Dick Allen’s Second Act

This article was written by Mitchell Nathanson

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

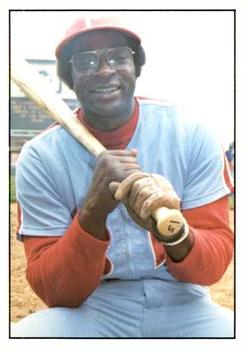

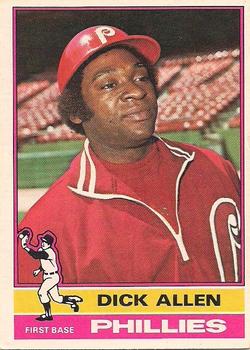

It is hard to imagine a more polarizing figure in Philadelphia sports history than Dick Allen. Countless gallons of ink have been spilled in furtherance of trying to capture and explain Allen’s stormy relationship with the Phillies and the city of Philadelphia during his 1963-69 tenure with the club. Much less focus has been given, however, to his mid-Seventies return to Philadelphia amid circumstances that were seemingly far different than those in which he left it. Despite these purportedly changed circumstances, Allen departed Philadelphia in 1976 much as he had in 1969 – amid controversy and bad blood on both sides of the equation.

It is hard to imagine a more polarizing figure in Philadelphia sports history than Dick Allen. Countless gallons of ink have been spilled in furtherance of trying to capture and explain Allen’s stormy relationship with the Phillies and the city of Philadelphia during his 1963-69 tenure with the club. Much less focus has been given, however, to his mid-Seventies return to Philadelphia amid circumstances that were seemingly far different than those in which he left it. Despite these purportedly changed circumstances, Allen departed Philadelphia in 1976 much as he had in 1969 – amid controversy and bad blood on both sides of the equation.

This article focuses on Allen’s return to the Phillies and his abbreviated tenure with a club that was building toward greatness. Whether Allen ultimately contributed toward, or detracted from that greatness remains, like so much else regarding Dick Allen and the Phillies, subject to debate.

The story begins on September 14, 1974, the date Allen announced his abrupt retirement from the Chicago White Sox despite the fact that at the time he was not only leading the American League in home runs (a title he’d retain at year’s end despite missing the final two weeks of the season), but a key element in the Sox’s divisional championship aspirations (they eventually finished the season nine games behind Oakland in the AL West).

In typical Allen fashion, his retirement was awash in contradictions: he arrived at the ballpark apparently prepared to play, suited up, took batting practice, and then announced his retirement. As for whether Allen’s by then well-chronicled difficulties with management were to blame, he claimed otherwise, having told his teammates just prior to his official announcement to the media that he’d “never been happier anywhere than here.”1 By most accounts, Allen’s statement was sincere – the White Sox appeared to have been an ideal place for him, with his easygoing manager, Chuck Tanner, giving him the room he needed to blossom at last. And blossom he did, winning the 1972 AL MVP award and developing, before a hairline fracture of his left leg in June 1973 sidelined him, into one of the best all-around players in the game.

Fully recovered from that injury in 1974 and, at 31, in the prime of his career, Allen picked up where he left off – he was hitting .301 with 88 RBI’s to go along with his league leading 32 home runs at the time of his unexpected announcement. However, his body had been breaking down in other respects – a nagging shoulder injury hounded him all season and by September, the pain was radiating down his back.2 Within weeks of his retirement, however, Allen had modified his stance with regard to his future in baseball, claiming that he was “gonna play somewhere next year – even if it’s Jenkintown.”3

This was all some in the Phillies organization as well as the Philadelphia sports media needed to hear. With Allen looking for a place to play, many Philadelphians began to ask the question few would have dared to ask only a few years earlier: “Why not here?”

