Dave Nicholson, Revisited

This article was written by Mike Kaszuba

This article was published in Spring 2021 Baseball Research Journal

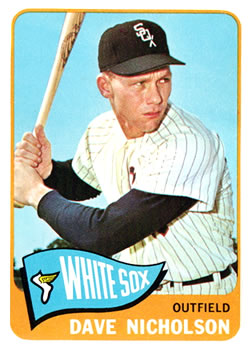

He was forever young on his baseball card—6-foot-2, with a square jaw, and a passing resemblance to Mickey Mantle. He was 24, and I was in the third grade. It was the summer of 1963.

He was forever young on his baseball card—6-foot-2, with a square jaw, and a passing resemblance to Mickey Mantle. He was 24, and I was in the third grade. It was the summer of 1963.

I never minded that he set a record for strikeouts in a single season that year, which is how many people—if they recall him at all—remember him. He was my guy, No. 11 in the black-and-white pinstripes. I grew up on the South Side of Chicago as a White Sox fan—a team with pitching, speed, and fielding, but little power—and Dave Nicholson was my home run hitter.

And now he was old, reeling from lung surgery. He sounded hoarse and tired. “I’m trying to recover,” he said on a Friday in January 2016, a half-century after he led the White Sox in home runs in his best season. But he was not very convincing. He had a chunk of his lung removed during a six-day hospital stay that ended on Christmas Eve; it was as big as his fist, he reported by phone.1

He was 76 at the time, and had once smoked a pack-and-a-half of cigarettes a day. I was retired, after 40 years as a newspaper reporter, and interested in finding out what happens to heroes. I had never met him in person, though my journey in the end would bring me to his doorstep.

I had gotten out of the hero worship business long before. Though I spent much of my time covering government for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, I had ended my career in journalism reporting on the money of sports—the endless appetite for new stadiums, the sweeping corporate takeover of sports, and the scandals both big and small. The athletes, instead of inspiring a small boy, were too often doing things that hardly made them heroes.

It had always been there, I suppose, but everything now seemed to be on steroids.

I was worried meanwhile that Nicholson was fading, and quickly. And, as I began an odd relationship with him, calling him every six weeks or so to check in, I hung on his every word.

It would go on for nearly two years—me calling, hoping to catch him in a talkative mood, and trying to get myself invited for a visit and a sit-down interview. Most times he talked, recalling in detail a long-ago home run or the latest inconclusive trip to the doctor. Occasionally, he was terse and nearly hung up, depressed because his energy was sapped, forcing him to sit in a chair most of the day.

“I am not feeling too good,” he told me during our fifth conversation, this one in February 2016. “I got about another nine weeks before I’m out of the woods. [I] haven’t been in a very good mood. I didn’t expect the kind of operation I had. I’ve been kind of in the dumps.”2

He rebounded but, nearly a year later, relapsed. I learned from Jeannie, his wife, that he was again in the hospital in late 2016. “I don’t like being alone,” she said, missing her husband. She had taken him golfing, hoping to get him more active, and feared she may have caused more problems.3

I first cold-called Nicholson on a gray Tuesday in October 2015—the first night of the World Series between the Kansas City Royals and New York Mets. He said he did not watch baseball very much anymore; didn’t like the way the game was now played. He was of course puzzled—skeptical, even—about what I wanted.

I told him I was interested in something more than an autograph. He laughed when he heard he was my childhood hero. I wasn’t very smart, he said.4

Dave Nicholson would never be confused with the era’s greats—Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, or Roberto Clemente. When he hit 22 home runs in 1963, he batted just .229. A year later, he was relegated to a part-time role. There would be no Ted Williams-type home run in his final at bat. In his last game, he went 0-for-3.5

When I talked to Gary Peters, the White Sox pitching ace during the early 1960s, he told me that he had occasionally pinch-hit for Nicholson when the slugger was scheduled to face a pitcher who was particularly tough on him. It was highly unusual—but, of course, classically White Sox—for a pitcher to bat in place of the team’s supposed power hitter. “I pinch hit for Dave a few times,” Peters said. “He didn’t like that very good. He had a lot of trouble with certain guys who had good sliders.” Peters, in fact, claimed he once hit a home run pinch-hitting for Nicholson.6

