Disposable Heroes: Returning World War II Veteran Al Niemiec Takes on Organized Baseball

This article was written by Jeff Obermeyer

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

This article was selected as a winner of the 2010 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

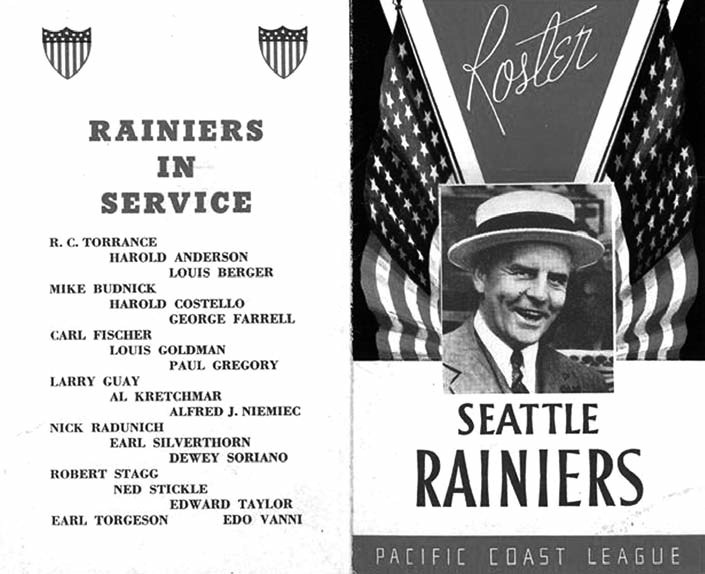

Al Niemiec looked forward to returning to baseball after his discharge from the U.S. Navy in January 1946. In the three seasons, 1940–42, before his call to duty, he played for a Seattle Rainiers team that won three consecutive Pacific Coast League championships, and he led second basemen in fielding percentage all three of those years. But things didn’t feel quite right to Niemiec. During a train ride north from California these several years later, he confided in fellow veteran Tony Lupien his fears that the Rainiers planned on releasing him soon because of his age. Lupien had a similar experience on his return from duty when the Phillies sold his contract to the Hollywood Stars. Lupien initially fought the move under the provisions of the Selective Training and Services Act of 1940 that guaranteed returning vets one year of employment in their old jobs, but he dropped the case when Hollywood agreed to pay him $8,000 for the season—the same amount he would have received had he remained in Philadelphia.1

Al Niemiec looked forward to returning to baseball after his discharge from the U.S. Navy in January 1946. In the three seasons, 1940–42, before his call to duty, he played for a Seattle Rainiers team that won three consecutive Pacific Coast League championships, and he led second basemen in fielding percentage all three of those years. But things didn’t feel quite right to Niemiec. During a train ride north from California these several years later, he confided in fellow veteran Tony Lupien his fears that the Rainiers planned on releasing him soon because of his age. Lupien had a similar experience on his return from duty when the Phillies sold his contract to the Hollywood Stars. Lupien initially fought the move under the provisions of the Selective Training and Services Act of 1940 that guaranteed returning vets one year of employment in their old jobs, but he dropped the case when Hollywood agreed to pay him $8,000 for the season—the same amount he would have received had he remained in Philadelphia.1

Organized Baseball developed its own rules regarding returning vets, specifically that they were entitled to their old jobs for a trial period of 15 days of regular-season play or 30 days of spring training, after which the club could terminate the contract at its discretion. The motivating factor was obviously one of money, though the potential for bad publicity should have been apparent from the start. Baseball rode a wave of patriotism as the “American game” during the Second World War and took steps to promote the game as such. By 1945 major-league attendance had rebounded from the slump it endured early in the war, jumping to approximately 10.8 million, a new record, along with record gross receipts of $22.5 million. The majors shattered this record the next year, 1946, drawing more than 18 million fans through the turnstiles and grossing $51.7 million.2 It was a time of record popularity and profits, and not a time to take an unpopular stance with respect to veterans, who made up a significant portion of the game’s fan base.

