. Rickey’s and my wife’s—yes, bigger than any other person with whom I came in contact. I have always considered you to be one of the true giants in this initial endeavour in baseball, for which I am truly appreciative.

May you never find it convenient to underplay the role you played to make the Rickey-Robinson experiment a success.4

Yet that’s exactly what Sukey did. He always downplayed his importance in baseball’s integration drama: “I get a lot of credit I don’t deserve. I treated Robinson just like any other human being,” he said near the end of his long life. “See, coming from Maine, I never thought about color. I don’t feel I did anything special. I was just there.5

“Many people have the impression that I was the first man to scout Jackie Robinson, but everybody in America knew what talent he had. Nobody but Branch Rickey deserves any credit. They have given me too much credit.”6

One could expect nothing else from Sukey. He was a Mainer, after all.

TEAM PLAYER

People from Maine are “Yankees,” broadly speaking, and a composite of all those character traits New Englanders associate with the term: Yankee industry, reticence, practicality, resourcefulness, frugality, loyalty, independence, humility. Yankees abhor pretension and avoid ostentation. Their discourse is ironic and understated: they are straight talkers with a wry sense of humor. Austerity and simplicity are virtues. “Times change,” they say, “but I don’t.”

Clyde Sukeforth symbolized competence and dependability in the workplace. In his biography of Branch Rickey, Lee Lowenfish refers to the “taciturn native of Maine” as “one of the most trusted members of Rickey’s inner circle.”7 As such, he was not the star, the boss, one of the principals—it was Rickey’s and Robinson’s show.

He was a team player, happier in the shadows than the limelight. He is baseball’s most famous factotum. Sukeforth was crucial but not central—and that’s just the way he liked it. “I was perfectly happy and satisfied to be a coach,” he told a Pittsburgh reporter in 1957, “to stand in the wings and help put the play on the stage.”8

Befitting his nature, he was a catcher—a 5’10” 155-pound catcher. A receiver, not a deliverer. Pitchers may be vain, flighty; catchers are humble, solid. They see the whole field, play the entire game. There are no relief catchers. They go the distance. Many great catchers historically came from New England: Bill Carrigan, Connie Mack, Gabby Hartnett, Mickey Cochrane, Birdie Tebbetts, Jim Hegan, Carlton Fisk.

Clyde Sukeforth was born in Washington, Maine in 1901. He died in Waldoboro, 17 miles from his birthplace, nearly a century later in 2000. Sukey is an ideal representative of his region. Mainers are used to rugged times, hardship, bad weather, tough choices. They live a hardscrabble life, or at least they did when he was growing up there and adopting the values of his place.

He was the mythical young man from the provinces who went to the city and participated in an epic drama, and then, after an extraordinary career full of high adventure, repaired to his Ithaka — Waldoboro — to live out his long life, a sage in the tranquility of old age in familiar and reassuring surroundings.

More than anything, Sukey lived and loved the Yankee life and lifestyle. His daughter Helen Zimmerman, of Dallas, Texas, said of him: “He was a true Mainer…. He loved the outdoors, even in the winter, especially in the winter. He liked to hunt and fish, and always had dogs. He always found something to do in the winter. He would never have been happy in Florida or Texas.”9

Each year, after playing ball, or serving as a coach, scout, or manager during the warm 6-8 months of the baseball season, Sukeforth returned to Waldoboro for the offseason. For many years, he came back to his 100 acre farm on Blueberry Hill where he grew Christmas trees and blueberries. Then in the last 30 years of his life he moved to a more manageable cottage on a dirt road right on the water, on the Medomak Bay, a few miles below Waldoboro village.