The question made sense in many ways. For the 1974 Phillies bore little resemblance to the squad, either on the field or in the front office, which Allen departed amid so much rancor only five years earlier. Having abandoned crumbling Connie Mack Stadium as well as the racially divided North Philly neighborhood that seemed to provide a microcosm of everything wrong with both the city and the club, for the clean, spacious Vet (located, not by accident, in a South Philly warehouse district that was largely liberated from the city’s grid and all of the squabbles that were perceived to have emanated from it) in 1971, the Phillies were, in many ways, starting fresh despite their deep roots within the city.4 Parking was plentiful, the team was young and exciting, led by rising stars such as Greg Luzinski, Mike Schmidt, Larry Bowa, and Dave Cash, and management was likewise young and enthusiastic, with Ruly Carpenter having taken over the reins from his father Bob, whose relationship with Allen during his initial tenure with the club was complicated to say the least. Along with general manager Paul Owens and manager Danny Ozark, the new Phillies bore little if any resemblance to the old ones in so many ways. If they could fix all that had been so wrong with the franchise for so many years, why could they not repair their relationship with Allen as well?

Beyond the redemptive aspect to Allen’s return, his presence in the club’s lineup seemed to make sense in more practical ways. In 1974 the organization’s surplus of young talent finally began to mature and the Phils, cellar-dwellers for so long, managed to tickle the pennant-chase fancy of the Philadelphia sporting public for the first few months of the season until Luzinski was lost to a severe leg injury in June. Adding Allen’s bat to the lineup would provide insurance for 1975 should the team suffer another major injury. In addition, it would give the ’75 Phillies lineup the presence of both the 1974 American as well as National League home run champs (Schmidt won the NL title with 36). Add in the “Yes We Can” enthusiasm of second baseman Dave Cash, the fielding and fire of Larry Bowa, the steady hand of catcher Bob Boone and the mastery of pitcher Steve Carlton, and the Phillies would no doubt be in the postseason conversation all year long.

First, however, Allen had to be convinced to put aside his reservations and agree to suit up once again for the club he once so despised that he signaled his displeasure through messages such as “Boo” and “Oct. 2” (the last day of the 1969 season and, he hoped, his final day as a Phillie) scratched in the dirt for all to see.5 That he would be willing to play, as he said, in Jenkintown for the 1975 season did not necessarily mean that he would just as willingly play a few miles away in South Philly for the Phils.

Initially, the leading proponent for Allen’s return was Phillies’ broadcaster Richie Ashburn, who repeatedly lobbied for the Phils to re-sign him in his Evening Bulletin columns.6 Eventually Ashburn caught the ear of the front office who thought enough of the idea to organize a clandestine visit (to circumvent tampering charges) to Allen on his Bucks County farm to gauge his interest and to encourage him to consider the possibility.7 Specifically, Ashburn, Schmidt, and Cash made the “secret” trek in February 1975, and were outed in the media almost immediately. By that time, Allen’s rights had been purchased by the Braves who were unsure what to do with him after he announced that he’d never play in Atlanta.8

Despite Allen’s protestations, given that he was the property of the Braves, the Phillies’ secret mission quickly erupted into controversy, compelling the club to respond to the Braves’ tampering allegations. Nevertheless, Dave Cash, who by that point had become the team’s de facto leader, came away from the meeting impressed with Allen and, despite Allen’s departure from Chicago and his refusal to play for Atlanta, convinced that Allen would not disrupt the young team’s cohesive chemistry.9 However, Cash seemed to be one of the dwindling few in baseball who still believed in Allen.

As spring training began and Allen remained on his farm, his list of potential suitors grew shorter and shorter. The Cardinals, for whom Allen played after his trade from Philadelphia, passed, with third baseman Joe Torre stating that he believed that the Cardinals’ reluctance to sign Allen had much to do with ownership’s belief that he would disrupt the team over the long haul.10 In New York, Mets manager Yogi Berra tamped down speculation immediately, announcing that he wanted no part of Allen even if the Mets could obtain him without surrendering any players.11

Only in Philadelphia was the prevailing mood different. First baseman Willie Montanez, who would be displaced should Allen sign, stated that he’d gladly move to the outfield for Allen12; Schmidt announced that he did not see how Allen could do anything other than help the team win the NL East in 1975 and could not imagine a scenario where he would be disruptive; other players echoed similar sentiments.13 While Luzinski remained, at least outwardly, hesitant, his voice was in the clear minority.14

