Declaration of Victory: The Meaning and Achievements of the Stanford University Baseball Team’s 1913 Japan Tour

This article was written by Yusuke Suzumura

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

Stanford and Keio players discuss the controversial ninth-inning call on May 29, 1913. (Rob Fitts Collection)

The Stanford University Baseball Team is closely connected to the development of baseball in Japan. This stems from 1904-05, when Waseda University was planning an expedition to the United States and negotiated with different universities there, and Stanford University was the first to respond. One of the reasons Stanford accepted Waseda’s request was that Zentaro Morikubo was a student at Stanford and facilitated negotiations between the two universities.1 Zentaro was the son of Sakuzo Morikubo, a member of the House of Representatives in Japan’s Imperial Diet; Zentaro later became a member of the Japan Amateur Athletic Association and was appointed a member of the Japan Baseball Umpires’ Association (an organization founded in 1916 with the intent of spearheading the establishment of baseball rules in Japan). As such, Zentaro Morikubo was a prominent figure in the baseball world at the time.2

The Waseda team traveled to the United States in 1905, played against the Stanford Cardinals twice, and lost both games. They lost because the Waseda team’s play did not extend much beyond the rudimentary stages of throwing and hitting the ball, whereas the Stanford team approached the sport in an organized and systematic manner.3

On March 31,1913, Keio University announced an invitation to the Stanford University baseball team to visit Japan later that spring.4 At the time, St. Mary’s College and Santa Clara University were the two best college baseball teams on the West Coast, and Stanford was second to these universities, alongside the University of California and the University of Washington. Stanford had won games against all of these universities before they visited Japan, and therefore Keio was “expected to probably lose.”5

An 11-man contingent boarded the passenger ship Nippon Maru and departed San Francisco on May 10, 1913.6 Graduate student R.W. Wilcox was the manager.7 The players were Ray Maple, pitcher; Al Gragg, pitcher; Leslie Dent, catcher; Tom Workman, first base; Louis Cass, second base; Pete McCloskey, third base; Zeb Terry, shortstop; Arthur Halm, left field; Walter Argabrite, center field; and Heinie Beeger, right field.8

The trip was scheduled for 10 weeks, longer than any previous trip by a Stanford team. They planned to play at least 12 games, starting with Keio in Japan, with a two-week visit to Hawaii on the way home. Keio provided 7,000 yen ($3,500) to cover the trip expenses. In 1913, 7,000 yen was equivalent to approximately 28 million yen (approximately $240,000) in 2022.9 In addition, the Stanford baseball team raised $200 from a match against the Santa Cruz Colored Giants; the university donated $250; and the Quadrangle Club donated $50, making for a total of $500.10 With the funds provided from the Japanese side and the donations from Stanford, the large amount of money they were able to raise suggests high expectations for the trip in both countries.

The Stanford group arrived at Yokohama around 8 A.M. on May 27.11 The Japan Times reported, “Immediately after the health inspection, the six-foot huskies were swarmed by a gang of newspaper reporters, and the Keio ball players and students who went out in a launch to meet them. ‘Banzai’ and college cheers were exchanged on the deck.”12 The team held a press conference at the request of the Japanese press, in which they described how they spent their time training during the 17-day voyage on the Nippon Maru. “Thankfully, the seas were calm, so we were able to practice every day. We still ended up dropping 15 of the four-dozen balls into the sea. However, perhaps because of the daily practice, everyone gained weight, with some of us gaining as much as 12 kg [about 26 pounds].”13

Obviously, the team had indulged in a comfortable lifestyle during the voyage. However, when the Stanford players arrived at Yokohama, despite their massive weight gain, their physiques drew little attention from the Japanese, who remarked only that their physiques were “imposing.”14

By way of example, the Yomiuri Shimbun favorably introduced the players in the following terms: “They are all elegant young gentlemen, dressed in winter suits and caps. Their physiques seem particularly imposing when one looks at the All-Philippines Baseball Team. Based on this alone, they would seem to have the power to overwhelm the Japanese baseball world.”15