“He swung hard,” said Peters, who won 19 games for the White Sox in 1963, and was a 20-game winner for the team the following year. But Nicholson “couldn’t adjust for the breaking ball very good.”7

Rooting for Nicholson meant forgetting those kinds of things. But for one brief moment, it all came together—for me, and for him. It was the first summer that I lived and died with each White Sox game, often listening to them on a transistor radio on my front step in Calumet City with my best friend, Jerry Gorak. It was a Polish neighborhood, surrounded by steel mills and an oil refinery. The twin steeples of a Catholic Church, three doors away, loomed over our duplex; the Czechanski Funeral Home was across the street. On Sunday afternoons, my dad listened to live polka music on the radio from Club 505 in the nearby Hegewisch neighborhood of Chicago.

Against that background, I spent the summer worshipping a hitter who couldn’t hit.

One could always dream, though, and I kind of did. In the early 1960s, any real fan played Strat-O-Matic Baseball, a card and dice game that matched real players from real teams with surprisingly real results. It was addictive. My parents bought me the 1963 starter set: five teams—the New York Yankees, San Francisco Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, Los Angeles Dodgers and White Sox. A couple of years later I added three more, including the Chicago Cubs.

I purposely added the 1966 Cubs—being a White Sox fan, I hated the Cubs—knowing that in reality they had lost 103 games that year and would likely suck at Strat-O-Matic Baseball. They did not disappoint.

Nicholson did not disappoint either. In my league, Big Nick was a monster. He hit 53 home runs, including four grand slams, in 1966.

In 1967, the White Sox won the pennant by one game over the Giants in my league and Nicholson finished fifth with 37 home runs, two of them grand slams. My pretend White Sox, led by Nicholson, were way more satisfying than the real thing.

Not bad production, considering it was fictional. On his Strat-O-Matic card, there were 33 possible outcomes every time the dice were rolled. Of the 33, there were only five ways Nicholson could get a hit, and just a total of 10 ways he could get on base. On his card, meanwhile, there was more than a one in three chance he would strikeout. But the dice, for some reason, were kind to him.8

As I got married, moved to Minnesota, had a kid, got divorced, got married and had more kids, Nicholson faded from my consciousness but never completely disappeared. In the basement, my copy of Operation White Sox, the team’s 50-cent yearbook from 1964, had survived nearly six decades. Nicholson was pictured on page 123, rounding the bases. The write-up was glowing: “Dave, the $100,000 bonus baby sought by all in 1958, was part of the gigantic Baltimore-Chicago deal of the winter of 1962. He responded spectacularly 449 times at bat slamming 22 homers and driving in 70 runs.”9

My White Sox memories, though fogged slightly by time, remained vivid. There were the bus rides to Comiskey Park, sponsored by my dad’s American Legion post, which featured beer and pop on ice in a tub in the aisle. As we swept through the dingy South Side neighborhoods, and inched closer to the stadium, we ducked as kids threw rocks at our bus.

The old ballpark was cavernous, and smelled of beer and cigars. On humid nights, the players warmed up in a haze of cigarette smoke that hung over the field—this was, after all, the 1960s. Andy the Clown, who was always kind of creepy, roamed the stands as the team’s unofficial mascot. The exploding score- board was in straight-away center field.

Meanwhile, I sucked at baseball. In Little League, I was chubby, slow, and short—a bad combination. For some reason, I batted leadoff and often got on base by purposely getting hit by the ball. Our manager seemed to encourage me to lean into the pitch. Our team was sponsored by an A&W Root Beer stand, and we lost nearly all of our games.

I was the son of a Catholic fork-lift operator, and was taught to keep my head down and brace for disappointment. In that sense, Nicholson was the perfect hero—the guy who might win the game, but more than likely would not.

As I neared retirement, I found myself strangely circling back to Nicholson and a once-upon-a-time world.