Regardless, with spring training winding down and the Allen issue no closer to resolution, the Phillies “officially” ended their pursuit when they announced that they were unable to work out a deal with Atlanta to obtain his rights. Conspicuously silent was manager Danny Ozark, who was said to be pleased with an end of the courtship. No doubt aware of the perception of Allen’s effect on previous managers in Philadelphia, Ozark was relieved his fate would sink into the abyss some allege swallowed Gene Mauch and Bob Skinner. Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson wrote, in an article headlined “That Was a Smile on Ozark’s Face,” he would finally have a realistic shot at completing the new two-year extension he signed in 1974.15

Regardless, with spring training winding down and the Allen issue no closer to resolution, the Phillies “officially” ended their pursuit when they announced that they were unable to work out a deal with Atlanta to obtain his rights. Conspicuously silent was manager Danny Ozark, who was said to be pleased with an end of the courtship. No doubt aware of the perception of Allen’s effect on previous managers in Philadelphia, Ozark was relieved his fate would sink into the abyss some allege swallowed Gene Mauch and Bob Skinner. Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson wrote, in an article headlined “That Was a Smile on Ozark’s Face,” he would finally have a realistic shot at completing the new two-year extension he signed in 1974.15

When the Phillies withdrew their courtship, Allen stoked the cooling embers, announcing to those members of the media who had followed him to one of his favorite haunts, Keystone Race Track, that he was “available and I want to play baseball.”16 He stated he was in “great shape” and “could be available to play in five days to a week.” Finally, in April, the Phillies forced the Braves’ hand when they put in a claim for Allen when Atlanta placed him on waivers. The Braves withdrew his name from the waiver wire and negotiated with the Phillies for his rights.

On May 7th, the Phillies announced that they had signed Allen to a contract. Right away, Cash exhorted Philadelphia fans to “give him a chance” when he arrived in uniform.17 Very quickly, it was clear that the overwhelming majority of them were willing to do that and more. He was greeted by cheering fans while warming up before his first game and then, during the pregame introductions, received a standing ovation as soon as he was introduced. The cheers continued as PA announcer Dan Baker tried in vain to resume announcing the Phillies starters that evening. Eventually he gave up.18 After the game Allen was beaming, stating that the cheers had affected him in a profound way: “You don’t know what it means to me,” he said. “It’s a different situation altogether.”19 He said that he believed that, this time around, baseball in Philadelphia would be nothing but fun for him. This would turn out to be an overly-optimistic prediction.

The long layoff and the lack of spring training affected Allen more than he anticipated. By July he was hitting only .233 with only four home runs in 50 games. Hopes that he would eventually round into form were dashed by July when his average slipped into the .220s and he managed only one home run in the month. Defensively, age and injuries appeared to be catching up with him at last as he lacked the range and finesse of Montanez; the entire infield struggled due to Allen’s inability to dig balls out of the dirt. Larry Bowa was the most directly affected by Allen’s struggles and, true to form, the one who protested most loudly as well, although even he tried to keep his public statements in check. When asked in early September why he had already amassed 22 errors – twice as many as in each of his five previous seasons in the majors, Bowa replied, “I’m not going to sound off. Knowledgeable people know what’s going on.”20

By season’s end, Allen was hitting .233 with all of twelve home runs and 62 RBI’s. Moreover, in just 416 official at-bats, he struck out 109 times. These were obviously not the numbers the Phillies had envisioned the previous winter when organizing their covert rendezvous at Allen’s farm. Regardless, the team as a whole did improve markedly from 1974, finishing second, 6.5 games behind the Pirates, completing their first winning season in eight years. Besides, this time, Allen’s troubles appeared to be solely of the on-field variety. With a full spring training to help him prepare for 1976, the Phillies hoped that Allen would return to form. Therefore, they re-signed him for the ’76 season, setting aside their doubts that perhaps he was finished as a ballplayer.21 Although the ’76 Phils would indeed succeed on the field as management hoped, they nevertheless endured a difficult season off of it, with Allen at the center of much of the controversy that erupted as the team headed towards its first postseason berth in over a quarter-century.

