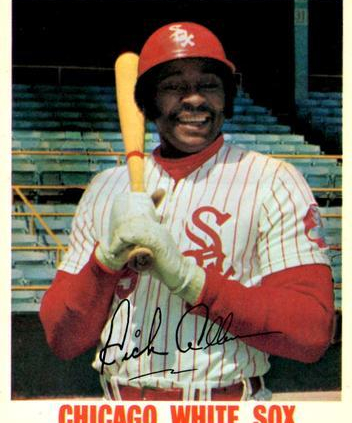

Dick Allen’s 1972: A Year to Remember

This article was written by Mark Lazarus

This article was published in The National Pastime: Classic Moments in Baseball History (1987)

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, Spring 1985 (Vol. 4, No. 1).

Richard Anthony Allen. Just the mention of his name evokes surprisingly emotional responses from the baseball fans who saw him play. Some recall Allen’s awesome natural talent, his intimidating presence on the field. Others regret his off-field difficulties, his seemingly wasted opportunity for greatness. When Allen burst onto the major league scene in 1964 as the National League’s Rookie of the Year, he had it all: He could run, hit for average and power, field, throw, and he had that unusual gift of awareness on the field, the “sixth sense” that enables great players to make the great play when it counts.

Richard Anthony Allen. Just the mention of his name evokes surprisingly emotional responses from the baseball fans who saw him play. Some recall Allen’s awesome natural talent, his intimidating presence on the field. Others regret his off-field difficulties, his seemingly wasted opportunity for greatness. When Allen burst onto the major league scene in 1964 as the National League’s Rookie of the Year, he had it all: He could run, hit for average and power, field, throw, and he had that unusual gift of awareness on the field, the “sixth sense” that enables great players to make the great play when it counts.

If natural ability were the criterion for Hall of Fame election, Allen would be a sure thing; instead, he is on the outside looking in and figures to stay there. Still, despite devastating injuries to his right shoulder, wrist, and hand, a succession of disputes with management, media, and fans, and a growing battle with alcohol, Allen still produced a .292 career average and blasted 351 homers. In 1976, Dick himself wondered, “The Lord gave me a talent, but only He knows how much. Imagine if! didn’t have this [pointing to his shoulder] and this [pointing to his hand]. Imagine what might have been.”

Nothing was left to the imagination in 1972. Dick Allen was not only the dominant player in baseball, but his impact on the game and the city of Chicago went beyond the confines of the diamond. The period 1972 to 1974 was known as the “Allen Era” on the South Side. The attendance figures bear that out:

- 1971: 833,891

- 1972: 1,177,318

- 1973: 1,302,527

- 1974: 1,149,596

- 1975: 750,802

Roland Hemond, general manager of the White Sox, still believes that Allen saved the American League franchise for Chicago. If it had not been for those three years, we might now have the Pale Hose of New Orleans, Denver, or Toronto. Beyond the raw attendance numbers, Allen’s popularity and his leadership of a mediocre team into contention brought the South Siders much needed publicity and media exposure. In 1972, the Sox games were broadcast on radio station WEAW-FM, a station that could barely be heard in the Loop. The following year, they contracted with WMAQ, a 50,000 watt AM station that could be heard clearly (at night) in Philadelphia!

In April of 1972 fans endured baseball’s first full-scale labor strike, forcing the cancellation of 85 games and creating an uneven schedule (one that in the end would frustrate Red Sox fans particularly, as Boston finished one-half game behind Detroit in the American League East). The ailing national pastime was in desperate need of a surprise team, an epic phenom, or the coming of age of a superstar. While Carlton Fisk did his best to fill the role of phenom (Rookie of the Year in the AL), and Steve Carlton rolled to a 27-10 Cy Young Award year with a last place team, it was Dick Allen and the Sox who captured hearts and headlines around the country.