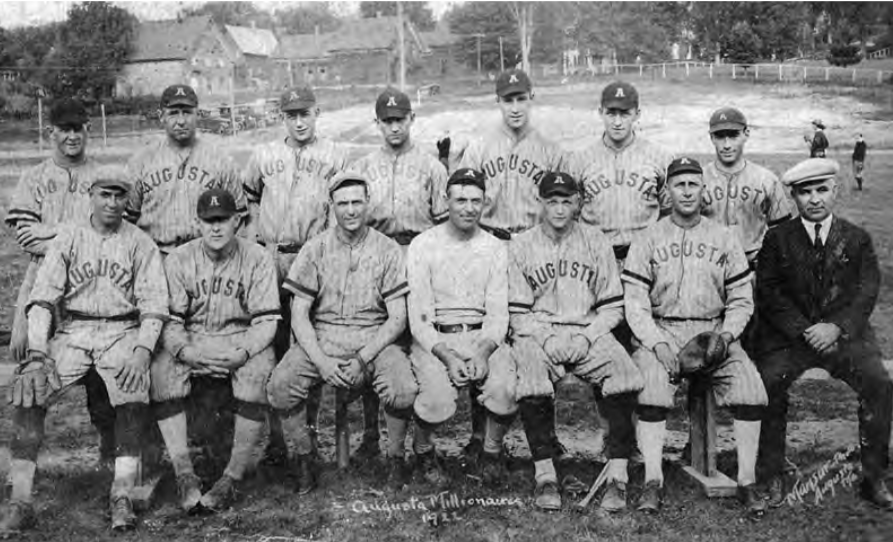

1922 Augusta Millionaires. Clyde Sukeforth is third from the left in the back row. Four other players on this team played in the big leagues. (MAINE BASEBALL HALL OF FAME)

NOTHING ELSE TO DO

Baseball was everything and everywhere when Sukey was a boy in coastal Maine at the turn of the last century. His dad was a farmer and a carpenter who shoveled snow in the winter for money. He also was a pitcher in his youth and his son early on showed an affinity for the game, playing every day the weather allowed. “Baseball was different then,” Sukeforth explained. “Every kid had a ball and glove, and threw the ball. You’d throw the ball seven days a week.”10

“There was nothing else to do. I mean, there were two things you could do; you could take your ball and glove and play catch with the neighbor’s kids, or you could dig a can of worms and go fishing on the trout brook. That was it!”11

They just played the game, outdoors, live. “We didn’t have a radio until 1930, and no TV until the early ’50s,” Sukey said. “The only way we got news was from the Boston Post, which came by stagecoach along about sunset every day. You’d have to get the Post to find out what the Red Sox did yesterday.”12

Clyde did get a chance to see two World Series games when he was 16. He went to Boston with his uncle for the wartime 1918 Series in which Babe Ruth shone as a pitcher for the Red Sox. “We walked right up to the ticket window and got tickets the day of the game. There were even empty seats,” Sukey recalled.13

He attended a one-room/one-teacher school house in Washington with his older sister, until he enrolled in Coburn Classical Institute in Waterville for his last two years of high school. “Then I stayed out of school for one year and worked for the United Lumber Company from one June to the next,” Sukey told a writer in 2000. “I’ve only done two things in my life: baseball and chopping wood.”14

“Right after World War I, industry was real good and all the manufacturing plants sponsored ball teams,” Sukey said in 1998. “I had always dreamed of playing professional ball, so in 1921 I made the Great Northern Paper Company ball club. We used to play in Bangor, Brewer, Bar Harbor, all around. They recruited all the better college players around, and paid more than the good ballplayers were getting in the minor leagues.”15

Sukey played all over the field as a youngster, but eventually settled on catching. His explanation was typically practical: “I wasn’t very big, but a small fella had a chance in those days. In the first place, if you’re gonna have a game, somebody’s got to catch.”16

He played two summers for Great Northern and also played for the Augusta Millionaires, a fast semi-pro team. A Pittsburgh newspaper later described these early years thus: “Sukeforth was raised in the Maine woods and played semipro ball in Millinockett. Some Georgetown college boys who were spending the summer took the young man back to college with them and he was a student at Georgetown for two years. ‘I played ball there and I loved the school,’ said Sukeforth.”17

So off he went to study and play ball at Georgetown 1923–25 where he attracted the attention of major league scouts. After two years, he was faced with the decision to continue on to a four-year degree or to play pro ball. In truth, it wasn’t a real dilemma. “I wanted to play ball—that’s all I wanted to do.”18