Despite having the benefit of a full spring training, Allen’s 1976 season began much the way his previous season ended. After only ten games, Ozark had come to the conclusion that the prospect of Allen at first on a daily basis was too much for the team to bear: he replaced him the next day with the defensively solid Tommy Hutton at first and thereafter Allen’s playing time began to wane. A few days later, after sitting yet again, Allen refused Ozark’s instruction to pinch hit in the ninth inning of a tight game against the Braves, forcing Ozark to scramble and call on Jerry Martin instead. After the game it became clear that now, Allen’s troubles had migrated from the field to the clubhouse. Ozark attempted to deflect the brewing storm by telling the media that Allen was “unable to play.”22 When reporters continued to press the issue Ozark attempted to clear the room. When that failed, he threatened to punch a reporter who questioned Ozark’s right to take such action. The exasperated Ozark then exited his office, slamming the door behind him and kicking the wall and waste paper basket on his way out. A few minutes later, Ruly Carpenter exchanged words with the same writer who had questioned Ozark earlier and then issued a more general epithet to the entire assembled press corps as he entered his elevator.23

Thereafter, Allen settled uneasily into a platoon with Bobby Tolan at first base with the organization and fan base waiting for his stroke to return. Although he did hit better for a while (even flirting with the .300 mark for a portion of the season) it was clear that he was no longer the hitter he had been just a couple of years earlier. When he was dropped to seventh in the batting order (at the time, he was hitting .250 with a lone double constituting his only extra-base hit of the season) he expressed his frustration with how he was being handled: “If I’m going to slow ‘em up that much I’d rather not be in there at all,” he said.24

Regardless, he received strong support all season. When he hit two home runs in a June rout of the Cardinals, he received a game-stopping ovation from the Veterans Stadium faithful. Afterwards he revealed just how much the ovation meant to him by stating that fan support in Philadelphia meant more to him than anywhere else “because of what went on before.”25 Still, his feelings for the Philadelphia fans would not be enough to stave off another confrontation between Allen and the Phillies front office.

This one began innocuously enough: on July 25th Allen was injured in a collision on the basepaths with Pirate pitcher John Candelaria. The next night he asked out of the lineup by telephoning Ozark and complaining of dizziness.26 Thereafter the seeds for the inevitable clash were sown: the following day he neither phoned anyone nor arrived at the stadium; the day after that he arrived, remained for three innings and then left mid-game without informing anyone of his departure; and the following day he neither phoned nor showed up for the game.

Finally Ozark had no choice but to call a team meeting to discuss Allen’s repeated absences. At that meeting, Ozark classified Allen as being AWOL and then called a press conference to announce that Allen would be fined for his repeated unexcused absences. However, in a reversal reminiscent of Allen’s first stay in Philadelphia, Ozark subsequently rescinded the fine when Allen showed up unexpectedly in New York. At that time, Ozark shifted gears by announcing that Allen was injured and would be placed on the disabled list despite the fact that he had yet to be examined by a physician.

His DL stint was scheduled to end on August 10th; on that date he called the team and insisted that he was still hurt, indicating, according to Inquirer columnist Bruce Keidan, that he had finally seen a doctor the day before – the first time he had seen one since his collision with Candelaria. This resulted in several additional weeks on the sidelines when Allen insisted that he was unable to play. Finally, on September 3rd, six weeks after the collision with Candelaria, Allen pronounced himself ready for action. When pressed into service, however, he struggled, going 3-for-40 during one September stretch. With the Phillies suddenly in the midst of a pennant race (having lost much of their once seemingly insurmountable lead and now struggling to stay ahead of the surging Pirates), and with Luzinski’s now chronically sore left knee bothering him again, Allen was unable to stanch the bleeding.

