Deadly Minor League Bus Trips Hard to Forget

This article was written by Jim Price

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

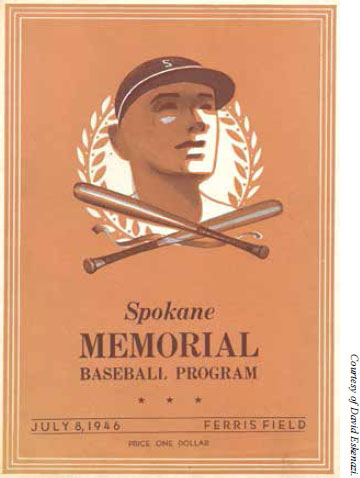

A memorial program was conducted in Spokane in July to commemorate the eight Spokane players and the bus driver, who died on June 24, 1946, when their team bus careened off a narrow road in the Cascade Mountains. (Courtesy of David Eskenazi)

Blessedly, professional baseball has had very few terrible moments, incidents that end with loss of life, calamity, or great destruction, leaving behind indelible memories.

Serious fans almost everywhere know about these, as readily as they recall the feats of Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson, the durability of Lou Gehrig and Cal Ripken, the shame of the Black Sox, or the recurring dominance of the New York Yankees.

As I discovered at my first SABR convention, fans also respond to mention of my home, Spokane, Washington, with questions about the bus accident that killed nine of that city’s players. Almost eight decades later, that 1946 catastrophe remained the worst of its kind in American professional sports. The second worst involved another minor-league team, the Duluth Dukes, and its bus in another league just two years later.

Those and a few less frightful events underline the perils of minor-league travel and team travel in general. Most known examples were a consequence of late-night bus rides. All baseball-related fatal accidents involved lower minor-league or college teams. In almost a century and a half, no major-league American sport has had a team-travel fatality.

Both deadly accidents took place in the aftermath of World War II. Nationwide, worn-out vehicles and parts shortages often left passenger equipment in precarious condition. Even in our own lives, deferred maintenance can take its toll.

Since then, with Major League Baseball wielding almost complete oversight of the professional game, standards are higher and the buses better. Nonetheless, in the lower minor leagues, where smaller cities may be separated by hundreds of miles, late-night bus rides remain the most affordable option. Not all notable bus accidents occurred long ago. Not all involved professionals. Only a few ended in death. Considering the number of trips over many decades, the national pastime should give thanks that the consequences haven’t been worse.

The basic facts of Spokane’s disaster, while the city’s team was a member of the Class-B Western International League, are well known. But details, collected over seven-plus decades, describe personal tragedy, horror, pain or heartbreak. A few were life-changing, not always in a good way.

The second terrible accident involved a 1948 Northern League team, the Dukes from Duluth, Minnesota. This is not as well-remembered. Horrible things happened there, too. In two years, the profile of minor-league baseball had changed quite a bit. Most minor leagues had not operated since 1942. By war’s end, many experienced minor leaguers had played in fast company, some of it in the service. As a result, in 1946, pro ball was awash with talent. With the economy on the rise, and television not yet ubiquitous, fans flocked to ballparks in more than 300 markets. Three years later, the minors reached their peak with 59 leagues representing 438 cities.1 They employed close to 7,000 players. Today, the constricted minor leagues include only 120 teams. Each major-league franchise has four affiliates.

The Spokane and Duluth teams were typical of their year. Duluth’s players in Class C were much younger, averaging 21.5 years. Put simply, they had far less history. Few had gone to war. Few were married. Only five had prewar experience. In 1946 the Indians players averaged 26.1 years old. All of them had played before or during the war. A clear majority were married. All but three had been servicemen. The WIL was the second-best league in the West.2

Spokane, with no apparent weakness, was a logical pennant contender. Veterans, not just the military kind, clogged the roster. They had Bob Kinnaman, the best pitcher, and top outfielder Levi McCormack from the city’s 1940 and 1941 regular-season champions. Third baseman Jack Lohrke, on option from San Diego’s Pacific Coast League team, and first baseman Vic Picetti were considered top prospects. Several teammates were in the midst of, or near the end of, long careers.