MAJOR LEAGUER

The Reds gave him $1,500 to sign and $600 a month and sent him to play for Nashua in the New England League in the summer of 1926. He was called up by Cincinnati in late May and got his first major league at-bat. He batted only once—and struck out. Nonetheless, he always claimed, “The highlight of my career was the first day I put on a big-league uniform.”19

For the next two years, he was the Reds’ third-string catcher, stuck behind “Bubbles” Hargrave, who led the National League in batting average in 1926, and veteran Val Picinich. Sukey finally got his chance in 1929, with the aging Hargrave gone to manage in the minors and Picinich traded, and had a marvelous season: in 84 games, he batted .354, by 40 points the highest average on the Reds and higher than any other catcher in the majors (Mickey Cochrane hit .331 for the Tigers that year).

Sukeforth was far from the lumbering Ernie Lombardi-type of backstop. He put the ball in play, and ran like the wind. “I took a big, heavy bat, choked up on it. I never had any power, but I could run. I legged out a few.”20 He struck out only six times that summer in 237 at-bats. For the next two years he was the Reds’ regular catcher, batting .284 in ’30 and .254 in ’31 in 112 games.

Then, misfortune struck. Just after the ’31 season, he was bird-hunting in southern Ohio with friends when, as he described it, “The bird jumped up before one of our fellows expected it and he took a quick shot at it. He got the wrong bird.”21

He shot Sukeforth in the face at close range. Sukey was hospitalized for weeks. One of the pellets had gone right through his right eye, rendering him nearly blind in that eye. He lived the rest of his life with shotgun pellets lodged in his head and an ability to detect only shapes with his bad eye. He described with typical aplomb the impact of this event on his baseball career. “I wasn’t a world beater before then, and the accident didn’t help any.”22

He was traded that winter, 1932, to the Dodgers (for Lombardi and others) and played three more undistinguished years before his major league career was over at age 32 after the 1934 season.

SUKEFORTH, THE MANAGER

Sukey stayed in the game, however, playing in the minors until 1939. In 1936 he was asked to be player-manager of the Dodgers farm club in Class D ball in Leaksville, North Carolina, and then the next year in Clinton, Iowa, a step up to B ball. The following two years, 1938–39, he managed Elmira (NY) in the Single A Eastern League before taking over the Dodgers top farm team (AA) in Montreal for three years, beating out Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby for that managerial job.23 He led good teams in 1940 and 1941, as the Royals contended for the pennant, finishing second both times.

Fans in Canada liked their neighbor from Maine with his restrained Yankee style. These comments from Montreal newspapers, from the Sukeforth file in the research library at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, make the point:

Self-effacing humor comes easily to him. He can go into extra innings talking about baseball while keeping his ego on the bench.”24

The quiet youthful man was well-liked from the start. Unlike some other managers we have had, Sukeforth proved that he is as good a listener as a talker.”25

Sukey is a rugged battler himself—although you’d never think it to look at the quiet-mannered, parson-like figure who walks to the third base coaching line in a semi-apologetic fashion.26

In the winter of 1941, the Montreal Standard sent a reporter to Waldoboro to profile the skipper of their club in the offseason. The result was a remarkable essay titled “Sukey of Blueberry Hill.” Pictures showed the Mainer shoveling snow to stay in shape, and squatting with his hunting dog, Martha, and his friend and neighbor, Val Picinich, his former teammate and rival for the catcher’s job in Cincinnati.27 Their conversation, according to the reporter, “usually centers around a hunting or fishing jaunt. Together they trek deer, foxes, or bag a few partridges whenever they’re in season. Smelt fishing provides an occasional diversion.”28

That winter, Sukey was “busy clearing some of the wooded land on his 100 acres and piling enough firewood to last the winter,” the Standard sportswriter reported. “He rises at six every day and retires between nine and ten every night.”29

The Standard article also introduced readers to Sukey’s two and a half year-old daughter, Helen, who was being raised in the baseball season by her grandmother, Clyde’s mother-in-law. Clyde’s wife, Helen Miller Sukeforth, whom he married in 1931, had died 15 days after giving birth to their daughter.

