Cricket and Mr. Spalding

This article was written by Tom Melville

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, No. 16 (1996).

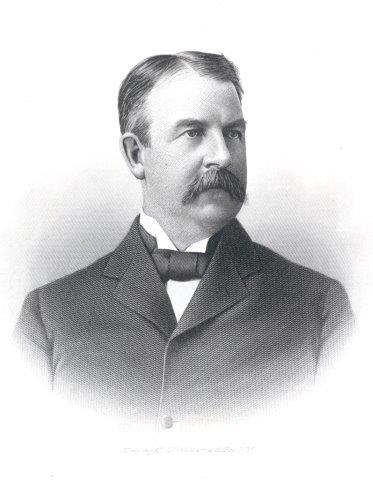

As much as any other figure in baseball history, Albert Goodwill Spalding (1850-1915), the Rockford-raised star pitcher, manager, and owner of the Chicago White Stockings (predecessors of today’s Chicago Cubs), and the founder of the sporting goods company that bears his name, was most responsible for making professional baseball what it is today.

As much as any other figure in baseball history, Albert Goodwill Spalding (1850-1915), the Rockford-raised star pitcher, manager, and owner of the Chicago White Stockings (predecessors of today’s Chicago Cubs), and the founder of the sporting goods company that bears his name, was most responsible for making professional baseball what it is today.

Though baseball history has long credited William Hulbert, the Chicago coal merchant and founder of the White Stockings, as the architect of the National League, which, in 1876 successfully wrested control of organized baseball away from players to owners, Spalding, his close associate, helped guide the league through its early organizational difficulties, and tirelessly worked to elevate the game into a pastime “worthy of the patronage, support and respect of the best class of people.”1

For much of his Chicago baseball career, however, Spalding was also associated with another, much less well-known sport, cricket, an association that not only underscored the insecurity of baseball’s public image during the late nineteenth century, but also indirectly influenced Spalding’s own vision of what baseball should be in American society.

Popular enough with Americans in the 1850s to be heralded, in some sporting circles, as the country’s national-sport-to-be, cricket had been quickly displaced by baseball as the country’s bat-and-ball sport of choice after the Civil War, the casualty of America’s apparently instinctive preference for a rapid transition, “high pressure” game, rather than one, like cricket, that had traditionally emphasized social propriety as much as actual competitive results.2

Nonetheless, cricket was still England’s national pastime, a sport that enjoyed the prestige of being patronized by “dooks and lawds,” a status it held primarily on the strength of its image as the epitome of the amateur ideal, which held that sport should be played and enjoyed as an end in itself, rather than for any extraneous rewards.

The refined sport

It was an image that was able to gain for cricket a modest, but sustainable, following among the more status-conscious segments of late nineteenth-century American society, especially those who still looked to England as the model of social propriety. At a time when golf and tennis had not yet arrived on the United States sports scene, cricket was the closest America had to a “gentleman’s game,” one that respectable Americans were more willing to identify with than baseball, whose reputation during this period was blackened by a succession of gambling scandals, ballpark riots, and owner-player disputes. Even John Montgomery Ward, one of the era’s most influential professional players, speaking at a dinner for New York’s Cosmopolitan Cricket Club in 1889, believed baseball, in comparison to cricket was becoming too violent a sport.3

Not surprisingly, the exclusive suburban cricket club, rather than the local ballpark, became the center of activity for many sports-minded upper-class Americans during the last decades of the nineteenth century, the most notable examples being Philadelphia’s Germantown Cricket Club, Boston’s Longwood Cricket Club, New Jersey’s Seabright Lawn Tennis and Cricket Club, and New York’s Staten Island Cricket Club, all of which allowed high society the alternative of a relaxed, highly social weekend of cricket to a frequently unsettling afternoon at the local baseball park.4

Cricket in Chicago

In Chicago, cricket began to attract interest as a focal point of high society in 1876, the year the old Chicago Cricket Club, which had enjoyed a moderately active, though not necessarily prestigious, existence before the Civil War,5 was reorganized on the impetus of a number of the city’s Canadian residents, especially the Toronto-born dentist, Dr. E. J. Ogden.6

By the early 1880s the club had set itself apart as the wealthiest and most exclusive of the city’s half-dozen cricket clubs, with an admission policy that carefully screened applications to exclude “all objectionable persons.”7

It was an arrangement that paid handsome dividends. By 1885 the club had over 150 members, and within a few years could number among its membership, such prominent Chicago figures as Marshall Field, General Philip Sheridan, Stuyvesant Fish, president of the Illinois Central Railroad, Charles Hutchinson, president of the Chicago Board of Trade, Carter Harrison, the city’s five-time mayor, and meatpacking baron Philip Armour, who even granted the club use of his personal property at 63rd and Indiana.8

To further enhance its status, the club incorporated in 1889 on the capitalization of $50,000 (a surprisingly large sum, fully half the amount the White Stockings incorporated with three years later) and, the following year, erected an impressive all-purpose clubhouse on seven acres of land at Stoney Island Avenue and 71st Street, which, in addition to its cricket ground, also had a state-of-the-art bicycle track and athletic field.9

Spalding seems to have been associated with the Chicago Cricket Club as early as 1880, the year he first appears as a member of the club’s standing committee.10 His involvement with the club, however, was not merely honorary.