The All-Philippines Baseball Team had come to Japan on May 10, and had planned to stay until June 1 and play a total of 10 games with Waseda, Keio, Meiji University, and Yokohama Commercial School.16 Some of the games were canceled due to rain, and the Philippines team ended up playing eight games, of which it won only one, against Waseda, losing the other seven.17

The All-Philippines Baseball Team was said to have “selected the very best of Philippine baseball,” with a total of 16 members, of which 13 were players, and one was a substitute. The players were generally of medium build and height, and while three had excellent physiques, another three were of smaller stature.18 While the results of the games are not necessarily always decided on the basis of physique, when one considers that the Philippines team had won only one out of the eight games, it is perhaps unsurprising that people thought that physique played a part in the team’s poor performance. The comment that “[t]heir physiques seem particularly imposing when one looks at the All-Philippines Baseball Team” can be taken not only as a comparison of the physiques of the All-Philippines players and the Stanford University players but also as an indication that there were high expectations for the latter based on the superiority of their physiques.

It should be noted that an article in the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun reported that “the players bore no signs of fatigue and were very comfortable during their 17-day voyage, with each gaining about 750 g [about 1.5 pounds].”19 Compared with the Yomiuri Shimbun article, none of the players seems to have gained a large amount of weight. While it is difficult to judge which description is accurate, we can nevertheless deduce that the players did indeed gain weight during the voyage.

The Stanford team was evaluated favorably by the Japanese during their time in Japan, as illustrated by the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun: “They are all the very best of young gentlemen morally influenced by Dr. Jordan, who resembled a messenger of the god of peace, and they seem to be very pleasant and friendly upon first meeting in the American style.”20

“Dr. Jordan” was David Starr Jordan, who became the first president of Stanford University in 1891 and also became the first chancellor of the university in June 1913. Jordan visited Japan frequently from 1900 to investigate his academic specialty of ichthyology, the study of fish.21 Moreover, Jordan was a researcher, university administrator, anti-imperialist, and antiwar activist. Rather than his role as an ichthyologist and educator, the assessment of Jordan in Japan related to his opposition to the anti-Japanese-immigration movement in the United States, which was the most significant concern between the two countries at the time; he was on the side of the Japanese, arguing that “no parliament should pass the Japanese Exclusion Act.”22 In addition, he was described as “a great player for peace” who “loved peace and was convinced that peace was a global truth.”23

Thus, the baseball players were depicted as gentlemen inspired by Jordan precisely because they were at Stanford University. In addition, the more distinctive players in the group were thus described:

Pigeon-toed and with a liking for beans, Cass is the odd man out in the group—so pigeon-toed in fact that his fellows tease him every which way. He made everyone laugh by saying that he was going to advertise himself in the papers as a pigeon-toed rickshaw man when he arrived in Tokyo. Argabrite’s family runs a bean shop, and he also has a great liking for beans, hence the nickname “Bean.” Workman is extremely timid and never left his lifeboat during the voyage.24

While matters such as physique and family business have nothing to do with baseball itself, these topics were a good source of information to better know the players. The fact that such articles seeking to convey the personalities of the players were published, even if they were primarily intended to amuse the readers and satisfy their curiosity, demonstrates that people had a high level of interest in the Stanford University baseball team.

Having thus attracted people’s attention, how did the Stanford players adjust once they were in Japan? They started practicing at 1 P.M. on May 28 at Keio University’s Tsunamachi Grounds, with the practice lasting for 1 hour and 30 minutes. Second baseman Cass hit a succession of home runs to left field and left fielder Halm hit “a fire-breathing home run like a powerful cannon” with a long shot to right field.25 In defensive practice, the players threw the ball with machine-like accuracy, catching even difficult throws. Although they had not yet shown their full potential, the Stanford players were praised as “the epitome of the American national sport.”26

