Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas

This article was written by Frank Jackson

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 26, 2006)

Several years ago when the Texas Rangers explored the idea of moving their spring training headquarters from Port Charlotte, Florida, one option they briefly considered was building a spring training complex in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Of course, for the move to be feasible, at least three other teams would have to be persuaded to go along to provide competition for exhibition games.

The Houston Astros were a natural for the Rio Grande Valley, as they were the closest (about 350 miles) major league team to the area. But would anybody else be interested? As it turned out, nobody was, so the idea died a quick death. The Rangers (along with the Kansas City Royals) went to Surprise, Arizona; the Astros chose to renovate their existing complex in Kissimmee, Florida, and nobody came to the Rio Grande Valley for spring training. But in the early years of the 20th century, spring training in Texas was hardly an unusual proposition.

Spring training was not meticulously chronicled in early years of professional baseball, but preseason trips to warmer climes have a history almost as long as organized baseball itself. The first trip to Florida was made by the Washington Capitals, who set up shop in Jacksonville in 1888. In 1886, Cap Anson, a staunch believer in preseason preparation, took his Chicago White Stockings to Hot Springs, Arkansas, a popular locale for a number of teams well into the 20th century. The White Stockings and the Cincinnati Red Stockings took trips to New Orleans in 1870, the first time two teams were in the Crescent City. The powerful Reds defeated the local Pelicans, 51-1, on April 25 of that year.

The teams that headed south played themselves into shape not just against each other but also against local talent, including minor league teams1 and college teams, thus presenting a great opportunity for young players to make an impression on major league managers. To a certain extent, the level of competition was determined by the other major league teams training nearby. In 1917, however, when the White Sox were training in Mineral Wells, Texas, Charles Comiskey decided his team’s confidence could be enhanced by scheduling only minor league opponents, even though the Cardinals, Giants, Browns, and Tigers were then all training in Texas. That might not appear to be sound preparation for the regular season, but it obviously didn’t hurt the White Sox, as they were World Series champions that year.