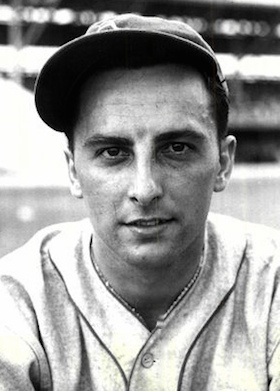

Alfred Joseph Niemiec was born in Meriden, Connecticut, on May 18, 1911. He attended and played baseball for the College of the Holy Cross from 1931 through 1933 before making his way to the minors, finishing out the 1933 season with the Reading Red Sox of the New York–Pennsylvania League. His solid infield play and .306 average won him recognition, and in 1934 he played in 137 games with Kansas City in the American Association. His efforts in Kansas City earned him a late-season call-up with the Boston Red Sox, and he made his major-league debut on September 19, picking up two hits and one RBI against the St. Louis Browns. While his fielding was perfect in nine games with Boston, his bat was weak (.219), and Niemiec found himself assigned to Syracuse for the 1935 season, where he contributed to the Chiefs’ International League championship. Once again his play attracted the attention of the majors, and the Philadelphia Athletics sent Doc Cramer and Eric McNair to Boston in exchange for Niemiec, Hank Johnson, and, perhaps just as important for Connie Mack, $75,000 in cash. Niemiec spent the entire 1936 season on the Athletics’ roster, appearing in 69 games and splitting time between second base and shortstop, but once again major-league pitching confounded him, and his .197 average prompted his sale to the minors in the offseason.

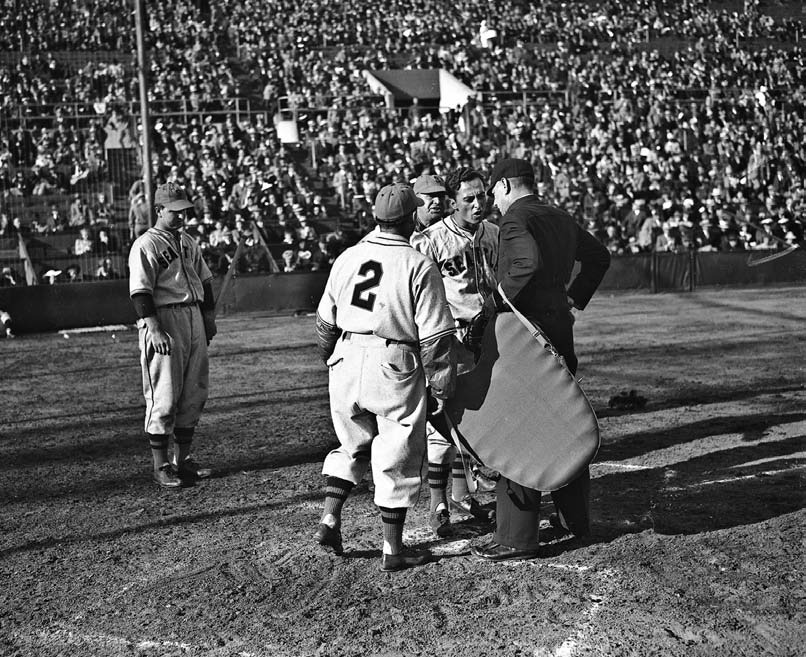

Al Niemiec has a word with the umpire in 1940. From left: Seattle Rainiers outfielder Frank Kelleher, coach Eddie Taylor, manager Jack Lelivet and Niemiec. (David Eskenazi Collection)

Following a year with Little Rock, where he won a championship with the Travelers, Niemiec made his way out west for a five-year stint in the PCL. He spent two seasons with San Diego before moving north to Seattle to play for the Rainiers in 1940. Anchoring the keystone sack for the Rainiers, Niemiec, an outstanding defender, also maintained a respectable .278 average during the Rainiers’ run of three consecutive PCL titles. After the close of the 1942 season he was called up to serve in the U.S. Navy, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant before his honorable discharge on January 6, 1946.