The players’ track records were good as well, and as a team they were the strongest since the Stanford University baseball team was founded. They were said to be among the best teams on the West Coast, having won four times and lost once against Santa Clara University, which had previously defeated the Waseda University baseball club, 10-2. The cleanup hitter was Louis Cass, and the ace pitcher was Ray Maple, a side- arm thrower. Maple, first baseman Tom Workman, and shortstop Zeb Terry had such a high level of skill that they had been invited to join professional clubs. Maple turned down an offer to join the Philadelphia Athletics, Walkman received an offer from the Boston Red Sox, and Terry was invited to join the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League and later had a seven-year major league career.27

Given this context, it was thought that Keio, Meiji, and the Tomon Club, which consisted of graduates of the Waseda University baseball club, would not be able to compete with the Stanford team.28 In fact, the Stanford team did not perform as well as its track record would have suggested.

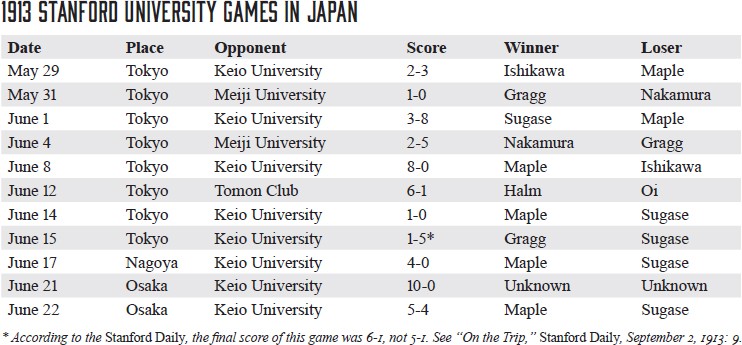

The Americans played eight games in Tokyo: a five-game series against Keio, two games against Meiji University, and a game against Tomon. Then Stanford and Keio traveled together and played in Nagoya and Osaka. They did not play against Waseda because their schedules were incompatible.

The series with Keio began at the university’s Tsunamachi Grounds in the Mita section of Tokyo on May 29. Maple took the mound for Stanford but Keio elected to start Shinryo Ishikawa, their second-string pitcher, to measure the visitors’ ability. The Cardinals jumped out to a 2-0 lead in the second inning, but Ishikawa remained steadfast and shut out the Americans for the remainder of the afternoon. Meanwhile, Maple limited Keio to just three hits and a single run as Stanford held a 2-1 lead going into the ninth inning.

Maples began the ninth by walking first baseman Shoji Goto, who was lifted for pinch-runner Daisuke Miyake. After a strikeout, Shigeru Takahama singled to right field, where Heinie Beeger bobbled the ball, allowing the runners to advance to second and third. With the tying and winning runs in scoring position, Shungo Abe strode to the plate. On the next pitch, Miyake broke toward the plate as Abe swung and missed. Caught in a rundown between third and home, Miyake scampered back to third, beating the throw, but his momentum carried him over the base. With Miyake’s feet off the bag, McCloskey applied the tag and then threw to shortstop Terry and he tagged out Takahama, who had strayed off second. Sure of the inning-ending double play, Terry dropped the ball near the mound and the Cardinals walked off the field. Seconds later, Miyake trotted home and stepped on the plate. After a brief conference, the umpire ruled that Miyake had been safe at third and his run counted. Without a loud protest, the Stanford players returned to their positions and recorded the final out. The 2-2 deadlock continued until the top of the 12th inning when a hit batsman, a force out, a stolen base, and a single gave Keio a run and the 3-2 victory.29

After the game, reporters and fans condemned both the umpires and the Keio players for taking advantage of the obvious missed call.30 The Stanford team’s attitude was praised thusly, “It is a mark of their generosity that, by the grace of the American gentlemanly temperament, Miyake was allowed to carry on without their contesting the decision.”31

On the last day of May Stanford sent A1 Gragg to the mound against Shunichi Nakamura and his Meiji University teammates. The two pitchers were nearly untouchable: Gragg surrendered just three hits and a walk while Nakamura held the Cardinals to a single hit and a base on balls. The score was 0-0 when Argabrite led off the top of the ninth with a bunt single. As Argabrite broke for second, Workman laid down a bunt between first base and the mound. Nakamura fielded it but his throw glanced off Workman, and as first baseman Takase retrieved the ball, Argabrite raced around the bases to score the winning run.32