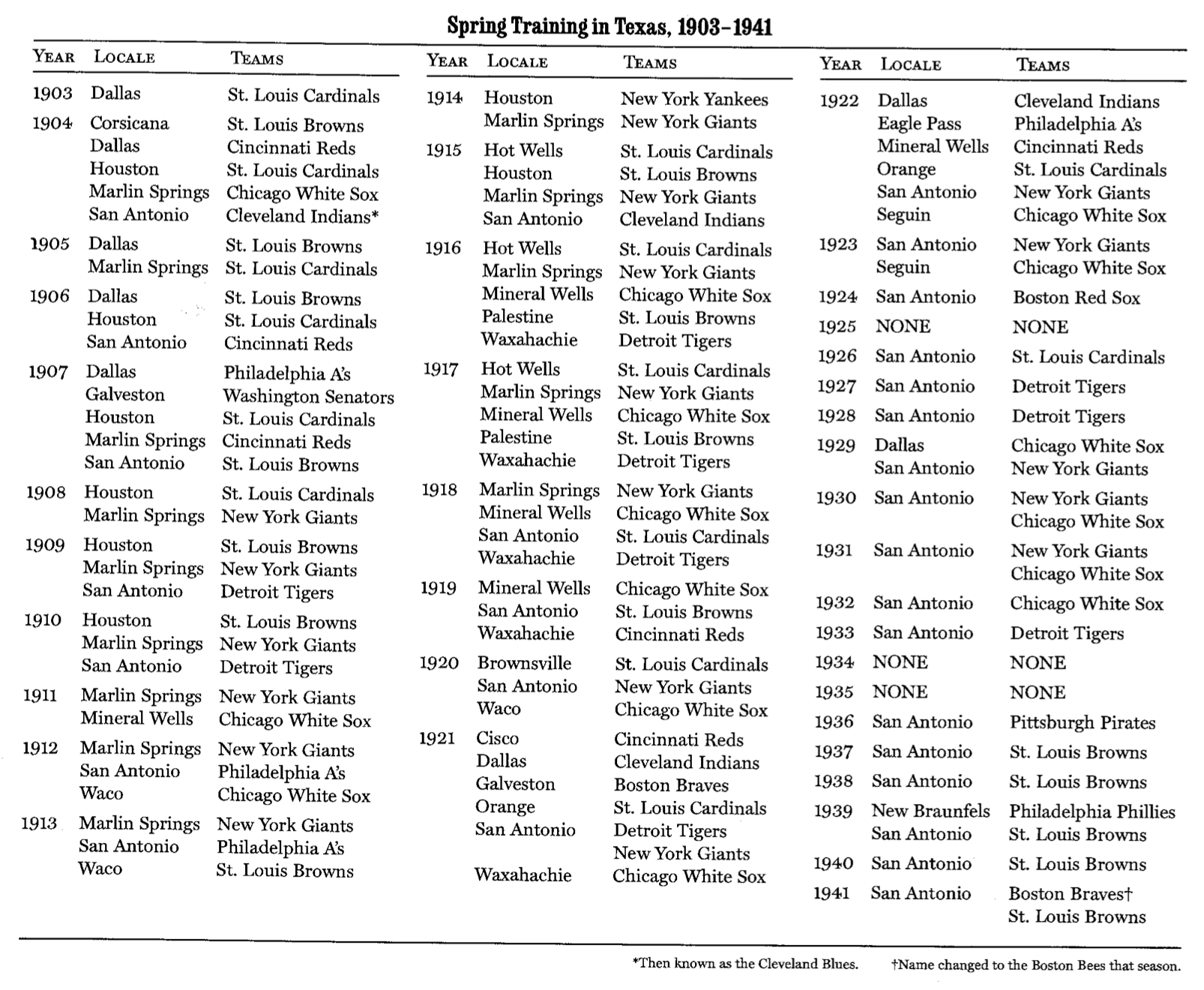

During its heyday in Texas, spring training had at least as much in common with barnstorming as it did with spring training as we know it today. Then, as now, it provided an opportunity to evaluate rookies and other unknowns (or “Yannigans”) before the regular season rosters had to be drawn up. Perhaps most important, from a fan’s point of view, it gave people in the hinterlands their only opportunity to see major league ballplayers plying their trade. Whatever the vagaries of springtime pilgrimages in the 19th century, by the early years of the 20th century, spring training in some form or fashion was an established fact of life for all major league ballplayers. From 1903 to the eve of World War II, Texas was a popular destination for major league teams in search of spring training facilities. Of the 16 major league teams in existence from 1903 to 1941, only two teams, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Chicago Cubs, never trained in Texas.

The Rio Grande Valley, with its palm trees and citrus groves, embodies the subtropical ideal for spring training, yet aside from one season (1920 in Brownsville), it did not figure in major leaguers’ plans.

In the early years of the 20th century, the Valley was largely undeveloped, except for Brownsville, which dates back to 1846 and the establishment of Fort Brown during the Mexican War. The city hosted minor league baseball (the Brownsville Brownies of the Southwest Texas League) as early as 1910. The rest of the Valley didn’t begin to grow until midwestern farmers, attracted by the year-round growing season, headed south to see what crops their skills could coax from the south Texas soil. Harlingen and Edinburg, which have hosted independent minor league baseball in recent years, were not even on the map in the first decade of the 20th century. Harlingen was not incorporated till 1910, Edinburg a year later.

Minor league baseball did not reach Edinburg till August 1926 (when the Victoria Rosebuds relocated there) and Harlingen till 1931 (Rio Grande Valley League), and by that time the golden age of spring training in Texas had passed. For the record, the Valley also hosted minor league teams in Mission, San Benito, and McAllen in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