Lohrke, 22, had been in the Army, where he had survived combat at the Battle of the Bulge. Then, after his discharge, he was bumped off a military flight, which subsequently crashed, killing everyone aboard.3 He would become known as “Lucky Lohrke,” a nickname he disliked. Picetti was a protégé of Oakland manager Dolph Camilli, the former National League MVP. In 1945 Picetti had gone directly from high school to the PCL, where Camilli, who later told me, “He was the greatest prospect I ever saw come straight out of high school,” benched himself so Picetti could replace him in the lineup.4

Five veteran right-handers led Spokane’s pitching staff. All of them had played before the war. Former Washington State College star Kinnaman, a 22-game winner for the 1941 Indians, belonged in the Coast League. But, like Picetti and outfielder Bob Paterson, he’d been crowded off Oakland’s roster by prewar regulars.

Milt Cadinha and Joe Faria were boyhood friends from Northern California’s East Bay area. Cadinha, already known to WIL fans, had twice won 13 games for Tacoma (in 1940 and 1941), and he was off to an 8-1 start.5 Darwin “Gus” Hallbourg and Dick Powers also came on option from San Diego. Hallbourg had 45 wins over three pro seasons. Powers, a seasoned East Bay semipro, had spent the last two years with Sacramento in the PCL.

Like Paterson, the other regular outfielders, Bob James and McCormack, could hit. McCormack, 33, a handsome Native American from the Nez Perce reservation, had starred for both Spokane title teams. George Risk, a former football and baseball standout at Oregon’s Pacific University, was the shortstop. He and infielder Fred Martinez, a Dodgers farmhand before the war, were batting well above .300. League veteran Mel Cole was set to be the catcher, but instead, plagued by injuries, he became the manager. Just before Opening Day, team owner Sam Collins fired Glenn Wright because the former National League infielder had disappeared on a drunk. When Wright managed Wenatchee’s first-place team in 1939, Cole had been his catcher.6

Recently, Collins had signed a pair of seasoned pros, each with a bit of big-league experience. Ben Geraghty succeeded Martinez at second base. Chris Hartje, a former Brooklyn Dodger who had been working out with Oakland, was going to step in for Cole.7

On Monday morning, June 24, 1946, Spokane players gathered outside Ferris Field, waiting to board the bus that would carry them almost 325 miles over land and sea. Ahead, with the season nearly half over, lay a weeklong series with Bremerton. Summer had begun, but it was wet and dreary. This would be a long, slow trip, maybe 12 hours, twice as long as it takes today.

The wooden ballpark, built as a 1936 WPA project, shared the former Spokane Interstate Fairground with a thoroughbred racetrack, three miles east of downtown, just north of Sprague Avenue, which intersects the city. In those days, Sprague doubled as a segment of US 10, stretching east toward the Idaho state line and west toward Seattle.

On Sunday, Spokane had divided a split doubleheader with Salem, winning the night game, 11-10, with the help of Lohrke’s four hits.8 The team picture, which became a collectible, was taken between games. Salem, after opening the season with a 13-game win streak, now clung to the lead, barely ahead of Wenatchee, with three teams crowded behind them. All five had winning records. Though the Indians were fifth, with a record of 32-26, 5*A games behind.9

Cole and 15 teammates boarded their Washington Motor Coach charter, a 20-passenger version of a school bus, a bit before 11:00 A.M. Glen Berg, young but experienced, had the wheel. Cadinha, Faria, and their wives had gone ahead in Faria’s prewar Buick.

With two-lane highways the norm, they would mostly follow the route that has since become Interstate 90, heading south to Ritzville, west through the Columbia Plateau—among the world’s largest deserts—and across the Columbia River, farther west to Ellensburg, then over Snoqualmie Pass to Seattle, where they would catch a ferry.

