DiMaggio’s Hitting Streak: High ‘Hit Average’ the Key

This article was written by Joe D’Aniello

This article was published in 2003 Baseball Research Journal

If it weren’t for eBay, I never would have written this article. While browsing around the mega auction site I discovered a 1995 Baseball Research Journal for sale. I entered a last-minute bid (yes, I’m one of those guys) and won the auction with a $5 bid. One article in the 1995 BRJ was titled “Streaks” by Neal Moran. Moran discussed streaks of all kinds and referred to a 1994 BRJ article by Charles Blahous titled “The DiMaggio Streak: How Big a Deal Was It?” Blahous estimated that DiMaggio had a .013% chance of hitting in 56 games or about a 1 in 750 chance.

Last year Michael Freiman (“56 Game Hitting Streaks Revisited,” 2002 BRJ) resurrected the topic and estimated that DiMaggio’s streak odds were 1 in 9,545. Moran, on the other hand, felt that it would be “more accurate [to run] a series of simulated 1941 seasons based on DiMaggio’s overall batting statistics, rerun the simulation about a zillion times and see how often a fifty-six game hitting streak [came] up.”

As a computer programmer, this challenge appealed to me. But I took the project a step further than what Moran suggested. Instead of using DiMaggio’s entire 1941 season, I wanted to put the hitting streak under a microscope. In other words, using the furious pace that produced DiMaggio’s historic streak, what kind of odds was the Hall of Famer facing — or, what were the odds of DiMaggio doing what he did when he did it?

Cup of (Mr.) Coffee

Having done past simulations (see 2000 BRJ, “The Ten Thousand Careers of Nolan Ryan”), one thing I learned was that if the sample is large enough, the results are almost predictable. That is, if the odds of something happening are 1 in 1,000, it may happen three times in 1,000 or it may happen not at all, but it won’t hap pen 95 times.

Yet there was something in the amateur mathematician in me that wanted me to at least understand why DiMaggio beat such long odds. In order to do so, I had to start simple. A hitter who hits well enough to sustain a long hitting streak would be someone who hits around .375, or three hits in eight at-bats, on average.

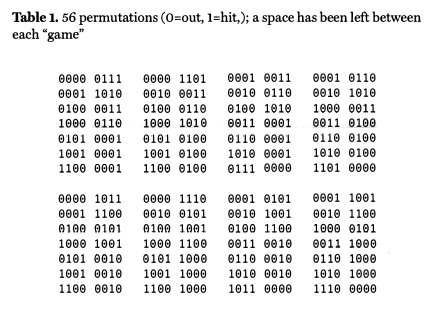

My first task was to figure out what the odds were of a player coming up from the minors for a late September cup of coffee, playing two games, getting three hits in eight at-bats, and having a two-game hitting streak. At first I thought the odds were 50-50. That is, his hit totals in the two games could be 2-1, 1-2, 3-0 or 0-3. That approach is incorrect because the distribution of 2-1, 1-2, 3-0, and 0-3 isn’t equal-there are more 2-1 or 1-2 possibilities than there are 0-3 or 3-0. It turns out there are 56 ways to get three hits in eight at-bats with four at-bats per game. Table 1 shows the 56 permutations:

For example, in the left uppermost cell, the hitter batted four times in the first game and failed to get a hit (0000). In the second game he went three-for-four, getting hits in his last three at-bats (0111). Of those 56 combinations only eight fail to secure a two-game hitting streak, the first four and the last four. The number of permutations, p, is determined by the following equation:

Where pa is plate appearances, h is hits and -h is the number of non-hit plate appearances (pa – h). In other words p = (1 X 2 X 3 X 4 X 5 X 6 X 7 X 8) + ((1 X 2 X 3) X (1 X 2 X 3 X 4 X 5)) or in real numbers p = 40320 + (6 X 120) = 56.

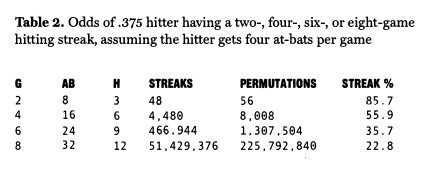

That means that Joe Cupacoffee has a 48/56 (85.7%) chance of having a two-game hitting streak, much better than the 50% I originally thought. But as Mr. Cupacoffee’s games increase linearly, p increases exponentially. My computer could handle only up to an eight-game hitting streak, which took two hours to run and had 225 million permutations. I estimated that a 12-game hitting streak ( 40 billion permutations) would take my computer a couple of days and a 14-game hitting streak (7 trillion) about seven years.

Obviously, the more games played, the more difficult it is to maintain a hitting streak. Basically, each additional two games played had roughly two-thirds the chance of its predecessor of being successful (i.e., 55.9 + 85.7 = .65). Blahaus noted in his article that each game plate appearance above and beyond four added little to the odds of getting a hit in that game, but reducing the number of plate appearances significantly impacted the odds. If Mr. Cupacoffee’s at-bat/game split is changed from 4+4 to 3+5, his odds of reaching a two-game hitting streak slip from 85.7% to 80.4% (45/56). With a 2+6 split, his odds of success see a steeper slide to 71.4% ( 40/56).

Oh! Those Base on Balls

It has been argued that DiMaggio’s temperament factored into the hitting streak equation. That may be so, but his batting habits had more of an impact. The man knew he was the big gun in the Yankee lineup, and he wanted to swing the bat, figuring he had a better chance for a hit than the hitters behind him in the lineup. This logic may go against current wisdom that hails high on-base percentages, but it is essential for maintaining a long hitting streak. During his streak, DiMaggio walked only 21 times and was hit by a pitch twice. That’s just 23 plate appearances that DiMaggio “wasted” in his batting streak.