The locker room was devolving as well. In August Allen stated that he believed that Ozark’s outfield platoon was racially motivated. He questioned black players including Ollie Brown and Bobby Tolan not playing as often as their white counterparts, suggesting that the Phillies were “working a quota system.”27 By the time the Phillies finally righted themselves and clinched the Eastern Division, they were clearly and openly separated along racial lines – the communal spirit of Cash’s “Yes We Can” mantra having been replaced with spite and suspicion. As the team celebrated its divisional title in the cramped clubhouse of Montreal’s Jarry Park, Allen initially refused to join in, preferring to remain, alone, on the frigid bench.28 When he finally entered the clubhouse, the club’s racial division was presented for all to see: Allen, Cash, Maddox, and Mike Schmidt (whom Allen had taken under his wing) removed themselves from the rest of the club and celebrated in private, in a clubhouse broom closet.29 “The Broom Closet Incident,” as it came to be known, would haunt the team throughout its abbreviated postseason run.

When the team boarded the plane from Montreal to St. Louis, Allen was nowhere to be found. Later, he announced that he would not participate in the postseason either unless Tony Taylor – who had all but officially retired during the season, having only 26 plate appearances all year and by then serving as a de facto bench coach – was activated for postseason play.30 Although this ultimatum appeared to many to have come out of the blue, in fact Allen confided to a member of the black press back in July that he would demand as much if the team qualified for postseason play: “I remember when I was playing with the Phillies before and having a fantastic season. It was Tony who made it possible He always encouraged me and suggested things that would help me….If we get to the playoffs and I know we will…I think it’s only right that a guy like Tony that gave so much should be there.”31

Now, determined to ensure that the club properly acknowledge Taylor’s contributions to the organization over the course of his career, the postseason roster issue quickly progressed to a stalemate between the club and Allen. Hoping to head off a steamrolling player insurrection, Ozark then publicly granted Allen permission to go home rather than participate in the St. Louis series, even though Allen was already home.32 Ozark then called another team meeting wherein he asserted that nobody was going to dictate the club’s playoff roster to him. At this point, whispers of a postseason player boycott grew loud enough for the media to hear.

With the team headed for its first postseason series since 1950, the team was now openly feuding. Several black players questioned Ozark’s managerial moves, echoing Allen in wondering why the white Jerry Martin rather than the black Ollie Brown played in the second game of the doubleheader in Montreal, after the Phils had clinched the division in game one. They were unsatisfied with Ozark’s reply that Brown’s recent struggles had put him on the bench.33 White players voiced their anger and frustration with Allen and his decision to go home rather than accompany the team to St. Louis.34 The Broom Closet Incident was likewise rehashed, with Tug McGraw stating in a team meeting that “some of us white guys” were wondering “where all the black guys were.”35

As things continued to spin out of control, Garry Maddox responded to McGraw’s comment by taking offense to what he thought McGraw’s statement implied: “Either we had great unity on this team all year or it’s been a great acting job by the players keeping their feelings inside. … Now when all the racial stuff starts coming out, when guys start to say how they actually feel, then you know how it is. … I signed a five-year contract with this team. I hope I didn’t make a mistake.”36 Captaining the divided crew, Ozark was nevertheless adrift. He had considered quitting earlier in the season, during Allen’s initial absence from the club, but decided to hold on due to the Phils’ overwhelming divisional lead.37 Now, with the playoffs at hand, he had no choice: he had to somehow steer the ship regardless of the infighting.

Finally, on the eve of game one of the League Championship Series against Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine, the club was finally able to coax Allen back by promising that Taylor would be in uniform for the postseason, albeit as a coach and not as a player. Although Allen had previously insisted that Taylor be activated for the postseason, this time he stated that all he really wanted was for Taylor to be in uniform in some capacity and that he was happy with the brokered deal.38 With that, it seemed as if the Phillies could finally focus their attention solely on the Reds. Very quickly, however, they became sidetracked yet again.