A couple of hours after the team left, business manager Dwight Aden, who had been the team’s prewar center fielder, received a call from San Diego. The Padres had recalled Lohrke, who was hitting .345 and had 28 extra-base hits. Long-distance phone lines were out of service in the middle of the state, so Aden asked the state patrol to get an Ellensburg officer to deliver the message when the Indians stopped to eat at Webster’s Café.10

The team arrived about 5 o’clock. While the players ate, Berg drove to the company’s local garage, hoping to replace the bus. Told he had a better vehicle than anything on the lot, he settled for minor repairs. When Berg rejoined the team, Lohrke grabbed his gear, said goodbye, hitchhiked back to Spokane and, after hearing the dreadful news, caught a train to San Diego.

The team continued west. As a holdover from the war, there was no daylight saving time, so the overcast was fading to dusk, and the drizzle had turned into mist, as the bus labored up and over Snoqualmie Summit. At about 8:00 P.M., it rounded Airplane Curve and started down the long straightaway. In those days, US 10, one lane in each direction, hugged the southern edge of the deep, narrow canyon. Stout wood posts, strung with cable, separated westbound traffic from the ravine.

Hallbourg told the Seattle Daily Times that he had seen the Snoqualmie River glistening far below. The view prompted him to twist in his front-row seat and tell Kinnaman, two rows back, “‘This would be a hell of a place to go over, wouldn’t it?’ I turned back, and we were going through the fence.”11

The Indians were almost three miles past the summit when, as Berg, McCormack, and Geraghty told investigators, a black, eastbound sedan came into view, crowding the center line. It may have clipped the bus. Berg swerved rather than applying the brakes, fearing he might lose traction on the slick road. But the right-side wheels slipped onto the shoulder. Though he nursed the front back onto the pavement, the rear duals ricocheted off the lip and slid the bus sideways into the cable, where it began clipping off posts. After 100 feet or so, it broke through. Tumbling down the rocky hillside, the bus struck a boulder, caught fire, bounced onto its left side, struck another big rock, then rolled again before stopping right side up, astride a log. It had fallen an estimated 350 feet, scattering men and equipment across the hillside. After moments of stunned silence, the gas tank exploded.

Six died at the scene. Cole, Risk, and Paterson, seated on the left side, burned to death. Fire or blunt force trauma killed Kinnaman, Martinez, and James, who sat right across the aisle. Picetti, spread-eagled on a boulder with terrible injuries, died on the way to Seattle’s Harborview Hospital. Reserve pitcher George Lyden died around noon the next day. Hartje, burned over most of his body, passed away on Wednesday. He and Lyden had been with the Indians less than a week.

Survivors ejected through one of the aluminum-framed windows were seriously injured. Geraghty, launched almost at once, struck a boulder that left him with a gaping scalp wound and a broken knee. Powers had a skull fracture, a broken neck, and a broken collarbone. Although McCormack, lame in one hip, walked away, his nose was smashed.

Those still on board escaped through window openings. Hallbourg struggled to free his hips and ended up with burns on his pitching arm. Pete Barisoff, the staff’s only left-hander, also crawled out. When he heard Irv Konopka crying for help, he dragged the backup catcher through the empty frame. Konopka, a former University of Idaho football player drafted by the Detroit Lions, had a broken shoulder, while Barisoff suffered a foot injury.

Berg, engulfed in flames, escaped through the battered doorway. He remained in Seattle’s Virginia Mason Hospital for almost four months, burned badly on his arms, legs, and head.12 Later, he became a truck driver, admired for his safety record.13

By the time rescue teams arrived, they worked in steady rain. The fire burned until dawn.