And for any Nicholson fan, that meant heading to May 6, 1964. That was the night Nicholson hit a ball over the left field roof, and out of Comiskey Park. Only Jimmie Foxx, Eddie Robinson, and Mantle had ever done it before, or so the story went. The team estimated it traveled 573 feet—and into the hands of 10-year-old Mike Murillo Jr. who, according to the Chicago Tribune, was standing outside the stadium and listening to the game on the radio.10

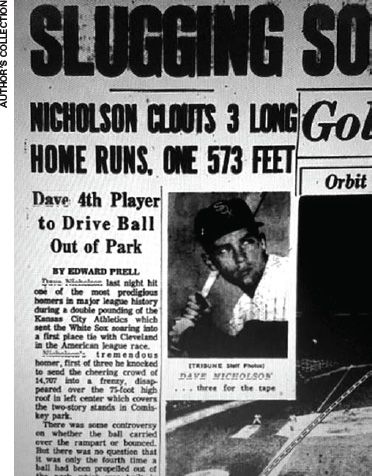

The newspaper called it “one of the most prodigious homers in major league history,” claiming that Nicholson’s home run was the second longest ever hit in the major leagues, behind only a 600-foot home run by Babe Ruth.11

Murillo gave the ball to Nicholson in exchange for one of Nicholson’s bats, an autographed baseball, and a picture with the slugger. The Tribune documented it all on the front page of the next day’s sports section.12 For a fleeting moment, Nicholson was the toast of the town.

But the controversy over Nicholson’s biggest moment started almost immediately. Fans in the left field upper deck claimed they heard a bang as the ball went over the roof, suggesting maybe it had bounced on the roof and did not go over on a fly. Still, the Tribune quoted John Cook, an electrician working on the roof that night, as saying the ball cleared the roof.13

I found Paul Junkroski, who was a high school sophomore sitting in the left field upper deck when the ball was hit.

“He hit the ball, and immediately you could see that there was no doubt, this was going to be a home run,” said Junkroski, by then a retired school teacher living in the Chicago area. “And then, suddenly, it dawns to all of us in the stands there that this ball’s going to come into the upper deck. It’s just coming up and up and up.14

“Then … we realized it’s not even coming into the upper deck, it’s going over.”15

The Chicago Tribune trumpeted Dave Nicholson’s feat. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Five decades after the event, he recalled it vividly. “As it disappeared above us, over the roof [that’s] when we heard a noise. Everybody sitting there heard something—something fell.”16

Junkroski worked as an usher at the ballpark that year. “That was an old wooden roof in that stadium. A lot of people didn’t realize that,” he told me. “There were always people up there—electricians or somebody who worked there.” The roof was 75-feet high. The ballpark, built in 1910, was torn down in 1991.17

Nearly two years after first calling him, I found both Nicholson and the ball outside Benton, Illinois.

He recalled that night. “When I hit the ball really good, I never watched them,” he said. But “I knew I really hit it good. There was always speculation it hit on the roof, over the roof, whatever—it got over the roof someway because the kid picked it up in the park across the street.” After he hit his famous home run that night, he told a reporter he was unsure whether it was the furthest one he had ever hit—there were a couple that he had hit in spring training, Nicholson explained, that might have gone even further.18,19

Nicholson hit three home runs that night during a doubleheader sweep of the then-Kansas City Athletics, which vaulted the White Sox temporarily into a first-place tie with the Cleveland Indians. His two home runs in the first game—including his moon shot—were off Moe Drabowsky, whom the newspaper the next morning noted “was once a Cub.”20

Entering the game, Nicholson had been scuffling, batting just .209, and up until that day had only two extra-base hits in 43 at-bats. He would be traded after the 1965 season.21

“I just didn’t hit enough,” he said, looking back. His best year—1963—was the “only decent year I had.”22

“We had a pretty good year, we finished second,” said Nicholson. “The only bad thing is, I struck out so much.”23

After not talking to Nicholson for several months— he was sick and not interested in talking anymore, he said—I wrote him a get-well card during the summer of 2017.

Out of the blue, he called. Still puzzled over what I wanted, he invited me down. The White Sox, perhaps sensing my sudden optimism, completed a sweep that day of the Houston Astros, who would go on to win the World Series. As I headed off to Illinois, my wife sent me a text: “There is still a 10 year old boy inside my guy, and a 24 year old baseball star inside that boy’s ‘guy’. Go find them both and introduce them to each other.”

It took me 23 hours to get there, and we had a four-hour visit.