After opening game, Keio pounded Stanford in their second meeting. “The American nine was so completely smashed,” wrote the Japan Times, “that it was a painful task to find and gather up the fragments that lay scattered round … [the diamond].” Keio batters managed only four walks and six hits off Maple, but four of the hits were doubles and the porous Stanford defense committed seven errors as the Japanese scored eight runs. Kazuma Sugase, the tall, bespectacled Keio captain, “shone brighter than the aurora borealis on the mound and with the ash” as he held the Cardinals to three runs on five hits and went 2 for 3 with two doubles and two runs scored at the plate.33 The magazine Yakyukai praised the outcome as “a superb victory for the Mita army.”34

The rout continued in the second game against Meiji. “Meiji Slaughters Stanford,” the Japan Times headlined its report. A hard rain left the diamond in poor condition and the “muddy and slippery ground made it difficult for the infielders, and incidental fun was provided more than once. When a runner slid into a base, he generally got up with a thick coating [of] mud.”35 Gragg took the mound for Stanford but Meiji found him “an easy proposition and got to him fast and furious,” as it cruised to a 5-2 victory.36

After consecutive blowouts, the reporter for the Japan Times wrote, “With his heart down in his boots and with a trembling hand, the scribe pens his obituary on the passing of the Cardinals.”37 But the writer had dismissed the visiting Americans too quickly. On June 8 they stormed back in the third game against Keio. Perhaps overconfident, Keio put Ishikawa instead of Sugase on the mound and “like a wounded and frenzied tiger, the Cardinals turned on the Keio gladiators with a snarl and deadly ferocity, and chewed them up.”38 As Maple was no-hitting Keio through the first eight innings, Stanford scored single runs in the third and fifth before breaking the game open with six runs in the seventh. In the bottom of the ninth, Miyake and then Goto singled to foil Maple’s no-hit game, but neither scored as Stanford won 8-0.

Keio’s boisterous fans took their frustrations out on the umpire, Lieutenant Burnett of the American Embassy. According to the Japan Times:

Many of his decisions on balls and strikes were strongly protested from the bleachers and grandstand. In addition, he made a few close decisions on bases and at the plate. … The howls of protest from the bleachers developed into a united uproarious denunciation of the arbiter. Jeering cheers and ovations were given him every now and again. Immediately after the game, the Keio players went and shook hands with Lieutenant Burnett one by one. …

While Lieutenant Burnett was shaking hands, a large crowd of unthankful and enraged fans rushed about him from all directions to mob him. A policeman, Keio professors, and Keio and Stanford players with baseball bats straightaway stood guard round Mr. Burnett. The threatening mob rapidly gained in size every second. The mob was highly worked up and would have struck at nothing. “Kill him!—Eat him up!” Hysterical outbursts of indignation were uttered repeatedly to stir the mob. Nothing could have stopped the excited mob, but for the appeasing, even appealing, efforts of Keio professors and students.39

As expected, Stanford had little trouble with the Waseda alumni team, the Tomon Club, on June 12.40 The Tomon Club’s lineup included future Japanese Hall of Famers Shin Hashido, Kiyoshi Oshikawa, and Chujun Tobita as well as Goro Mikami, who a few months later left for the United States to play for Knox College in Illinois and later for the professional All Nations barnstorming team. But with the exception of Mikami, these great players were past their prime. The former stars played a sloppy game, committing 11 errors and walking six batters, as Stanford won 6-1.41

On June 14 Maple once again took the mound for the Cardinals, but this time Keio countered with its ace, Sugase. According to the Japan Times, the two “fought for all they were worth. … Where Maple had speed, Sugase had curves; where one had mystifying floaters; the other had nasty underhand smokers; where one had the name of the best pitcher Stanford ever had, the other was cracked up to be the most clever and heady slabster that ever honored the Japanese diamond.”42 For seven innings the aces matched each other. Maple allowed just one hit, Sugase just two. Neither walked a batter nor allowed a run. But in the top of the eighth, Sugase hit Arthur Halm with an inside curve. Weak-hitting Pete McCloskey then slashed a single between third and short, moving Halm to third. A fly ball by Maple scored Halm and won the game, 1-0. The Stanford victory evened the series at two wins apiece and set up a game 5 showdown on the following afternoon.