On his discharge, Niemiec reclaimed his former job with the Rainiers, and on February 11 the club signed him to a contract at $720 per month, a fairly substantial increase from the $575 per month he earned in 1942. He appeared in 11 games at the start of the 1946 season but was beaten out for the job at second by Bob Gorbould, who played for the Rainiers in 1944 and 1945 and was seven years his junior.3 The Rainiers cut Niemiec on April 21, and he went immediately to the local Selective Service office to register a complaint against the club, based on the job guarantees to returning veterans under the Selective Training and Services Act. He brought with him a letter of introduction provided to him by the team on his dismissal, which was signed by manager Bill Skiff and vice president Roscoe “Torchy” Torrance:

April 20, 1946

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

This will introduce player Al Niemiec. Al played on the Seattle Ball Club during three championship years, 1939 [sic], 40, and 41. We won the pennant all three years. He was chosen the outstanding second baseman of the league in 1941 and is one of the most dependable ball players we have ever had the privilege of having in the organization.

Al has just returned from more than three years in the United States Navy and returned to our roster this year. The surplus of talent and the fact that we have had to make room for some younger ball players has made it necessary for us to dispose of Mr. Niemiec’s services. Al still has a lot of fine baseball left we are sure and is the type who would be a credit to the game in years to come as a manager of some club. The loyalty and integrity of this ball player has always been away above average and we would not hesitate a moment in recommending his services to anyone in the baseball business.4

The Selective Service System wasted no time in arguing Niemiec’s case, sending a letter to club president Emil Sick on April 24. In the two-page letter Lt. B. V. Vercuscki outlined the facts, including the team’s obligations under the Selective Training and Service Act. Vercuski wrote that Niemiec’s dismissal was “without cause” and that he was still capable of playing baseball at an acceptable level: “There is nothing in the record to reflect that he does not have the ability or background to continue in his former position.”5 The severity of the situation was readily apparent to the Rainiers, and Torrance dispatched copies to the heads of the PCL (Clarence Rowland), the National Association (W. G. Bramham), and Major League Baseball (commissioner Happy Chandler). Torrance even offered a possible compromise to the situation: “Just as an after-thought don’t you think it would be a good idea to let the Mexican League have about 200 ball players so that they could set up a real baseball program and take care of some of our surplus talent? It might be better to have a good league down there and make more room for extra ball players than to continue having trouble.”6

The Rainiers retained attorney Stephen Chadwick of the firm Chadwick, Chadwick and Mills to meet with the government officials, who on May 6 followed up with another letter from the U.S. district attorney demanding Niemiec’s reinstatement. Chadwick and the Rainiers held fast to their position:

We replied by letter dated May 9, but delivered May 13, declined to reemploy upon the ground that we had reemployed, he had been accorded the time prescribed as a reasonable minimum by National Association rules, and had demonstrated his inability to comply with the accepted standards of work performance and professional skill and proficiency required of our players and by clubs with which we were in competition, and accordingly had been given his unconditional release and had accepted transportation to his home.7

The Rainiers did not stand alone, having the full support of Organized Baseball. The impact of any court ruling on the Niemiec case had far-reaching consequences, and it was deemed so important that Major League Baseball and the National Association agreed to split the cost of the legal expenses involved in defending the case.

It is ironic that Stephen Chadwick represented the Rainiers and baseball against Niemiec. Chadwick too was a veteran, who served in the Russian Civil War, one of the little-known conflicts related to the First World War. While the Bolshevik rise to power in the 1917 Revolution is well known, what is often neglected by popular history is the attempt by the anti-Bolshevik “White” forces to overthrow the new communist government. A number of foreign powers participated on both sides of this conflict, and Chadwick served with U.S. forces in support of the Whites from August 1918 to May 1919. Chadwick was also heavily involved in leadership roles in various veterans’-rights organizations; he served as the National Commander of the American Legion in 1938–39. While Chadwick’s firm represented Emil Sick’s business ventures, both baseball and brewing, his willingness to argue against the legal rights of returning veterans is surprising given his background.