It was the first day of September, and the White Sox were firmly in last place. Three days before, Nicholson had turned 78. I was 63. The red mailbox in front of his home read N-I-C-H-O-L-S-O-N.24

He was 182 pounds—frail, but feeling better. He nodded to the small lake outside his living room window, describing how winded he got walking up the hill from the boat dock. “This getting older is not the ‘Golden Years,’” he lamented.25

But just that day, Nicholson said, he had aut0graphed some baseball cards a collector had sent. Oddly, the requests for autographs still come, and he sometimes grows tired of driving to the post office after signing them to mail them back. The autograph requests, he said, “come from everywhere. I signed a bunch [a] couple months ago from Europe, from—what the heck was it—the Ukraine, or something like that.”26

The interest is hard to explain. Yet people do remember.

In March 2016, with Nicholson fighting an assortment of health problems and cursing his doctors, a young White Sox slugger with unfulfilled potential launched a mammoth home run in a spring training game. “Wow! That was some shot by Avi [Garcia]!” wrote one fan on a White Sox website. “It was Dave Nicholsonish.”27

In Benton, Nicholson lives in relative obscurity.

At a museum in the old jail near the city’s downtown, Bill Owens recited the names of the famous and near-famous who were born near Benton: John Malkovich, the actor, was a Benton-area native, as was Gene Rayburn, the TV gameshow host. And George Harrison, the quiet Beatle, visited his sister in Benton before the band’s first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show.

And Dave Nicholson?

“Does he live here in Benton?” Owens asked, pausing to consider the name. “Dave Nicholson—I’ve never heard of him, and I’m a baseball historian.”28

A week after my visit with Nicholson, the reference librarian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, put an even bigger dent into my favorite player.

I had asked her about Nicholson’s mammoth home run in 1964. “As for the home run,” Cassidy Lent emailed back. She pointed me to a Baseball Almanac article that listed the home run “among the other great exaggerations in the history of tape measure home runs” and said the alleged 573-foot blast had been calculated by “White Sox mathematicians.” The article concluded:

“These unidentified individuals based their calculations on the assumption that the ball traveled completely over the left-center field roof. [However], subsequent investigation indicated that the ball landed on the back of the roof before bouncing into the night.”29

Ouch.

The ball Nicholson hit that night—now yellowed and ancient-looking—sat in a small case in a bedroom at his home. On the ball, there are these words: “May 6 1964 over the roof White Sox Park 500+.” One of his favorite old gloves is on a nearby shelf. And so is the ball that the Minnesota Twins’ star, Harmon Killebrew, gave to the White Sox slugger when Nicholson broke Killebrew’s single-season record of 142 strike-outs. Killebrew had just himself set the record the year before, in 1962. “From one champ to another—Congratulations,” Killebrew wrote on it.30

There was one other baseball, and a story I had never heard before. Holding a ball with a partially torn off cover, Nicholson said this one had bounced off a car bumper in a parking lot after he hit the ball more than 500 feet. I asked him if he had ever seen The Natural, the 1980s movie where the fictitious Roy Hobbs in one scene literally hits the cover off the ball. “Phony as phony can get,” Nicholson said, laughing at the movie moment he, too, had seen. “But I liked it.”31

Five decades later, it was obvious that striking out 175 times in one season still stung Nicholson. Never mind that a lot of players had since broken his record. Mark Reynolds holds the current record—he struck out 223 times in 2009. Nicholson is now tied at No. 85 on the single-season strikeout list. “He’s got me by 50,” strikeouts, Nicholson said of Reynolds.32,33

Jeannie Nicholson, who was mostly quiet that day in Benton, suddenly began talking of how the sports reporters covering the White Sox seemed to rub in Nicholson’s strikeout problems. “That [was] kind of aggravating that they really harped on that—not that much attention to all the home runs he hit.”34

“They beat it to death,” Nicholson added. “Every damn article that was written about me, mentioned that.”35

In a hallway near the front door later that day, Nicholson moved on to happier memories. He paused by a picture of him in his White Sox pinstripes. He was young, with muscled biceps. His arms were extended, and he was swinging away. He even went into detail about his bat, a Louisville Slugger, Model N26.

“People said I looked a little like Mickey Mantle.”36

Right after my visit with Nicholson, Jim Landis died. He was 83, and had played mostly center field for the White Sox while Nicholson, for a couple of years at least, was next to him in left field. But Landis, who played on the White Sox World Series team in 1959, was much better known. Landis’s death was another sign that, one-by-one, his teammates were disappearing.37

The point of it all, of course, was mortality. Nicholson had emerged from a rough couple of years.