Despite pitching a complete game the day before, Sugase took the mound again for Keio in the final matchup. Stanford rested Maple and countered with Gragg. Once again, the Japanese hit Gragg hard. Keio began the game with back-to-back doubles by Kenichi Kakeyama and Miyake, followed by an RBI single by Goto and another double by Akira Kusaka. Goto and Kusaka were left on base but Keio added two more runs in the fourth and another in the fifth to build a 5-0 lead. Meanwhile, Sugase “stood on the mound as firmly as Fuji-yama and showed himself as formidable and impregnable as a Dreadnought. His delivery was the goods of smoky, fast breaking, and hypnotic brand.”43 The Cardinals scored a lone run in the ninth as Sugase cruised to a 5-1 victory to capture the series.

The two teams next traveled west for a three-game series with a match in Nagoya and two in Osaka. Away from Tokyo, Stanford dominated Keio, winning 4-0 on June 17 in Nagoya, romping, 10-0, on June 21 in Osaka, and finishing the sweep with a 5-4 victory the following day as 25,000 watched in Osaka. On June 28 the Stanford Cardinals boarded the ocean liner Nippon and after a rousing sendoff by the Keio ballplayers, headed for Hawaii.44 Stanford stayed in Honolulu for about three weeks, winning six of the nine games against the U.S. All-Service team, the Punahou School, alumni from the St. Louis School and the Portuguese Athletic Club.45

Although the Cardinals ended their tour of Japan with a 6-4 record, their losses disappointed their hosts. We may ask why the Stanford team did not live up to expectations in Japan. As we have already seen, one of the major reasons may have been poor management of the team’s physical condition during their long voyage to Japan. Other reasons may have included poor field conditions and being insufficiently prepared for the environment—games were postponed by rain, indicating that the ground was still muddy when the games were played. Their performance may have been impacted by the fact that Maple, their ace pitcher, did not pitch as well as expected by someone who was being invited into the world of professional baseball.46 Furthermore, their second pitcher, Gragg, was not effective, losing twice.

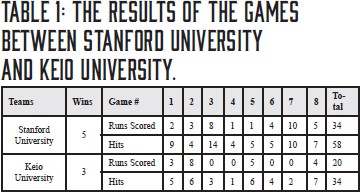

Overall Stanford outhit and outscored Keio. Stanford recorded 58 hits and 34 runs in eight games against Keio, 24 more hits and 14 more runs than Keio (Table 1). Stanford won five games; Keio won three. Therefore, although Stanford had the upper hand over Keio in terms of batting power, they appear to have been close in terms of overall strength including pitching and defensive ability.

Although the Stanford team drew significant attention upon its arrival in Japan, the newspaper coverage dwindled as the team moved through the games with each university, with articles reporting their return to the United States appearing only in the bottom comer of the paper.47

The situation was the same back at Stanford University. Certainly, the Stanford Daily printed a group photo of the Stanford and Keio players with the caption “In the Land of the Chrysanthemum,” and an explanation that the team had gone to a place 6,000 miles away from their homeland, played baseball with Japanese universities, and enjoyed Japanese culture including visiting the ancient city of Kyoto. However, compared with the detail provided when the team set off on its trip, there was little coverage after it returned from a tour in which it was victorious but not overwhelmingly so.48

In Japan, the Stanford team was criticized. “At first we had high expectations for them and were greatly disappointed,” alluding to the Japanese proverb, “When I actually see Mt. Fuji, it is lower than I had heard.” Stanford’s points to be commended were only two: Terry’s defense, baserunning, and captaincy, and Maple’s control of the slow ball.49 The evaluations—“they were not too bad” and “the Stanford team had better hitting, so Keio, which had a better battery but inferior hitting, was defeated finally”—also suggest the disappointment in Japan with the large difference between the visitors’ prior reputation and the actual results of the games.50

