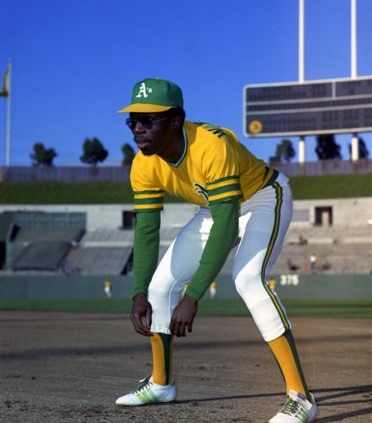

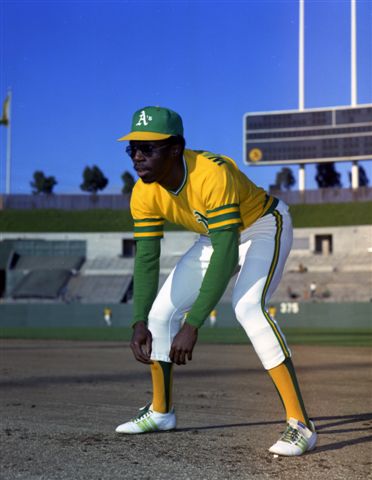

Designated Runner: Herb Washington

This article was written by Peter Warren

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

Herb Washington went to Michigan State for track and became a track star. But who would have thought he would become a baseball legend?

Washington was born on November 16, 1951, in Belzonia, Mississippi, but moved to Flint, Michigan when he was less than one year old. Washington and his family moved so his parents could work in the auto plants.[fn]“Herb Washington: World Record Sprinter & Business Success, ” MSU Spartans Alumni website, 19 February 2007, accessed 1 August 2011, www.msuspartans.com/genrel/021907aac.html.[/fn] He started high school at Flint Northern, but was ruled ineligible to compete in track and field because of a school district boundary dispute. After 10th grade, he transferred to Flint Central High School so that he could compete. At Flint Central he met the track coach, Carl Krieger, who helped Washington become one of the greatest runners in the world. “Coach Krieger had a vision and got me to believe,” Washington would later say. “He said the only thing holding me back was me.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

After receiving many scholarship offers in both track and football, “Hurricane Herb” chose Michigan State, where he ran track and field for the Spartans 1969–1972. In one of his races as a freshman, after leading most of the race, he lost to John Carlos, a member of the 1968 United States Olympic team infamous for their Black Power Salute. As a sophomore he beat Carlos at the 47th Michigan State Relays. After that, he was known as a better short distance runner than Carlos. By the time Washington graduated he had won one NCAA title, seven Big Ten titles, was a four time NCAA All-American, and had set world records in the 50-yard and 60-yard dashes.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

After receiving many scholarship offers in both track and football, “Hurricane Herb” chose Michigan State, where he ran track and field for the Spartans 1969–1972. In one of his races as a freshman, after leading most of the race, he lost to John Carlos, a member of the 1968 United States Olympic team infamous for their Black Power Salute. As a sophomore he beat Carlos at the 47th Michigan State Relays. After that, he was known as a better short distance runner than Carlos. By the time Washington graduated he had won one NCAA title, seven Big Ten titles, was a four time NCAA All-American, and had set world records in the 50-yard and 60-yard dashes.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

He was drafted by the NFL Baltimore Colts but it wasn’t the right job for Washington. Instead he took a job broadcasting sports for Channel 6 in Lansing, Michigan. It was there, in January 1974, when he got a message he did not expect—from Charlie Finley.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Charles Oscar Finley bought the Kansas City Athletics in 1960 and moved the team to Oakland in 1968. He was one of the most colorful baseball owners in history. His legendary stunts included Charlie O (a mule mascot) and green and gold uniforms that were visible from a mile away. He was an outspoken supporter of the newfangled DH rule. The year was 1974 and he was about to make another memorable move.[fn]Nick Acocella, “Finley entertained and engaged,” ESPN.com, Accessed 1 August 2011, http://espn.go.com/classic/biography/s/Finley_Charles.html.[/fn]

Washington received a message from Finley and the Athletics wondering if he wanted to play for them. He thought it was a joke. He hadn’t played organized baseball since junior high. Then he got paged by the A’s. It was no joke. Finley told Washington, “Herbie, I want you to play and be a pinch runner.”[fn]MSUSpartans.com[/fn]

The four time All-American decided the idea was worthwhile. The contract negotiations were rough. Washington wanted a no-cut contract. Finley was in shock. He told Washington that a no-cut contract was for players like Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, and Reggie Jackson. Washington replied by saying, “They can’t out-run me!” After holding out for a while, Washington got the contract he wanted. A one year, no-cut contract for $45,000 with a signing bonus of $20,000. Included in the contract was a clause that required him to grow a mustache before Opening Day. Washington, however, couldn’t grow one little hair. To get the $2,500 bonus that came with growing it, he used an eyebrow pencil to draw a believable mustache and got the bonus.[fn]MSUSpartans.com[/fn] He also got a base-running tutor in former base-stealing champ, Maury Wills.[fn]Franz Lidz, “Whatever Happened To… Herb Washington,” Sports Illustrated, Volume 79 Issue 3 (1993), 86.[/fn]