During the series, Allen, still smarting from the cavalcade of incidents over the past couple of months, refused to participate in the team’s pregame batting practice (Allen, not unlike some other top players of his era such as Ernie Banks and Willie Mays, considered batting practice to be an unnecessary ritual and often skipped it. But as with all things Allen, when he skipped it, more was made of the occasion).39 Two of his broom closet brethren, Cash and Schmidt, then attempted to deflect attention from what they thought would be perceived by the media as yet another example of Allen’s defiance by refusing to take infield practice before each of the three games of the series.40 Not surprisingly, amid the heightened tension surrounding the club, the Phils were swept in the series and the once-hopeful 1976 season came to a sudden and disappointing end. Thereafter, Allen was informed that he would not be re-signed for the 1977 season and his second act drew to a close.

In assessing Allen’s mid-Seventies return to the Phillies, there are, like so many things associated with Allen, contradictions and opposing points of view. On the one hand, the team as a whole did indeed improve during each of his two seasons with the club – he joined a club coming off a third place, sub-.500 finish in 1974 and left one which won 101 games and the National League’s Eastern Division, reaching the postseason for the first time in over a quarter-century. On the other hand, disharmony and dissension trailed him throughout his return to Philadelphia as he was a key figure in the clubhouse issues that dogged the 1976 club – one that perhaps could have achieved even more than it did had it been free from such distractions and been able to focus more intently on the game on the field, particularly during the postseason.

However, it is fair to ask if Allen was the cause of the dissension that enveloped the ’76 club or merely responsible for bringing to the fore that which was already there. Just as the 2008 election of Barack Obama failed to make the United States a “post-racial” society overnight, it seems difficult to fathom that the historically racially-troubled Phillies transformed as dramatically as touted in the short time between Allen’s departure in 1969 and his return in 1975. Perhaps they had further to go in the department of race relations than many realized and it took Allen to bring that reality to the surface.

And then there was his impact on the young slugger Mike Schmidt. Allen took Schmidt under his wing in 1975 and Schmidt has frequently mentioned the pivotal role Allen played in his development. Schmidt followed Allen in many ways and to many places, including that Montreal broom closet. Whether Allen was ultimately a positive or negative force in Schmidt’s career is a topic that has been debated now for decades – did he help Schmidt develop into the Hall of Fame slugger he ultimately became? Or was he at least partly to blame for Schmidt’s career-long inability to become the cohesive team leader fans and the club wished him to be? Most likely, the answer lies somewhere between these two poles.

Bill James once described Allen as someone who “did more to keep his teams from winning than anybody else who ever played major league baseball.”41 On the surface, Allen’s actions down the stretch in 1976 might appear to at least suggest as much. But beneath it, when focusing on actions that hindered the club’s potential, one wonders if anything Allen might have done in ’76 could match the organization’s longstanding reluctance to embrace and encourage the development of black ballplayers in Philadelphia in the decades leading up to that season.

Viewed through this lens, perhaps the succession of events that transpired during the club’s ’76 stretch run caused the organization to finally confront a demon it mistakenly thought it had slayed merely through its relocation to the Vet and the transition in ownership from father to son. As such, perhaps it was Dick Allen, more than any other factor, who finally compelled the organization to modernize its approach to black athletes at last. Perhaps. One thing is for certain, however: when it comes to analyzing Dick Allen’s second act in Philadelphia, so much depends upon where one sat while taking in the performance.

MITCHELL NATHANSON is a professor of legal writing at Villanova University School of Law. He authored “The Irrelevance of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption: A Historical Review” in 2006. His books “The Fall of the 1977 Phillies: How a Baseball Team’s Collapse Sank a City’s Spirit” was published in 2008 and “A People’s History of Baseball” in 2012. His most recent article is “Who Exempted Baseball, Anyway: The Curious Development of the Antitrust Exemption That Never Was.” He is at work on a biography of Dick Allen, to be published in 2015.

Notes

1 “Tearful Dick Allen Announces Retirement,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 15, 1974.

