Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers: 1946–60

This article was written by Herm Krabbenhoft

This article was published in Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

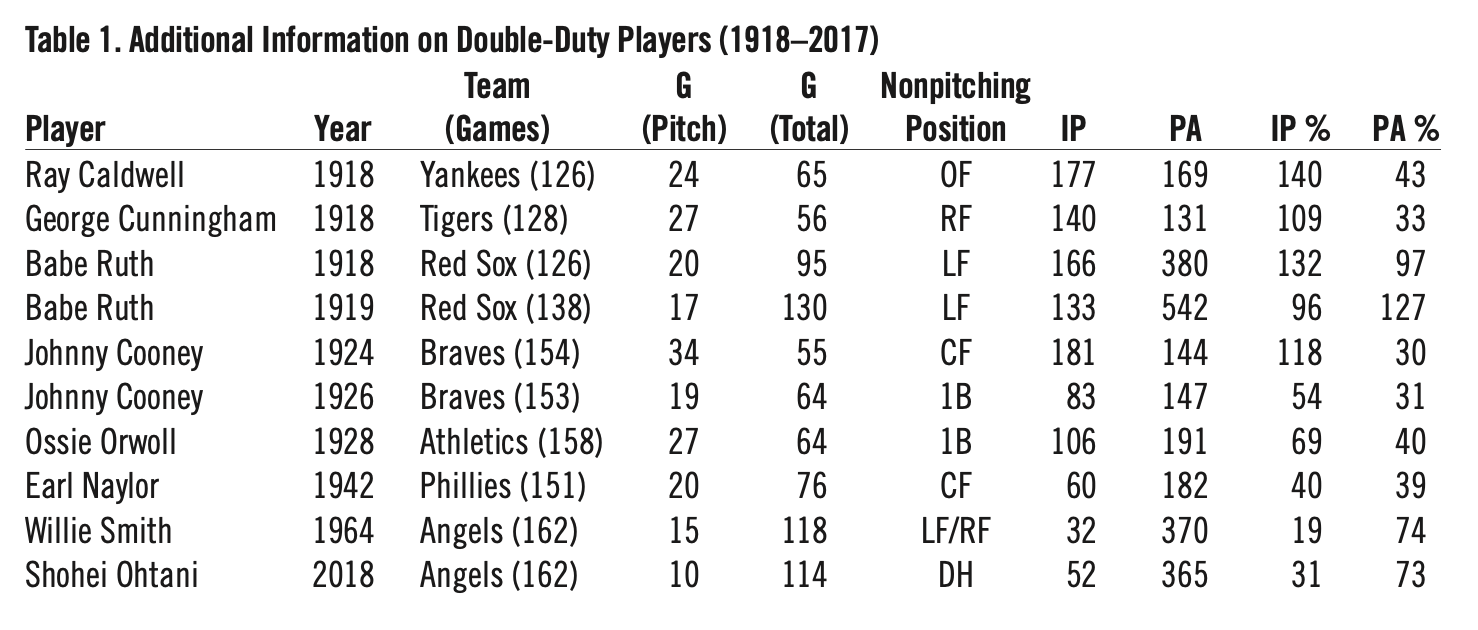

A few days after Shohei Ohtani made his major league debut on March 29, 2018, Jay Jaffe wrote, “Ohtani is doing things that haven’t been done at the major league level in nearly a century. … and not since 1919 has a player served as both a starting pitcher and a position player with any kind of regularity.”1 Jaffe also included a chart to illustrate his point. The salient aspects of Jaffe’s chart plus some additional information (such as Ohtani’s full-season statistics for 2018) are shown in Table 1:

Table 1. Additional Information on Double-Duty Players (1918-2017)

The six left-most columns are taken as-is from Jaffe’s chart with the number of games played per team added (in parentheses). The next two columns — Innings Pitched (IP) and Plate Appearances (PA) — are presented to provide additional perspective. The final two columns (IP % and PA %) show to what extent the player was a full-time performer as a pitcher and as a batter, according to the official rules of Major League Baseball.2 IP % and PA % are defined as follows:

- IP % = [Innings Pitched (Player) / Games Played (Team)] x 100

- PA % = [Plate Appearances (Player)) / 3.1 x Games Played (Team)] x 100

IP % is simply a player’s Innings Pitched divided by the number of games his team played. Similarly, PA % is a player’s plate appearances divided by the product of 3.1 times the number of games his team played. Thus, for a pitcher to be considered a full-time performer — i.e., to qualify for the earned run average title — he must have accumulated at least one inning pitched per game played by his team. Therefore his IP % must be equal to or greater than 100. Similarly, for a batter to be considered a full-time performer — i.e., to qualify for the batting average championship — he must have accumulated at least 3.1 plate appearances per game played by his team. His PA % must be equal to or greater than 100. For example, in 1918, Ray Caldwell amassed 177 innings pitched, which are 51 IP greater than the 126 IP needed to qualify for the ERA crown (i.e., IP % = 140 %); and he accumulated a total of 169 plate appearances, which are 222 PA fewer than the 391 PA needed to qualify for the batting crown (i.e., PA % = 43 %).

NOTE: Appendix One, available below, presents a chronological summary of the official qualifications required for the earned run average and batting average crowns for the 1946–60 period.

Jaffe’s criteria for inclusion in his list of double-duty players are that the player “pitched at least 15 times in a season and played a(nother) position …at least 15 times as well.” Thus, for the 100-year period from 1918 through 2017, Jaffe identified seven players as double-duty major-league players — Ray Caldwell, George Cunningham, Babe Ruth, Johnny Cooney, Ossie Orwoll, Earl Naylor, and Willie Smith. However, as shown in the four right-most columns of Table 1, none of these players — including Babe Ruth — were simultaneously truly full-time pitchers and truly full-time batters. There were only four instances where a pitcher achieved at least the minimum number of innings pitched — Caldwell, Cunningham, Ruth (1918), and Cooney (1924); and there was only one occurrence where a pitcher accumulated at least the minimum number of plate appearances — Ruth (1919). Table 1 shows that going back to 1918 there has not been even one player in the major leagues who was both a full-time pitcher and a full-time batter in the same season. But what about the minor leagues? In this article I present the results of my research to address this question.

RESEARCH PROCEDURE

As shown in Table 1, no player — not even Babe Ruth — was technically a full-time pitcher and a full-time batter in the same season. In order to not be so restrictive, I have chosen to moderate the qualifications and have reduced the official requirements by ten percent. Thus, to be regarded as a full-time pitcher for purposes of this article, the player had to have amassed at least 0.9 IP per game played by his team (IP % ≥ 90). Likewise, to be regarded as a full-time batter, the player had to have accumulated at least 2.8 PA per game played by his team (PA % ≥ 90). I have chosen to research 1946 through 1960. The 1946 season was the first after the conclusion of World War II., while the 1960 season was the last before the American League expanded in 1961. Significantly, the 1946–60 period includes the so-called “Golden Age” of minor league baseball (1946–51).3 All teams in all leagues from classifications AAA through D were included. Using the annual Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published by The Sporting News) as the source for the statistics, I first ascertained which players qualified as full-time pitchers. Then I ascertained which of them on that list also qualified as full-time batters.