(Letter from Jackie Robinson to Clyde Sukeforth, July 21, 1972, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Click image to enlarge.)

THE DODGER YEARS

In 1943, Sukey was promoted to the big club in Brooklyn, where he would stay as coach, scout, and all-round handyman to Dodgers President Branch Rickey until 1951. He even played. In 1945 the roster was depleted by the war. Still slender and fit at age 43, Sukeforth was pressed into duty behind the plate in 1945, playing 18 games and batting .294 (15 hits in 51 at-bats).

With his natural unobtrusiveness, Sukey was the perfect man to participate in Rickey’s elaborate clandestine stratagem to integrate baseball. “Mr. Rickey had been talking about establishing a Negro team in New York called the Brooklyn Brown Bombers, and we had been scouting the Negro leagues for more than a year,” Sukey explained later. “He told us he didn’t want this idea of his getting around, that nobody was supposed to know what we were doing…. We made ourselves as inconspicuous as possible.”30

Like most white players of his era, Clyde was keenly aware of the skills of his black counterparts in the Negro leagues: “When we visited Pittsburgh we played during the day and came back to watch the Negro League games at night. I have to say the best catcher I have ever seen play baseball was Josh Gibson of the Pittsburgh Crawfords.”31

It is fitting that Sukeforth was the manager that day in April 1947, when Robinson put on the immaculate Dodger white home uniform to play the Boston Braves at Ebbets Field, and made history. It was expected that Leo Durocher would have that honor, but he had been suspended a few days before for consorting with gamblers, so Sukey stepped into the breach. He managed that day, and the next game too, and won both times, ensuring that forever his managerial record in the Majors would be perfect.

He had no interest in managing the team on a permanent basis, though he was asked by Rickey to do so. He had managed in the minors and knew the job and its demands and was clear that he didn’t want the added responsibilities of the major league position. When asked by reporters about his managerial aspirations, or lack thereof, he often replied in jest: “I’ll do anything Mr. Rickey wants me to. But if someone else comes along and says, ‘Well, you did okay in Brooklyn, how about managing full time with some other club?’ I’d be apt to say, Gotta pick some blueberries, Bud, see you later.”32

Sukey’s recommendation for the Brooklyn manager’s job was 62-year-old Burt Shotton, an old baseball hand, then a scout for the Dodgers, whom Sukey knew well and trusted. Rickey concurred, and Shotton finished out that ’47 season. The Dodgers won the pennant and extended the Yankees to seven games in the World Series.

Shotton managed the Dodgers in 1948 as well (after Durocher was fired in mid-season) and in 1949 and 1950. New York sportswriters referred to him as KOBS, “Kindly Old Burt Shotton,” but, with Sukeforth’s capable assistance, he was just the steady hand that the Dodgers needed in Jackie Robinson’s tumultuous first years.33

Shotton was an old-fashioned skipper, managing in street clothes in the manner of Connie Mack, so Sukey had an important role on the field. “Mr. Shotton became the manager and I became the leg man for him. So I was Mr. Shotton’s legs and he had the brains. What a combination. He did a marvelous job leading us to a pennant that year.”34

Sukeforth’s departure from Brooklyn after the 1951 season was attended by controversy. Baseball fans will recognize immediately that 1951 was marked by “the shot heard ’round the world” and Sukey was right in the middle of that. He was in the bullpen coaching that day in October when the Giants and Dodgers squared off in a final playoff game to determine the winner of the National League flag. As Dodgers ace Don Newcombe tired, Sukey personally caught both Ralph Branca and Carl Erskine at different times as they warmed up, and had a clear sense of who was more ready.

When Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen called the pen and asked for Sukey’s recommendation, Sukey replied that he thought Branca was throwing better. Two pitches later, it was bedlam in the Polo Grounds, and after the game, Dressen unhesitatingly pointed the finger of blame at Sukeforth. Sukey never retaliated, even averred in the New York press that he and Dressen, his former teammate in their playing days in Cincinnati, were friends. However, early in 1952, Sukeforth resigned from the Dodgers and accepted a coaching position with Pittsburgh, where his patron Rickey had taken over, hoping to breathe life into a moribund Pirates club.