Does this mean that Stanford University’s trip to Japan in 1913 was a fruitless endeavor? If we focus solely on games won and lost, the Stanford team failed to achieve its intended purpose in the sense that it did not win a resounding victory against the developing Japanese student baseball teams. However, from the perspective of promoting friendship and goodwill between Japan and the United States through baseball, the trip was of great value. Zeb Terry, who began his seven-year major-league career with the Chicago White Sox in 1916 and is considered “one of the greatest baseball players in Stanford history,” considered the trip to Japan a “treasured” memory.51 Terry and the Stanford players were overwhelmed by the VIP treatment by the Japanese.52

The Stanford team visited various places around Tokyo between games. On June 5 they saw a performance of Kanadehon Chushingura at the Kabuki-za Theater and paid a courtesy visit to the legendary kabuki actor Onoe Kikugoro VI, who was known to be a baseball enthusiast. In addition, on June 6, at the invitation of the Imperial Theater, the team accompanied the Keio players to performances of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, Puccini’s opera Tosca, as well as a performance of the kabuki play Terutora Haizen by Chikamatsu Monzaemon starring Matsumoto Koshiro VII. On the day of the performance, Sada Yacco, who had starred in Tosca, presented handheld fans as souvenirs to the players of both universities, and the Stanford team presented her with a bouquet in return. These events can be seen as a sign of goodwill between Japan and the United States outside the stadium.53

Thereafter, at a reception held at the Kojunsha Club on June 2 for the Stanford and Keio players, manager Wilcox said on behalf of the American team: “We are delighted that our visit to Japan on this occasion has given us the opportunity to truly learn about Japanese customs and culture, and we hope that gathering together players from both universities will contribute to the friendship between Japan and the United States both today and in the future.”54 These words indicate that, from the perspective of US-Japan relations, the Stanford team’s visit to Japan went beyond baseball games, also serving as a platform for exchange for the young representatives of both Japan and the United States.

DR. YUSUKE SUZUMURA, bom in 1976, received a doctoral degree from Hosei University (Tokyo) in 2008, and is an associate professor of Meijo University (Nagoya), a visiting researcher of both the Hosei University Research Center for International Japanese Studies and the Hosei University Research Center for Edo-Tokyo Studies. He published the newest book Relationship between Religion of Philosophy and Society in Kiyozawa Manshi from Hosei University Press in February 2022. His majors are comparative philosophy, history of politics, and cross-cultural studies, and in recent years he has appeared on TV, radio, and internet media as a commentator. He is also a specialist in baseball history and has published three books since 2005. He serves as the president of the Forum for Researchers of Baseball Culture, co-executive director and an Editorial Board Member of the Japan Society for Intercultural Studies, and a member of the Society for American Baseball Research.

NOTES

1 Gantetsu Hashido, “A Team Which Has a Close Relationship with Japan,” Yakyukai, 3(8), 1913: 2-3.

2 Sheng-Lung Lin, Samurai Baseball Culture in Taiwan During the Period of Japan’s Colonization, Waseda University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2012, 102-103.

3 Hashido.

4 “Keio University Invites Stanford University,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, April 1, 1913: 5.

5 Hashido.

6 Masao Shimakura, “A Study of the Pacific Line as the Stage of Ship’s Band: A History of the Development from Meiji to Early Showa Eras,” Abstracts of the 2017 Annual Meeting, The Human Geographical Society of Japan, 108-10; “Stanford Has Come,” Yomiuri , May 27, 1913: 3.

7 “Cardinal Ball Players Sail for Land of Mikado,” Stanford Daily, May 19, 1913: 16.

8 “Cardinal Ball Players Sail for Land of Mikado.”