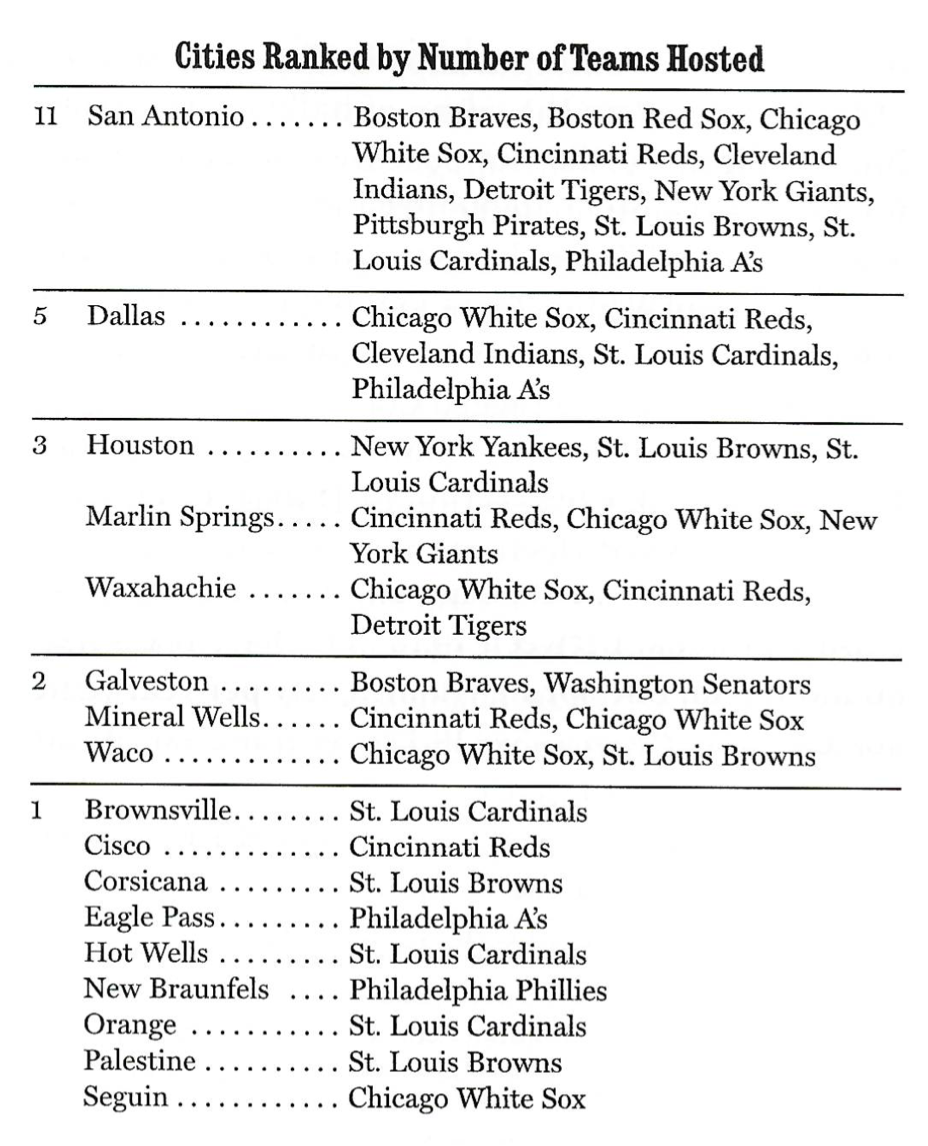

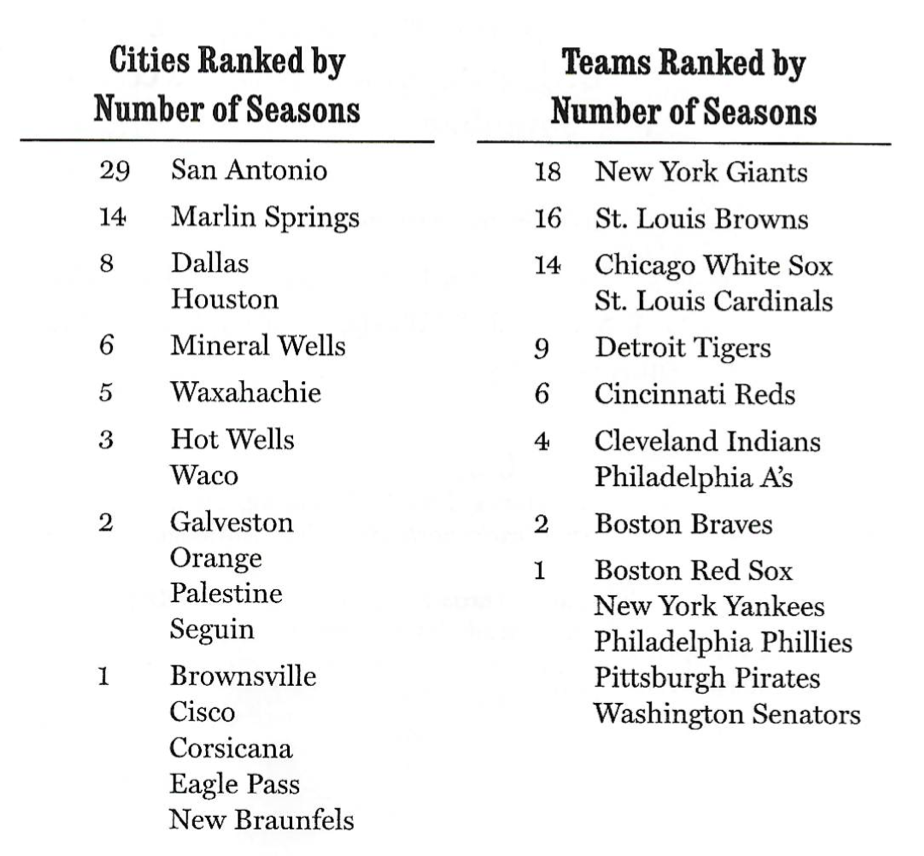

If the Rio Grande Valley was too remote and undeveloped for spring training in the early years of the 20th century, the state of Texas offered many other options. Even with its wide-open spaces and wild reputation, Texas had no shortage of “civilized” locales for major league teams in search of sunshine and warm temperatures. The most popular host city was San Antonio, one of the oldest cities in Texas and, until the 1920s, the largest. The Alamo City hosted 29 seasons of spring training, including 10 of the 14 teams that ventured to Texas. Surprisingly, after San Antonio the most popular location was the small town of Marlin Springs (now known as merely Marlin), a resort town 26 miles southeast of Waco. The New York Giants were particularly fond of the town, as they trained there in 1908-1918. Like Mineral Wells, west of Fort Worth, and Hot Wells, southeast of San Antonio2, the town catered to tourists who came for the healing waters.

To anyone familiar with Texas history and geography, the lineup of towns and teams presents many tantalizing questions. For example, why was the established seaside city of Galveston given short shrift — a mere two seasons? Perhaps the answer lies with the weather. The Galveston hurricane of 1900 — still the most deadly natural disaster in American history — had surely embedded itself in the national consciousness, but even lesser storms had made their mark. One such storm on August 15, 1915, destroyed the ballparks in Galveston and Houston, and the Galveston Sandcrabs and Houston Buffaloes rerouted their “home” games to Brenham, Austin, and Corpus Christi. That was the end of spring training in Houston, and Galveston hosted but one more season (1921). Of course, tropical storms still present a major problem for spring training facilities in Florida, as the 2004 hurricane season proved, and have probably played a key role in the increasing popularity of Arizona.