SUKEFORTH AND BOB FLYNN

Bob Flynn was a terrific baseball player in Maine, signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates after he graduated from Lewiston High School in 1951. He spent the fall that year in Deland, Florida, with other Pirate hopefuls, attending daily baseball seminars by “Mister Rickey,” and working to refine his game and impress Pirates brass.

A few months later, in the spring 1952 Flynn was off to spring training in San Bernardino (CA). His itinerary had him going by train from Pittsburgh with other Pirates rookies (including Bobby Del Greco and Tony Bartirome, who went on to major league careers) and Pirates coach Clyde Sukeforth, their de facto chaperone and sage.

From his office in the athletic facilities at Bates College in Lewiston, Flynn, now 79 and mostly retired from coaching baseball and skiing, warmed to the recollection of that four-day trip west with Sukeforth. “We had a great time, relaxing talking about baseball, and other things. We spent a lot of time in the club car and dining car. He had a great knowledge of baseball, but we talked about a lot of things.”35

That summer, 1952, Flynn was playing minor league ball in Waco, Texas, when Sukeforth came through looking at prospects for the organization. They went out to dinner one night, the two of them (“I think he took a special interest in me because I was from Maine”), then played golf the following day, an off day for the club. In a double-header the day after golf, Flynn got a bunch of hits, the result he thinks of Sukey’s visit and their conversations.

Flynn’s baseball career was interrupted by the military draft. He spent 1953 and 1954 in Korea, and then played three more years in the Pirates farm system, before determining that the “real world” of teaching and coaching offered a more stable existence than the itinerant, non-remunerative life of a pro baseball player. He retired at age 25.

He was a high school teacher and coach before accepting the position at Bates. Over the years, he stayed in contact with Sukey. “Clyde would often just show up at our games at Bowdoin or Colby,” he said. “He loved to go to games. And when I was inducted into the Maine State Baseball Hall of Fame in Portland, Clyde attended the ceremonies. I appreciated that.”

Flynn’s estimate of Sukeforth as a baseball mentor and person is unequivocal: “Just a wonderful guy: outgoing, positive—loyal, modest, easy to be around. He loved Maine, fished, put out a few lobster traps, always had boats and dogs. He really enjoyed the outdoors. He lived a good life.”36

THE PIRATE YEARS

After scouting Robinson and recommending Branca, the third most notable event in Sukeforth’s baseball life was his participation in the drafting of Roberto Clemente, the first great hispanic star.

The Rickey tenure in Pittsburgh were years of little success for the Pirates. They finished last in the eight-team National League in 1954, so had first pick in the draft the following winter. The Pirates could claim players from other teams who were not protected on major league rosters. Rickey sent Sukey to look at African American pitcher Joe Black, who had been sent to the minors after a stint with the Dodgers. As usual, Sukey got to the park early and saw another prospect taking flies in the outfield. “I get to my seat to watch Montreal take infield practice and I see this baby-faced negro boy in right field with one of the greatest arms you have ever seen.”37

However, this outfield prospect was playing only sporadically.38 Sukeforth deduced that the Dodgers were “hiding” him. “The moment I saw Clemente I couldn’t take my eyes off him. I recommended we draft Clemente and he cost us only $4000 at the time.”39

Clyde stayed on with the Pirates until the end of the 1957 season. In the middle of that season, the Pirates fired manager Bobby Bragan, and again Sukey was offered the opportunity to manage in the major leagues. Again, he declined. This time he recommended Danny Murtaugh—a good choice as it turned out, as Murtaugh managed the Pirates on three different occasions for 15 years total, before succumbing to a stroke at age 59 in 1976.

This time Sukeforth had Christmas trees to grow. He told sportswriter Les Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press, “I never was cut out to be a manager, especially in the big leagues. You might say I’m not that ambitious, but the real reason is I couldn’t take what the job demands. I wouldn’t care for the speeches I’d have to make, the public appearances I’d have to make, or the worry or the heartaches that go with the job.