As the legal wrangling continued, Niemiec signed with Providence of the New England League on May 17 for $150 a month. Back in Seattle the two sides prepared to take the case in front of federal judge Lloyd L. Black on June 15. Further complicating matters for the Rainiers was that they fired manager Bill Skiff on June 11, though they still needed him to testify on their behalf at the hearing. Skiff toed the company line, however, and testified that Niemiec was too old and slow to play in the PCL. Niemiec’s representatives pounced on the former manager, attempting both to impeach his judgment in baseball matters, by raising his recent termination, and to show that Skiff himself had still been an active player when he was older than Niemiec. Niemiec returned to Seattle from Providence to participate and testify on his own behalf.8

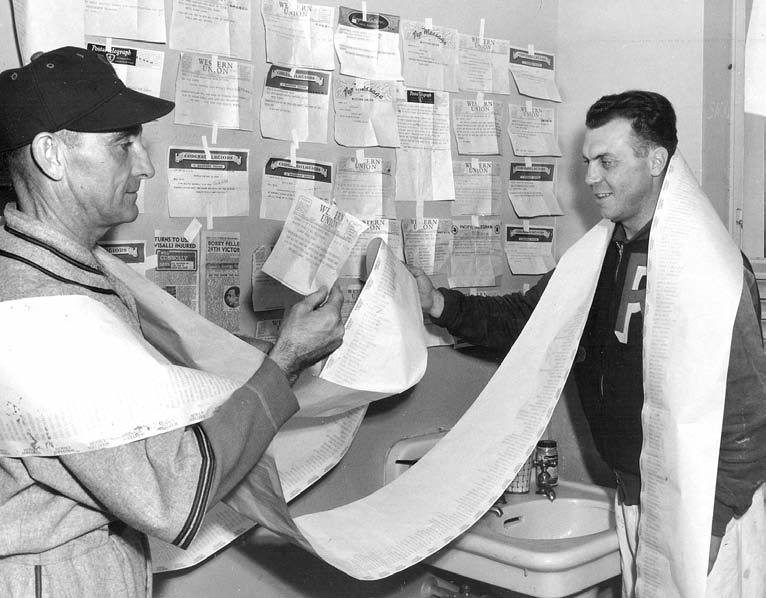

Rainiers manager Jack Lelivet (left), with team trainer Lewis “Doc” Richards in 1941, testified on behalf of the Rainiers, affirming their claim that Al Niemiec was too old to play second base effectively. (David Eskenazi Collection)

Judge Black announced his decision in favor of Niemiec on Friday, June 21, and brought the parties back to the courtroom on June 24 to elaborate on his ruling. Black specifically addressed three arguments made by the Rainiers—that baseball is “a quasi public institution not operated primarily for profit,”9 that Niemiec’s skills had eroded and he was no longer capable of playing at an acceptable level, and that by signing a contract that gave the club the right to cut him Niemiec waived his rights under the Selective Training and Service Act.

In addressing the first issue, Judge Black reviewed the articles of incorporation of the Pacific Coast League and stated that these clearly indicated the league was a for-profit enterprise. He added that the Selective Training and Service Act made no concessions for not-for-profit organizations or for any other type of employer. As for Niemiec’s skill and ability to perform the job of baseball player:

The law says [Niemiec] is entitled to his position for a year. The veteran must be qualified to perform the duties of his position.