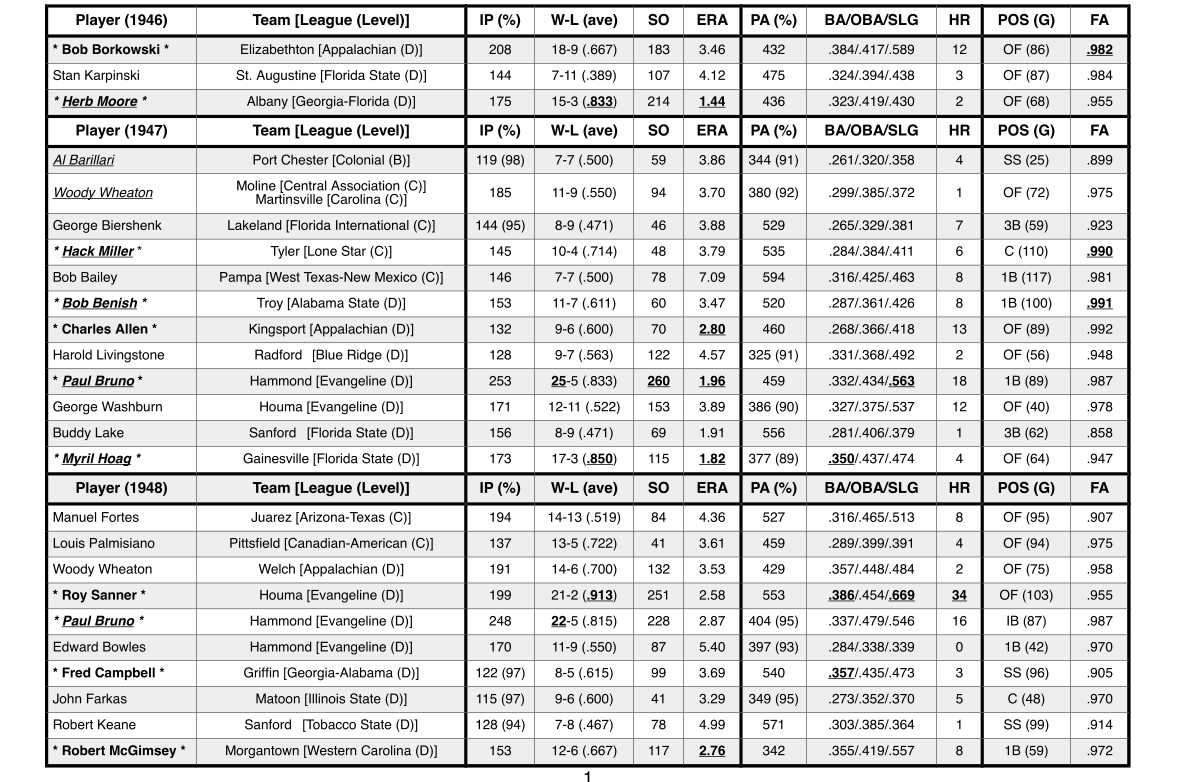

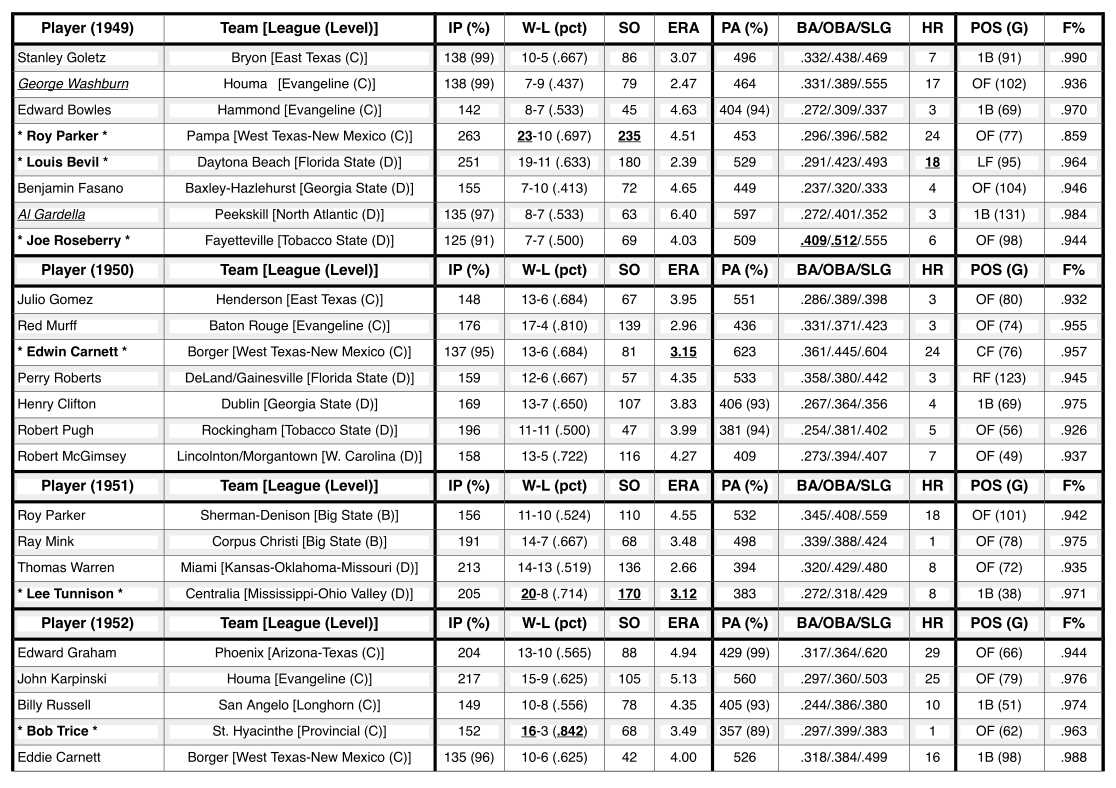

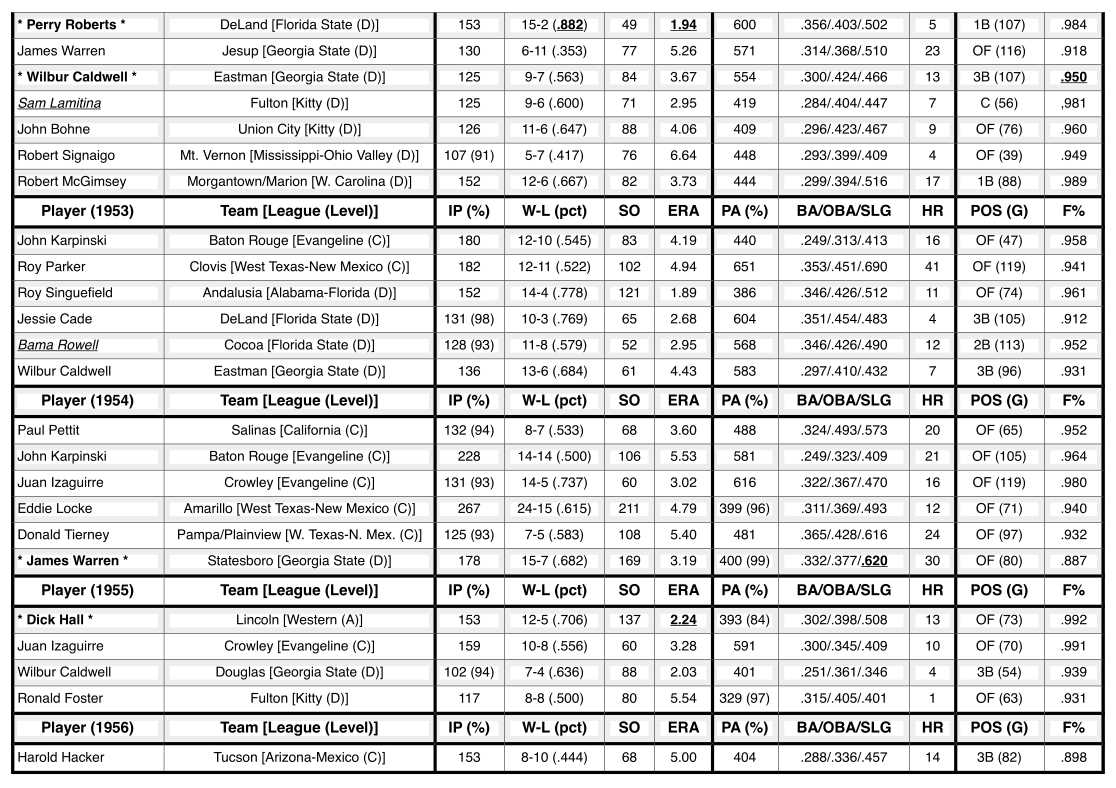

Table 2. Selected Statistics for Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers (1946-1960)

(Click images to enlarge)

NOTES:

-

When a player’s name is shown in boldface and bracketed with *asterisks* it indicates that the player led his league in one or more of the statistical categories shown; the league-leading number is shown in underscored boldface.