2 Craig Wright, “Another View of Dick Allen,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 24 (1995).

3 Bruce Keidan, “Dick Allen Back in Phils Uniform?,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 13, 1974.

4 For an in-depth analysis of the relationship between the Phillies and the city of Philadelphia, see Mitchell Nathanson, The Fall of the 1977 Phillies: How A Baseball Team’s Collapse Sank a City’s Spirit, (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2008).

5 William C. Kashatus, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration, (University Park, PA: Penn State Press, 2004), 198.

6 See Frank Dolson, “Richie Allen: Phillies Could Go To Top – Or To Pieces – With Him,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 2, 1975. In the article, Dolson quotes Greg Luzinski as saying, “I think Richie Ashburn’s the guy who’s really making the push as far as whether Richie Allen comes here. His articles and his persuasion have maybe prompted the Phillies to do a little something.”

7 Allen Lewis, “Phils Secretly Trying to Lure Dick Allen Off the Farm,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 4, 1975.

8 “Richie Allen Wants to Play This Year, But Not With Braves,” Atlanta Daily World, March 28, 1975.

9 Bill Lyon, “Phils Believe They Can Win It All…With Dick Allen,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 11, 1975.

10 Frank Dolson, “Mets Tune Out Richie Allen, Fear Lack of Harmony,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 4, 1975.

11 Ibid.

12 Allen Lewis, “Montanez Ready to Vacate First for Allen,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 3, 1975.

13 Dolson, “Richie Allen: Phils Could Go to Top.”

14 Ibid.

15 Frank Dolson, “That Was a Smile On Ozark’s Face…,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 14, 1975.

16 Russ Harris, “Allen Set to Play But ‘Won’t Beg,’ ” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 26, 1975.

17 Frank Dolson, “Phils New Slogan: Give Him a Chance,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 8, 1975.

18 Frank Dolson, “The Boos Turn to Cheers for Richie Allen,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 1975.

19 Ibid.

20 Ralph Bernstein, “Bowa: Stiff Arm, Failure to Adjust to Allen Blamed for Errors of His Ways,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 5, 1975.

21 Allen Lewis, “Allen’s Future? ‘I Gotta Play,’ ” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 13, 1975.

22 Frank Dolson, “Ozark’s Composure Shatters Noisily…,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1976.

23 Ibid.

24 Allen Lewis, “Allen’s Pride is Hurt: Bats 7th,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19, 1976.

25 Allen Lewis, “Allen Clouts 2: Phils Win 12-4,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 26, 1976.

26 The events surrounding Allen during July and early August, 1976 are summarized in Bruce Keidan, “Today’s the BIG Day that Allen Comes Back,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 10, 1976.

27 Dick Allen and Tim Whitaker, Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen (New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields, 1989), 163.

28 Bruce Keidan, “Allen Declines to Join in Phils’ Fun,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 27, 1976.

29 See William C. Kashatus, “Dick Allen, The Phillies, and Racism,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 9, no. 2 (Spring 2001) 184; Tony Kornheiser, “Body and Soul,” Inside Sports, Vol.1, October, 1979, 24, 30.

30 Keidan, “Allen Declines to Join in Phils’ Fun.”

31 John Rhodes, “Dick Allen Sees Future on West Coast,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 9, 1976, 17. Rhodes wrote that he had not earlier published Allen’s remarks because Allen “warned this reporter to keep what he was going to say under his hat because of damage that might occur with management and fellow teammates.”

32 Bruce Keidan, “Phils are Resting Uneasily as Ozark Hides Hurt and Anger,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1976.

33 Bruce Keidan, “Phils Get Warning, Then Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1976.

34 Frank Dolson, “Phillies Bewildered in a Tower of Babel,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 1, 1976.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Keidan, “Phils are Resting Uneasily.”

38 Bruce Keidan, “Allen to Play, Taylor to Coach: Owner Settles Dispute,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 1, 1976.

39 See Jerome Holtzman, “Why Allen, McLain and Conigliaro Really Were Traded,” SPORT, Vol. 51, February, 1971, 38, 86.

40 Bruce Keidan, ‘They Grew Up in a Few Days,’ Ozark Declares,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1976.

41 Bill James, The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1994), 322-25.