“I don’t ask for a lot out of life, but I do want contentment. I could never find it as a manager. I have a happy home life, own a farm in Waldoboro, Maine, and among other things I grow up there are Christmas trees.”40

So he went back to his farm intending to live happily ever after—and did so, at least until 1963, when he got “itchy” as he put it, after seeing some baseball pals in Florida in the offseason. Again he heeded the call of the Pirates to spend his summers with their prospects, coaching in Columbus, Georgia, in 1963, scouting in 1964, and managing in Gastonia, North Carolina, in 1965. “I enjoyed that,” he told Mike Shatzkin in an interview in 1993. “I don’t mind managing in those lower minor leagues. Kids.”41

So he retired for good at age 64 in 1966 and then lived happily ever after in Maine. Well, not exactly. For the next eight years, 1966–74, Clyde was a New England and Canada scout for the Atlanta Braves in northern New England and the Canadian Maritimes. This scouting duty he could perform from his home base in Waldoboro, where he lived with his second wife, Grethel, whom he married in 1951.

With the Expos recently installed in Montreal, creating a stir in Eastern Canada, Clyde was taken with the thought that some prospects might emerge from this unlikely northern clime: “They don’t ride the bus to and from school,” he said, “and they shovel their own snow off the pond. They are bigger, stronger, and can run better. I have an idea that in a few years, if baseball continues to develop the way it is, we’ll be seeing a lot more of these boys in baseball.”42

Clyde finally gave up a formal role in the game at age 72. He lived in retirement for 26 more years, almost all of them with Grethel, his wife of nearly 48 years, who predeceased him by two years, and his beloved dogs, in that cottage by the salt-water river just below town.

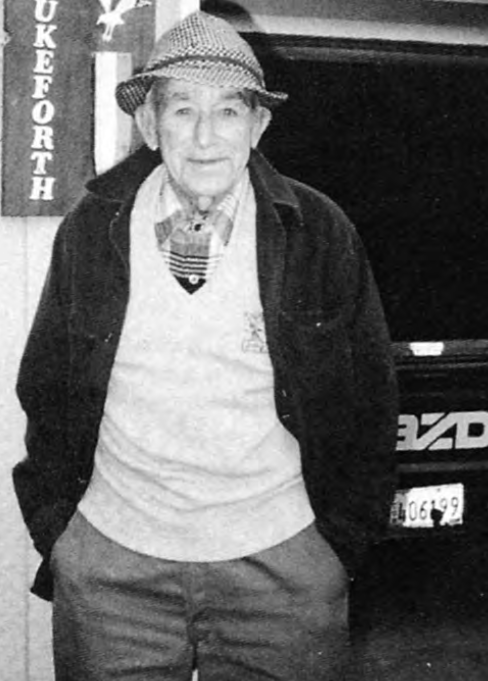

Clyde Sukeforth at age 90 (COURTESY OF THE SUKEFORTH FAMILY)

BASEBALL — AND MAINE

So here’s Clyde Sukeforth, the mentor of the immortal Jackie Robinson, the right-hand man of Branch Rickey, trusted and respected by all who knew him as a person of integrity and humility, whose life spanned nearly the entire twentieth century.

In the rich narrative of this long life lived well, two themes powerfully emerge—his love of baseball and his love of Maine. In 1995, he told a reporter for the Rockland (ME) Courier-Gazette, “I just like the game and the atmosphere. I felt at home at the ballpark. I never had to work in a factory. I’ve made a living doing what I wanted to do. (Baseball) has been my life and it’s been a great life.”43

Clyde Sukeforth—Mainer through and through, a Yankee, and a credit to his place.

KARL LINDHOLM, PH.D teaches in the American Studies Program at Middlebury College where he is Dean of Advising Emeritus. His classes include “Segregation in America: Baseball’s Negro Leagues.” He has published widely on baseball topics and is near completion on a biography of William Clarence Matthews, “Harvard’s Famous Colored Shortstop.”

Notes

1 Holmes, Tommy, “Clyde Sukeforth Sets a Record,” clipping, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, April 2, 1945.