9 Yuichi Yoshino, “How Much Is Old ‘One Yen’ Today?” Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Cooperation, October 7, 2020, https://magazine.tr.mufg.jp/90326 (accessed on February 6, 2022).

10 “Eleven Men Sail for Japan Saturday Noon,” Stanford , May 7, 1913: 4.

11 “Declaration of Victory,” Yomiuri Shimbun, May 28, 1913: 3.

12 “Stanford Sends a Hummer,” Japan Times, May 28, 1913: 1.

13 “The Arrival of the Players of Stanford University,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, May 28, 1913: 5.

14 “Declaration of Victory.”

15 “Declaration of Victory.”

16 “The Schedule of Games Against the All Philippines Baseball Team,” Yomiuri Shimbun, May 5, 1913: 3.

17 “Final Score: Yokohama Commercial School 6, All Philippines Baseball Team 4,” Tokyo Asahi Shim, June 1, 1913: 5.

18 “The Arrival of the Players of the All Philippines Baseball Team,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, May 12, 1913: 5.

19 “The Arrival of the Players of the All Philippines Baseball Team.”

20 “The Arrival of the Players of Stanford University.”

21 Koichi Shibukawa, “The Fishes of Shizuoka: A History of Fish-Fauna Research and Some Future Perspectives,” in Yoshinori Yasuda and Mark J. Hudson, eds., Multidisciplinary Studies of the Environment and Civilization: Japanese Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2017), 17-18.

22 “Dr. Jordan’s View Against the Issue Concerning with Japanese People,” Yomiuri Shimbun, February 8, 1907: 2.

23 “The Great Ambassador of the Peace Has Come,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, August 27, 1911: 5.

24 “Declaration of Victory.”

25 “How Did the Players of Stanford University Practice?” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, May 29, 1913: 5.

26 “How Did the Players of Stanford University Practice?”

27 “Declaration of Victory,” “Stanford Sends a Hummer.”

28 Hashido.

29 “Keio Beats Stanford Boys,” Japan Times, May 30, 1913: 1.

30 “The First Game Against Keio University,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 28-29.

31 “The Baseball Games between Japan and the USA (The First Day),” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, May 30, 1913: 5.

32 “Stanford Wins Close Game,” Japan Times, June 1, 1913: 1.

33 “Keio Klouts Kalifornia,” Japan Times, June 3, 1913: 1.

34 “The Second Game Against Keio University,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 35-36.

35 “Meiji Slaughters Stanford,” Japan Times, June 5, 1913: 1.

36 “Meiji Slaughters Stanford.”

37 “Meiji Slaughters Stanford.”

38 “Stanford Defeats Keio,” Japan Times, June 10, 1913: 1.

39 “Stanford Defeats Keio.”

40 “The Game Against the Tomon Club,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 45.

41 “California Beats Tomon,” Japan , June 13, 1913: 1.

42 “Stanford Defeats Keio,” Japan Times, June 15, 1913: 1.

43 “‘Assimilate’ B.B. All Right,” Japan Times, June 17, 1913: 1.

44 “Stanford B.B. Boys Happy,” Japan Times, June 29, 1913: 8.

45 “On the Trip,” Stanford Daily, September 2, 1913: 9.

46 “Review of the Games against Stanford University,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 88-89.

47 “The Last Win of the Stanford University Team,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, June 28, 1913: 5.

48 “Stanford Ball Team Wins Majority of Games in Orient,” Stanford Daily, September 1, 1913: 1.

49 Taguchi Oson, “We Overestimated Them a Little,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 8.

50 Koyama Mango, “They Were Not Too Bad,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 7-8.

51 Don Liebendorfer, The Color of Life Is Red: A History of Stanford Athletics, 1892-1972 (Palo Alto: National Press, 1972), 230; Niall Adler, “Zeb Terry,” Society for American Baseball Research, BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/zeb-terry/ (accessed on April 10, 2022).

52 Adler.

53 “Visit to the Imperial Theater,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8 (1913): 95.

54 “The Stanford University Baseball Team’s Movements,” Yakyukai 3, no. 8(1913): 93-94.