Professional baseball responded without precedent. The major leagues contributed $25,000 from All-Star Game receipts. PCL rivals Seattle and Oakland (managed by Casey Stengel) played a Ferris Field exhibition. Wenatchee hosted Sacramento, its parent club. Including donations from leagues, teams, and fans, the Spokane Baseball Benefit Fund raised $118,567.41, the equivalent of about $1.9 million in 2024 dollars.14 Supplemented by bus company insurance, distributions were prorated. Cole, Martinez, and Hartje left pregnant wives, and widows with children received larger shares.15

Collins had secretly planned to send Picetti, homesick for his widowed mother and fiancée, home for a few days, after the Bremerton series. Instead, the women escorted his body back to San Francisco and buried him with his wedding ring.16

With a lineup cobbled together from Western International League rivals, former professionals and a semipro or two, Spokane resumed its schedule on the Fourth of July. Although Cadinha, Faria, and Hallbourg anchored the pitching staff, the Indians were nearly inept at the plate and in the field. They finished with a 54-78 record. Glenn Wright stepped in as manager until Geraghty was able to take over.

Geraghty stayed on in 1947. Stocked with prospects from the Brooklyn Dodgers, his old organization, he guided the Indians to within one percentage point of the WIL title. He went on to become a legendary, pennant-winning minor-league manager, haunted by the accident, and a protector of developing players, particularly Henry Aaron. However, a heart attack killed him in June of 1963. He was only 50 years old.17

Powers recovered, but it took almost two years. He worked as a meat broker and a real estate agent. McCormack rejoined the Indians in 1947 and played well until his aching hip forced him into retirement. He became a mail carrier. The three active pitchers and Barisoff played in 1947, then moved on with their lives. Cadinha became an insurance agent. Faria ran an East Bay celebrity hangout. Hallbourg settled east of them, near Modesto, where he spent 37 years with Pacific Telephone.18

Barisoff and Konopka weren’t so fortunate. Barisoff died on November 12, 1949, trapped inside when fire swept through his Los Angeles County home. Konopka, who saw action with Boise’s Pioneer League team in 1949, died of cancer in 1970.19

Lohrke played with the San Diego Padres for the rest of the season and batted .303 with 8 home runs and 48 runs batted in. He went on to seven seasons in the National League (with the New York Giants and Philadelphia Phillies) and he ended his 15-year professional baseball career as player-manager with the Tri-City Braves of the Northwest League. Afterward, he worked as a security guard in San Diego.20

Today, as part of Interstate 90, the former US 10, cut further into the hillside, carries only eastbound Snoqualmie Pass traffic. Westbound vehicles follow a relatively new path on the north side of the canyon.

The bus, carrying members of the Duluth, Northern League team, is shown on July 24, 1948, after it collided with a truck that that had crossed the center line. Five Duluth players perished in the accident. (Jack Gillis, Minneapolis Star, July 24, 1948, Courtesy Minneapolis Star)

A SECOND DISASTER

Exactly 25 months after Spokane’s accident, right around noon on a sunny Saturday, July 24, 1948, Duluth Dukes manager George Treadwell and four of his players died north of St. Paul, when a truck loaded with dry ice veered across the center line and slammed into their team bus.21 The Minnesota-based Dukes, losers of two one-run games the night before in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, were headed north on Highway 36 just before its intersection with Dale Road. They were bound for St. Cloud, contenders with a 40-34 record.22

By contrast, most of the ongoing news coverage of this accident came from league cities and their neighbors. Probably, it was underreported. Except for immediate notice, it attracted little attention from the national media. There was no unusual setting. There were few complex backstories. There was surprisingly little drama. Most of it unfolded in less than two hours. But it was awful.

Minnesota Highway Department investigators determined that the washboard section of road thought to be the cause was more than 30 yards from the point of impact. Instead, they speculated that the truck’s worn steering mechanism may have failed, causing the driver, James Grealish, to lose control. Grealish, a Marine veteran with a wife and three daughters, and Treadwell, well known in the lower minor leagues, died instantly.

The truck had hit the 18-passenger former school bus on the left front corner, knocking it onto its right side. Their gas tanks ruptured and both vehicles burst into flames. A farmer named Frank Kurkowski, working nearby, heard the crash, ran to the scene, broke out the rear bus window and dragged five men to safety. Passing motorists rescued the rest.