The worst stretch may have been March and April 2016. When I called in late March, it was Jeannie who answered, and she spoke to me for the longest she had ever talked. Her husband had been in the hospital three times in the past two months, she reported. The next day, she said, she planned to bring him home from his most recent stay.38

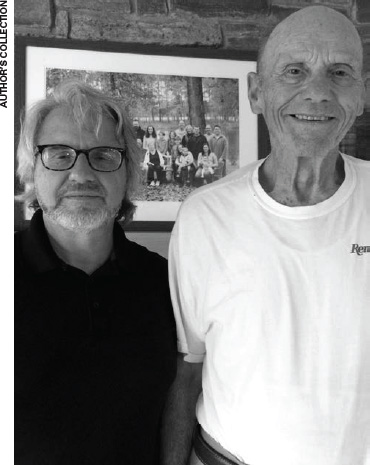

Dave Nicholson, right, and the author in September 2017. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The worry tumbled out of her. She was 15 when she met Nicholson, and married him at 19. Now she herself was 75.39

He was better, she said, but “he’s bored to death.”40

Opening Day for the White Sox that year was on April 4—a Monday—and I found myself briefly talking to a slightly upbeat Nicholson. The White Sox beat the A’s, 4—3, behind their then-ace Chris Sale, who struck out eight.41

“I haven’t even paid any attention,” he said when I asked him about Opening Day.42

Charlie Philpott, Nicholson’s grandson, has in many respects been the keeper of his grandfather’s flame. A longtime baseball fan himself, Philpott said his grandfather made him appreciate what may have been baseball’s golden age. Today’s athletes seem like celebrities who are “almost removed from society,” he said. In Nicholson’s time, the players “were regular everyday people and also somehow super human at the same time.”43

Though Nicholson had more recently opened up about his career, Philpott added, he did not seem too eager before that. “I’ve gotten the impression [the strikeout record] was maybe part of his reticence,” Philpott said. “[Maybe he] felt he didn’t have as good a career as he thought he should have.”44

During my sophomore year in high school, Nicholson’s career sputtered to a close with the Omaha Royals, a minor league team. His last year in the majors was 1967; he played in just 10 games for the Atlanta Braves. He struck out nine times in 25 at-bats. He had found a glimmer of hope in 1968, hitting 34 home runs for the minor league Richmond Braves. But he struck out 199 times.45

After his playing days ended, Nicholson owned a sporting goods store in suburban Chicago.46

With college and career in front of me, I lost track of him.

In the ensuing years I found new baseball heroes— White Sox sluggers like Dick Allen, Carlos May, Ron Kittle, and Frank Thomas. But it was never the same; the moment had come and gone. Even when the White Sox won the World Series in 2005, ending nearly a century of disappointment, I was happy but detached.

Fifty years after Nicholson played, I lived in a world where cynicism came easy. I covered the Minnesota Twins’ quest to use a boatload of taxpayer money to build a new ballpark—even though the team’s owners were incredibly affluent. On the night the public subsidy package passed the state legislature, I watched as a sports columnist from my own newspaper sat with team officials and cheered on the vote. What I was writing about then, I remember telling myself, had nothing to do with the actual game.

Nicholson believed he played at a special time. He hit his last home run, he claimed, off Sandy Koufax, the Hall of Fame pitcher and baseball legend.47 He faced, among many others, Bob Gibson, the St. Louis Cardinals’ intimidating right-hander and two-time Cy Young Award winner who is now also a Hall of Famer. He saw Ted Williams take the last swing of his major league career.48

I had not lived in Chicago since the early 1970s, but I did go to a White Sox game while visiting a couple of years ago.

The White Sox’ old stadium had been gone for a quarter century. But the spot that marks the stadium’s old home plate is in a nearby parking lot. Standing there, looking north toward a hazy Chicago skyline, I could still picture how far the ball traveled on that Tuesday night in 1964 before it reached Murillo.