-

When a player’s name is shown in underscored italics it indicates that the player was his team’s full-season player-manager.

-

For the IP (%) and PA (%) columns, the former gives the Innings Pitched by the player and the latter gives the number of Plate Appearances the player had. If the player had fewer innings pitched than 100% of the games played by his team(s), then that percentage is shown (in parentheses); if the player’s number of innings pitched is equal to or greater than the number of games played by his team(s) (e.g., 100% or 123%), then the percentage is not shown. Likewise for the PA (%) column — if the player’s number of plate appearances is less than 3.1 times the number of games played by his team(s), then the percentage of plate appearances is shown (in parentheses); if the player’s number of plate appearances is equal to or greater than 3.1 times the number of games played by his team(s) (e.g., 100% or 145%), then the percentage is not shown.

-

Plate Appearances (PA) were calculated by adding the player’s number of At Bats (AB), Bases on Balls (BB), Hit by Pitched balls (HP), and Sacrifice Hits (SH) as given in the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published annually by The Sporting News).

-

The entries in the columns W–L (pct), SO, ERA, HR, POS (G), and F% are taken directly from the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published annually by The Sporting News); likewise the BA entry.

-

The entry for OBA was calculated as follows: [H + BB + HP] / [AB + BB + HP]; the values for H, BB, HP, and AB were taken directly from the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published annually by The Sporting News).

-

The entry for SLG was calculated as follows: TB / AB; the values for TB and AB were taken directly from the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published annually by The Sporting News).

-

The POS (G) column provides the principal fielding position, POS, of the player; the games player played at that position are given (in parentheses) and were taken directly from the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published annually by The Sporting News).

-

The F% column provides the fielding percentage the player accomplished in his principal fielding position; the F% was taken directly from the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published annually by The Sporting News).

RESULTS

According to my research, during the 1946–60 seasons there were 59 players who were day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers for at least one campaign in the minor leagues. All together, there were 75 day-in/day-out double-duty player-seasons; see Table 2 for pertinent information for each of these player-seasons. The main focus of this article is on those day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers who were top performers as either pitchers or hitters — and a few were top performers both on the slab and at the plate. Six topics are covered:

- Top Pitchers

- Top Batters

- A Composite All-Star Lineup

- Playing-Managers (i.e., Triple-Duty Diamondeers)

- Players with Multiple Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty seasons

- Minor League Double-Duty Players Who Played in the Major Leagues

1. Top Pitchers Among Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers

There were nine day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers who compiled the lowest ERA in their respective leagues — Herb Moore (1946), Charles Allen (1947), Paul Bruno (1947), Myril Hoag (1947), Robert McGimsey (1948), Eddie Carnett (1950), Lee Tunnison (1951), Perry Roberts (1952), and Dick Hall (1955). All but one of the players achieved his ERA crown in a class D or C minor league. The lone exception was Dick Hall of the 1955 Lincoln Chiefs of the Class A Western League. Hall did not technically achieve full-time batter status — his PA % was “only” 84 (instead of the specified 90 %; he had 393 PA of the required 468 PA). But Hall also spent time with Pittsburgh in the National League — 21 games with 47 PA. Including those 47 PA affords a composite total of 440 PA, which yields a PA % of 94.

Two of the double-duty diamondeers who claimed ERA thrones also led in wins and strikeouts. Both Paul Bruno and Lee Tunnison emerged with the most wins (25 and 20, respectively) and the most strikeouts (260 and 170, respectively) in their leagues, thereby earning the pitching Triple Crown. Bruno also turned in excellent stats as a batter, with a .332/.434/.563 slash line and 18 homers. He finished fourth in batting average (.332 vs. .351), second in on base percentage (.434 vs. .459), and first in slugging average (.563); he also came in second in homers (18 vs. 22). Tunnison turned in a more-than-adequate batting record, batting .272 with eight homers while playing first base and the outfield.

2. Top Batters Among Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers

There were four day-in-day-out double-duty diamondeers who compiled the highest batting average in their respective leagues. Each of the four batting champions — Myril Hoag (1947), Roy Sanner (1948), Fred Campbell (1948), and Joe Roseberry (1949) — played for a Class D minor league. Hoag’s PA % (89) was just a notch below the specified 90 %, but according to the unofficial rules in effect prior to 1950 — i.e., appearance in at least 100 games — Hoag was the official batting champ, having played in 102 of Gainesville’s 137 games. Moreover, adding 6 imaginary hitless at bats to Hoag’s actual 377 PA (thereby giving him the requisite minimum 383 PA and affording him a 90 PA %) reduced his batting average to a hypothetical .343, a value still far greater than runner-up Al Pirtle’s .316 batting average.

Only two day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers topped their circuits in home runs — Roy Sanner of the 1948 Houma Indians of the Class D Evangeline League clouted 34 round-trippers, and Lou Bevil of the 1949 Daytona Beach Islanders of the Class D Florida State League smacked 18. Three double-duty men emerged as RBI leaders in their leagues — Roy Sanner (126 in 1948), Fred Campbell (105 in 1948), and Bama Rowell (127 in 1953). Thus, in 1948 Sanner won the prestigious Triple Crown in batting. While Sanner’s record as a batsman was outstanding, his pitching was superb, leading the league in winning average (.913) thanks to a 21–2 record, and only one win behind the league leader’s 22. Similarly, his 2.58 ERA was runner-up to the league leader’s 2.37, and his 251 strikeouts were the second-most to 259.4 Thus, Sanner finished a close second in all three pitching Triple Crown categories.

Only two day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers emerged as the stolen base leader in their circuits — Wilbur Caldwell (58 in the Georgia State League) and John Bohna (44 in the Kitty League), each in 1952.