Other Texas Gulf Coast towns fared poorly as spring training locations. Corpus Christi — a fairly large port city similar in atmosphere and climate to Florida — was never selected for a spring training site, even though the city had hosted minor league ball as early as 1910 (the Corpus Christi Pelicans of the Southwest Texas League). Orange was limited to two seasons (1921 and 1922) and Brownsville to one (1920). While the avoidance of coastal cities may be understandable, it is difficult to fathom the total absence of Austin and Fort Worth, inland Texas League cities that were certainly capable of hosting major league teams in the spring.3 Perhaps the ultimate puzzler is the appearance of the Philadelphia A’s in the remote border town of Eagle Pass in 1922. What was Connie Mack thinking?

It’s easy to see why Texas was so popular with the Browns and Cardinals, as St. Louis was the closest major league city to the Lone Star State in the first four decades of the 20th century. Other teams based in the Midwest — the Cubs, White Sox, Tigers, and Reds — were not much farther away. But why were the Giants — who spent 18 springs in Texas, more than any other team — so fond of the state? Couldn’t they have found something back east a little closer to home? Here we must introduce Giants manager John McGraw and the key role he played in spring training history.

As a member of the Baltimore Orioles in 1894, McGraw attended an intensive eight-week spring training camp in Macon, Georgia, under manager Ned Hanlon. The players were drilled endlessly on the hit-and-run play and the Baltimore chop, among other “small ball” tactics. The results were immediately apparent once the season began.

After a mediocre 1893, when the Orioles finished with a 60-70 record, eighth in a field of 12 teams, they came out swinging (sometimes literally) in 1894. They won 34 of their first 47 games, but did not clinch the pennant until September 28. Other teams couldn’t help but notice that the seeds for the Orioles’ successful season had been planted in Macon in the spring.