Outfielder Gerald “Peanuts” Peterson, pitcher Don Schuchman, and outfielder Gil Krirdla, who played under the name Gil Trible, among the few Dukes with previous pro experience, also died on impact or burned to death. Second baseman Steve Lazar, his head split open, died two days later. Every survivor was injured to some degree. Many had burns. Some had inhaled toxic fumes. Several had fractures. Seven remained in critical condition for days.23

Pitcher Don Gilmore and all-star catcher Bernie Gerl were hurt the worst. In addition to burns, Gilmore was left with a broken left thigh and a mangled right ankle.24 Gerl, the last man rescued, had extensive burns and internal damage caused by the fire and its fumes. “My face looked like a breaded pork chop,” he recalled in 2013. “It made hamburger out of a lot of the guys. To describe some of the injuries, you couldn’t write it.”25

Duluth outfielder Chris “Bud” Dubia had a broken jaw, broken ankle, and broken ribs. Rookies Don Ritonya (broken arm, broken jaw, and broken leg) and John Vanderwier (fractured pelvis, deep wounds, and internal injuries), made the critical list though neither had pitched in a game. Shortstop Joe Becker, whose dad (also named Joe Becker) managed in the Western League, had lost skin on his left hand. He and pitcher Sam Paitich, his face badly burned, were hospitalized until the end of the year.26

The funeral service for Peterson, once a multisport star at Proctor High School, on Duluth’s rural outskirts, and the most popular player for the 1947 Dukes, attracted almost 2,000 people. Treadwell’s service, right across the state line in Superior, Wisconsin, drew an estimated 1,000.27

First baseman Mel McGaha and infielder Elmer Schoendienst, whose older brother Red was the second baseman and future manager of the parent Cardinals, were less injured. Both resumed their careers in 1949. McGaha, after years as a minor-league player-manager, managed the American League teams in Cleveland and Kansas City. Elmer Schoendienst spent a year in the Central League then gave it up and played semipro ball with another brother, Frank.28

Most of the others played only a year. Lou Branca, after pitching for the Dukes in 1949, coached the highschool team in Rochester, Minnesota, home of the Mayo Clinic, and ended up in the state coaches hall of fame. Recently married Eull Clark played in 1949. Dubia didn’t return to action until 1950, when he split 29 games between Duluth and Aberdeen. Then he rejoined the Army and retired, highly decorated, as a colonel. Vanderwier made a belated debut in 1950, posting an 8-6 record for Hamilton of the PONY League. Paitich, who was on the team but never got into a game, became a local tavern owner.29

Aces Joe Svetlick (10-4, 2.39) and Bob Vogeltanz (10-3, 2.54) also played only one more year. Svetlick, after completing the 1948 season, pitched well again in 1949, then joined the Air Force. Vogeltanz, promoted to Columbus of the Sally League, won twice in relief. But his thigh injury flared up, and the short, stocky ex-Marine was finished by June.

Gilmore, also a pitcher, became a law officer and owned a security company. Beginning in 1969, he served six terms as a Republican state legislator in Ohio.30

“There are people who have been through things as horrible and terrifying as that was,” he told the Duluth Tribune/News at a 40th anniversary gathering in 1988. “But it’s been 50 years and I still dream about it twice a week.”31 Gilmore died on October 15, 2003, at the age of 75.

Only one other persisted. Gerl, who had lost 70 pounds during 40 days of hospitalization, underwent more than a year of intense recovery. After sitting out 1949, he batted .302 in 1950 for a St. Louis affiliate, Montgomery in the Southeastern League. After another year off, he rejoined Duluth, which needed a catcher, in 1952 and 1953. He liked to brag that, in his final season, he drove in more runs than Fargo-Moorhead’s hometown rookie hotshot, outfielder Roger Maris. Afterward, Gerl, a lifelong resident of Joliet, Illinois, went to work in his local Coca-Cola warehouse. He took charge five years later, and then became a regional Coke executive.32

Professional baseball and the public again responded generously. The league’s other seven teams loaned a dozen players. The Cardinals organization sent nine. The American Association’s Triple-A franchise in Minneapolis loaned another. Led by a fundraising effort highlighted by home-and-home Northern League benefit games and broadcast over radio stations in four states, more than $75,000 was raised and distributed to families of the victims.