Not everyone was as sure as Finley that Washington would be able to make a contribution to the team. “He’s a great athlete, but he’s not a baseball player,” said future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson at the time.[fn]Eric Prewitt, “Herb Washington On Waivers,” The Portsmouth Journal, (1975), 12.[/fn] Washington’s career as “designated runner” got off to a shaky start. Not only was he unsuccessful in four of his first five attempts, he was also blamed for Oakland’s poor start. A’s pitcher Catfish Hunter set the critics straight: “There has been a lot of talk about Herbie, but he don’t hit and he don’t pitch, so it ain’t him.”[fn]Lidz, Sports Illustrated.[/fn]

For the rest of the season, both Washington and Oakland rolled. He ended up playing in 92 games, stole 29 bases, and scored 29 runs.[fn]“Herb Washington”, Baseball-reference.com[/fn] During one stretch he went 16 for 19.[fn]Lidz, Sports Illustrated.[/fn] Oakland, led by Cy Young winner Catfish Hunter (25–12), and by Vida Blue (17–15), Ken Holtzman (19–17), Rollie Fingers (9–5, 18 saves), and Reggie Jackson (.289, 29 HRs, 93 RBIs), ended the season with a record of 90–72.[fn]“1974 Oakland Athletics,” Baseball-Reference.com[/fn]

Herb Washington had many unusual moments. Even though he hadn’t played since junior high, he knew baseball. Once, Milwaukee Brewers first basemen George Scott told him he needed him to move so he could clean the base. Washington, having seen the ball in Scott’s glove, called time. Manager Alvin Dark once asked if he wanted to pinch-hit against Nolan Ryan. Washington said no, not because he was afraid to face the fireballing Ryan, but because he didn’t want to lose his uniqueness: a non-pitcher who had spent a whole season on a major league roster and yet had never once been to the plate.[fn]Lidz, Sports Illustrated.[/fn]

After winning the 1974 American League Championship Series three games to one against the Baltimore Orioles, the Athletics faced the Dodgers in the World Series. Finley set the bar high for Washington, saying, “He is going to rise and shine in the ’74 World Series.”[fn]“1974 Oakland Athletics,” Baseball-Reference.com[/fn] Finley was partially correct, Washington did become known.

The A’s won the first game. Then they were down by one run in the ninth inning of Game Two when Washington entered the game. Representing the tying run, Washington took his place at first base next to Dodgers NL MVP first baseman Steve Garvey, also a Michigan State alumnus. On the mound was another former Spartan, NL Cy Young Award winner Mike Marshall. Marshall actually taught both players at Michigan State.[fn]Lidz, Sports Illustrated.[/fn]

Everyone in Dodger Stadium knew what Washington was supposed to do: steal second base. The right-handed Marshall stepped off and threw over, and Washington got back easily. Then Marshall attempted to pick him off again and this time he stunned Washington. Washington dove back head first but he was too late; Garvey placed the tag. The NL MVP recalled the play: “He was frozen. We wanted to catch him flat-footed and we did.” Washington pounded the ground, saying “Damn!” The misstep gave the Oakland A’s little chance to win the game. But Washington did get his ring; Game Two was the only game the A’s lost as they won the Series 4–1. Washington appeared in three of the five games.[fn]Kevin Lamb, “Marshall’s Pickoff Ends Oakland Rally,” Milwaukee Journal (1974), 5.[/fn]

The next season came. The A’s were rolling when Finley cut the struggling Herb Washington on May 5, 1975.[fn]Ibid.[/fn] He had played in 13 games with only two steals that season. Said A’s team captain Sal Bando, “I’d feel sorry for him if he were a player.”[fn]Prewitt, The Portsmouth Journal.[/fn] [fn]Sarah Pileggi, “They Said It,” Sports Illustrated, Volume 42, Issue 20 (1975), 18.[/fn] His cumulative stats were 105 games, 31 steals, and 33 runs scored.

He was caught stealing 17 times (not a very good percentage for a base stealer). He had no plate appearances and never took a position in the field. Herb Washington’s baseball career was over.

Instead, he kept up his success in his business career. Washington is the owner of many McDonald’s restaurants in Pennsylvania and Ohio. He has held positions in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and he is active in many community organizations. Washington is married and is the father of two children.[fn]Eric Prewitt, “Herb Washington On Waivers,” The Portsmouth Journal, (1975), 12.[/fn], [fn]MSU alumni donations newsletter, Summer 2010, Accessed 1 August 2011, www.egr.msu.edu/files_egr/content/Developments_Summer2010-Consumers4-5.pdf.[/fn]

PETER WARREN is a 12-year-old, seventh-grade student from New Jersey. He has always been a fan of baseball. His interest in baseball history and statistics began when he was given a Baseball Statistics book at age six. He plays travel baseball and basketball in his hometown.