Without that fast start in April, the Orioles would not have won the pennant. The lesson was obvious: a leisurely spring training was no longer an option for a major league team seriously bent on contending.

When McGraw became manager of the New York Giants, he remained convinced that players should peak in the spring to be ready for the opening of the season. During his first spring training with McGraw at San Antonio in 1920, Frankie Frisch had one of his earliest tiffs with the Giant manager. “I woke at seven and walked four miles to the field,” recalled Frisch.”At nine, I jogged five laps. I hit, fielded, threw, and slid until noon. Then I lunched, hit, fielded, threw, and slid until dusk. Then I walked four miles back to the hotel.” A rigorous regimen, to be sure — and not subject to the slightest modification.

One day when Frisch hitchhiked back to the hotel for lunch, his meal was interrupted by an irate McGraw, who fumed, “You rockhead. Next time I catch you riding anywhere I’ll fine you five bucks a mile. You know what legs are for … baseball.”

To that end, McGraw’s first foray into Texas was to Marlin Springs in 1908. He returned every year through 1918. Today, a town of about 6,400, in those days it was home to about 4,000 people. While not exactly “the sticks,” it was a long way from New York City in more ways than one. But McGraw was looking for a place where his men would find few distractions from their baseball discipline. Marlin Springs was big enough to provide good rail service to Dallas, Fort Worth, Waco, and other cities where the Giants could play exhibition games against Texas League teams. Since the town catered to tourists, it had hotels, a Hilton and the Arlington,4 suitable for major league ballplayers. This was an important consideration for the status-conscious McGraw, who insisted his ballplayers were not second-class citizens, no matter what the more respectable elements of society said.

Considering the large quantities of alcohol imbibed by players of that era, the elimination of toxins might have been a key factor in the selection of a spring training venue. This would explain why Marlin Springs and other towns with spas were so popular. Since many Texas counties were (and still are) dry, the difficulty of buying liquor might have made some remote Texas towns particularly attractive as spring training sites before Prohibition. On the other hand, New Orleans was also a popular spring training locale, and a venue more conducive to boozing could hardly be found in the Deep South or anywhere else.

Then as now, a sweetheart deal with a municipality was a big inducement to a team in search of a spring home. In 1910, Marlin Springs deeded the local ball park, Emerson Field, to the Giants for as long as they trained in Marlin, which turned out to be another nine years. The Giants actually controlled the property until the 1970s.

The annual presence of the Giants, the “glamour” team of major league baseball during McGraw’s reign, was a big event in the social life of Marlin Springs, though some of the town’s leading families would not allow their daughters to socialize with the ballplayers. Fish fries and community dances were recurring events, and the Giants frequently played intra-squad games to benefit local charities.

In small Texas towns, the annual springtime sojourn of major leaguers provided a publicity boost that similarly sized hamlets could only dream of. Today it taxes the imagination to envision Ty Cobb sitting in the lobby of the Rogers Hotel (still standing) in downtown Waxahachie5, Joe Jackson going out for a bite to eat in Mineral Wells, or Christy Mathewson playing checkers with the locals in Marlin Springs. But these legendary figures and many other major leaguers of lesser repute were regular seasonal visitors to small towns in the Lone Star State.

The figures that dominated the headlines during the regular season also did so during spring training. Since the outcome of the games was of little importance, many of the more entertaining anecdotes from Texas spring training history are not from the games themselves but from game-related events.

During the Giants’ final spring (1918) in Marlin, the Giants played a team from the Waco Air Service Pilot Training Center. Doubtless more entertaining than the game itself were the pilots performing stunts in biplanes above the field. John McGraw himself donned helmet and goggles for a 20-minute flight to Waco. This was possibly the first time a major league manager rode in an airplane.

One historic first took place when the Giants played their first night game during spring training in San Antonio in 1931. After witnessing a rookie outfielder undergo a coughing spasm due to inhaling insects attracted by the artificial lighting, McGraw, ever the canny strategist, advised his troops, “One thing to remember. You must keep your mouth shut when you play these night games.”