In retrospect, it is amazing that the Sox were in the pennant race. Their main competition was an Oakland A’s team that was to win the first of their three straight World Championships. The Sox finished seventh in team batting (.238), eighth in ERA (3.12), and ninth in defense (.977). They outscored their opponents by only 28 runs (566-538), yet were twenty games over .500! Oakland outscored their opponents by 147 runs, but finished 29 games over .500. Using Bill James’ Pythagorean Method of determining a team’s won-lost record — (Runs2 / (Runs2 + Opponent’s Runs2)) = Won-Lost percentage — the Sox should have finished eighteen games behind the A’s, but were only five and a half behind when the season clock ran out. Chuck Tanner did a phenomenal job of managing, maximizing his team’s mediocre talents and winning the close games (evidenced by their 38-20 record in one-run decisions). The pitching staff was led by the big three of Wilbur Wood (24-17, 2.51 ERA), Stan Bahnsen (21-16, 3.60), and Tom Bradley (15-14, 2.98), who collectively started 130 of the 154 games. The ace of the bullpen was twenty-year-old southpaw Terry Forster (6-5, 2.25, with 29 saves); Goose Gossage, only six months older, was 8-1 but saved only 2 games.

The Sox leadoff men—Pat Kelly and Walt “No-Neck” Williams were platooned—hit a combined .257 and scored only 79 runs. Mike Andrews batted second and “ripped” AL pitching at a .220 clip and scored 58 runs. Bill Melton, the league’s home run champ in 1971 whose big bat was supposed to keep opponents from pitching around Allen, was shelved by a back injury in June and provided a meager 7 homers. His cleanup slot was taken by Carlos May, who hit .308 but certainly could not generate the power to protect Allen. May, in fact, went from July 23 to September 20 without a homer. The rest of the lineup was a collection of has-beens, never-will-be’s, and maybe-someday’s.

Despite being pitched around (Dick tied for tops in the AL with 99 walks), Allen still piled up some very impressive stats. As late as September 9, he led all categories for the Triple Crown. Rod Carew’s solid September edged Dick by .011 for the batting title, but Allen’s domination of all other offensive stats was awesome. His 37 home runs led the league; only one other player hit more than 26 (Bobby Murcer, 33). His 113 RBIs also set the pace by a wide margin; only one other had more than 96 (John Mayberry, 100). Allen’s margin in slugging percentage over Carlton Fisk (.603-.538) was the biggest since Frank Robinson’s Triple Crown in 1966. As further proof of Allen’s dominance, I offer Bill James’ Runs Created formula, computed for 1972. Taking into account steals, caught stealing, and bases on balls as well as hits and total bases, it is a superior measure of offensive contribution to either the batting average or the slugging percentage.

Top Five, Runs Created

- Allen, CHI: 128

- Murcer, NYY: 110

- Mayberry, KCR: 99

- Rudi, OAK: 98

- Fisk, BOS: 90

In the premiere issue of The National Pastime, Bob Carroll wrote a piece (“Nate Colbert’s Unknown RBI Record,” TNP 1982) detailing the group of players that drove in 20 percent of their team’s runs in a season. At 19.96 percent, Allen just missed that plateau in ’72. However, none of the eight “20 percenters” (Frank Howard did it twice) accomplished it in the pressure of a pennant race. Jim Gentile’s Orioles finished third in ’61, but fourteen games behind the M&M Yankees. Ernie Banks was the National League’s MVP in ’59, but the Cubs finished tied for fifth, thirteen games back. All of the others finished at least twenty and a half games out of first, with Wally Berger’s 1935 Braves finishing an astonishing sixty-one and a half out. Certainly the Braves would have finished last with or without Berger, but the 1972 Chicago White Sox were a different story.

The definition of Most Valuable Player was epitomized by Allen’s one-man gang. In addition to his prolific hitting, he stole 19 bases and finished second, only .0004 behind Mayberry, in fielding percentage. Coming down the stretch, in August and September, he hit .305 with an on-base average of .431. Despite their obvious intent to pitch around Dick, the World Champion A’s were ripped by Allen for an on-base average of .514 and a slugging percentage of .647!

The way to beat the Sox was to pitch around Allen in clutch situations. This was evident from his 53 walks in the 65 losses he played in, compared to 46 walks in the 83 wins. When granted the opportunity to swing the bat, Allen hit .343 in winning games, .265 in losses. And he loved to entertain the home folks. In old White Sox Park (as it was called in ’72), Allen hit 27 of his 37 HRs and had 83 of his 113 RBIs!