Like Spokane, Duluth had a player who avoided possible death. St. Louis had promoted an 18-year-old right-hander named Sam Hunter, who missed the train that would have taken him from Chicago to Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Instead, he caught a bus and, by the time he arrived, the team had gone.33

Duluth returned to action seven days after the accident, meeting Superior, its Northern League neighbor from across the Wisconsin state line. Ted Madjeski, in his third year as a player-manager at age 26, succeeded Treadwell as manager. The Dukes finished the season with 53 wins and 61 losses.

Surviving players held 30th and 40th reunions at the city’s Wade Stadium. Five teammates joined Gilmore and Gerl, who gathered on the 30th anniversary for a July 21, 1978, Duluth Herald photo. By the 50th anniversary. Gerl was the only one left. Nonetheless, he made the eight-hour drive for 15 straight years, a streak that didn’t end until 2010.34

Viewed from the distance of time, Gus Hallbourg and Bernie Gerl, each a last survivor, modeled gratitude and fulfillment while living many more productive decades.

“I am one of the great lucky guys alive,” Hallbourg said before the 50th anniversary of Spokane’s accident.35 He’d completed a fine career. He golfed. He gardened. He was popular in his community. He had a loving family. When he died on October 13, 2007, he was 87 years old.

Gerl also made the most of his remaining years. He, too, dreamed about his terrible day. But there he was, two years later, successfully back in uniform, married after a six-month postponement, using the insurance settlement to buy and furnish a home, and traveling the world for his employer. He had nine grandchildren and a fleet of great-grandchildren. In later years, he relished his time in the spotlight as the man who refused to let us forget his unfortunate teammates.36

Gerl, the last of the last survivors, died on November 7, 2020. He was 94 years old.

No other American professional teams in any sport have experienced fatalities.

Only one serious accident has affected a major-league team. That involved the California Angels. On May 21, 1992, the first of two team buses, headed to Baltimore from New York City, swerved off the New Jersey Turnpike at 1:50 A.M. and plunged into a grove of trees. The bus rolled onto its right side and left a dozen team members injured.37

Manager Bob “Buck” Rodgers, briefly trapped in the wreckage, was hurt the worst. The former Angels catcher suffered a crushed right elbow, a damaged left knee and a broken rib. He didn’t rejoin the team until August 28. The driver, who had had five speeding violations, was cited for careless driving.38

When it came to bus accidents, baseball’s other known multiple player deaths involved amateurs. Other minor-league incidents did not end in athlete death. The numbers are small. That may be a miracle.

JIM PRICE has been a SABR member since 1979. He received the Macmillan-SABR Award for “A Half Century of Pain,” marking the Spokane accident’s 50th anniversary, which appeared in the Spokane Spokesman-Review on June 24, 1996. A former beat writer, official scorer, and public-address announcer in three professional leagues, he got his first paid daily newspaper byline in 1952. A longtime Spokane resident, he has been a Spokane Indians publicist and play-by-play announcer, the track announcer and publicist at several thoroughbred racetracks, and the sports information director at Eastern Washington University. He retired from the Spokesman-Review in 2003. He has contributed to several books, including Rain Check, the 2006 SABR convention publication, and Drama and Pride in the Gateway City, the story of the 1964 St. Louis Cardinals, and to popular-music biographies.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Descriptions and details of the Spokane accident represent accumulations of information from the June 25-29, 1946, editions of the Spokesman-Review and Spokane Daily Chronicle, the Seattle Daily Times, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and the Seattle Star, along with dispatches from the Associated Press and United Press, and the author’s telephone conversations with survivors and their families. Many of these details have been printed in his Spokesman-Review anniversary stories on June 22, 1986, June 24, 1996, June 18, 2006, and June 19, 2016.

NOTES

1 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd Edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997).

2 Baseball-reference.com provided rosters and player records for the 1946 Spokane and 1948 Duluth teams, supplemented by the author’s interviews.