When a hitting streak is in progress there are only two results: a hit or a non hit. Outs, errors, sacrifice flies, walks, hits by pitcher . . . all of them do nothing to forward a hitting streak. True, if the hitter has all his plate appearances in a game result in walks, hit by pitches, sacrifices (not sacrifice flies), or reaching first on catcher’s interference, the game will be excluded from the hitting streak, and the streak will continue.

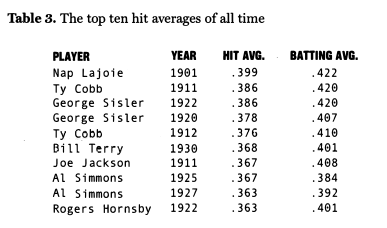

DiMaggio, however, didn’t have the luxury of such a ruling, and in general, a walk is as much an anathema to a hitting streak as a no-decision is to a pitcher trying to win twenty games. Throughout the streak, DiMaggio batted .408 (91 for 223), but his hit average (Hits + Plate Appearances) was .370. How great is a hit average of.370? Had DiMaggio been able to keep up that pace all season, his hit average would have been the sixth-highest ever. The top ten list below should offer no surprises:

For the 1941 season, DiMaggio’s hit average of .311 was his fourth best behind 1939 (.340, 64th best in history), 1940 (.313) and 1937 (.312). The top mark of the new millennium is Nomar Garciaparra’s .333 (98th best) in 2000. The only player to top .350 since 1930 is Tony Gwynn with .352 (26th best) during the strike-shortened 1994 season.

The Simulation

Based on plate appearances in each game, I simulated DiMaggio’s hitting streak exactly as it occurred in 1941. DiMaggio had three games with just three plate appearances and in game 49, a five-inning rain-shortened game, had just two plate appearances. Joltin’ Joe’s 91 hits during the streak were randomly sprinkled throughout his 246 plate appearances.

After one million simulations DiMaggio had 155,536 occurrences where he failed to get a hit in the first game (1 in 6 chance). He had a 54% chance of having a four-game hitting streak, and this matches up well with Joe Cupacoffee’s chances as listed in Table 2. DiMaggio had a 1 in 126 chance of reaching the halfway mark (28 games).

As for going all the way, it happened 15 times in my one million simulations, giving DiMaggio a 1 in 66,667 chance of success. If you think a sample of one million isn’t large enough, I ran the program another one million times. In the second million, DiMaggio had sixteen 56-game hitting streaks.

If DiMaggio were able to keep up his .370 hit average over an entire season — and that’s asking a lot — he would have a 1 in 673 chance of getting a 56-game hitting streak in 1941. The number 673 is derived by dividing his odds (66,667) by the 99 opportunities for getting a 56-game hitting streak in a 154-game season.

What About Ted Williams?

Interestingly, Ted Williams began a 23-game hitting streak the same day DiMaggio started his record streak. Williams not only batted .406 in 1941, but he outhit DiMaggio .412 to .408 during the 56-game streak. Nevertheless, Williams’ penchant for walking made it virtually impossible for him to sustain a long hitting streak. Williams walked 147 times and was hit by three pitches in 1941.

When factored to the same amount of plate appearances that DiMaggio had during his hitting streak (236), Williams would have sacrificed more than twice as many plate appearances over 56 games, costing him 15 hits. The Splinter’s hit average of .305 – the best of his career – was far below DiMaggio’s .370.

I modified the program to simulate Ted William’s chances of getting a 56-game hitting streak based on his 1941 statistics (factored down to 56 games), and it wasn’t even close. In one million simulations, DiMaggio had 883 hitting streaks of at least 40 games in duration; Williams had nine, with a 43-game streak being the longest. Given that DiMaggio’s 1941 hit-average of .311 wasn’t much higher than Williams’ only heightens the magnitude of his accomplishment.

The Future

There are some records that will never be broken, like Owen Wilson’s 36 triples or Walter Johnson’s 113 shutouts. But most of those records are due to a game that has changed. It’s unlikely that any pitcher starting his career today will have 113 complete games, let alone that many shutouts.

But every day there are hundreds of hitting streaks in progress. In one month a hitter can go from no hitting streak at all to past the halfway mark of the Clipper’s streak, yet in 62 years nobody has seriously challenged this magnificent accomplishment and only Pete Rose has managed to get even 75% toward the goal.

But with odds of 1 out of 66,667 for a .408 hitter hit average .370-it might be wiser to put your money on 37 triples.

JOE D’ANIELLO lives in Niskayuna, New York, with his wife and two children. He met Joe DiMaggio at a baseball card show in 1986, and Joltin’ Joe graciously posed for a picture with the author’s father.

Sources

Blauhous, Charles. ‘The DiMaggio Streak: How Big a Deal Was It?” Baseball Research Journal, No. 23. Society for American Baseball Research, 1994.

Freiman, Michael. “56-Game Hitting Streaks Revisited,” Baseball Research Journal, No. 31, pp. 11-15. Society for American Baseball Research, 2002.

Moran, Neal. “Streaks: Statistics vs. Serendipity,” Baseball Research Journal, No. 24, pp. 79-80. Society for American Baseball Research, 1995.

Neft, David S., Richard M. Cohen, Michael L. Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball. New York: Griffin Trade Paper, 2000.

Seidel, Michael. Streak: Joe DiMaggio, and the Summer of’41. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.