2 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 66.

3 Bangor Daily News, October 12, 1994, C4; also, Bill Madden, “Sukeforth in right place at right time: Maine native helped bring Robinson to major leagues,” undated clipping, New York Daily News. Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

5 Mike Shatzkin, Interview with Clyde Sukeforth, Baseball Library.com, September 19, 1993; also C.E. Lincoln, “A Conversation with Clyde Sukeforth” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1987, 72–73.

6 Nick Wilson, Voices from the Pastime: Oral Histories of Surviving Major Leaguers, Cuban Leaguers, and Writers, 1920–1934, Clyde Sukeforth Interview, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2000, 40.

7 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 371.

8 Les Biederman, “Pilots Get Ulcers, Sukey to Raise Christmas Trees, clipping, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, August 21, 1957.

9 Letter from Helen Zimmerman to Karl Lindholm, November 30, 2008.

10 Will Anderson, Was Baseball Really Invented in Maine? Sukeforth interview, 1990. (Portland, Maine: Will Anderson, 1992), 119.

11 Clyde Sukeforth Oral History, Maine Memory Network, University of Southern Maine Center for the Study of Lives, 1998. http://www.mainememory.net/media/pdf/8617.pdf

12 Clyde Sukeforth Oral History, Maine Memory Network, University of Southern Maine Center for the Study of Lives, 1998. http://www.mainememory.net/media/pdf/8617.pdf

13 Ken Waltz, “Baseball Man: Sukeforth’s Love of America’s Pastime Spans Generations,” Rockland Courier Gazette, ca. 1994, clipping, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

14 Nick Wilson, Voices from the Pastime, 35.

15 Sukeforth Oral History, Maine Memory Network, University of Southern Maine.

16 Sukeforth Oral History, Maine Memory Network, University of Southern Maine.

17 “Sukeforth of Reds is Best-Hitting Catcher,” clipping, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

18 Brent Kelley, “Clyde Sukeforth and Baseball History,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 18, 1994, 180.

19 Ken Waltz, Rockland Courier Gazette.

20 Brent Kelley, Sports Collectors Digest; also Bangor Daily News, October 12, 1995, C4.

21 Nick Wilson, Voices from the Pastime, 37.

22 Bangor Daily News, October 12, 1995, C4.

23 Unidentified Montreal newspaper, February 15, 1940, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

27 Unfortunately, Picinich died the next year of pneumonia, at 46.

28 Unfortunately, Picinich died the next year of pneumonia, at 46.

29 Unfortunately, Picinich died the next year of pneumonia, at 46.

30 Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass was Real (Coward-McCann & Geoghegan, 1975), 184.

31 Nick Wilson, Voices from the Pastime, 37.

32 Jeane Hoffman, “Satisfied with Home, Bankroll, Sukeforth Relishes Placid Career,” New York Journal-American, April 18, 1947, 22. Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

33 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey, 461.

34 Randy Schultz, “Clyde Sukeforth: Former Player, Coach and Scout Played Roles in Jackie Robinson’s Signing and ’51 N.L. Pennant,” Baseball Digest, July, 2005.

35 Interview with Bob Flynn, Fall, 2009. Flynn was the author’s high school baseball coach.

36 Interview with Bob Flynn, Fall, 2009. Flynn was the author’s high school baseball coach.

37 Les Biederman, “Columbus Coach Sukeforth Recalls Nixing Pirate Job,” Pittsburgh Press, March 22, 1963, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

38 The Clemente story is well told by Sukeforth in Donald Honig’s Baseball When the Grass was Real, 182–4.

39 Biederman, “Columbus Coach Sukeforth Recalls Nixing Pirate Job.”

40 Les Biederman, “Pilots Get Ulcers, Sukey to Raise Christmas Trees,” Clipping, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, August 21, 1957.

41 Mike Shatzkin, Interview with Clyde Sukeforth, 1993.

42 Sukeforth, “Ex-Catcher, Seeks Talent on the Ice,” clipping, Sukeforth file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library October 27, 1970.

43 Ken Waltz, Rockland Courier-Gazette, 1994.