The White Sox lost that day, 10—2—but that was not the worst of it. At about the time of my Chicago visit, the website Sportsbreak came out with a list of the 15 longest home runs in American and National League history. I had never heard of the website, but sports fans—me included—love lists. So, I bit, and clicked on it. Nicholson’s name was nowhere to be found.49,50

When I found John Nicholson, Dave’s younger brother by nearly three years, he still lived in St. Louis where the family grew up on the city’s west side. Yogi Berra, the famed Yankees catcher, had grown up nearby. Dave had the baseball talent, he said. “I was no good,” said John. Even as a teenager, Dave was hitting long home runs, and drawing major league scouts. “He was like my dad, [and] my dad was a very strong [guy]” said John.51

John retired after more than 40 years in the machine trades. Though he lived for a while in Chicago, and attended White Sox games, he couldn’t recall ever seeing his brother hit a major league home run in person.52

Now it hurt to see his brother in pain. “He looks [like] a shadow of what he used to be.”53

So “I say a little prayer every night.”54

As my visit with Nicholson came to an end, Jeannie took a picture of the two of us in front of the fireplace. Though I did not notice at first, Nicholson was smiling.

I thought of asking Nicholson for his autograph. As a kid, I never had it. But I never did ask, thinking it would cheapen the moment. I had found a long-ago hero who was now an old man, but who still tugged at something inside of me. We had, for now, both survived a strange journey from the past to the present. For me, that was enough.

MIKE KASZUBA is a retired newspaper reporter, and spent 35 years at the Minneapolis Star Tribune. He covered local and state government, as well as sports business issues, and was the lead reporter covering the public subsidy packages used to build stadiums for the Minnesota Twins, Minnesota Vikings, and the University of Minnesota football program. He is a native of the Chicago area, currently lives in Florida and has been a SABR member since 2020. He can be reached at michaeljkaszuba@gmail.com.

Notes

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, January 8, 2016.

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, February 10, 2016.

- Jeannie Nicholson, telephone interview, November 29, 2016.

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, October 27, 2015.

- Baseball-Reference.com, baseball box scores, October 1, 1967.

- It should be noted that there’s no evidence of this home run. Gary Peters, telephone interview, September 21, 2016.

- Gary Peters, telephone interview, September 21, 2016.

- Strat-O-Matic Baseball, Dave Nicholson, 1963 card.

- Operation White Sox, team yearbook, 1964, 123.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Paul Junkroski, telephone interview, January 27, 2016.

- Paul Junkroski, telephone interview, January 27, 2016.

- Paul Junkroski, telephone interview, January 27, 2016.

- Paul Junkroski, telephone interview, January 27, 2016.

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, November 5, 2015.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Edward Prell, “Slugging Sox Win 2; Cubs Beat Giants,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1964, 3—1.

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, November 5, 2015.

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, November 5, 2015.

- Baseball-Reference.com, baseball standings, September 1, 2017.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- SBNation.com, https://sbnation.com/users/grinnellsteve/search/2?q=avi+garcia+and+march+9,+2016&type=comment.

- Bill Owens, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Cassidy Lent, reference librarian, Baseball Hall of Fame, September 7, 2017.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Baseball-Reference.com, Single-Season Strikeout Leaders.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Jeannie Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Baseball-Reference.com, Jim Landis biography, October 7, 2017.

- Jeannie Nicholson, telephone interview, March 25, 2016.

- Jeannie Nicholson, telephone interview, February 13, 2017.

- Jeannie Nicholson, telephone interview, March 25, 2016.

- Baseball-Reference.com, baseball box scores, April 4, 2016.

- Dave Nicholson, telephone interview, April 4, 2016.

- Charlie Philpoa, telephone interview, October 6, 2017.

- Charlie Philpoa, telephone interview, October 6, 2017.

- Baseball-Reference.com, Dave Nicholson, biography.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- His last home run was off of Larry Jackson.

- Dave Nicholson, in-person interview, September 1, 2017.

- Baseball-Reference.com, baseball box scores, August 7, 2016.

- Sportsbreak.com, https://sportsbreak.com/mlb/the-15-longest-home-runs-ever-hit.

- John Nicholson, telephone interview, September 6, 2017.

- John Nicholson, telephone interview, September 6, 2017.

- John Nicholson, telephone interview, September 6, 2017.

- John Nicholson, telephone interview, September 6, 2017.