3 Ron Fimrite, “O Lucky Man,” Sports Illustrated, November 14, 1994.

4 Author’s telephone interview with Camilli in June 1986, reported in the author’s article in the Spokesman-Review, June 24, 1986.

5 Cadinha went on to win 16 games (against seven losses) in 1946 for Spokane.

6 Conversations with Dwight Aden and various surviving players.

7 Various articles printed in the Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 17-20, 1946.

8 “Spokane Wins Salem Series, 4-3,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 24, 1946: 7.

9 “Spokane Wins Salem Series, 4-3.”

10 Author’s 1986 conversations with Aden and his phone conversation with Lohrke.

11 Hallbourg repeated this quote, frequently printed in the accident’s aftermath, to the author in their June 1986 telephone conversation.

12 This and other Glen Berg details came from the author’s several conversations with his daughter Debbie and were summarized in the author’s Berg obituary for the Spokane Spokesman-Review, November 2, 2003.

13 Berg had driven more than a million consecutive accident-free miles, according to a telephone conversation with Teamsters Local 690, Spokane, on October 31, 2003.

14 CPI Inflation Calculator, accessed October i, 2023, and updated April 16, 2024.

15 “Bus Crash Fund Totals $114,805,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, December 21, 1946: 10. Details updated in author’s telephone interview with Pat Lyden, June 2016.

16 Conversations with Dwight Aden in June 1986 supplemented in June 2006 during telephone interviews with Vic Picetti’s sister, Bev Schumann, and his former fiancée, Bety Evans King.

17 “Survivor of Smash Ben Geraghty Dies,” Spokane Chronicle, June 18, 1963: 13. Aaron’s admiration detailed in Kenny Kerr, “Kenny Kerr’s Korner,” Bristol (Tennessee) Herald Courier, October 10, 1974: 21.

18 From the author’s telephone conversations with Powers, Cadinha, Faria, and Hallbourg in June 1986.

19 “Survivor of 1946 Wreck Dies in Fire,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, November 15, 1949: 15. Konopka’s death was detailed in Mike Lynch and Alden Cross, “Baseball’s Darkest Night,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 20, 1971: 109-112.

20 See https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=lohrke001jac.

21 “Four Deaths, Injuries Riddle Dukes’ Roster,” Eau Claire (Wisconsin) Leader-Telegram, July 25, 1948: 10.

22 “5 Die, 14 Hurt in Bus-Truck Crash,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 25, 1948: i; Halsey Hall, “Northern League Continues; Help Promised Duluth,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 25, 1948: 31.

23 “5 Die, 14 Hurt in Bus-Truck Crash.”

24 “Eight Duluth Players Still Stick by Game,” Rap-id City (South Dakota) Journal, August 6, 1948: ii.

25 Jon Nowacki, Duluth News-Tribune, July 18, 2013 (page unknown).

26 “‘Duluth Fund’ Contributions Total $115,” Johnson City (Tennessee) Press, August 12, 1948: 32.

27 “Send 26 Players to Bolster Dukes,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, July 28, 1948: 17.

28 See https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=schoenooielm.

29 “Col. C.F Dubia dies at 66,” Columbus (Georgia) Ledger-Enquirer, July 31, 1990: 27.

30 H.R. 142, In Memory of Don Gilmore, Ohio House Journal, January 27, 2004.

31 Jon Nowacki, Duluth News-Tribune, July 12, 2008 (page unknown).

32 Author’s telephone conversation with Gerl in June 2016.

33 Joel Rippel, “The 1948 Duluth Dukes Bus Crash,” The National Pastime (Society for American Baseball Research), 2022.

34 Dave DeLand, “A Vivid Memory,” St. Cloud (Minnesota) Times, July 24, 2015: Ai, A2, A4.

35 Personal conversation with author, 1998.

36 Author’s telephone conversations with Gerl, June 2016.

37 “12 are injured as Angels’ team bus crashes,” Atlanta Journal, May 21, 1992: 85.

38 Helene Elliott, “13 Injured in Angel Bus Crash,” Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1992: C1.