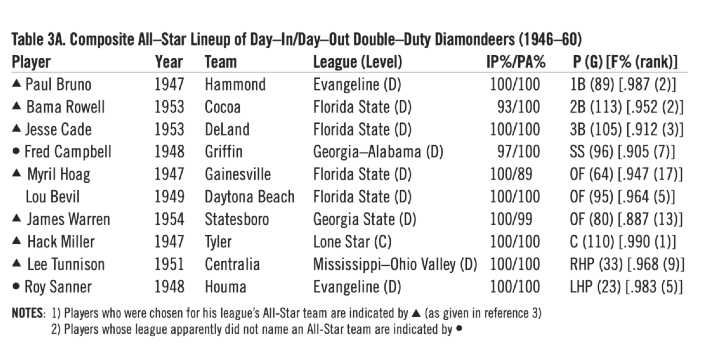

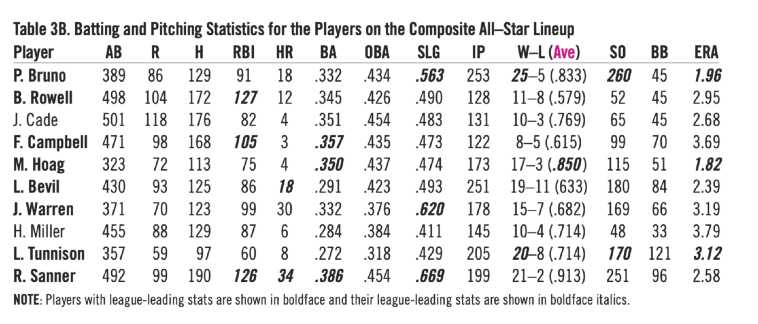

3. A Composite All-Star Lineup of Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers

Taking into consideration the single-season performances of all 59 players who were Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers during the 1946–60 period, Table 3A presents a composite All-Star lineup (irrespective of year or league). Table 3B provides the batting and pitching statistics for each of the All-Stars.

Table 3A. Composite All-Star Lineup of Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers (1946–60)

Table 3B. Batting and Pitching Statistics for the Players on the Composite All-Star Lineup

Six of the Table 3A All-Stars were selected for their league’s All-Star team, as given in The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Second Edition, 1997) — Paul Bruno (first base), Bama Rowell (second base), Jesse Cade (third base), Myril Hoag (outfield), James Warren (outfield), and Lee Tunnison (pitcher). With regard to the other Table 3A players, here is some pertinent information:

- Roy Sanner — The Evangeline League apparently did not name an All-Star team for the 1948 season. However, it seems reasonable to speculate that, if there had been a 1948 Evangeline League All-Star team, Roy Sanner would have been included, at least as an outfielder, and perhaps also as a pitcher.

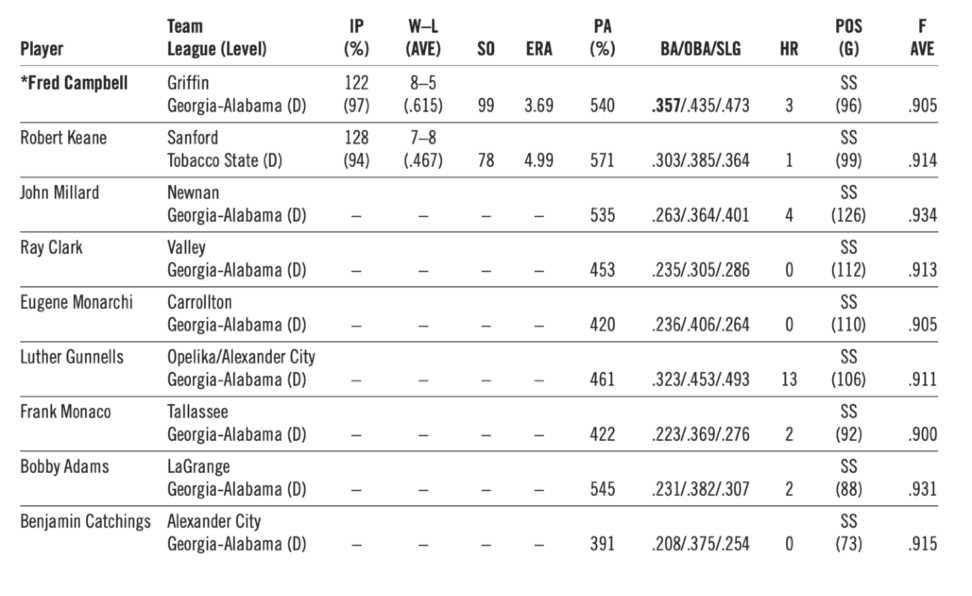

- Fred Campbell — The Georgia-Alabama League did not name an All-Star team for the 1948 season, but Fred Campbell could have been chosen as the loop’s All-Star shortstop. For comparison, Appendix Two provides the relevant statistics for the principal shortstops of the 1948 Georgia-Alabama League. The Tobacco State League did choose an All-Star team in 1948, naming double-duty diamondeer Robert Keane, but my preference for inclusion in Table 3A is Fred Campbell.

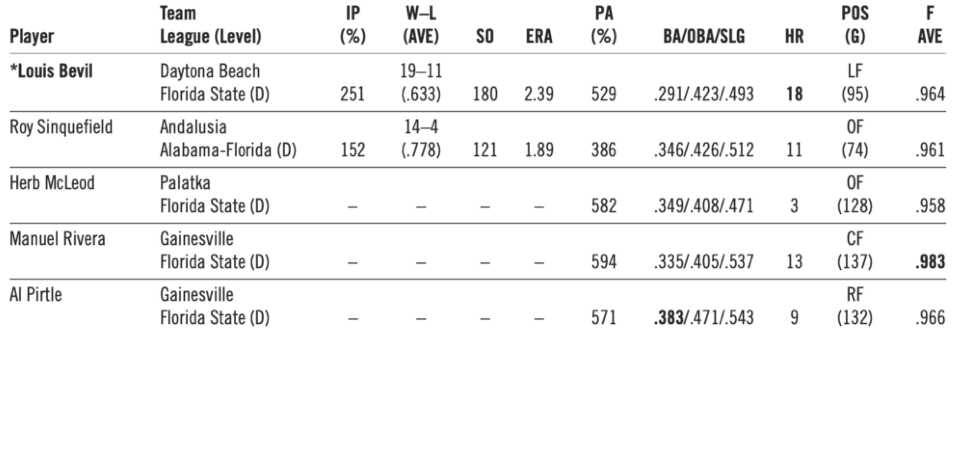

- Lou Bevil — Appendix Two presents the batting statistics for each of the three players selected as outfielders for the 1949 Florida State League All-Star team — Herb McLeod, Manuel Rivera, and Al Pirtle. However, since none of them pitched in any games, none of them were eligible for the composite All-Star lineup. While Roy Sinquefield (Andalusia — Alabama-Florida League, 1953) was deservedly chosen as an All-Star for his league, Lou Bevil is my preference for the Table 3A composite All-Star lineup.

- Hack Miller — The 1947 Lone Star League’s All-Star catcher was Joe Kracher of the Kilgore Drillers; his batting slash line (.333/.424/.505) was quite a bit better than Miller’s .284/.384/.411. However, since Kracher did not pitch in any games, he was not eligible for the composite day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeer All-Star lineup. Miller’s batting and pitching records were superior to those achieved by John Farkas (1948) and Sam Lamitina (1952), the only other day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers whose principal non-pitching position was catcher.

As can be seen in Table 3B, eight of the ten players comprising the composite All-Star lineup were league leaders in various batting and pitching categories — RBIs (3), home runs (2), batting average (3), slugging average (3), wins (2), winning average (2), strikeouts (2), and earned run average (3). Finally, note that Bama Rowell was also chosen as his league’s All-Star manager.