Some memorable moments of that memorable year:

- June 4: In the second game of a doubleheader against the Yankees, with two on and one out in the bottom of the ninth, Allen (pinch-hitting for Rick Morales) blasted a Sparky Lyle pitch into the upper deck in left for a dramatic 5-4 victory. I’ll never forget listening to Phil Rizzuto’s call on radio (on my way to a batting cage in Seaside Heights, NJ). All the Scooter could shout over the roar of the crowd was, “I don’t believe it!!! I don’t believe it!!!,” over and over, never telling what actually happened. It was at least two or three minutes before Frank Messer grabbed the microphone and told us of Allen’s blast! On the All Star game telecast that year, the network showed a replay of the homer. Roy White took one step back, then headed straight for the dugout. It was one of the few times that I ever saw Allen display emotion on the field. As he rounded first and realized the ball had disappeared in the upper deck, he pumped his right fist in the air in triumph. Of course, he was mobbed by his teammates at home plate. It was a great moment for Dick, the Sox, and all of his fans (but not for the three Yankee fans who were in the car with me!)

- July 31: Allen became the seventh player in history, and the only one since 1950, to hit two inside-the-park home runs in one game. The pitcher victimized by both homers was Bert Blyleven, and the center fielder who fell victim to Allen’s torrid line drives was Bobby Darwin. Dick connected in the first inning with two on, and in the fifth with one on to lead the Sox to an 8-1 victory.

- August 23: Allen became only the fourth player in history to reach the center field bleachers at Comiskey Park. Only Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg, and Alex Johnson before, and Richie Zisk since, have been able to reach the seats. Again, Allen’s was extra special. The blast came off Lindy McDaniel of the Yankees in the seventh inning with one on and cemented a 5-2 win to vault the Sox into first place. During the 1972 season, the Sox played all of their Wednesday home games in the daytime, and Harry Caray would broadcast from the center field bleachers, soaking up the sun and suds with his compatriots. Allen’s shot missed Caray by just a few rows. Unfortunately, I have never had the opportunity to hear Caray’s call of the homer, which must have been great. To reach the bleachers, the ball must travel 440 feet to the back wall and clear the sixteen-and-a-half-foot-high wall. Allen’s blast cleared the wall easily.

- September 7-12: In a seven-game stretch against West rivals Oakland, California, and Kansas City, Allen had 16 RBIs, including four game-winners!

In November Allen was named, to no one’s surprise, the AL Most Valuable Player. During the winter a new contract was negotiated, calling for $225,000 per year for three years, making Allen the highest paid player in the game at the time.

Dick was well on his way to another MVP caliber year in 1973 when he broke his leg in a collision with Mike Epstein in June. In retrospect, this event seemed to burst the bubble as the pressures of the media, management, and fans became too much for Allen to bear. Despite a triumphant return to action in 1974, in which he led the league in homers and slugging, Allen announced his retirement on September 14. Over the winter the Sox traded his rights to Atlanta, who subsequently dealt him to the Phillies in May of 1975. Although welcomed home warmly by fans in the city of brotherly boos, Allen’s continued erratic behavior and eroding skills led to his release after the ’76 season. Charley Finley gambled by signing Allen for ’77, but a quick exit from the ballpark during a game in June prompted his suspension and final release.

Dick Allen was a complex man with some deep-seated psychological scars that affected his behavior. But the sight of No. 15 digging in at the plate, tugging his uniform at the shoulders and left leg, pushing his batting helmet down on his afro, outlining the outside corner of the plate with his bat, and waving that forty-ounce war pole, brought a tremendous surge of excitement to the game. Wherever he played, the anticipation of a titanic home run had the crowd alive with each at-bat. In Philadelphia fans would not leave the ballpark until after Dick’s final at-bat of the game, no matter what the score. Dick Allen may not make it to the Hall of Fame, but he was a player with style, a uniquely fearsome batter who will be remembered not only for what he might have been, but also for what he was.