The evidence shows he was. The employer may adopt fair and reasonable standards of qualification for work performance. Under the evidence there was no qualification or standard at all. In substance the most Mr. Skiff said was that he had the idea that Mr. Niemiec would not be able to complete the season. He had no right to anticipate Mr. Niemiec’s inability until it occurred. The employer may discharge at any time for cause, but that cause must be something other than prediction or [the] hunch of a manager.10

The contract issue was dealt with clearly as a matter of contract law. The employer in this case wrote the contract, and the employee was not allowed any input or modification—he had to take it or leave it as written. In fact, the evidence presented indicated that the management of the Rainiers, as officers of a member club of the National Association, could no more modify the contract than could Niemiec. As the employer had complete control over the wording of the contract, it had a duty to write the contract in clear and unambiguous language, which, according to Judge Black, it did not. “Any player reading this contract, I am satisfied, would believe his rights were protected. Personally, after I have read it, I think his rights are protected.”11

Judge Black reserved his more pointed criticism for the behavior of the game as a whole toward its returning veterans:

Baseball is an American institution. Professional baseball is a great American institution. Compared with many professional sports and entertainments it holds a very high regard of the people of the nation. I cannot escape the view, however, that the argument of the respondent analyzed completely means just this, that if the baseball player be older when he comes back from service than when he entered it, his baseball club employer is given the right in its discretion to repeal the Act of Congress.12

Black then took this a step further, to recognize the contributions veterans had made to protecting American society: I recognize the seriousness to baseball of having the judge dictate as to its players. But since it has been argued—and correctly—that baseball is the American game, certainly, then baseball ought to bear its share of any burden in being fair to service men. There are few institutions in American life which ought to feel a greater obligation. If Mr. Niemiec and all the others had failed in their job, there would be no American manager of any baseball if such should be played at the stadium this year. If the Nazis permitted baseball, it would not be an exhibition that any of us liked.13

Though Black ruled in Niemiec’s favor, he was clear that his ruling did not require the Rainiers to actually play him. In fact, so long as the Rainiers paid him a full season’s salary, minus any earnings he made in any other occupation (including non-baseball occupations), the club had no other responsibilities. The ruling satisfied Niemiec, who sent word to Providence that he was not returning, and on July 1 he began a new job as a beer salesman—ironically, working for the brewery owned by Rainiers president Emil Sick. Niemiec returned to baseball briefly as general manager for the Great Falls Electrics (a Rainiers farm team) of the Pioneer League in 1948 before leaving the game for good. He later became a golf pro and instructor.

The ruling did not sit well with baseball’s executives. Happy Chandler sent a telegram to the club about appealing the decision. “The Niemiec case should be appealed through the higher courts. Organized baseball will help bear the expense of the appeal.”14 Chandler attended a special meeting of the board of directors called by the PCL on July 22–23. There the parties agreed to pursue an appeal, with the expenses underwritten by the major leagues and the National Association—an agreement that applied not only to the Niemiec case but to any others that arose.

Per the meeting minutes:

Following discussion of the Al Niemiec case, Director Starr moved that the Pacific Coast League concur in the arrangement whereby the Major Leagues and the National Association will take care of half of the survey and further legal involvement in the Niemiec case as well as any other National Defense Player situation that may arise. Duly seconded, and carried unanimously.15

The potential ramifications were significant— The Sporting News estimated that the ruling might impact as many as 143 former major leaguers, plus another 900 players at the triple-A level, and even more at the lower levels. However, players had to file a complaint in order to pursue their benefits. Some decided it wasn’t worth the trouble, while others encountered roadblocks; Bob Harris, for example, was pressured by his local district attorney to amicably settle his case against the Philadelphia Athletics.16

Discussion regarding a possible appeal of Judge Black’s ruling continued through the summer, but at the close of the PCL season the Rainiers were ready to step aside. A judgment in the amount of $2,884.50 (unpaid contract value of $3,552.00, minus $75.00 Niemiec earned playing for Providence, and minus $592.50 he earned as a salesman) was entered against the Rainiers on September 18, and they were prepared to pay. By October, correspondence between the Rainiers and baseball officials was focused on determining the costs owed by each party, with no further talk of appeals. By that time the major leagues and National Association understood how profitable the 1946 season had been and were ready to put this issue behind them. The Rainiers finally satisfied the judgment on November 1 with a payment of $2,905.36 (including post-judgment interest), though the satisfaction of judgment was not filed with the court until December 21, a time specifically chosen to fall after the winter baseball meetings so as to reduce the likelihood of questions from the press.17