He was a playing member of the club team that toured Canada the following year, and was even selected for the All-Midwest team that was to play a team of touring English cricketers at St. Louis that fall, a match that was eventually rained out.11

When the club incorporated Spalding was among the select inner circle of investors who held more than $500 of its stock, and a year later donated, in his name, a prize cup to be awarded annually to the winner of the city’s newly organized cricket league.12

“An elegant and cultured gentleman”

Why Spalding, one of the country’s prominent baseball figures, should have been so directly and openly involved with cricket, even to the point of admitting that England’s national sport had some features “which I admire more than I do some things about Base Ball,” is not hard to explain.13

Having assumed the presidency and part ownership of the White Stockings on Hulbert’s death in 1882, and already the owner of a thriving sporting goods business, Spalding had by this time completed the transition from the camp of “labor” to “capital.”

With this newly acquired status, it was clearly in Spalding’s interest to be associated with a sports organization more closely identified with the movers and shakers of Chicago society than baseball, which may have been his bread and butter in the workaday world, but was not something a status-conscious businessman would want to exclusively associate with on his own time, especially for someone like Spalding, who, despite his middle-class roots, seems to have prided himself on being “an elegant and cultured gentleman.”14

Spalding, however, also seems to have kept tabs on England’s national game as part of his grander scheme to make baseball more than just a game for Americans.

His first brush with cricket, in fact, probably came when his old Boston Red Stockings club, in conjunction with the Philadelphia Athletics, toured England in 1874, a scheme that had been hatched by Boston manager Harry Wright to bring baseball to the attention of English society.

Sent to England that winter to work out the details of the tour, Spalding quickly realized that America’s fledgling national game stood little chance of being accepted in England unless it could win favorable comparison to cricket. Always the opportunist, Spalding quickly took it upon himself to arrange with English sports authorities a number of cricket matches, so many, in fact, that the American baseballers actually ended up playing as much cricket as they did baseball during the tour.15

Spalding seems to have planned to use this same approach for his own, more ambitious, around-theworld baseball tour of 1888-89, even going so far as to persuade his old Red Stockings teammate George Wright, an experienced cricket player, to come along and, using an improvised batting cage, coach his White Stockings at cricket during their long Pacific crossing to Australia. Spalding himself even joined some of these practice sessions, one reporter noting that “standing before a wicket, he is the picture of manly strength and grace.” His plan, however, did not seem to go over too well with the baseballers themselves, and after only a single match in Sydney, they played no more cricket during the tour, not even in England.16

Spalding was no more successful in his efforts to win the Anglo-Australian world over to baseball in 1889 than he had been in 1874, and following an unsuccessful attempt to personally organize an English baseball league in the 1890s, probably realized that cricket, rather than being a window of opportunity, was, instead, an immovable barrier to his grand dream of making baseball “the universal athletic sport of the world” (which, in his eyes, meant only America, Canada, England, and Australia).17

Spalding himself attributed this failure to the different roles cricket and baseball played in their respective cultures. There was little hope, he claimed, that baseball would ever be accepted by upper-class English society because it was “a game for the people,” while cricket “is essentially a game for the aristocracy.”18

For all baseball’s popularity as the “people’s game,” Spalding also seems to have believed that it had to shrug off its image as a hotbed of rowdyism, and incorporate some Old World, upper-class moral constraint into its energetic, New World “pluck and drive,” before it could completely and unconditionally become the national game of every American, from the roughest corner sandlot to the most exclusive suburban country club. It’s a condition, baseball has long since come to realize, that is not necessary for its national prosperity.

Further Reading

George Kirsch, The Making of American Team Sports: Baseball and Cricket, 1838-1872 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989).

A.G. Spalding, America’s National Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992).

Notes

1 Peter Levine, A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 51.

2 Robert Lewis, “Cricket and the Beginning of Organized Baseball in New York City,” International Journal of the History of Sport (December 1987): 327.

3 “Gentlemanly Sports,” New York Tribune, October 31, 1879: 4; “The Base Ball Business,” Western Monthly (Chicago), vol. 4, 1870: 328-9; American Cricketer, September 12, 1889, 81.

4 Will Roffe, “Cricket in New England and the Longwood Club,” Outing, June 1891: 251-4; Charles Clay, “The Staten Island Cricket and Baseball Club,” Outing, November 1887: 99-112; John Lester, A Century of Philadelphia Cricket (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951), 213-18.

5 A. T. Andreas, History of Chicago vol. 2 (New York: Arno, 1975), 613-14; Chicago Tribune, August 18, 1856: 3; May 26, 1857: 1; May 20, 1876: 5.

6 A. T. Andreas, History of Chicago, vol. 3: 681-2.

7 Daily Inter-Ocean, June 1, 1890: 3.

8 A. T. Andreas, History of Chicago, vol. 3: 682; Daily Inter-Ocean, June 1, 1890: 3; May 8, 1883: 5.

9 Daily Inter-Ocean, June 1, 1890: 3; Peter Levine, A. G. Spalding, 37.

10 New York Clipper, August 27, 1881: 363.

11 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 11, 1881: 6.

12 Daily Inter-Ocean, June 1, 1890: 3; Chicago Tribune, June 13, 1891: 6.

13 A. G. Spalding, America’s National Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 6.

14 Peter Levine, A. G. Spalding, 124.

15 New York Clipper, August 22, 1874: 163; September 5, 1874: 183.

16 New York Sun, December 31, 1888: 3; Daily Inter-Ocean, January 21, 1889: 9.

17 A. G. Spalding, Baseball, 611, 612.

18 Ibid., 609.