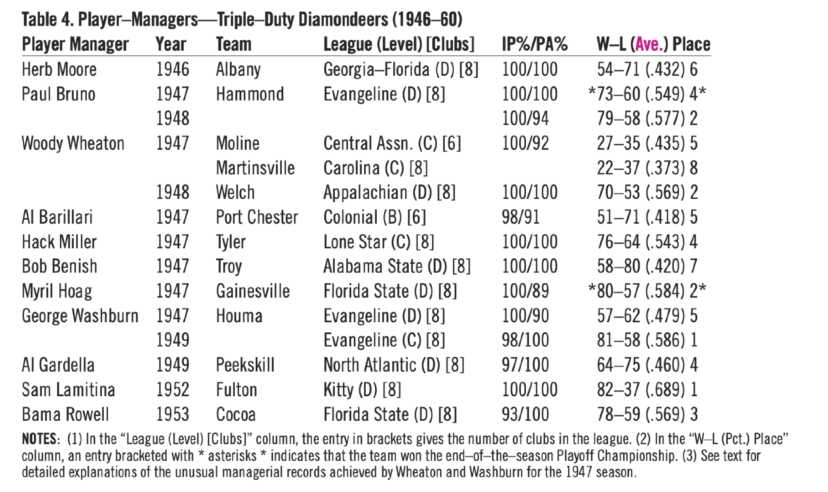

4. Player-Managers — Triple-Duty Diamondeers

Table 4 presents a list of day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers who were also full-time player-managers. Each of them can be justifiably regarded as a Triple-Duty Diamondeer! Two of them guided their teams to their league’s pennant — George Washburn (1949 Evangeline League), Bennie Warren (1951 Sooner State League), and Sam Lamitina (1952 Kitty League). Two of the Triple-Duty Diamondeers piloted their clubs to their league championship in the end-of-the-season playoffs — Paul Bruno (1947 Evangeline League) and Myril Hoag (1947 Florida State League). Bruno was not meant to be Hammond’s manager for 1947; Babe Benning was. As it turned out, however, Benning “resigned from the pilot’s job at Hammond just before the season opened.”5 Bruno entered the picture at this point and became Hammond’s manager for all of 1947.

Table 4. Player-Managers — Triple-Duty Diamondeers (1946–60)

Only three of the Table 4 player-managers were repeat day-in/day-out triple-duty diamondeers — Paul Bruno and Woody Wheaton in 1947 and 1948, George Washburn in 1947 and 1949.

Wheaton and Washburn each had unusual triple-duty seasons in 1947:

- Wheaton began the 1947 season with the Moline Athletics (Philadelphia’s farm club in the Class C Central Association). With him as manager, the team compiled a 27-35 W-L record, good for fifth in the standings. On July 11, he joined the Martinsville Athletics (Philadelphia’s farm club in the Class C Carolina League) when Martinsville’s W-L record was 31-51 and they were in eighth (last) place. For the remainder of the season, Wheaton piloted them with a 22-37 W-L record; overall, Martinsville finished with a 53-88 W-L record.

- Washburn began the 1947 season with New Orleans (AA Southern Association), where Fred Walters was the manager. Two weeks after playing in his one-and-only game for the Pelicans (a complete-game 8-5 triumph over Memphis on April 21), his contract was purchased by Houma to replace player-manager Copeland Goss, who departed with a 6-14 W-L record. Washburn made his Houma debut as player-manager on May 8. Under his guidance, the Berries went 57-62, thereby giving Houma a final W-L record of 63-76, which placed them fifth in the standings.

5. Players with Multiple Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Seasons

Close inspection of Table 2 reveals that twelve players were day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers for more than one season. Eight players met our criteria for two seasons:

- Paul Bruno (1947, 1948)

- Woody Wheaton (1947, 1948)

- George Washburn (1947, 1949)

- Edward Bowles (1948, 1949)

- Eddie Carnett (1950, 1952)

- Perry Roberts (1950, 1952)

- James Warren (1952, 1954)

- Juan Izaguirre (1954, 1955))

Four players were three-time day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers:

- Robert McGimsey (1948, 1950, and 1952)

- Roy Parker (1949, 1951, 1953)

- Wilbur Caldwell (1952, 1953, 1955)

- John Karpinski (1952, 1953, 1954)

There were no players with four or more day-in/day-out double-duty seasons during the 1946–60 period. An interesting item which may be gleaned from Table 2 is that five of these dozen players played in the Evangeline League — Bruno, Washburn, Bowles, Karpinski, and Izaguirre.

6. Minor League Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers Who Played in the Major Leagues

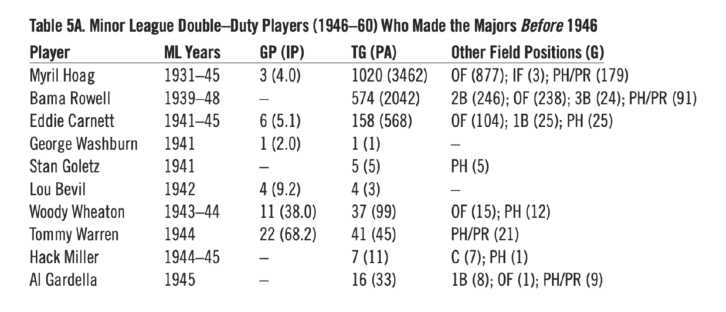

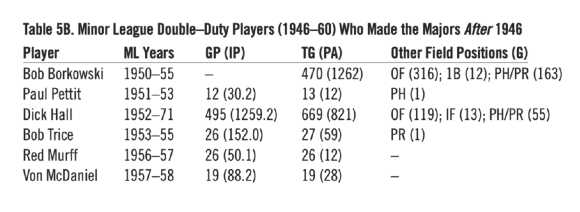

As previously noted, no day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers have played in the major leagues since 1919. But since we have identified 59 in the minor leagues, it follows that we consider two questions: (1) “Which, if any, of the 59 minor league day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers progressed to the major leagues as pitcher or as a field-position player?” (2) “How did they perform when they got there?” As it turns out, 16 of the minor league double-duty diamondeers from the 1946–60 period did make the Show. However, there are two distinct groups of players within the 16, those who made their major league debut before 1946, and those after 1946. Tables 5A and 5B provide pertinent information for these two groups.

Table 5A. Minor League Double-Duty Players (1946-60) Who Made the Majors Before 1946

Table 5A reveals that most of these players had their big-league careers during World War II. None of the six players who toed the rubber accumulated a career total of even 77 innings pitched (the equivalent of a half-season for a pitcher). Only two of the ten players accumulated more than 1,000 big-league plate appearances — Myril Hoag and Bama Rowell.

Hoag (271/.328/.364) was in the bigs 13 of the 15 seasons from 1931 through 1945 (except 1933 and 1943), and after that he continued his professional baseball career in the minors. Interestingly, he was a teammate of Babe Ruth (1931, 1932, and 1934) and was on the New York Yankees World Series championship teams of 1932, 1936, 1937, and 1938. Rowell (.275/.316/.382) played six major-league seasons (1939–41 and 1946–48). Bennie Warren (.219/.313/.360) played for the Phillies (1939–42) and Giants (1946–47).

A Table 5A player with an exceptional (but brief) big league career (seven games) was Hack Miller. Beginning in perhaps the best way possible, Miller hit a home run in his first at bat — on April 23, 1944 (second game) off Cleveland’s Al Smith. He concluded his time in the bigs with the 1945 World Champion Detroit Tigers as a backup catcher (although he did not appear in any of the Fall Classic games).

The Table 5A player who came the closest to being a double-duty diamondeer in the majors was Woody Wheaton, who played two seasons (1943, 1944) for the Philadelphia Athletics. He appeared in 11 games on the mound (all in 1944) and came away with a 0-1 W-L record with an earned run average of 3.55. He was utilized as a relief pitcher except once, when he hurled a complete game against the St. Louis Browns on July 6, 1944, losing 5-0. Wheaton also played center field in 15 games — seven in 1943 and eight in 1944 — and was also employed as a pinch hitter in twelve games. For his entire major-league career he turned in a .191 batting average (17 hits in 89 at bats).

Tommy Warren, playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers for one season (1944), was the Table 5A player who appeared in the most games as a pitcher — 22. He compiled a W-L record of 1-4 with an ERA of 4.98. Warren’s only other major-league action was as a pinch hitter or pinch runner (21 games).