In the end, the Niemiec case cost the major leagues and the National Association $1,718.28 each in legal expenses, and the Rainiers incurred the cost of the judgment. At least two other Rainier players received similar payments as a result of Judge Black’s ruling— John Yelovic ($1,000.00) and Larry Guay ($1,100.00).18 Not all vets were as fortunate. Some, like Steve Sundra of the St. Louis Browns, lost their court cases.19

However, the Niemiec ruling remained pivotal and contributed to a number of veterans receiving the pay they were owed by baseball under the Selective Training and Services Act of 1940. The case is touched on in writings about baseball during the Second World War as well as in writings about the game’s labor issues, but what the documentary evidence shows is the previously unreported direct involvement of both Major League Baseball and the National Association in this dispute involving a minor leaguer. The willingness of these two organizations to pay the legal costs, as well as the obvious potential for negative publicity, illuminate what an important issue this was in the eyes of baseball owners and executives, in terms of profits but perhaps even more so in maintaining complete control over the players. The players who served in the Second World War did so fighting for a democratic society, but they returned to a game in which the owners held the power and the players had no say in their own careers, a status quo that remained in place for another twenty years until the rise of the Major League Baseball Players Association. Still, the Niemiec decision was one small step forward in favor of players’ rights, earned by one veteran who took on baseball and fought for what was right.

JEFF OBERMEYER earned a master’s degree in military history from Norwich University in 2009, where he wrote on the relationship between Major League Baseball and the military during the Second World War. In the offseason he researches the history of hockey in his hometown of Seattle.

The Niemiec case contributed to a positive outcome for a number of veterans who sought the pay they were owed by baseball under the Selective Training and Services Act of 1940. (David Eskenazi Collection)

Notes

1 Lee Lowenfish and Tony Lupien, The Imperfect Diamond: The Story of Baseball’s Reserve System and the Men Who Fought to Change It (New York: Stein and Day, 1980), 129–34. Niemiec filed away Lupien’s story in his memory in case he needed it.

2 House Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Organized Baseball, 82d Cong., 2d sess., 1952, report no. 2002, 90 Stephen Chadwick, 94.

3 The SABR Encyclopedia and the Social Security Death Index give Gorbould’s date of birth as November 19, 1918. However, in The Coast League Cyclopedia: An Encyclopedia of the Old Pacific Coast League, 1903–1957, vol. 1, Batters A through K (Baseball Press Books, 2003), Carlos Bauer gives his date of birth as November 19, 1920.

4 Letter to Al Niemiec, April 20, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

5 Lt. B. V. Vercuski to Emil Sick letter, April 24, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

6 R. C. Torrance to A. B. “Happy” Chandler, letter, April 27, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

7 Stephen Chadwick, to Victor Ford Collins, letter, May 17, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

8 Royal Brougham, “Niemiec Hearing Closes, Judge Takes Case under Advisement,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1946, 10.

9 Niemiec v. Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., 67 F. Supp. 705 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1946), 2.

10 Niemiec v. Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., 67 F. Supp. 705 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1946), 6.

11 Niemiec v. Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., 67 F. Supp. 705 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1946), 4.

12 Niemiec v. Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., 67 F. Supp. 705 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1946), 2.

13 Niemiec v. Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., 67 F. Supp. 705 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1946), 6.

14 Albert B. Chandler to Roscoe Torrance, Western Union telegram, June 25, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

15 Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Board of Directors of the Pacific Coast Baseball League, July 22 and 22 [sic], 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

16 Lowenfish and Lupien, 137.

17 S. F. Chadwick to Joseph C. Hostetler letter, November 7, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

18 Notes from special meeting, board of directors, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., November 25, 1946, Seattle Rainier Baseball Club Records Collection, Washington State Historical Society.

19 Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan, 1980), 273.