Sometimes the games were eclipsed by off-the-field activities, such as Rube Marquard firing a pistol at a billboard outside his Marlin Springs hotel room — an act frowned upon even in Texas and necessitating a visit from the local peace officer. The Falls County sheriff attempted to arrest Marquard, but he backed down after McGraw intimidated him by asserting, “The Giants put this town on the map, and the Giants can just as quickly wipe it off by leaving.”6

The best chronicled event in Texas spring training history was probably Ty Cobb’s set-to with Giants second baseman Buck Herzog. The rhubarb happened during spring training in 1917, when training camps in Texas, as well as other locales, were the scene of ballplayers engaging in military drills, supposedly to prepare them for America’s anticipated entry into the Great War.

The Giants and Tigers had set a string of exhibition games to be played in Texas and points north as the two teams made their way home after their training camps closed. Herzog ragged Cobb about showing up at the last minute for an exhibition game at Gardner Park in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. Cobb took offense and spiked Herzog at the first opportunity. A brawl broke out, the dugouts emptied, and the cops stormed the field.

That evening at a banquet at the Oriental Hotel, Herzog challenged Cobb to fisticuffs and was soundly trounced by him in the latter’s hotel room. A confrontation between Cobb and McGraw took place the next day in the hotel lobby. Realizing he could be a marked man for the rest of the exhibition series, Cobb refused to play in any more games until the regular season began. While he trained with the Cincinnati Reds, the Tigers and Giants continued the exhibition series, punctuated by occasional scraps. Though the teams played in different leagues, the bad blood remained.

Four years later, when both teams were training in San Antonio, the teams were still not on speaking terms, even though they were headquartered just blocks apart downtown and civic leaders were imploring them to stage exhibition contests. McGraw said he would not play unless Cobb, who had just been named Manager of the Tigers, came to him in person and requested the matchup. Cobb refused, so that was that. This was despite the fact that Hughie Jennings, the former Detroit manager who had joined the Giants coaching staff, could have served as a go-between. Ironically, it was not until the death of Jennings in 1928 that Cobb and McGraw spoke to each other again.

Since World War I had cut into baseball revenues in 1918, owners decided to cut costs and play a truncated schedule in 1919, preceded by a shortened spring training. In mid-March McGraw moved the Giants to the college town of Gainesville, Florida, for one spring. As in Marlin, however, he had secured a sweetheart deal: free use of the university facilities.

When fan interest returned during the 1919 season, the owners went back to business as usual, and McGraw returned to Texas for four years. This time, however, the Giants trained in San Antonio, which offered far more in the way of distractions than Marlin Springs.7 The team stayed at the Crockett Hotel — just a long fly ball from the Alamo and still a popular downtown destination. It might be that McGraw felt that San Antonio was now a “safe” location, given that Prohibition was in force. Actually, the city ofl62,000 provided more opportunities for procuring illegal brew. In 1923, McGraw levied an unprecedented number of fines. Most of the players could afford it, however, as McGraw boasted that he had 12 of the 14 highest paid players ( the exceptions were Rogers Hornsby and Edd Roush) in the National League.

During the early 1920s, it looked as though Texas had the potential to develop into a permanent site for spring training. Seven teams trained in Texas in 1921 and six in 1922. But in 1923 only two teams chose Texas, in 1924 only one, and in 1925 none.

Why did spring training drop off so drastically after 1922? In a word: Florida. With the help of boosters, notably Al Lang (for whom the waterfront ballpark in St. Petersburg was named), Florida and spring training quickly became synonymous. Thanks largely to two railroad magnates, John Plant on the Florida peninsula’s west coast and Henry Flagler on the east coast, rail service to Florida had improved greatly since the turn of the century. The increasing popularity of motorcars and the building of highways also played a major role in transforming Florida from an inaccessible wilderness to a tourist destination. As a result, Florida underwent a real estate boom in the 1920s and the rest of the nation — including major league club owners — couldn’t help but pay attention.8 Also, teams knew that those cold fronts that periodically swept over southern states (Texans call them “blue northers” or sometimes just “northers”) usually petered out before they got too far down the Florida peninsula, thus minimizing the games and practice time lost to bad weather in late winter and early spring.