Turning now to Table 5B and the double-duty diamondeers with post-1946 major-league debuts, only one player accumulated more than 1000 plate appearances — Bob Borkowski. Borkowski had a single season as a minor league double-duty diamondeer, 1946, and zero mound appearances in the majors. Primarily an outfielder during his six seasons with the Cubs, Red Legs, and Dodgers, Borkowski put together a career slash line of .252/.298/.346 with 16 home runs.

Table 5B. Minor League Double-Duty Players (1946-60) Who Made the Majors After 1946

Among the Table 5B players, Dick Hall — who won the ERA crown as a double-duty diamondeer in the Western League in 1955 — carved out the most impressive record in the majors. While he debuted with the Pittsburgh Pirates as an outfielder (14 games in 1952, 102 in 1954), Hall switched his emphasis to the mound in 1955 and by 1957 had become exclusively a pitcher. After limited mound time with Pittsburgh (44 games with 23 starting assignments, 1955–59), Hall’s mound work accelerated with the Kansas City Athletics (29 games with 28 starts in 1960) and he flourished as a fireman with the Baltimore Orioles (1961–66, 1969–71) and Philadelphia Phillies (1967–68) — 79–49 W-L (.617) with an ERA of 2.92 and 69 saves. Hall was on the O’s World Series Championship teams of 1966 and 1970. With regard to Hall’s performance with the bat as a big leaguer, he manufactured a slash line of .210/.271/.259 with 4 homers.

The other four Table 5B players — Paul Pettit, Bob Trice, Red Murff, and Von McDaniel — had rather brief careers in the majors. The latter three at least gained the honor of appearing on a Topps baseball card.

Paul Pettit is perhaps most-remembered as the first recipient of a six-figure signing bonus in major-league history — $100,000 from the Pittsburgh Pirates on January 30, 1950. Unfortunately, Pettit encountered arm problems and lost the zip on his fastball. His career W-L record was 1-2 with a 7.34 ERA. Nonetheless, Pettit continued to try to make it in the minors for a few years (1953–56) and in 1954, with the Salinas Packers of the Class C California League, accomplished a day-in/day-out double-duty season with the following stats: batting .324/.488/.573 with 20 homers in 361 at bats (488 plate appearances); pitching numbers — 8-7 W-L (.533), 68 SO, 51 BB, 3.61 ERA in 132 innings pitched. Pettit’s .488 on base average and .573 slugging average each ranked second in the loop.

Bob Trice is remembered as being the first African American to play for the Philadelphia Athletics. He debuted on September 13, 1953, following a late-season call-up from Ottawa, the A’s Triple-A farm club in the International League. At Ottawa, Trice had netted the IL “Pitcher of the Year” with a sterling slab record — 21-10 W-L (.677) with a 3.10 ERA. The previous season, with St. Hyacinthe (the A’s farm club in the Class C Provincial League), Trice had put together his only double-duty campaign — 16-3 W-L (.842) with a 3.49 ERA in 152 innings from the pitcher’s box and a .297/.399/.383 slash line with 1 home run in 300 at bats (351 plate appearances) from the batter’s box. He led the league in wins (16) and winning average (.842). In his only full major-league season (1954) Trice turned in a 7-8 W-L (.467) with a 5.60 ERA in 119 innings pitched. But among all full-time pitchers in the AL, Trice compiled the highest batting average (.286), on base average (.348), slugging average (.429), and OPS (.776). For his career, Trice compiled a 9-9 record with a 5.80 ERA in 152 innings pitched. Trice appeared in one game as a pinch runner and produced a very solid .288/.351/.423 slash line with one homer in 52 at bats (59 plate appearances).

Red Murff was The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year in 1955, having turned in a superb 27-11 W-L ledger (.711) with a 1.99 ERA in 303 innings pitched for the Dallas Eagles, the New York Giants’ farm team in the AA Texas League; he was exclusively a pitcher. His only season as a day-in/day-out double-duty player was in 1950 with the Baton Rouge Red Sticks (Class C Evangeline League) He compiled .332/.371/.423 with 3 homers in 404 at bats (429 PA) as a bat swinger and 17-4 W-L (.810) with a 2.97 ERA as a ball slinger. As a major leaguer (exclusively as a pitcher) Murff ended up with a 2-2 W-L (.500) with a 4.65 ERA in 50.1 innings pitched for the Milwaukee Braves (1956 and 1957).

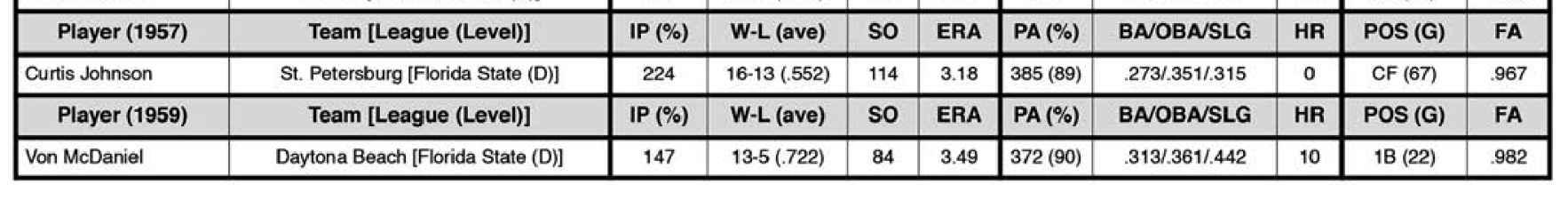

Von McDaniel began his major-league career with the St. Louis Cardinals right after graduating from high school. In his Cardinals debut (June 13, 1957) he relieved Herm Wehmeier and tossed four shutout innings of one-hit ball against the Phillies. In his next outing, against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, he again tossed four scoreless relief innings of one-hit ball, picking up his first victory in big leagues in the process. His next mound task was a starting assignment against the Dodgers at Busch Stadium in St. Louis; he finished with a two-hit, complete-game whitewash. McDaniels’s next game was another home-start, this time against Philadelphia. He extended his string of career-beginning scoreless innings to 19 when he kept the Phillies from crossing the plate in the first two frames.6 McDaniel was relieved after 7.1 innings, but was credited with the win. A little later in the season he tossed a one-hit masterpiece against the Pirates, facing just 28 batters. For the season he ended up with a 7-5 W-L ledger (.583) and a 3.22 ERA. However, he was winless in his last three starts and pounded harshly in his last 3.1 innings — 24 batters, 6 walks, 8 hits (including 2 homers), 7 runs (all earned).

That disastrous performance was a harbinger of the difficulty he would encounter in his next season. McDaniel’s 1958 season was bleak and short: after just two appearances — 2.0 innings, 16 batters, 5 walks, 5 hits, 3 runs (all earned) — he was sent down to the minors, thereby finishing his major league career less than a year after his debut. He kept at it in the minors and in 1959 produced his only day-in/day-out double-duty season. With the Daytona Beach Islanders (the Los Angeles Dodgers farm club in the Class D Florida State League) he produced a .313/.361/.442 slash line with 10 homers in 342 at bats (375 plate appearances) and a 13-5 W-L (.722) with a 3.49 ERA in 147 innings pitched. Significantly, he was selected for the Florida State League’s All-Star team as a utility player, having played first base (22 games), shortstop (19 games), and the outfield (16 games) in addition to pitching (20 games).

DISCUSSION

In transitioning from being an elite full-time pitcher (1915–17) to an elite full-time batsman (1920–31), Babe Ruth established an exemplary standard of performance for a day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeer during the 1918 and 1919 seasons, particularly from the batter’s box, as indicated by his league-leading stats in Table 6 (shown in bold).

Table 6. Babe Ruth’s Pitching and Batting Record for 1918 and 1919

|

Year |

IP |

W-L (%) |

SO |

BB |

ERA |

PA |

BA/OBA/SLG |

R |

HR |

RBI |

|

1918 |

166.1 |

13-7 (.650) |

40 |

49 |

2.22 |

382 |

.300/.411/.555 |

50 |

11 |

61 |

|

1919 |

133.1 |

9-5 (.643) |

30 |

58 |

2.97 |

543 |

.322/.456/.657 |

103 |

29 |

113 |

In the AL in 1918, Ruth’s W-L percentage and ERA ranked second and ninth, respectively; his corresponding rankings in 1919 were 10th and 22nd. (Note: The qualifier that I used is having an IP% ≥ 90 and a PA% ≥ 90, since in those times, there were no official rules about qualifying for the ERA or win percentage crowns. The unofficial rule was, as I understand it from Pete Palmer, 10 complete games.) Swinging the bat, the emerging Bambino topped the AL in slugging percentage both years and in on base average in 1919. He was also the home run champion in each campaign and led in runs scored and runs batted in for the 1919 season. With that background, the following question can be asked: “Which of the 60 day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers from the 1946–60 period can be mentioned in the same breath with Ruth?”

Among the 60 day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers from the 1946–60 period, only two emerge with at least one blue ribbon in each of two different seasons. The first one was Paul Bruno of the 1947–48 Hammond Berries of the Class D Evangeline League. As shown in Table 7, in the 1947 campaign he won the pitching Triple Crown and also captured the slugging average crown as a hitter. Then, in 1948 he again claimed the leadership position in pitching victories.

Table 7. Paul Bruno’s Pitching and Batting Record for 1947 and 1948 with the Hammond Berries

|

Year |

IP |

W-L (%) |

SO |

BB |

ERA |

PA |

BA/OBA/SLG |

R |

HR |

RBI |

|

1947 |

253 |

25-5 (.833) |

260 |

45 |

1.96 |

459 |

.332/.434/.563 |

86 |

18 |

91 |

|

1948 |

248 |

22-5 (.815) |

228 |

55 |

2.87 |

404 |

.337/.479/.546 |

67 |

16 |

77 |

The only other day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeer with a pair of trophy-winning campaigns was Roy Parker. Playing with the Pampa Oilers in the West Texas-New Mexico League (Class C), he topped the loop in wins and strikeouts in 1949. Then while playing for the Clovis Pioneers in 1953, he led the circuit in runs scored. Table 8 provides the relevant details for Parker’s pitching and batting accomplishments. Also included is Parker’s performance line for 1951, during which he played for the Sherman-Denison Twins in the Class B Big State League.

Table 8. Roy Parker’s Pitching and Batting Record for 1949, 1951, and 1953

|

Year |

IP |

W-L (%) |

SO |

BB |

ERA |

PA |

BA/OBA/SLG |

R |

HR |

RBI |

|

1949 |

263 |

23-10 (.697) |

235 |

117 |

4.86 |

453 |

.296/.396/.582 |

96 |

24 |

91 |

|

1951 |

156 |

11-10 (.524) |

110 |

125 |

4.55 |

532 |

.345/.408/.559 |

100 |

18 |

92 |

|

1953 |

182 |

12-11 (.522) |

102 |

112 |

4.94 |

651 |

.353/.451/.690 |

177 |

41 |

160 |

Focusing on just one season of outstanding day-in/day-out double-duty performance, the player with the best pitching and batting record was Roy Sanner. As mentioned previously, in 1948 with Houma of the Class D Evangeline League, Sanner won the batting Triple Crown and finished a close second in each of the pitching Triple Crown departments.

While Bruno, Parker, and Sanner did have superb day-in/day-out double-duty seasons, there is a major caveat — each of their glowing double-duty campaigns was accomplished in the low minors (Class D or Class C). None of them was able to transfer those pitching and/or batting performances to the upper minors and none of them ever made it to the Big Show.

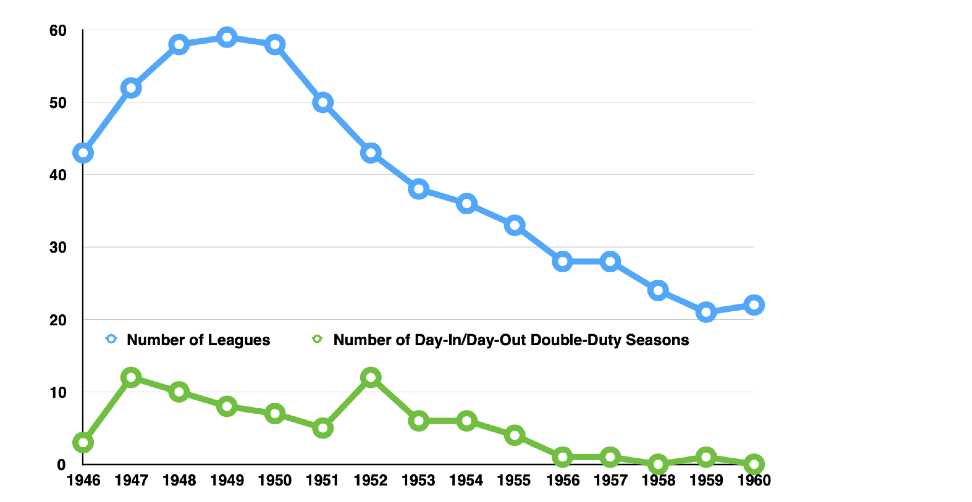

Figure 1. Year-By-Year Number of Minor Leagues (All Classes) and Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Seasons

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The primary objective of this research project was to ascertain which players (if any) were day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers in the minor leagues during the fifteen seasons between 1946 and 1960. As presented in the Results and Discussion sections, the principal research objective was achieved.7 As shown in Table 2, 59 players achieved a total of 75 day-in/day-out double-duty seasons. Moreover, consideration of all the information gathered in this research effort reveals four additional items that merit comment.

- The number of day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers pretty-much paralleled the decline in the number of minor leagues from 1952 through 1960, as summarized in Figure 1.

- Of the 75 day-in/day-out double-duty seasons produced in the 1946–60 period, 45 were accomplished in Class D, 26 in Class C, 3 in Class B, and just 1 in Class A.

- The league that produced the most day-in/day-out double-duty seasons was the Evangeline League, with a total of 13 — 5 when it was a Class D league (1946-1948) and 8 when it was a Class C league (1949-1957). The runners-up were the Class D Florida State League (10), the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League (7) and the Class D Georgia State League (7).

- The distribution of principal fielding positions is Outfield (45), First Base (16), Second Base (1), Third Base (7), Shortstop (2), and Catcher (3).

Based on the dearth of day-in/day-out double-duty diamondeers during the 1956–60 period, it would not be surprising if during the ensuing six decades (through the 2019 season) there were very few. However, that situation may be about to change. The encouraging double-duty performance achieved by Shohei Ohtani in 2018 (although an injury to his pitching arm limited him to just ten games and 52 innings on the slab) and his continued success from the batter’s box as a DH in 2019 could provide inspiration and motivation for others to pursue double-duty activity.