By 1924, nine teams were training in Florida. The Grapefruit League that we know today was starting to take shape. Spring training in Texas and other Southern states wasn’t entirely dead, but the pulse was weak. Between 1926 and 1941, Texas had no more than one spring training city per year (and hosted no teams in 1934-1935), with the exception of 1939, when the Browns returned to San Antonio and the Phillies made their lone appearance (at New Braunfels) in the Lone Star State.

World War II finished off spring training in Texas. Travel restrictions forced teams to choose northern spring training sites close to their homes, but the annual Florida migration resumed after the war. Arizona also beckoned, as the Cleveland Indians and the New York Giants trained there for the first time in 1947. But spring training in Texas was history.9

If Texas was a popular destination for baseball teams during the early years of the previous century, could it make a comeback during the current century? Doubtless the smart money folks would never bet on the return of major league spring training camps to the Lone Star State. But stranger things have happened in baseball history.

FRANK JACKSON is not a native Texan, but has lived in Dallas for 30 years. He grew up rooting for the Phillies in the late 1950s and early 1960s, something he considers excellent preparation for becoming a Rangers fan.

Sources

Alexander, Charles C. John McGraw. New York: Viking, 1988.

Cataneo, David. Peanuts and Cracker Jack. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1991.

Evans, Wilbur and Bill Little. Texas Longhorn Baseball-Kings of the Diamond. Huntsville, AL: Strode Publishing, 1983.

Falkner, David. The Short Season: The Hard Work and High Times of Baseball in the Spring, New York: Penguin, 1986.

Fehrenbach, T.R. Lone Star. New York: Wings Books, 1991.

Frommer, Harvey. Baseball’s Greatest Managers. New York: Franklin Watts, 1985.

Graham, Frank. The New York Giants: An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002; originally published in 1952.

Holaday, Chris and Mark Presswood. Baseball in Dallas. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Press, 2004.

Holaday, Chris and Mark Presswood. Baseball in Fort Worth. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Press, 2004.

O’Neal, Bill. The Texas League, 1888-1987: A Century of Baseball. Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1987.

Torres, Noe. Ghost Leagues: A History of Minor League Baseball in South Texas. Tamarac, FL: Llumina Press, 2005.

Valenza, Janet Mace. Taking the Waters in Texas; Springs, Spas and Fountains of Youth. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2000.

Wilbert, Warren N. and William C. Hageman. The 1917 White Sox: Their World Championship Season, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004.

Texas 2005 State Travel Guide (Austin, 2005)

www.springtrainingonline.com

Notes

1 In the days before major league affiliation and vast spring training complexes, Texas was also popular with minor league teams — and not just Texas League teams — in search of suitable springtime digs. The Milwaukee Brewers and the Buffalo Bisons, among others, trained in Texas.

2 Hot Wells no longer appears on Texas maps. When the Cardinals trained there (1915-1917), it was just southeast of the San Antonio city limits and has since been absorbed by the city.

3 Though no major league teams set up camp in Austin and Fort Worth, the two cities hosted numerous exhibition games. At various times, the University of Texas Longhorns hosted the Cardinals, Browns, White Sox, Tigers, Giants, and Yankees at Clark Field in Austin.

4 Named after the famed Arlington Hotel in Hot Springs, Arkansas, the Arlington in downtown Marlin has since been razed and a post office was erected on the site.

5 Surprisingly, it is still possible to see baseball played on the field where the Tigers, White Sox and Reds trained. Now known as Richards Field (after native son Paul Richards), it is currently the home of the local high school team.

6 A 2005 visit to the forlorn streets of Marlin bears out McGraw’s prophecy. Aside from a faded mural on the outside wall of the town’s modest history museum, there is nothing to commemorate the 11-year presence of John McGraw and the New York Giants.

7 San Antonio was also attractive to McGraw because Hot Wells was accessible by streetcar.

8 McGraw himself became embroiled in real estate speculation in the Sarasota area, the winter home of his friend, circus impresario John Ringling. This was one factor in relocating the Giants to Sarasota during the 1924 and 1925 spring training seasons.

9 Preseason exhibition games, however, were not. In 1946, for example, the Pirates and White Sox, who had been training in California, played a series of exhibition games in El Paso, Del Rio, Houston, Dallas, and Fort Worth on their way home before opening day. Even today, preseason exhibition games are common if not annual occurrences, not just in Houston and Arlington, but in minor league cities like Midland and Round Rock.