HERM KRABBENHOFT, a SABR member since 1981, began the research described in his “Double-Duty Diamondeers” article more than 60 years ago — in 1957 for a sixth-grade term paper addressing a claim that minor league pitchers were better hitters than major league pitchers. At that time, he wrote to Commissioner Ford Frick asking for some relevant information. Mr. Frick kindly sent him a complimentary copy of the 1956 edition of the TSN Baseball Guide, which Herm still has and uses.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Baseball-Reference for its comprehensive presentation of performance statistics — both minor league and major league — for all of the several hundred players I researched in detail for this project. While all of the minor league statistical information presented in this article was obtained from the relevant editions of the Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (published by The Sporting News), the Baseball-Reference website was particularly helpful for additional information and perspective for the players. Finally, I appreciatively thank my good friend Gary Stone for his superb reviewing of the first and last drafts of this manuscript.

Dedication

With enormous gratitude I dedicate this article to all of the Retrosheet volunteers whose outstanding contributions over more than 30 years have resulted in the invaluable Retrosheet website — each of them is truly a baseball research enabler! I especially wish to dedicate this article to four Retrosheeters who have been particularly helpful to me many, many times over the years — respectfully, to the memories of the late Clem Comly and the late David Vincent, and to Dave Smith and Tom Ruane.

APPENDIX ONE — Chronological Summary of Official Rules for Batting Average and Earned Run Average Titles (1946–60)

BATTING AVERAGE

-

For the seasons prior to 1950, there were no official rules defining the minimum requirements for determining the batting champion. The customary practice was to award the championship to the player with the highest batting average provided he played in at least 100 games.

-

For the 1950 and 1951 seasons, the official rules stated the following: “Batting championships, how determined, 10.18”

“BATTING CHAMPIONSHIPS 10.18. To be eligible for the individual batting championship of any minor league, a player must have appeared in at least two-thirds of the games played by his team. Thus, if a team plays 154 games, a player must appear in 102 games. If his team plays 150 games, he must appear in 100. If his team plays 140 games, he must appear in 93, etc.

- (a) To be eligible for the individual batting championship of a major league a player must be credited with at least 400 official ‘times at bat.’”

- For the 1952–56 seasons, the official rules stated the following: “Batting championships, how determined, 10.18 (a)”

“CHAMPIONSHIPS 10.18 (a). The individual batting championship of any league shall be the player with the highest batting average, if—he is credited with as many or more times at bat as the number of games scheduled for one club in his league during the season, multiplied by 2.6. However, if there is any player in the league with fewer than the required number of times at bat whose average would be the highest if he were charged with this at-bat total, then that player shall be awarded the batting championship. Example: The major leagues and many others schedule 154 games. 154 times 2.6 equals 400. If a player shall have, say, 390 times at bat and, by adding 10 imaginary hitless times at bat to his total, he would still have the highest batting average in his league, he shall be the champion batter.”

- For the 1957–60 seasons, the official rules stated the following: “Championships, how determined, 10.22”

“10.22. To assure uniformity in establishing the batting, pitching, and fielding championship of professional leagues, such champions shall meet the following minimum performance standards:

- (a) The individual batting champion shall be the player with the highest batting average, provided he is credited with as many or more total appearances at the plate in league championship games scheduled for each club in his league that season, multiplied by 3.1. Example: The major leagues schedule 154 games for each club. 154 times 3.1 equals 477. Some minor leagues schedule 140 games. 140 times 3.1 equals 434.

Total appearances at the plate shall include offi- cial times at bat, plus bases on balls, times hit by pitcher, sacrifice hits, sacrifice flies, and times awarded first base because of interference or ob- struction.”

EARNED RUN AVERAGE

-

For the seasons prior to 1951, there were no official rules defining the minimum requirements for determining the ERA champion. The customary practice was to award the championship to the pitcher with the lowest ERA provided he pitched at least 10 complete games.

-

For the 1951–53 seasons, the official rules stated the following:

“CHAMPIONSHIPS 10.18 (b). To be designated as the leader in his league’s pitchers in the minimum aver- aged number of earned runs allowed a pitcher is required to pitch at least as many innings as the num- ber of games scheduled for each team in his league. (This would be 154 innings in a major league.)”

-

For the 1954 season, the official rules were exactly the same as for the 1951–53 seasons except that the rule number was “10.17 (b)”

-

For the 1955–56 seasons, the official rules were exactly the same as for the 1951–53 seasons except that the rule number was “10.19 (b)”

-

For the 1957–60 seasons, the official rules were exactly the same as for the 1951–53 seasons except that the rule number was “10.22 (b)”

APPENDIX TWO — Comparative Statistics for Selected Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 Jay Jaffe, “Shohei Ohtani and Beyond: A History of Double-Duty Players,” FanGraphs, April 6, 2018.

2 The “Official Baseball Rules, 2019 Edition” as provided on MLB.com (the official website of Major League Baseball) have the following rule: 9.22 Minimum Standards for Individual Championships … “To assure uniformity in establishing the batting, pitching and field- ing championships of professional leagues, such champions shall meet the following minimum performance standards: (a) The individual batting, slugging or on-base percentage champion shall be the player with the highest batting average, slugging percentage or on-base percentage, as the case may be, provided the player is credited with as many or more total appearances at the plate in league championship games as the number of games scheduled for each Club in his Club’s league that season, multiplied by 3.1 in the case of a Major League player and by 2.7 in the case of a National Association player. Total appearances at the plate shall include official times at bat, plus bases on balls, times hit by pitcher, sacrifice hits, sacrifice flies and times awarded first base because of interference or obstruction. Notwithstanding the foregoing requirement of minimum appearances at the plate, any player with fewer than the required number of plate appearances whose average would be the highest, if he were charged with the required number of plate appearances shall be awarded the batting, slugging or on-base percentage championship, as the case may be. (b) The individual pitching champion in a Major League shall be the pitcher with the lowest earned-run average, provided that the pitcher has pitched at least as many innings in league championship games as the number of games scheduled for each Club in his Club’s league that season. The individual pitching champion in a National Association league shall be the pitcher with the lowest earned-run average provided that the pitcher has pitched at least as many innings in league championship season games as 80% of the number of games scheduled for each Club in the pitcher’s league.”

3 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Editors, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd Edition , (Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1977). See also Neil J. Sullivan, The Minors, (New York: St. Martins Press, 1990), Part Two.

4 Shortly after hurling a two-hitter in Houma’s 4-0 triumph over Abbeville on August 29, Sanner bolted from the Houma Indians because of a financial disagreement, thereby freezing his Evangeline League statistics. One can only speculate what Sanner might have accomplished in Houma’s remaining eleven games — he might have even emerged with the pitching Triple Crown! On August 10, Houma had sold his contract to the Dallas Rebels of the Class AA Texas League for the 1949 season. An agreement was subsequently worked out and Sanner ultimately ended up finishing the 1948 campaign with Dallas, playing in seven games, producing a .364 batting average (8 hits in 22 at bats) and a 1-1 W-L record with a 4.76 ERA.

5 Ray Lee, “Once Over Lightly,” The Town Talk (Alexandria, Louisiana), May 10, 1947, 10.

6 McDaniel’s career-starting 19 scoreless innings streak was the longest consecutive innings scoreless streak by a pitcher from the start of his career since Al Worthington had hurled a string of (also) 19 in 1953 with the New York Giants. Von’s career-starting 19 shutout innings streak was six innings short of the then major-league record of 25 innings accomplished by George McQuillan in 1907 with the Philadelphia Phillies. The current record is 39 consecutive scoreless innings by Brad Ziegler of the 2008 Oakland Athletics; McQuillan’s 25 consecutive scoreless innings streak is still the National League record.

7 Some of the results described in this article were presented at the SABR Virtual meeting in July 2020 — Herm Krabbenhoft, “Day-In/Day-Out Double-Duty Diamondeers, Full-Time Two-Way Players (1946–60),” SABR Virtual: Day 4 (July 12, 2020) — YouTube [1:29:23].